Origin of the Chinese civilization

In the previous posts, we explored the emergence of civilization in Mesopotamia and Egypt, where the Tigris, Euphrates, and Nile rivers nurtured early agricultural societies and centralized political systems. The earliest settlements in Mesopotamia date back to the Ubaid period (ca. 5500–3700 BCE), while the rise of urban centers like Uruk marked the beginning of structured civilizations around 3100 BCE. In Egypt, the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3100 BCE established one of history’s first centralized states, leveraging the predictable floods of the Nile to support their society. These civilizations laid the groundwork for governance, technological innovation, and cultural identity.

A late Shang-era (13th–11th century BCE) ding (bronze vessel) with taotie (monster mask) motif. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Turning our focus eastward, the origin of Chinese civilization presents a similarly remarkable story of human development. Rooted in the fertile lands along the Yellow River (Huang He) and the Yangtze River, Chinese civilization evolved independently, forming a unique cultural and historical trajectory. This civilization, which dates back to approximately 5000 BCE, also laid the foundations for governance, agriculture, and technological advancements that have influenced human history for millennia.

While Chinese civilization developed independently, it shares thematic parallels with Mesopotamia and Egypt, including the rise of riverine agricultural societies, centralized governance, and innovations in writing and technology. At the same time, its development diverged in notable ways, influenced by distinct geographical and cultural factors that make its trajectory uniquely fascinating.

Geographical foundations of Chinese civilization

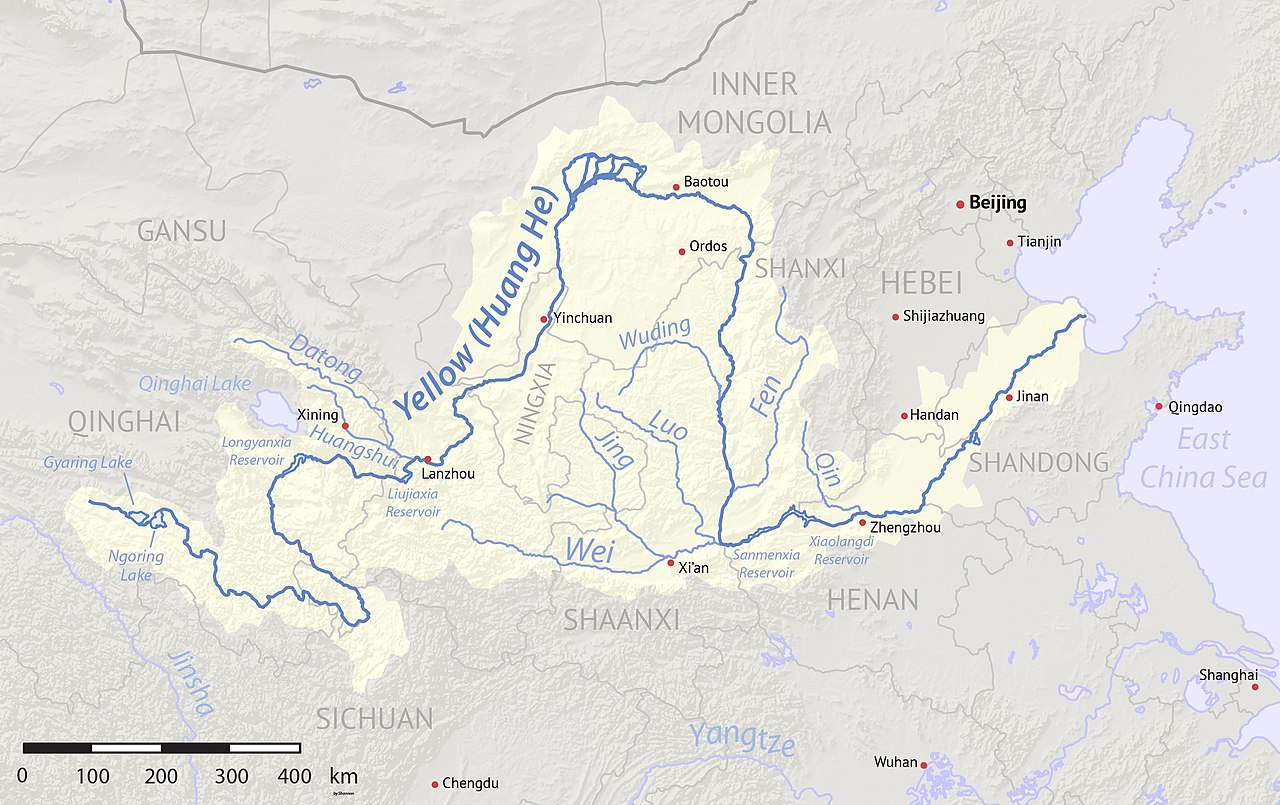

China’s geography significantly influenced the development of its civilization. The Yellow River basin, often called “the cradle of Chinese civilization”, provided the fertile loess soil needed for agriculture. The predictable flooding of the Yellow River, although sometimes destructive, allowed early farmers to cultivate millet, a staple crop, which supported the growth of sedentary communities. Similarly, the Yangtze River in the south enabled the cultivation of rice, giving rise to diversified agricultural practices.

Map of the Yellow River, whose watershed covers most of northern China and drains to the Yellow Sea. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Map of the Yellow River, whose watershed covers most of northern China and drains to the Yellow Sea. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Asian rice, grown since the 9th millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Asian rice, grown since the 9th millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Natural barriers such as the Himalayas, the Gobi Desert, and vast seas provided protection from invasions, fostering the development of a distinct and continuous culture. At the same time, these features created challenges in uniting the vast and varied landscape, shaping the early political structures of China.

Human settlement and early cultures

Archaeological evidence suggests that human settlements in China date back to the Neolithic period. The Yangshao culture (ca. 5000–3000 BCE), centered along the Yellow River, is one of the earliest known Chinese cultures. It is characterized by painted pottery, rudimentary farming techniques, and the domestication of animals. Villages such as Banpo near present-day Xi’an reveal the social and economic organization of these early societies.

Left: Area of the Yangshao culture (5000–3000 BC) in northern China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Red oval is the late Cishan (another early Neolithic culture, 6500–5000 BCE) and the early Yangshao cultures. After applying the linguistic comparative method to the database of comparative linguistic data developed by Laurent Sagart in 2019 to identify sound correspondences and establish cognates, phylogenetic methods are used to infer relationships among these languages and estimate the age of their origin and homeland. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

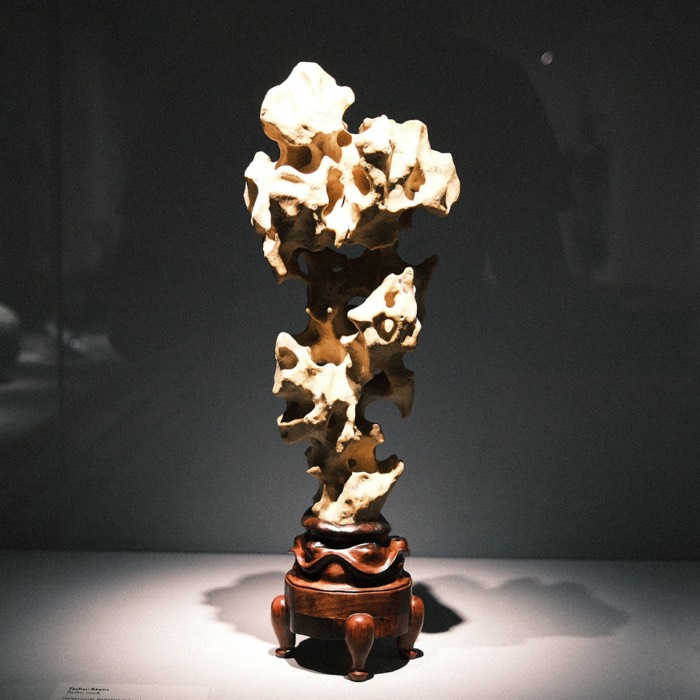

The subsequent Longshan culture (ca. 3000–1900 BCE) marked a significant transition toward more complex societies. This period saw advancements in pottery, the use of jade in ceremonial contexts, and evidence of early forms of urbanization. Fortified settlements and the appearance of oracle bones hint at the beginnings of organized governance and religious practices.

Top: Area of the Longshan culture (3000–2000 BC) in northern China (within the red dashed lines). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Bottom: Regional cultures and local centers of the middle and lower Yellow River valley in the late 3rd millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: White pottery gui, Shandong Museum, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Jade cong from the Hougang II site of the Longshan culture, c. 2500–2000 BCE. National Museum of China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Further historical developments of Chinese civilization

Xia Dynasty (2070–1600 BCE)

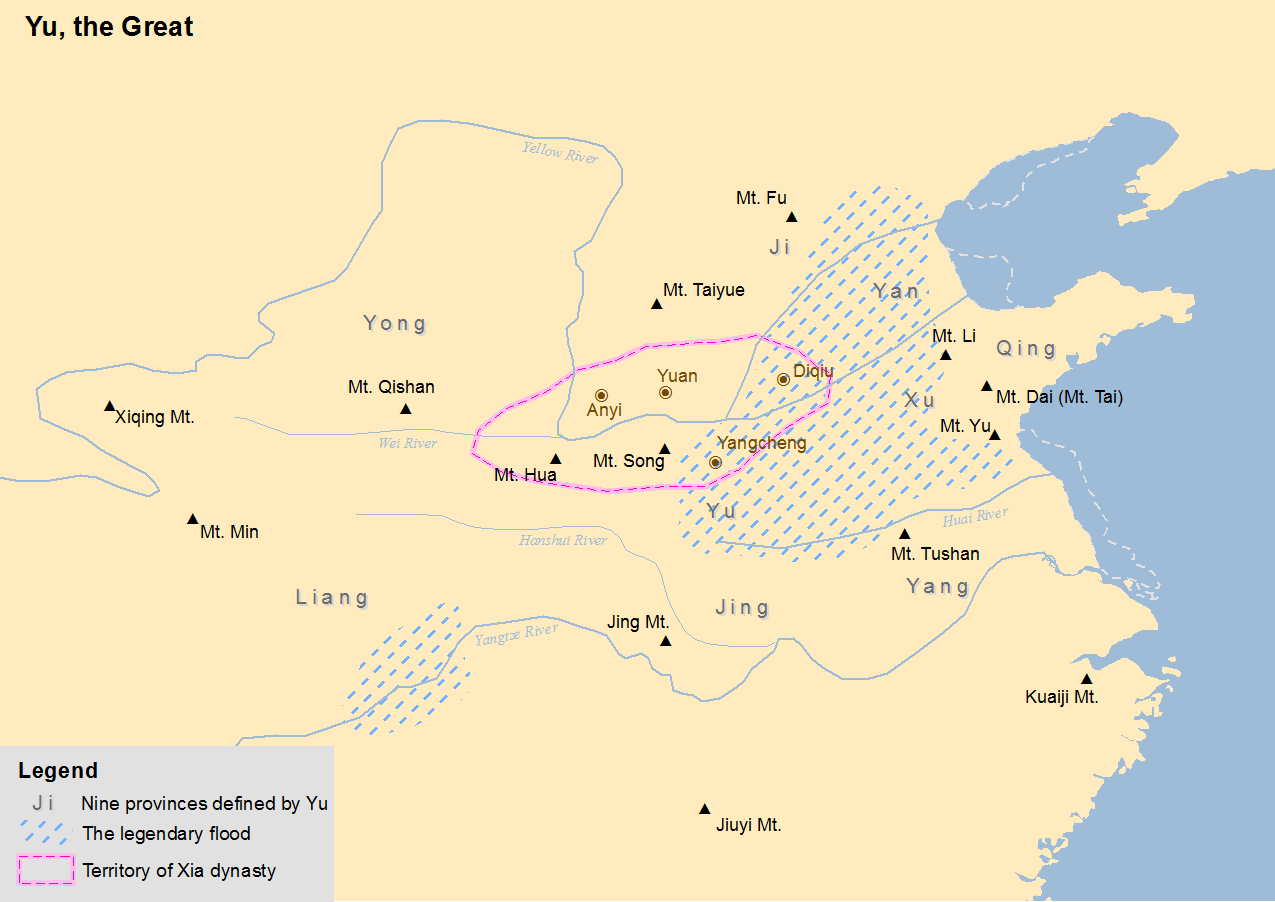

The Xia Dynasty (ca. 2070–1600 BCE) is often considered the first dynasty in Chinese history, though its existence is shrouded in legend. Early Chinese texts, such as the “Records of the Grand Historian” by Sima Qian, describe the Xia as a lineage of rulers who established a hereditary monarchy. Archaeological sites, such as Erlitou in Henan Province, provide evidence of a complex society with palatial buildings, bronze tools, and early forms of writing that might be linked to the Xia.

Approximate location of Xia dynasty (in pink) in traditional Chinese historiography. Because of the lack of written records, the existence of Xia cannot be proven. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Approximate location of Xia dynasty (in pink) in traditional Chinese historiography. Because of the lack of written records, the existence of Xia cannot be proven. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Whether mythical or historical, the Xia Dynasty represents a crucial stage in the consolidation of political authority and the development of centralized governance in ancient China.

Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE)

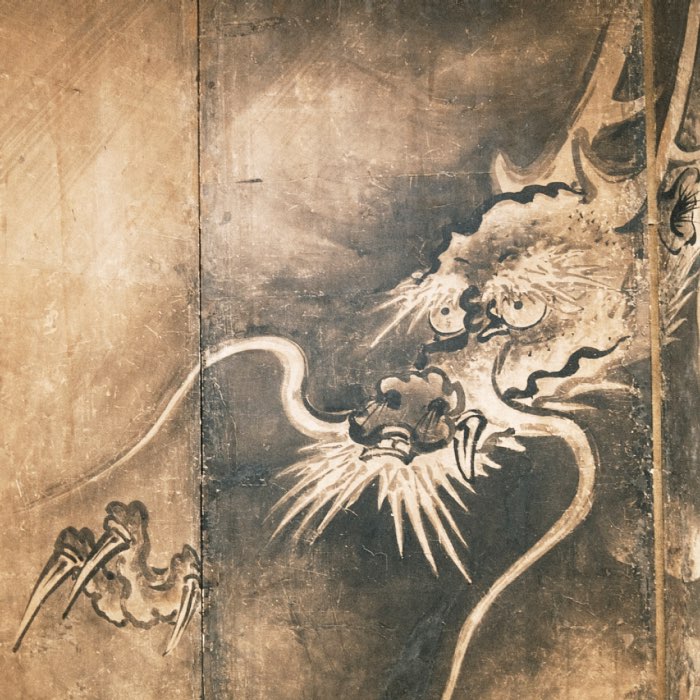

The Shang Dynasty (ca. 1600–1046 BCE) is the first Chinese dynasty for which there is clear archaeological and written evidence. Centered in the Yellow River valley, the Shang established a highly stratified society with a powerful king at its apex. The use of bronze technology flourished during this period, enabling the creation of intricate ceremonial vessels and weapons.

Left: Locations of the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) marked in violet, with Shang capitals in marked by red dots. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: The Shang-era Houmuwu ding, the heaviest piece of bronze work found in China so far. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: A yue bronze axe (battle axe) with head motif, dated to the Shang (1600–1046 BCE). This axe was used in hand-to-hand combat, and was also a ritual object symbolizing power and military authority. The tomb it came from likely belonged to a man of wealth and influence. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5) – Right: Shang jade human figure, tomb of Fu Hao (died c. 1200 BC). Probably derived from a design of the Seima-Turbino culture. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

The Shang are also renowned for their advances in writing. The discovery of oracle bones — used for divination — provides some of the earliest examples of Chinese script, a precursor to modern Chinese characters. These records give insight into the political, religious, and social organization of Shang society, including their reverence for ancestors and their belief in the divine authority of kings.

Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE)

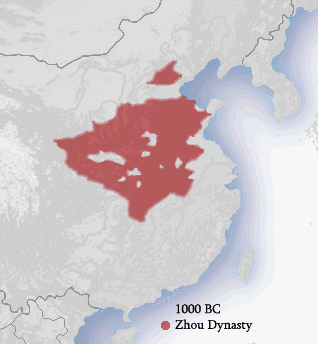

The Zhou Dynasty (ca. 1046–256 BCE) succeeded the Shang and introduced significant political and philosophical changes. The Zhou justified their rule through the concept of the “Mandate of Heaven”, a belief that the right to rule was granted by a divine force and could be revoked if a ruler failed to govern justly.

Left: Territory of the Western Zhou c. 1000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Western Zhou bronze pot (896 BC), Fufeng County, Shaanxi, Baoji Zhouyuan Museum, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

During the Western Zhou period (ca. 1046–771 BCE), feudalism emerged as a dominant political system, with the king delegating authority to regional lords. This period also saw advancements in agriculture, metallurgy, and urban planning.

The Eastern Zhou period (ca. 770–256 BCE) was marked by the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, times of significant political fragmentation and intellectual flourishing. Thinkers like Confucius, Laozi, and Mozi laid the philosophical foundations that would shape Chinese culture for centuries.

The Warring States, c. 260 BCE. During this period, the states of China were engaged in a series of military conflicts that eventually led to the unification of China under the Qin Dynasty. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Warring States, c. 260 BCE. During this period, the states of China were engaged in a series of military conflicts that eventually led to the unification of China under the Qin Dynasty. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

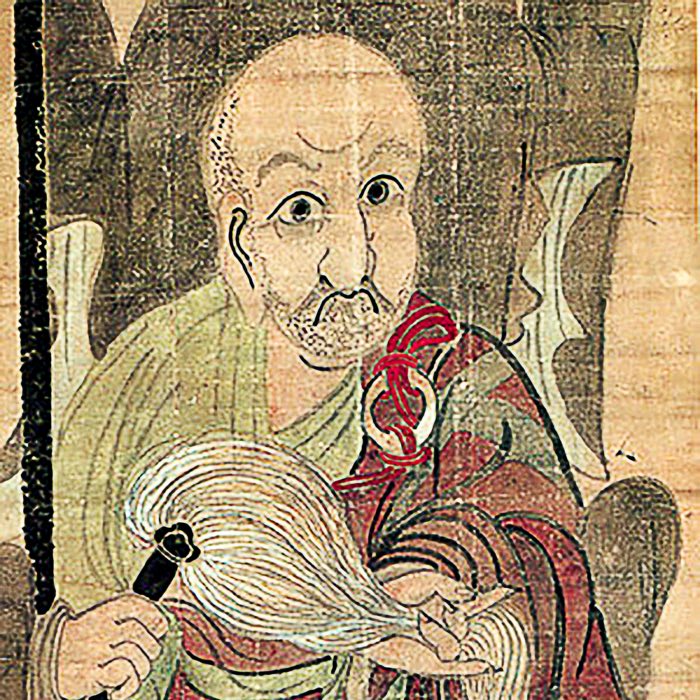

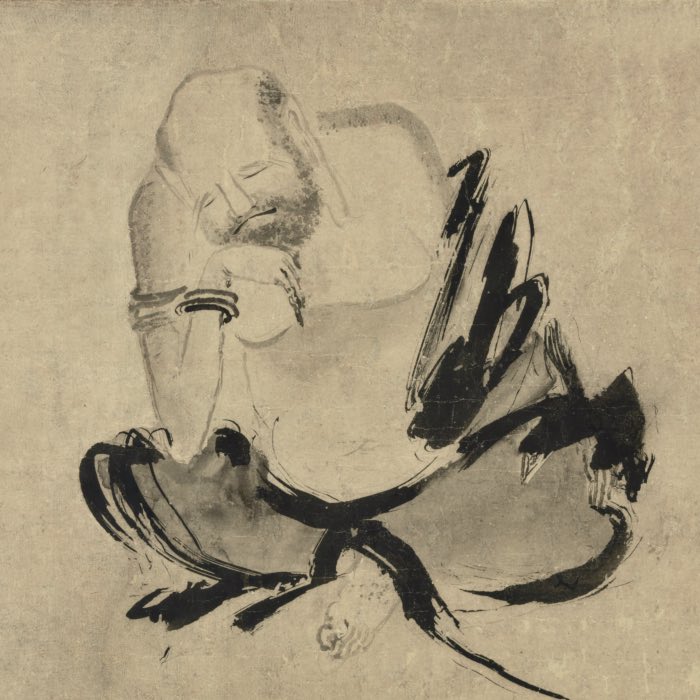

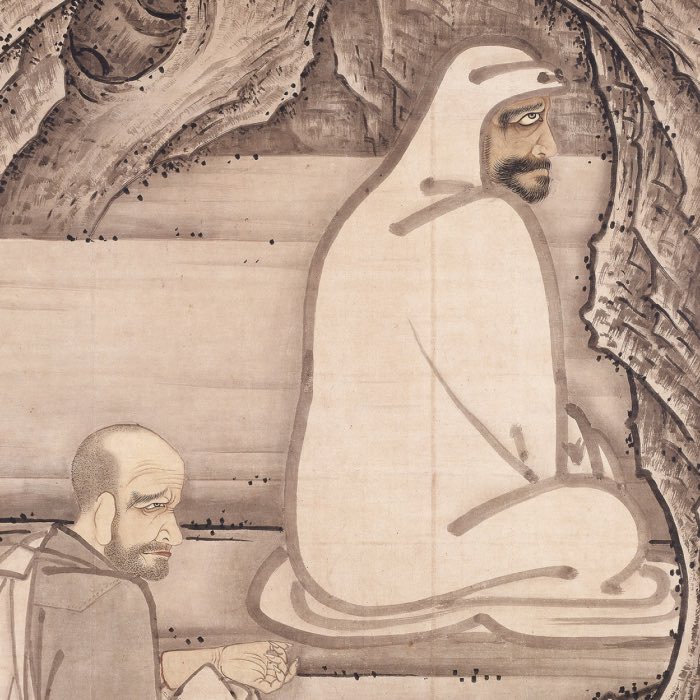

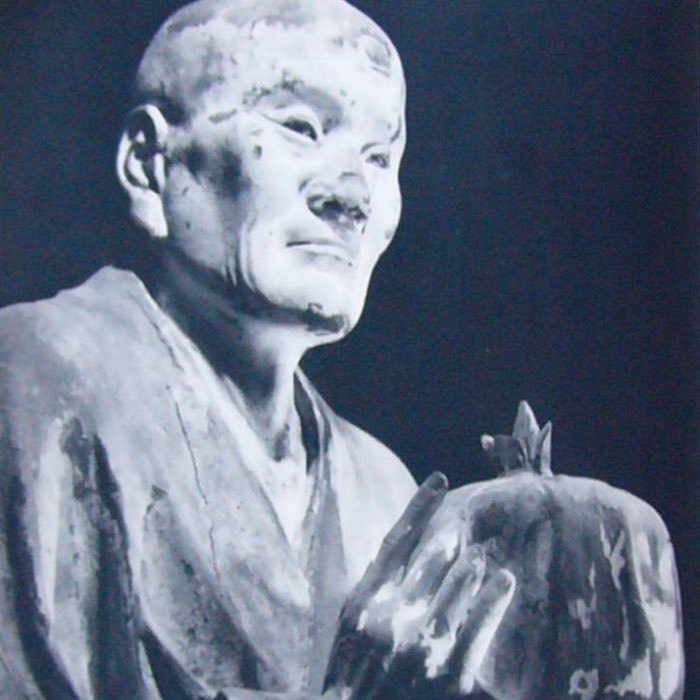

Left: Portrait of Laozi riding an ox by Zhang Lu, 15th- or 16th-century painting, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), China. Laozi (born in the 6th century BCE) is the legendary founder of Daoism, a philosophical and religious tradition in China that emphasizes harmony with nature and the pursuit of inner peace. The subject deals with the story of Laozi riding an ox through a pass. It is said that with the fall of the Chou dynasty, Laozi decided to travel west through the Han Valley Pass. The Pass Commissioner, Yin-hsi, noticed a trail of vapor emanating from the east, deducing that a sage must be approaching. Not long after, Laozi riding his ox indeed appeared and, at the request of Yin-hsi, wrote down his famous Dao-te ching, leaving afterwards. This story thus became associated with auspiciousness. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Middle: Portrait of Confucius by Wu Daozi, 685-758, Tang Dynasty (618–907), China. Confucius (551-479 BCE) was a Chinese philosopher and teacher whose ideas have profoundly influenced Chinese culture and governance. His teachings emphasized moral values, social harmony, and the importance of education. Confucianism became a dominant philosophical and ethical system in China, shaping the behavior of individuals and the structure of society. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Portrait of Mencius, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), China. The Confucian philosopher Mencius was one of several critics of Mozi, in part because Mozi’s philosophy was believed to lack filial piety. Mencius is known for his belief that human nature is inherently good and that people are capable of moral self-cultivation. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

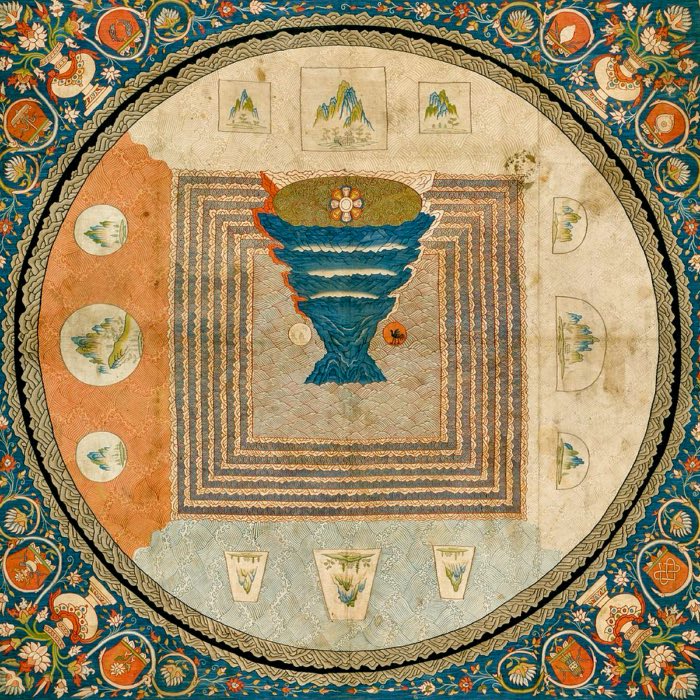

Emergence of key philosophical and religious traditions

During the Zhou Dynasty, several key philosophical and religious traditions emerged, shaping Chinese thought and culture:

- Confucianism: Founded by Confucius (551–479 BCE) during the late Zhou Dynasty, Confucianism emphasized morality, social harmony, and proper governance. It became the cornerstone of Chinese society and political philosophy.

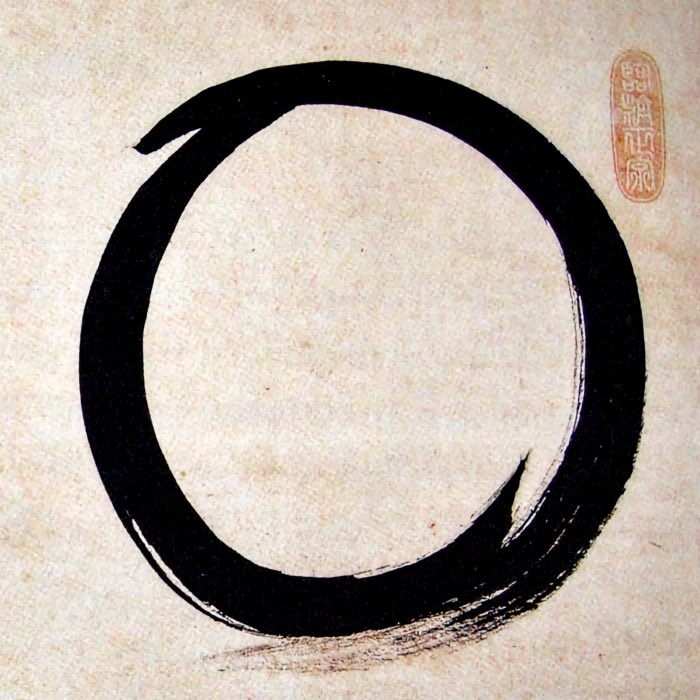

- Daoism: Attributed to Laozi, Daoism emerged around the same period as Confucianism. It advocates living in harmony with the Dao (the Way) and emphasizes simplicity and naturalness.

- Legalism: During the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), Legalism emerged as a school of thought advocating strict laws and centralized control. It greatly influenced the governance of the Qin Dynasty.

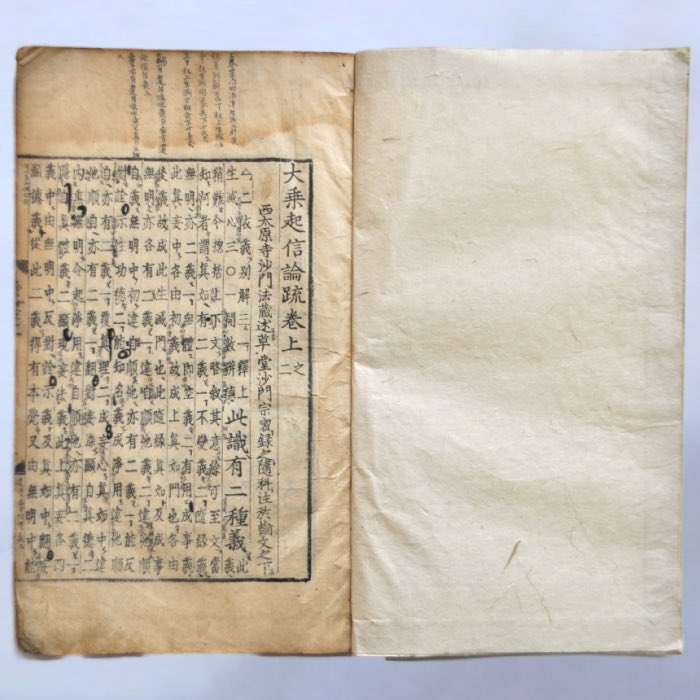

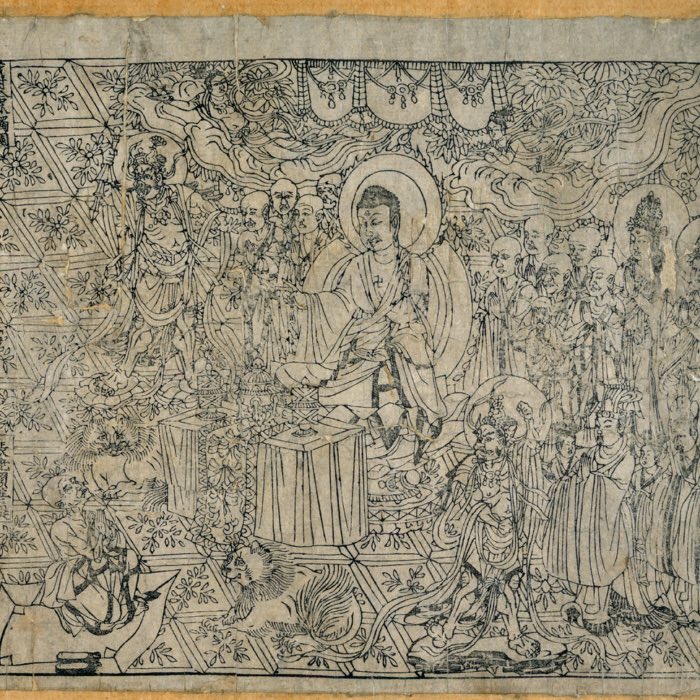

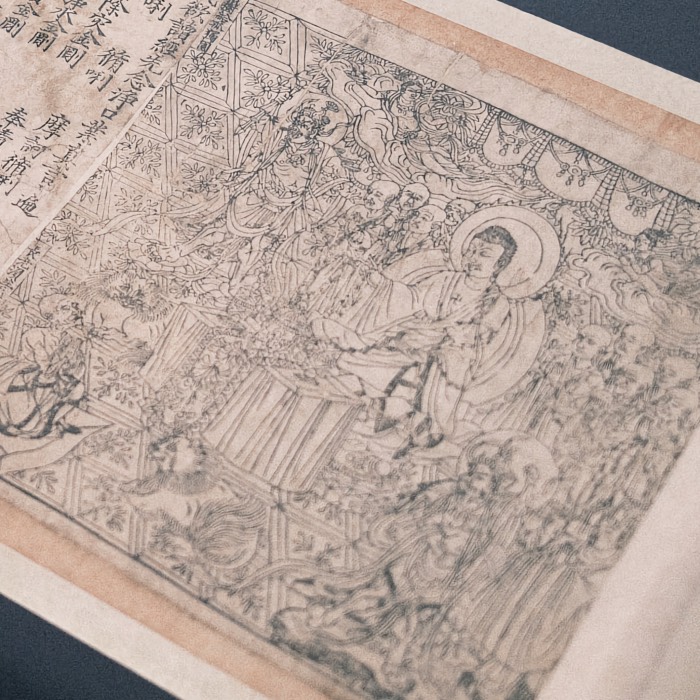

- Buddhism: Introduced to China during the Han Dynasty (ca. 1st century CE), Buddhism became a major spiritual and cultural force, influencing art, literature, and philosophy.

- Neo-Confucianism: In response to the spread of Buddhism and Daoism, Neo-Confucianism arose during the Song Dynasty, synthesizing elements of all three traditions. Thinkers like Zhu Xi played a crucial role in its development.

Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE)

The Qin Dynasty marked the first unification of China under a centralized imperial government. Founded by Qin Shi Huang, the dynasty implemented significant administrative, legal, and infrastructural reforms. Standardization of weights, measures, currency, and writing systems facilitated greater cohesion across the empire. Additionally, major projects like the initial construction of the Great Wall and the Terracotta Army showcased the Qin’s focus on consolidating power and defense.

The Qin state and main polities in 221 BC, with the capital Xianyang (red dot). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

However, harsh governance and heavy taxation led to widespread unrest, resulting in the dynasty’s collapse shortly after Qin Shi Huang’s death.

Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE)

The Han Dynasty succeeded the Qin and is often considered a golden age in Chinese history. It was characterized by territorial expansion, economic prosperity, and cultural flourishing. Emperor Wu of Han played a pivotal role in expanding the empire and establishing the Silk Road, which facilitated trade and cultural exchange with Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

Map of the Han Dynasty 195 BCE: Thirteen direct-controlled commanderies including the capital region (yellow) and ten semi-autonomous kingdoms. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Confucianism became the official ideology during the Han period, shaping Chinese education, governance, and social values. Advances in science, technology, and literature, such as the invention of paper and notable works like the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, marked this era.

Provinces and commanderies in 219 CE, the penultimate year of the Han dynasty. Shown are both, the Principalities and centrally-administered commanderies and the protectorate of the western regions (Tarim Basin). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Three Kingdoms and Jin Dynasty (220–420)

Following the fall of the Han Dynasty, China entered a period of fragmentation known as the Three Kingdoms (220–280 CE). The kingdoms of Wei, Shu, and Wu vied for control, leading to significant cultural and military developments. This period, though short-lived, became a rich source of historical and literary inspiration, exemplified by the Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

The Jin Dynasty (265–420 CE) briefly reunified China but faced internal strife and invasions by northern nomadic groups. The eventual collapse of the Jin led to the era of the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Southern and Northern Dynasties.

Sui Dynasty (581–618)

After nearly three centuries of division, the Sui Dynasty reunified China. The Sui emperors initiated large-scale infrastructure projects, including the construction of the Grand Canal, which facilitated trade and communication between northern and southern China. Despite its achievements, heavy taxation and forced labor led to widespread discontent, resulting in the dynasty’s fall.

Sui dynasty c. 609 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Tang Dynasty (618–907)

The Tang Dynasty is renowned for its cultural, political, and economic achievements. Under Tang rule, China became one of the most powerful and cosmopolitan empires of its time. The Silk Road flourished, promoting trade and cultural exchange with India, Persia, and the Byzantine Empire.

Tang circuits in 742. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Tang era saw the rise of great poets like Li Bai and Du Fu, advancements in art and architecture, and the spread of Buddhism, which profoundly influenced Chinese culture. The dynasty’s decline was marked by the An Lushan Rebellion and internal strife, leading to its eventual fall.

Song Dynasty (960–1279)

The Song Dynasty, though politically weaker than its predecessors, experienced an economic and cultural renaissance. Advances in agriculture, technology, and commerce transformed China into a prosperous and urbanized society. The invention of gunpowder, the compass, and movable type printing during this period had a lasting impact on world history.

The Song dynasty at its greatest extent in 1111. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Neo-Confucianism emerged as a dominant intellectual movement, synthesizing Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist thought. Despite its achievements, the Song faced constant threats from northern nomadic groups, culminating in its conquest by the Mongols.

Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

Founded by Kublai Khan, the Yuan Dynasty marked the first time China was ruled by a foreign power. The Yuan integrated China into the vast Mongol Empire, facilitating unprecedented cross-cultural exchange. While the dynasty maintained many aspects of Chinese governance, it faced resistance from the native population.

Yuan dynasty, c. 1290. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The decline of the Yuan was driven by internal rebellion and administrative inefficiency, leading to the rise of the Ming Dynasty.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

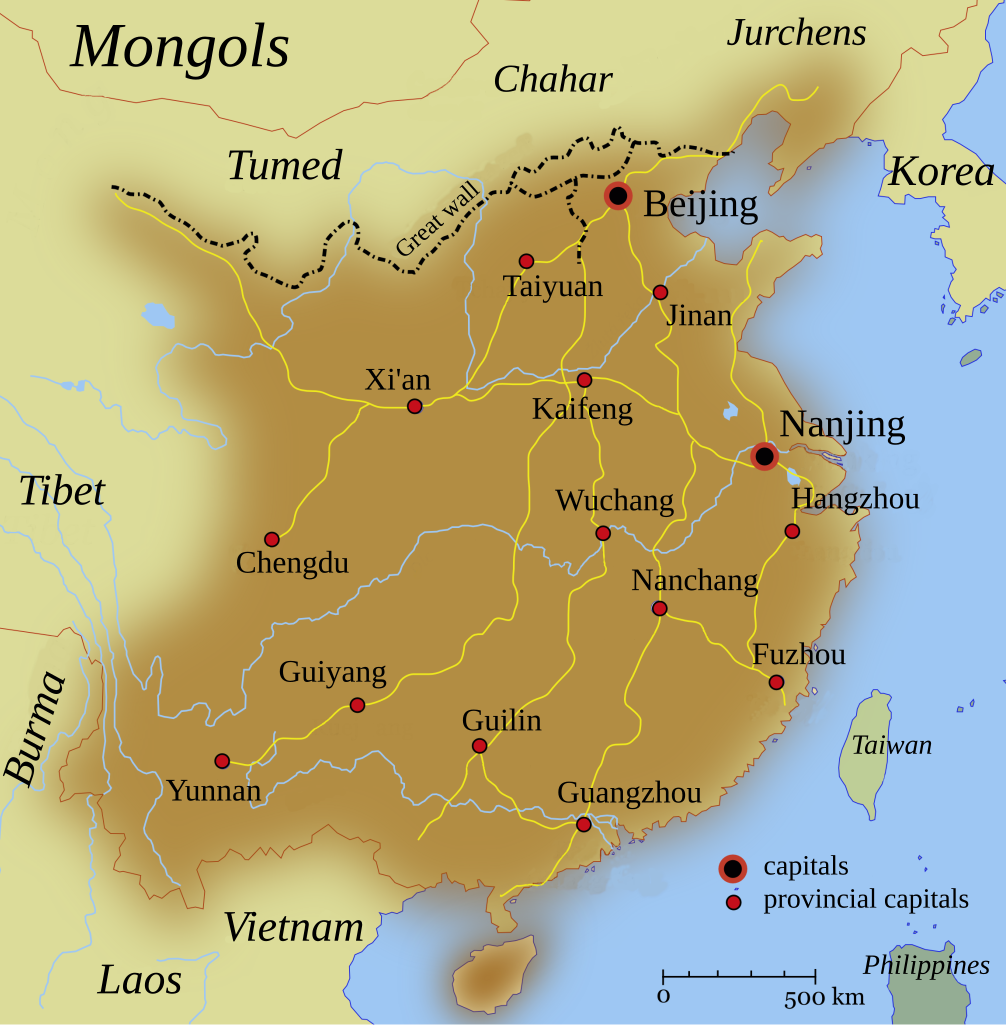

The Ming Dynasty restored native rule and implemented significant economic and cultural reforms. The early Ming period saw the construction of the Forbidden City and the voyages of Admiral Zheng He, who led large fleets to Southeast Asia, India, and East Africa.

Ming China around 1580. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

However, isolationist policies in the later Ming period curtailed maritime exploration. The dynasty eventually weakened due to corruption, economic difficulties, and internal strife, paving the way for the Qing Dynasty.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1912)

The Qing Dynasty, established by the Manchus, expanded China’s territory to its greatest extent. It maintained relative stability and prosperity during its early years but faced significant challenges in the 19th century, including the Opium Wars, internal rebellions, and increasing foreign influence.

Qing territory in 1911. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Efforts at modernization in the late Qing period, such as the Self-Strengthening Movement, were insufficient to prevent its decline. The fall of the Qing in 1912 marked the end of imperial rule in China and the beginning of the Republican era.

Republican era and Civil War (1912–1949)

The Republican era was marked by political fragmentation, warlordism, and the struggle between the Nationalists (Kuomintang) and the Communists. Japan’s invasion during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) further destabilized the country.

Following the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949), the Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong, established the People’s Republic of China on the mainland in 1949, while the Republic of China government continued to operate from Taiwan.

As of December 1949, the Chinese Communists had controlled the entire mainland China except Hainan, Taiwan and de facto country Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: Map of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Marked are administrative divisions and territorial disputes between the PRC and neighboring states. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Relief map of Taiwan from 1992. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Modern China: Reform and global influence (1949–present)

Under Mao’s leadership, the People’s Republic of China underwent significant political and social changes, including land reforms, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution. Following Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping implemented market-oriented reforms, leading to rapid economic growth and modernization.

Meanwhile, the Republic of China (Taiwan) focused on rebuilding its economy and establishing a democratic political system. Over the decades, Taiwan transformed into a highly developed society with significant technological and economic achievements.

In recent decades, the People’s Republic of China has emerged as a global superpower, with significant advancements in technology, infrastructure, and international influence. However, it continues to face challenges such as income inequality, environmental degradation, and geopolitical tensions.

Timeline summary

- ca. 5000 BCE – Early Neolithic cultures (Yangshao and Longshan)

- ca. 2070–1600 BCE – Xia Dynasty (semi-legendary)

- ca. 1600–1046 BCE – Shang Dynasty

- ca. 1046–256 BCE – Zhou Dynasty (Western and Eastern periods)

- Emergence of Confucianism (551–479 BCE)

- Emergence of Daoism (6th century BCE)

- Emergence of Legalism (475–221 BCE)

- 221–206 BCE – Qin Dynasty, first unification of China

- 206 BCE–220 CE – Han Dynasty, golden age

- Introduction of Buddhism (ca. 1st century CE)

- 220–280 CE – Three Kingdoms period

- 265–420 CE – Jin Dynasty (Western and Eastern)

- 581–618 CE – Sui Dynasty, reunification

- 618–907 CE – Tang Dynasty, cosmopolitan golden age

- 960–1279 CE – Song Dynasty, economic and cultural renaissance

- Rise of Neo-Confucianism (ca. 11th century CE)

- 1271–1368 CE – Yuan Dynasty, Mongol rule

- 1368–1644 CE – Ming Dynasty, restoration and exploration

- 1644–1912 CE – Qing Dynasty, last imperial dynasty

- 1949–present – Republic of China; since 1949, the Republic of China continues on Taiwan

- 1945–1949 – Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and Communists

- 1949–present – People’s Republic of China on the mainland

- 1950 – Invasion and annexation of Tibet by the People’s Liberation Army

Broader significance

The origins of Chinese civilization reveal a complex interplay of geography, resource management, and human innovation. From the early Neolithic cultures to the Zhou Dynasty, the evolution of Chinese society showcases the development of governance, writing, technology, and philosophy. These contributions not only shaped ancient China but also laid the groundwork for one of the longest continuous civilizations in human history.

Comparatively, like Mesopotamia and Egypt, Chinese civilization demonstrates how river systems fostered early agricultural societies and centralized political structures. In Mesopotamia, the first evident settlements appeared during the Ubaid period (5500–3700 BCE). Later, civilizations such as the Sumerians emerged around 3100 BCE in the fertile crescent, driven by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Similarly, Egyptian civilization began to flourish around 3100 BCE with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, centered on the predictable flooding of the Nile River. Chinese civilization, beginning with Neolithic cultures like the Yangshao around 5000 BCE and later evolving into the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, followed a parallel trajectory, rooted in the fertile lands of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers.

However, while Mesopotamian societies often formed city-states and Egypt emphasized centralized rule through divine kingship, China developed a unique blend of feudal governance and philosophical frameworks like Confucianism and Daoism that provided long-term cultural cohesion. The concept of the “Mandate of Heaven” in China parallels the divine authority in Egypt but carried a built-in mechanism for dynastic change, illustrating a distinctive approach to political legitimacy.

Understanding the origins of Chinese civilization, in the context of these global parallels, provides insight into the shared challenges and diverse solutions of early human societies while highlighting the unique trajectory of Chinese cultural and historical development.

References and further reading

- Li Liu, The Archaeology of Early China: From Prehistory to the Han Dynasty, 2015, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521196895

- K.C. Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China, 1987, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300037845

- Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy, The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC, 1999, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521470308

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey, The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1009151443

- John King Fairbank, China: A New History, 2006, Belknap Press, ISBN: 978-0674018280

- Mark Edward Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, 2010, The Belknap Press, ISBN: 978-0674057340

- William H. McNeill, The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, 1992, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226561417

- David N. Keightley, The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China, 2000, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-1557290700

- Jessica Rawson, Ancient China: Art and Archaeology, 1980, British Museum Press, ISBN: 978-0714114156

- Robert L. Thorp, China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization, 2005, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN: 978-0812239102

- Liu Li and Chen Xingcan, The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age, 2012, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0-521-64310-8

- Wikipedia article on the History of Chinaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Longshan cultureꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Shang dynastyꜛ

comments