The development of Indian civilization

The development of Indian civilization is a cornerstone in the history of human culture. Emerging in the fertile plains of the Indus and Ganges rivers, it laid the groundwork for some of the most profound cultural, religious, and intellectual advancements in human history. Like Mesopotamia and Egypt, whose civilizations also arose along fertile river systems such as the Tigris, Euphrates, and Nile, and like China, rooted in the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, Indian civilization demonstrates how geography shaped early societies. Indian civilization, dating back to around 3300 BCE with the Indus Valley Civilization, evolved uniquely while interacting with neighboring cultures and adapting to dynamic historical contexts. Its trajectory reflects a balance of continuity and change, influenced by geography, migration, and innovation.

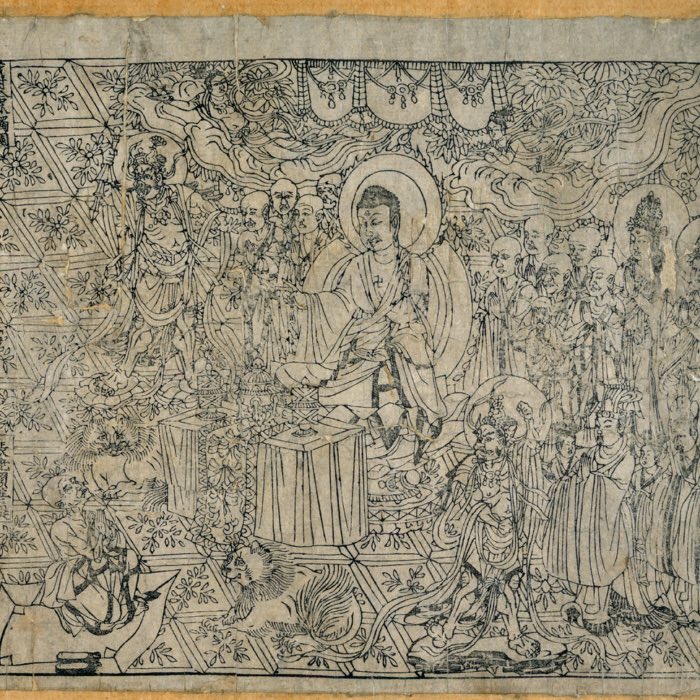

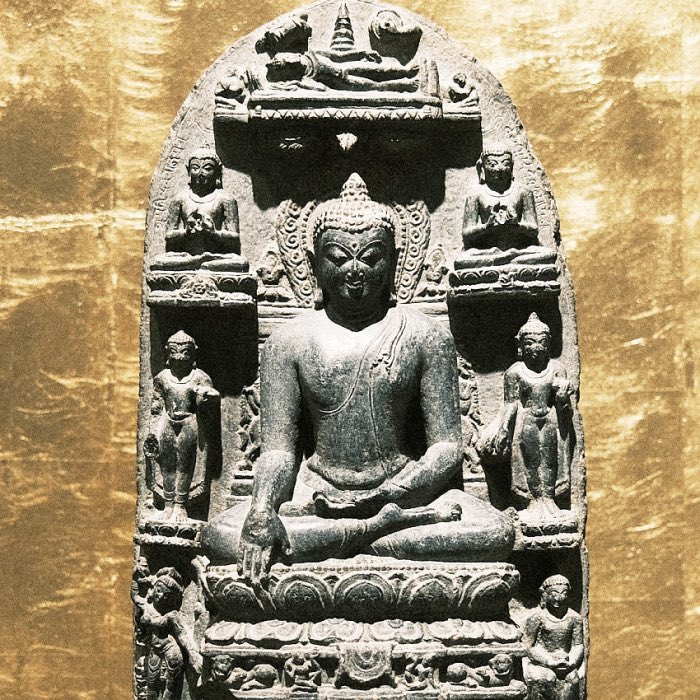

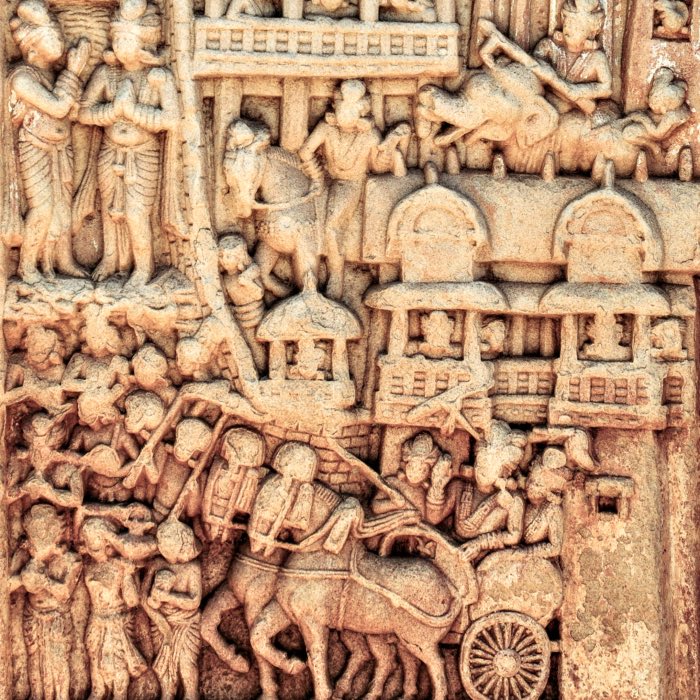

Buddhist “Chaitya Griha” or prayer hall, with a seated Buddha, Cave 26 of the Ajanta Caves. Caves like these, adorned with intricate sculptures and paintings, are a testament to the artistic and religious achievements of Indian civilization. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Geographical foundations of Indian civilization

The Indian subcontinent’s diverse geography has been instrumental in shaping its civilization. The fertile floodplains of the Indus and Ganges rivers supported the growth of early agricultural societies. The Indus River, in particular, facilitated the rise of one of the world’s earliest urban cultures — the Indus Valley Civilization. In contrast, the Ganges plains became a cradle for the later Vedic and subsequent Indian empires.

Extension of the Indus Valley Civilization at peak, c. 2600-1900 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

India’s natural barriers, such as the Himalayas in the north and the Indian Ocean to the south, provided protection while enabling controlled interactions through passes like the Khyber. This duality of isolation and connectivity allowed for unique cultural development while also absorbing influences from Central Asia, Persia, and beyond.

Indus Valley Civilization: Urban pioneers

The Indus Valley Civilization (ca. 3300–1700 BCE) represents one of the earliest instances of urban planning and social organization. Centers like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa were characterized by grid-like city layouts, sophisticated drainage systems, and standardized weights and measures. Archaeological evidence suggests a thriving economy based on agriculture, trade, and craft specialization.

Left: Mohenjo-daro, one of the largest Indus cities. View of the site’s Great Bath, showing the surrounding urban layout. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Archaeological remains of washroom drainage system at Lothal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

View of Granary and Great Hall in Harappa, an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, part of the Indus Valley Civilization. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: Ceremonial vessel; 2600–2450 BC; terracotta with black paint. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Priest-King; 2400–1900 BC; low fired steatite. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

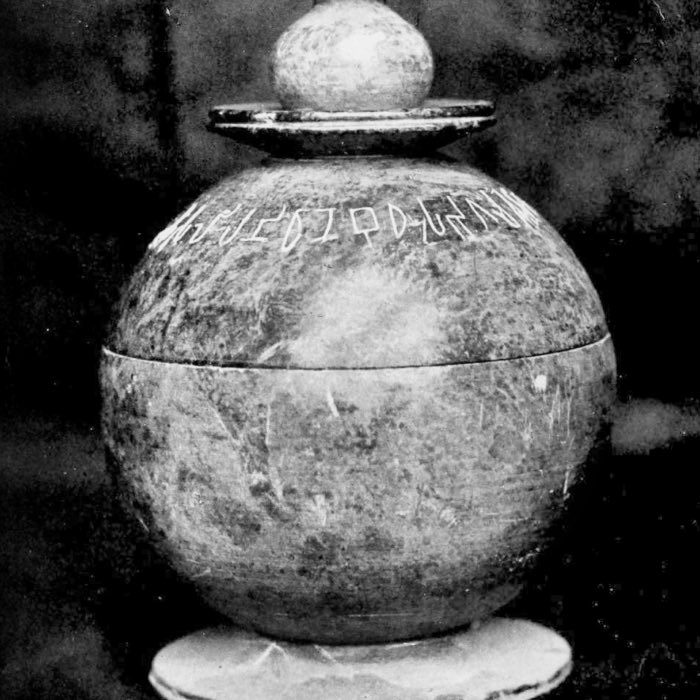

Example of the Indus script: Stamp seal and modern impression: unicorn and incense burner (?); 2600–1900 BC; burnt steatite. The Indus script, still undeciphered, is found on seals, tablets, and pottery and is credited with being one of the world’s oldest writing systems. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Although much about the Indus Valley Civilization’s religion remains speculative due to the undeciphered nature of its script, archaeological evidence points to a rich spiritual tradition. Artifacts such as the “proto-Shiva” seal, depicting a horned figure surrounded by animals, suggest early forms of ritual practice and possibly proto-Hindu elements, such as reverence for fertility and nature. Other motifs, such as the pipal tree and ritual bathing tanks, are thought to prefigure later Indian religious practices.

The Pashupati seal, or Proto-Shiva seal, showing a seated and possibly tricephalic figure, surrounded by animals; circa 2350–2000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Despite the lack of deciphered writing, the material culture of the Indus Valley hints at a complex society with social hierarchies, trade networks extending to Mesopotamia, and religious practices centered around fertility symbols and sacred animals. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilization around 1700 BCE remains a topic of debate, often attributed to environmental changes, such as shifts in the course of rivers or climatic fluctuations.

Historical developments from the Indus Valley Civilization to modern India

The Vedic Age: Foundations of Indian culture

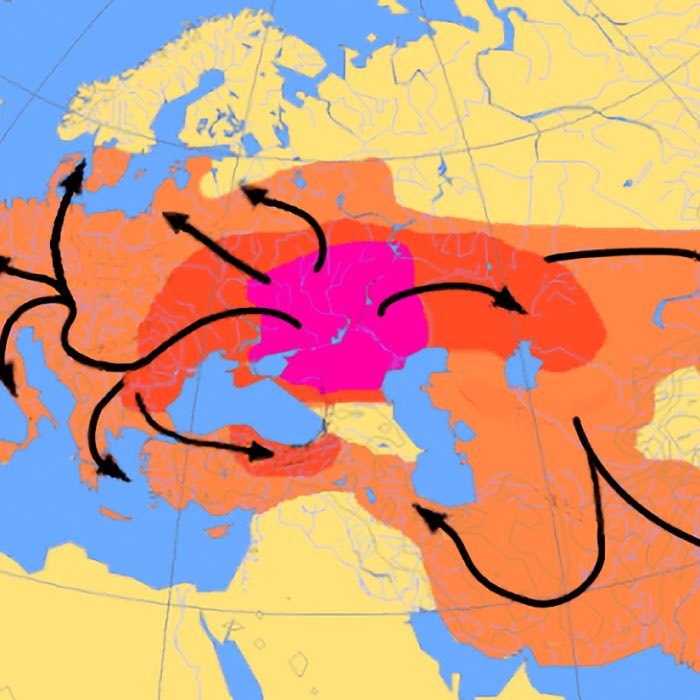

Following the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, the Vedic Age (ca. 1500–600 BCE) marked a significant cultural transformation. This period is named after the Vedas, a collection of sacred texts composed in Sanskrit. The Indo-Aryans, who are believed to have migrated into the subcontinent during this time, brought with them new cultural elements, including the Sanskrit language, chariot warfare, and a pantheon of deities.

Late Vedic culture (1100-500 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The society of the Vedic Age initially revolved around semi-nomadic pastoralism but gradually transitioned to settled agriculture. This period saw the emergence of the varna system, which would later evolve into the caste system, as well as the early foundations of Hinduism. The later Vedic period also witnessed the rise of kingdoms (janapadas) and the consolidation of political structures, laying the groundwork for the first Indian empires.

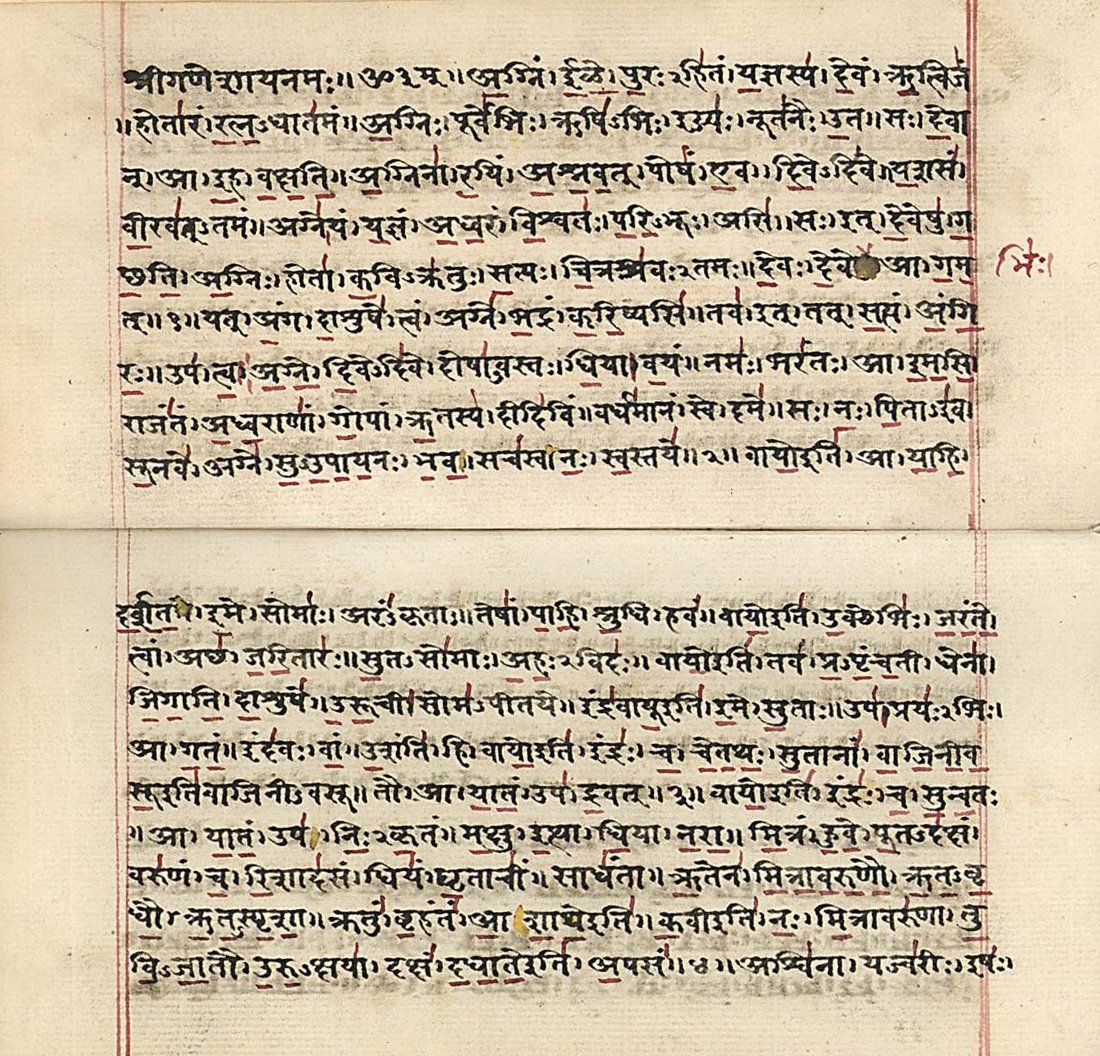

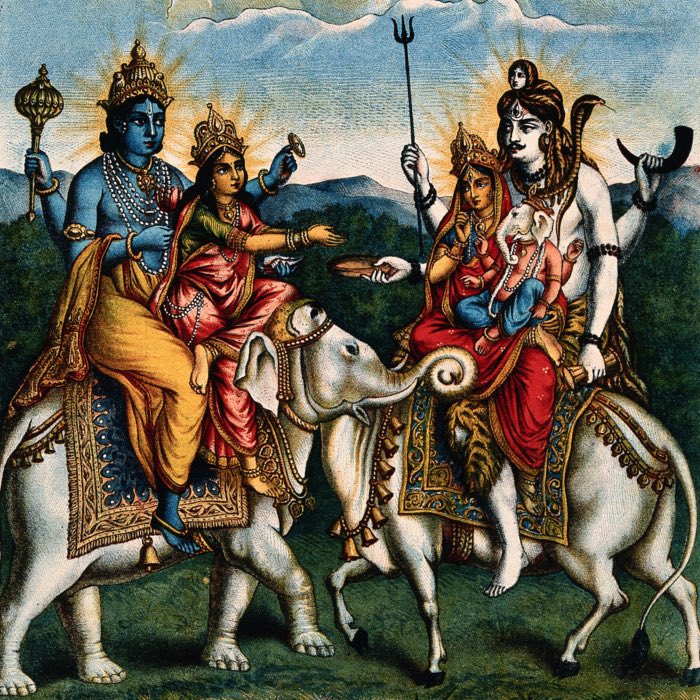

The Vedic culture was characterized by a rich oral tradition, with hymns, rituals, and philosophical speculations transmitted through generations of priests and scholars. The Vedas, composed in different periods, reflect the evolving religious and social norms of ancient India. The Rigveda, the oldest of the four Vedic Samhitas, reflects a religion centered on nature worship, ritual sacrifice (yajna), and the invocation of deities (devas). The pantheon included gods such as Agni (fire), Indra (war and rain), Varuna (cosmic order), and Soma (ritual intoxication and ecstasy). These deities represented natural forces and abstract principles, and their worship was mediated by priestly rituals performed to sustain cosmic balance (rita).

The Vedic period also saw the emergence of philosophical speculation. Concepts such as brahman (the ultimate reality) and ātman (the self or soul) began to appear in later texts, particularly in the Upanishads. These developments represented a shift from external rituals to internalized spirituality, focusing on the relationship between the individual and the cosmos.

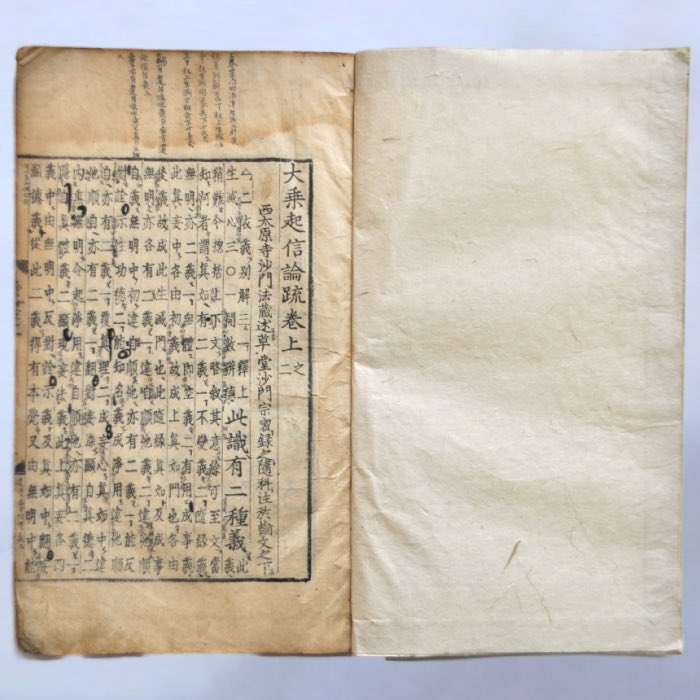

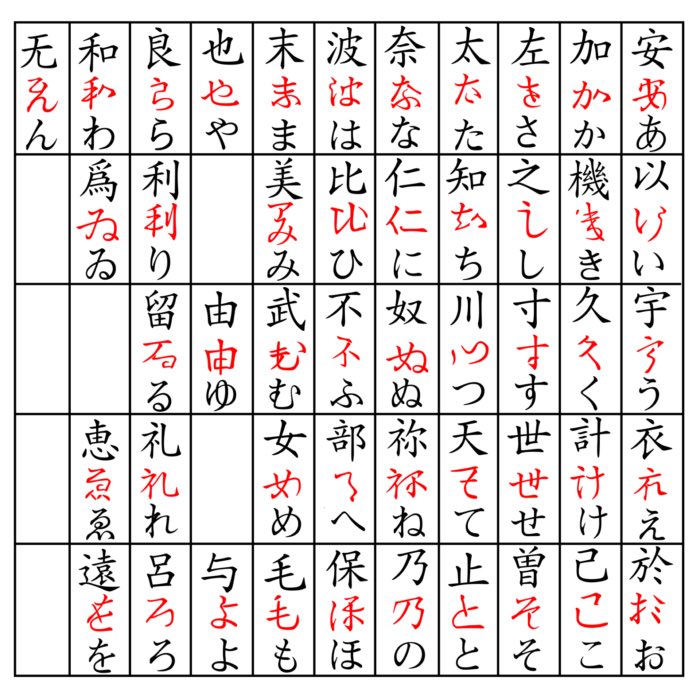

An early-19th-century manuscript of Rigveda (the Rigveda is one of the four Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism). The text is written in Sanskrit (Devanagari script) and is a hymn dedicated to Agni (fire god). The text is in the form of a padapatha (word by word), with the Vedic accent being marked by underscores and vertical overscores in red. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Rise of empires: Political unity and cultural flourishing

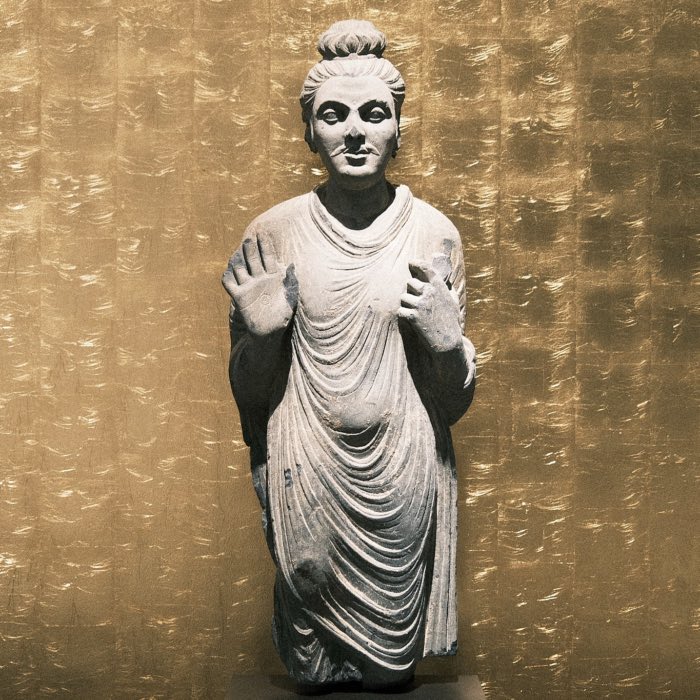

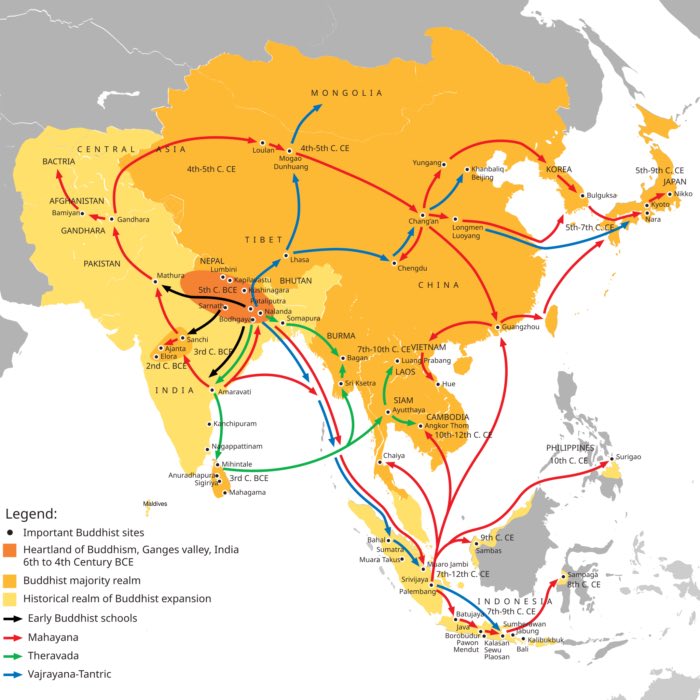

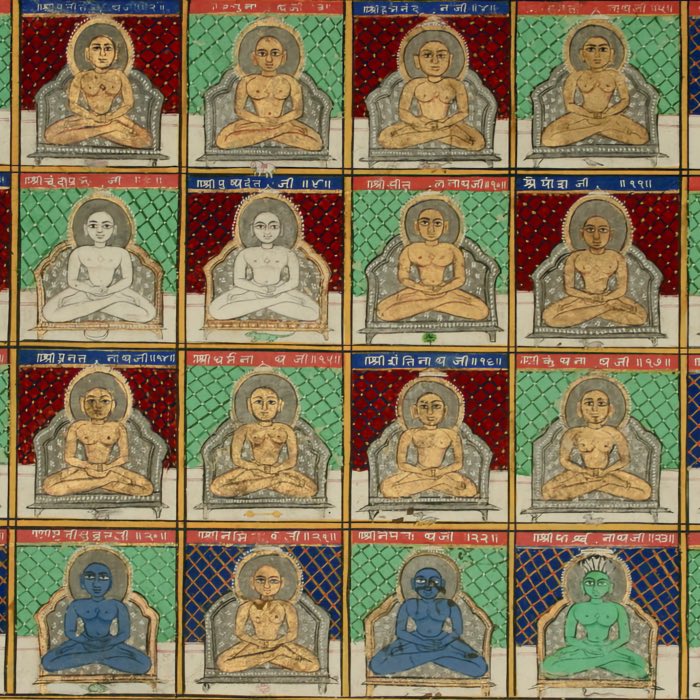

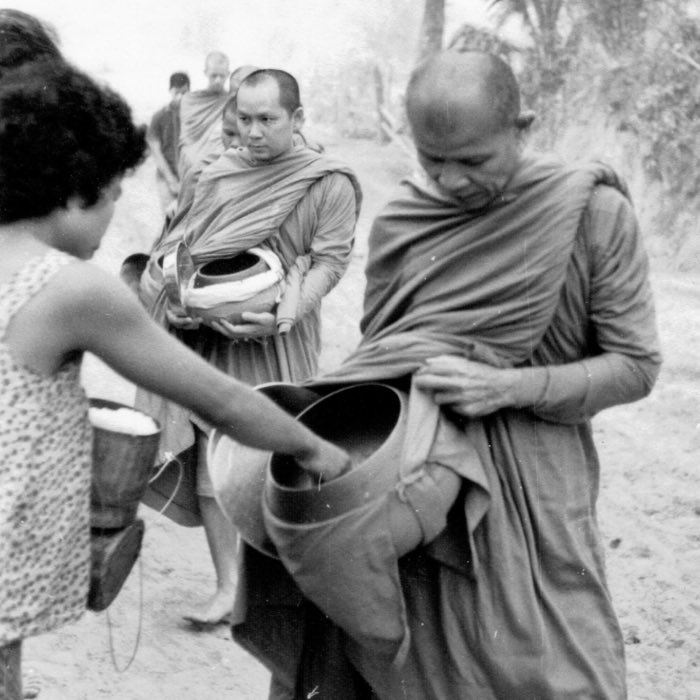

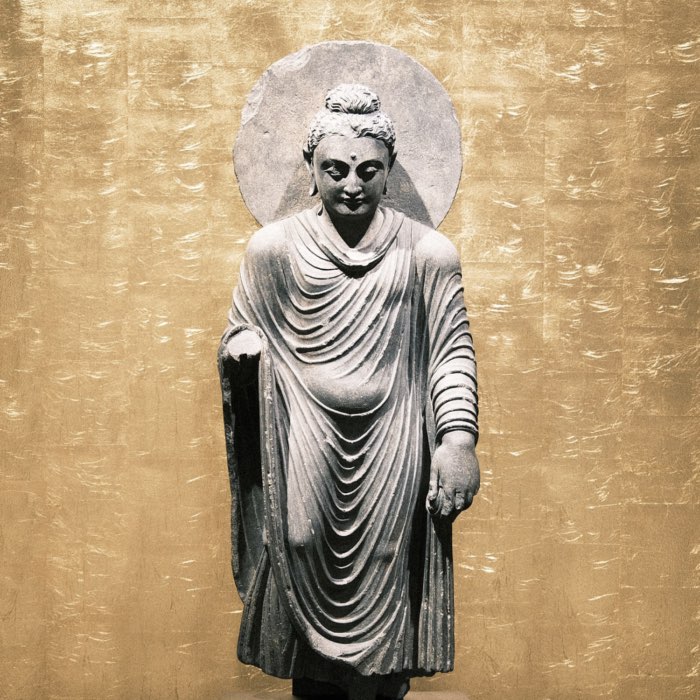

During the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, the Indian subcontinent saw the rise of powerful kingdoms and religious reform movements. The birth of Jainism and Buddhism, led by Mahavira and Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) respectively, offered alternative spiritual paths to Vedic orthodoxy. The Magadha kingdom emerged as a dominant power, culminating in the establishment of the Mauryan Empire (321–185 BCE).

The Mauryan Empire represents a watershed moment in Indian history, marking the first large-scale political unification of the subcontinent. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya, the empire reached its zenith under Ashoka the Great, who embraced Buddhism and spread its teachings across Asia.

Traditional depiction of the Maurya Empire under Ashoka as a solid mass of Maurya-controlled territory, c. 250 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ashoka’s edicts, inscribed on pillars and rock surfaces, highlight the ethical and administrative ideals of the Mauryan state. These inscriptions, written in multiple languages and scripts, reflect a sophisticated bureaucratic system and a commitment to governance based on dharma (moral law). The Mauryan Empire also facilitated economic prosperity through extensive trade networks and agricultural productivity.

Ashoka pillar at Vaishali. Ashoka’s edicts, inscribed on pillars and rock surfaces, highlight the ethical and administrative ideals of the Mauryan state, rooted in the dharma, the Buddhist concept of moral law. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

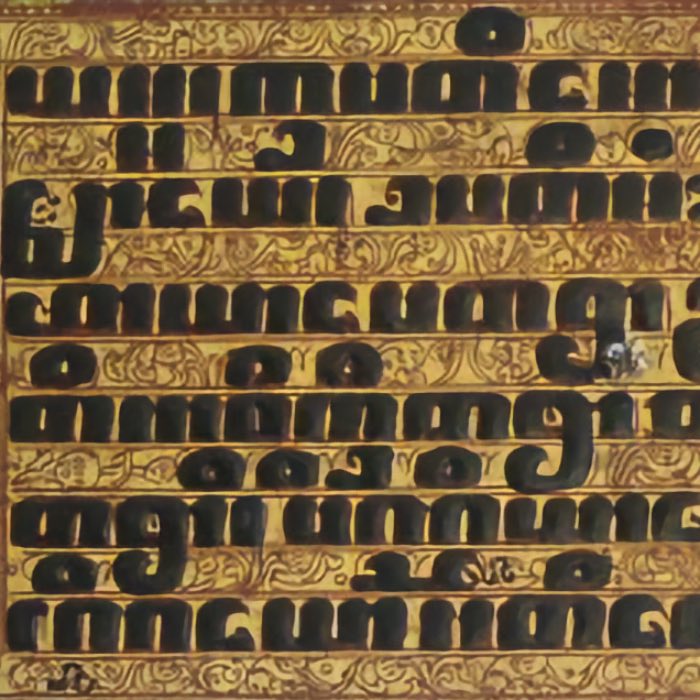

Left: Example inscription on the Minor Pillar Edict on the Sarnath pillar of Ashoka, 3rd century BCE. The edict is written in Prakrit, using the Brahmi script, and is one of the earliest known inscriptions of Ashoka. The edicts usually proclaim Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism and his commitment to the welfare of his subjects, before common themes of dharma and moral conduct. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Maurya statuette, 2nd century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire (ca. 320–550 CE) is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of India due to its unparalleled achievements in art, science, and literature. This period saw the flourishing of Sanskrit literature, including works like Kalidasa’s plays, and significant advancements in mathematics, such as the concept of zero and the decimal system.

Map of the Gupta Empire c. 420 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Guptas also fostered religious and cultural pluralism, with Hinduism reaching new heights of expression through temple architecture and sculpture. Simultaneously, Buddhism and Jainism thrived, contributing to the cultural diversity of the era. The Gupta period left an enduring legacy that shaped the cultural identity of India.

Left: Standing Buddha in red sandstone, Art of Mathura, Gupta period c. 5th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Sculpture of Vishnu (red sandstone), 5th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: Jain tirthankara relief Parshvanatha on Kahaum pillar erected by person named Madra during the reign of Skandagupta. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: A tetrastyle prostyle Gupta period temple at Sanchi besides the Apsidal hall with Maurya foundation, an example of Buddhist architecture and Hindu architecture side by side, 5th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Medieval period

Following the decline of the Gupta Empire, India witnessed the rise of regional powers such as the Chalukyas, Pallavas, Rashtrakutas, and Pala dynasties. The south saw the flourishing of the Tamil kingdoms — the Cholas, Cheras, and Pandyas — which established maritime trade networks with Southeast Asia and contributed to the spread of Indian culture abroad.

Chola Empire under Rajendra Chola, c. 1030. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

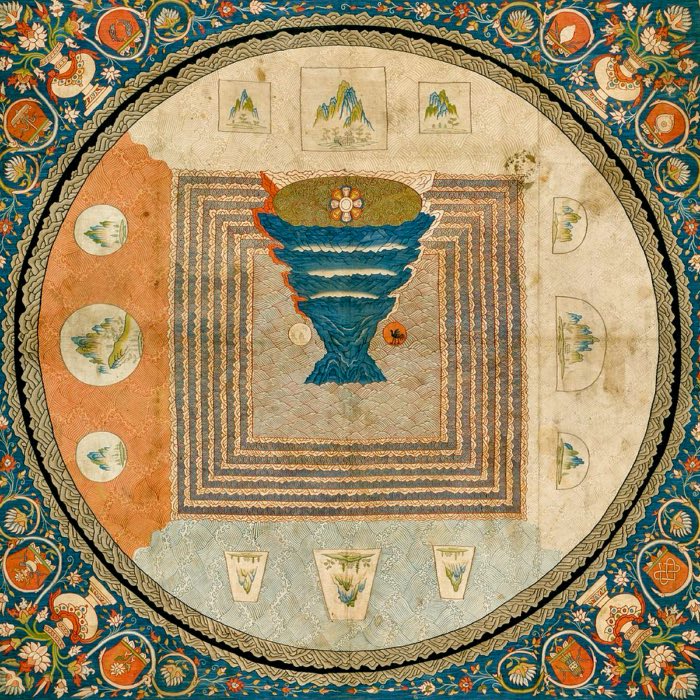

Between the 8th and 12th centuries CE, significant cultural and religious developments took place, including the Bhakti and Tantric movements. These movements emphasized personal devotion and esoteric practices, leading to a diversification of religious expressions.

The Islamic era

The Islamic era began with the invasions of Mahmud of Ghazni (11th century) and later Muhammad Ghori (12th century), leading to the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206. This period saw the synthesis of Indian and Persian cultures, giving rise to Indo-Islamic art, architecture, and literature. The Sufi and Bhakti movements flourished, promoting syncretic traditions and fostering communal harmony.

Mughal Empire

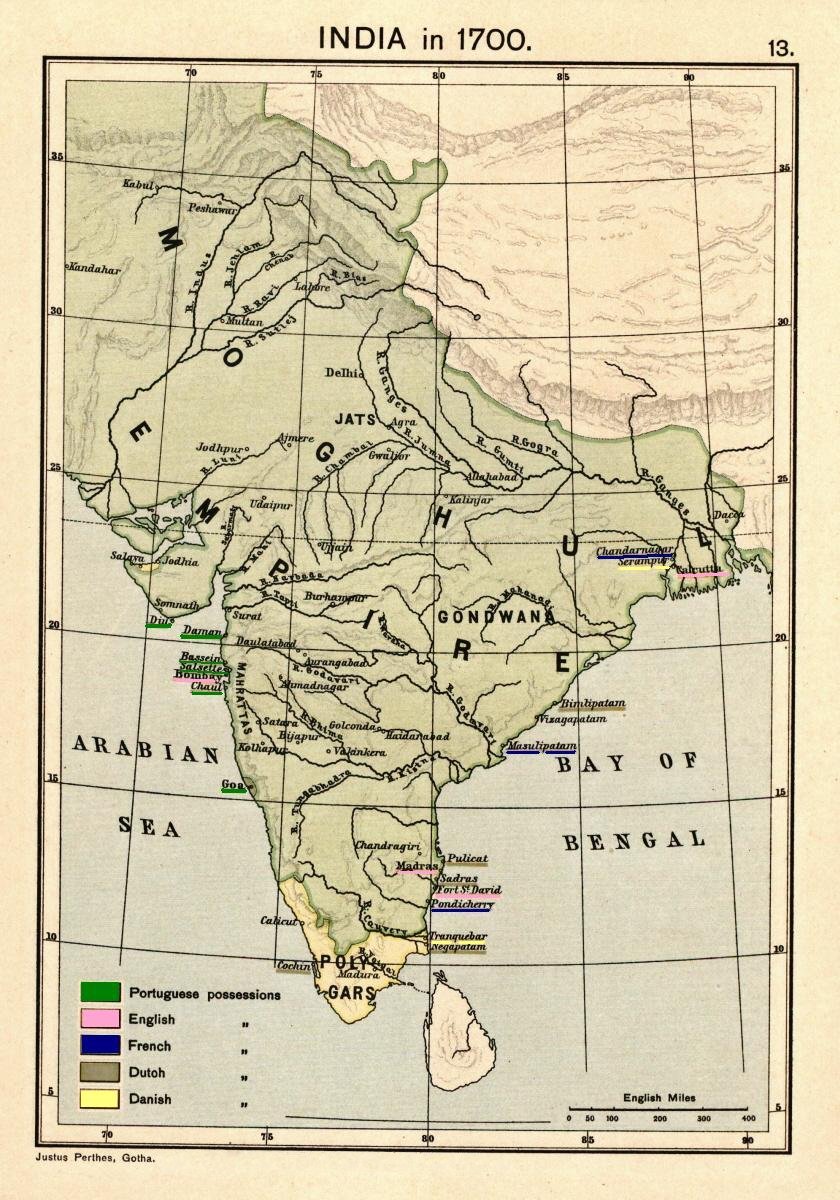

The Mughal Empire (1526–1857) marked a new era of political stability and cultural brilliance. Under rulers like Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb, the empire expanded across much of the subcontinent. The Mughals patronized art, literature, and architecture, resulting in iconic monuments such as the Taj Mahal and the Red Fort.

Left: Map of the Mughal Empire at its peak in year 1700. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: 18th-century political formation in India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Akbar’s policy of religious tolerance and his efforts to foster dialogue between different faiths had a lasting impact on India’s social fabric. The Mughal period also saw economic prosperity, with India becoming a major center of global trade.

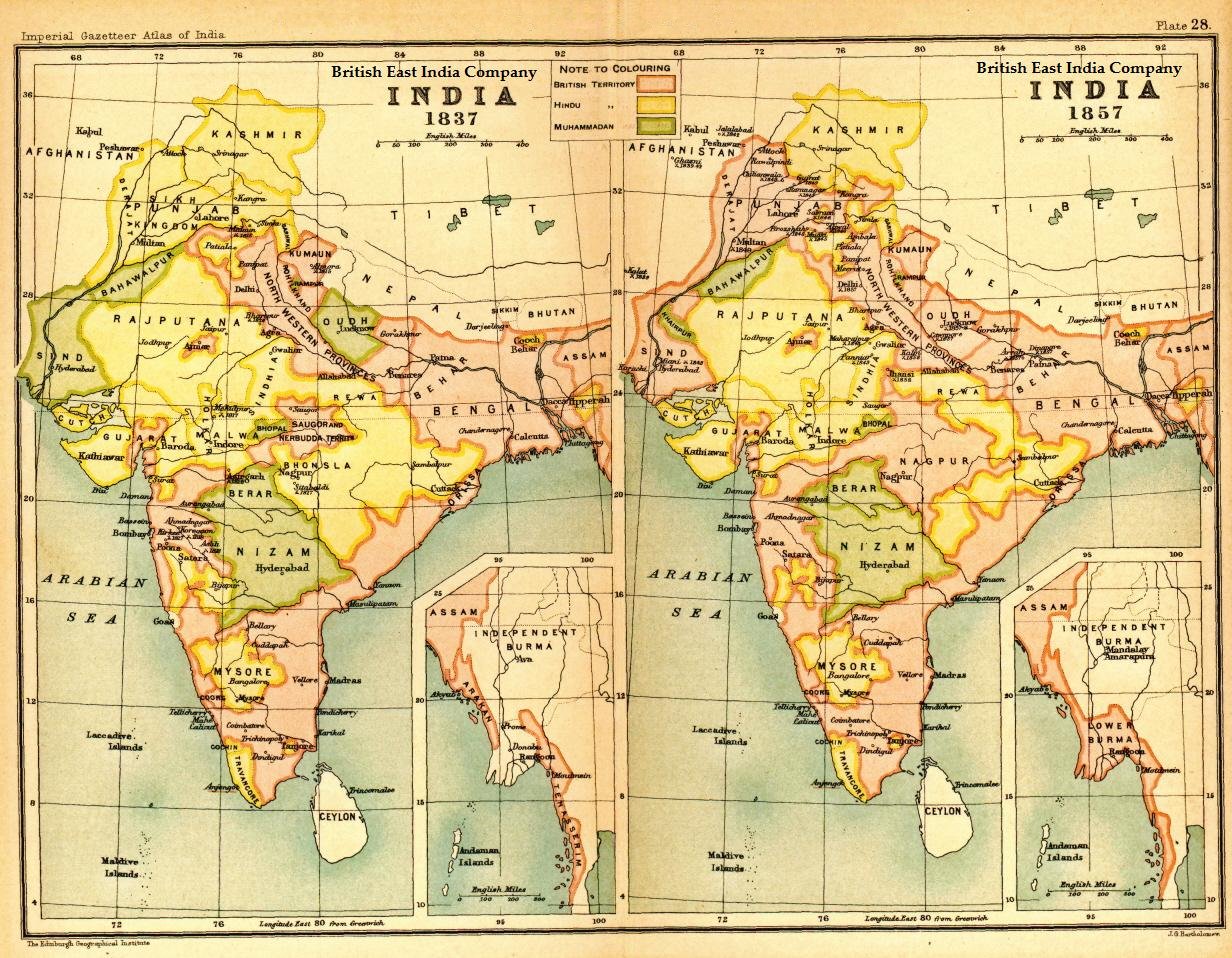

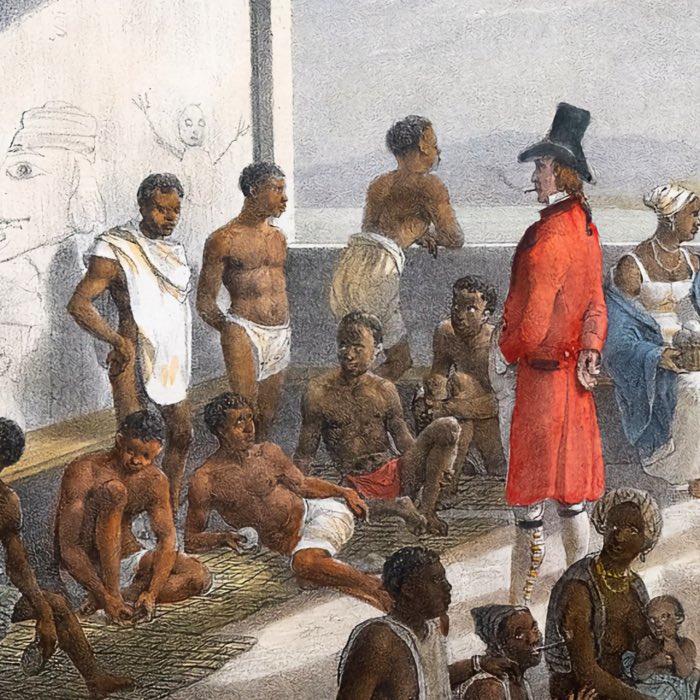

Colonial period and the struggle for independence

The decline of the Mughal Empire in the 18th century created a power vacuum that was gradually filled by European colonial powers, particularly the British East India Company. Following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the company established its dominance over Bengal and expanded its control across India.

India in 1837 and 1857 showing East India Company (pink) and other territories. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

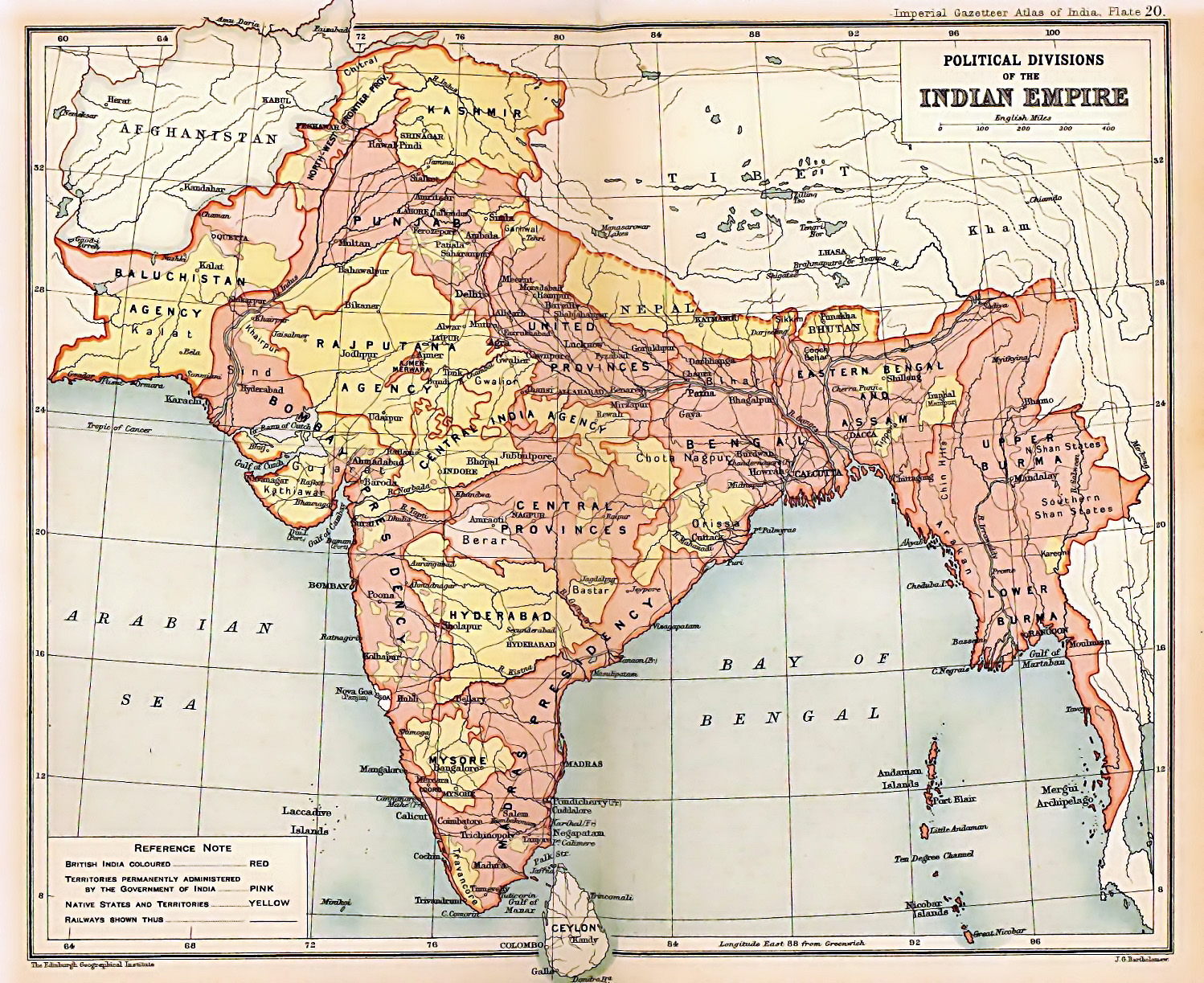

The 19th century witnessed significant socio-economic changes under British rule, including the introduction of Western education, railways, and legal systems. However, British policies also led to economic exploitation and social unrest.

The British Indian Empire in 1909. British India is shown in pink; the princely states in yellow. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Map of the prevailing religions of the British Indian empire based on district-wise majorities based on the Indian census of 1909. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Indian independence movement gained momentum in the early 20th century, with leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Subhas Chandra Bose spearheading the struggle against colonial rule. Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent resistance (Satyagraha) inspired millions and played a crucial role in India’s path to independence.

Post-independence India

India achieved independence on August 15, 1947, but the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan led to significant communal violence and mass migrations. Under Nehru’s leadership, India adopted a socialist-inspired economic model and pursued a policy of non-alignment during the Cold War.

The partition of India: green regions were all part of Pakistan by 1948, and orange ones part of India. The darker-shaded regions represent the Punjab and Bengal provinces partitioned by the Radcliffe Line. The grey areas represent some of the key princely states that were eventually integrated into India or Pakistan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Subsequent decades saw significant developments in agriculture (Green Revolution), industry, and science. India emerged as a major player in global politics, championing decolonization and South-South cooperation.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, economic liberalization transformed India into one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Advances in technology, space exploration, and education positioned India as a global leader in various fields.

Modern India: Challenges and achievements

Today, India is a vibrant democracy with a rich cultural heritage and a diverse population. It faces significant challenges, including poverty, environmental degradation, and social inequality. However, it also boasts remarkable achievements in technology, medicine, and space exploration. India’s cultural influence continues to grow, with its diaspora contributing to global innovation and cultural exchange.

Timeline summary

- ca. 3300 BCE – Rise of the Indus Valley Civilization

- ca. 1700 BCE – Decline of the Indus Valley Civilization

- ca. 1500–600 BCE – Vedic Age and composition of the Vedas

- 6th–4th centuries BCE – Rise of Jainism and Buddhism; establishment of the Magadha kingdom

- 321–185 BCE – Mauryan Empire, peak under Ashoka the Great

- ca. 320–550 CE – Gupta Empire, golden age of Indian culture

- 8th–12th centuries CE – Rise of regional powers; Bhakti and Tantric movements

- 1206 – Establishment of the Delhi Sultanate

- 1526–1857 – Mughal Empire, cultural and economic prosperity

- 1757 – British East India Company gains control after the Battle of Plassey

- 1857–1858 – Indian Rebellion, end of Mughal rule, beginning of British Raj

- 1947 – India gains independence and partition into India and Pakistan

- 1960s–1970s – Green Revolution; industrial and scientific progress

- 1991 – Economic liberalization and rapid growth

- 21st century – India emerges as a global leader in technology and space exploration

Cultural parallels with other civilizations

Indian civilization shares several thematic parallels with other early civilizations, such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China. Like these cultures, India’s development was deeply tied to its river systems, which supported agriculture and trade. However, the spiritual and philosophical focus of Indian culture — evident in the Vedic traditions and later religious movements — sets it apart.

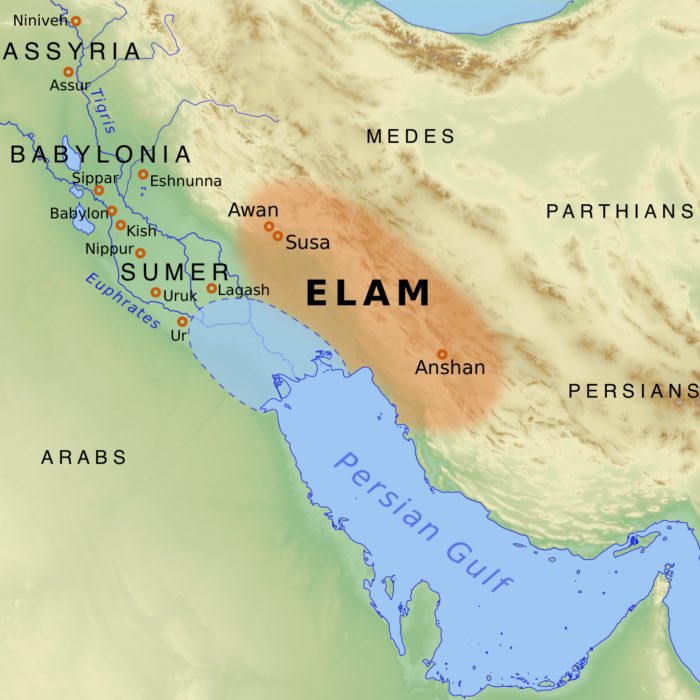

Left: Archaeological discoveries suggest that trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus were active during the 3rd millennium BCE, leading to the development of Indus–Mesopotamia relations. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus would have been significantly shorter due to lower sea levels in the 3rd millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

While Mesopotamia and Egypt emphasized monumental architecture and centralized governance, Indian civilization demonstrated a unique balance between urbanization, spirituality, and intellectual pursuits. Its legacy, shaped by both continuity and adaptation, remains one of the most enduring in human history.

Left: Fertility figurine of the Halaf culture, Mesopotamia, 6000–5100 BCE, Louvre. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0) – Right: Fertility figurine from Mehrgarh, Indus Valley, 7000–3100 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Philosophical and theological divergences with Zoroastrianism

While Zoroastrianism and Indian religions share common Indo-Iranian roots, their theological and philosophical trajectories diverged significantly. Zoroastrianism emphasized dualism, moral accountability, and the linear progression of cosmic time, culminating in the ultimate triumph of good. Indian thought, by contrast, embraced cyclical cosmologies and pluralistic paths to liberation.

However, both traditions emphasized the moral responsibility of individuals in maintaining cosmic order, whether through adherence to asha (truth) in Zoroastrianism or dharma (duty) in Indian traditions. The emphasis on fire as a sacred element also reflects their shared heritage, with Zoroastrian fire temples paralleling Vedic fire rituals.

Potential external influences: Indo-Iranian connections

The Vedic religion shared many features with the contemporaneous Indo-Iranian traditions, including those represented in Zoroastrianism. Both traditions emerged from a common Proto-Indo-Iranian heritage, reflected in shared linguistic roots and cosmological concepts. For instance:

- The dualistic struggle between Ahura Mazda (order) and Angra Mainyu (chaos) in Zoroastrianism parallels the Vedic opposition between rita (cosmic order) and anrita (disorder).

- Deities such as Mitra and Varuna appear in both Vedic and Indo-Iranian traditions, though their roles evolved differently in each context. In the Rigveda, Mitra and Varuna uphold societal order and truth, while in Zoroastrianism, Mithra becomes a protector of covenants and truth.

Despite these shared elements, Vedic religion diverged significantly, retaining its polytheistic structure while Zoroastrianism developed a monotheistic and dualistic framework. This divergence illustrates how shared cultural roots can yield distinct theological systems based on historical and social contexts.

Independent creations: Indigenous contributions to Indian thought

While Indo-Iranian connections influenced Vedic religion, many aspects of Indian spirituality arose independently or through interactions with pre-Vedic traditions. The emphasis on meditation, self-realization, and the renunciation of worldly attachments, which became central to Indian philosophy, likely evolved from indigenous practices.

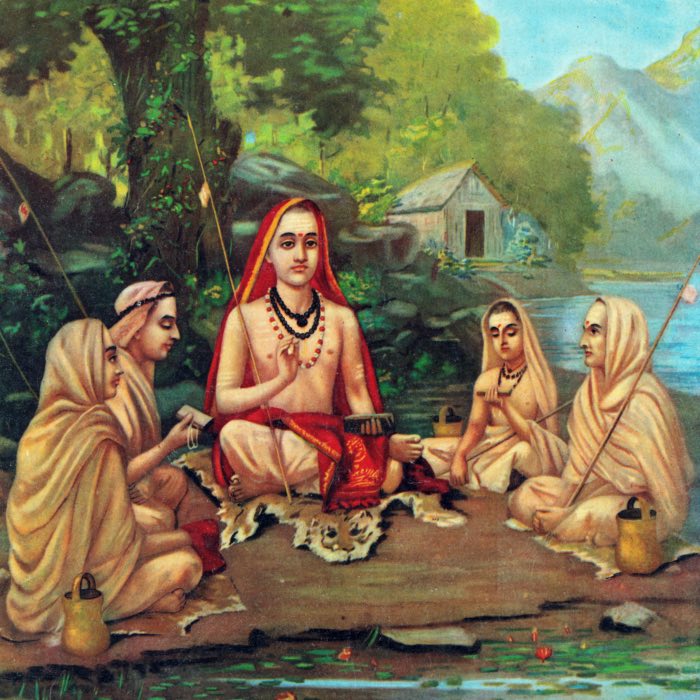

The Upanishads (ca. 800–500 BCE), philosophical texts appended to the Vedas, represent a uniquely Indian contribution to global religious thought. They explore metaphysical questions about the nature of existence, the self, and ultimate reality. The idea of moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth) and the identification of Atman with Brahman laid the groundwork for later developments in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Similarly, the ascetic traditions that gave rise to Jainism and Buddhism likely drew on indigenous practices of renunciation and meditation. Figures such as Mahavira and the Buddha synthesized these practices into comprehensive ethical and philosophical systems, offering alternatives to Vedic orthodoxy.

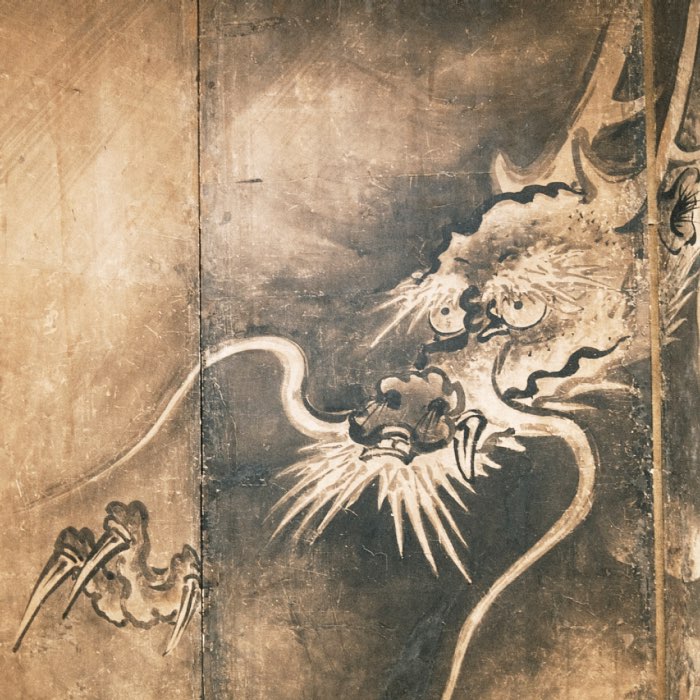

Cultural and religious contributions

Indian civilization has made profound contributions to global culture, particularly in religion and philosophy. Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, all originating in India, have influenced spiritual practices worldwide. The Upanishads and other philosophical texts explored themes of self-realization, the nature of the universe, and ethical living, laying the foundation for Indian metaphysics.

India’s cultural heritage also extends to art, music, and dance, with classical traditions such as Bharatanatyam and Carnatic music reflecting the depth and richness of Indian creativity. The subcontinent’s ancient traditions continue to inspire modern thought and practice.

Broader significance

The development of Indian civilization illustrates the interplay between geography, innovation, and cultural evolution. From the urban sophistication of the Indus Valley to the intellectual flowering of the Gupta Empire, India’s history reflects human creativity and resilience. Like Mesopotamia, where the first settlements emerged around 5500 BCE, and Egypt, where centralized civilizations arose by 3100 BCE, Indian civilization began with the Indus Valley’s urban centers around 3300 BCE. Similarly, parallels can be drawn to China, where Neolithic cultures like the Yangshao emerged around 5000 BCE and culminated in early dynasties. While all these civilizations were deeply shaped by river systems, their trajectories diverged, with Indian civilization uniquely balancing urban planning, spiritual exploration, and intellectual achievements. Understanding this trajectory enriches our appreciation of India’s role in the shared heritage of humanity.

References

- Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India, 2009, Pearson Education, ISBN: 978-8131716779

- Romila Thapar, Early India: From the Origins to CE 1300, 2003, Penguin, ISBN: 978-0143029892

- A.L. Basham, The Wonder That Was India, 1985, Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN: 978-0283992575

- John Keay, India: A History, 2022, William Collins, ISBN: 978-0007307753

- Gregory Possehl, The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, 2010, Altamira, ISBN: 978-8178292915

- R.S. Sharma, India’s Ancient Past, 2011, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195687859

- D.N. Jha, Ancient India in Historical Outline, 2006, Manohar Publishers, ISBN: 978-8173042164

- Burton Stein, A History of India, 2010, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405195096

- S.R. Rao, Lothal and the Indus Civilization, 1974, Asia Publishing House, ISBN: 978-0210222782

- Michel Danino, The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvati, 2010, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0143068648

- McIntosh, Jane, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives, 2008, ISBN: 978-1-57607-907

- Bryant, E. F.,The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate, 2004, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195169478

- Flood, G., An Introduction to Hinduism, 1996, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521438780

- Boyce, M., Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, 1979, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415239035

- Parpola, A., The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, 2015, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0190226923

- Wikipedia article on the History of Indiaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Indus Valley Civilizationꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Indo-Mesopotamia relationsꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Religion of the Indus Valley Civilisationꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Vedic periodꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Maurya Empireꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Gupta Empireꜛ

comments