Neidan and Waidan: Daoist alchemy and the pursuit of spiritual transformation

Daoist alchemy, a complex and multifaceted tradition, encompasses two primary branches: neidan (內丹), or internal alchemy, and waidan (外丹), or external alchemy. Both traditions share the ultimate goal of achieving harmony with the Dao and transcending the limitations of ordinary human existence, but they differ in their methods. While waidan involves the creation of elixirs from external substances, neidan focuses on internal processes of spiritual and physical transformation through meditation, breath control, and energy cultivation.

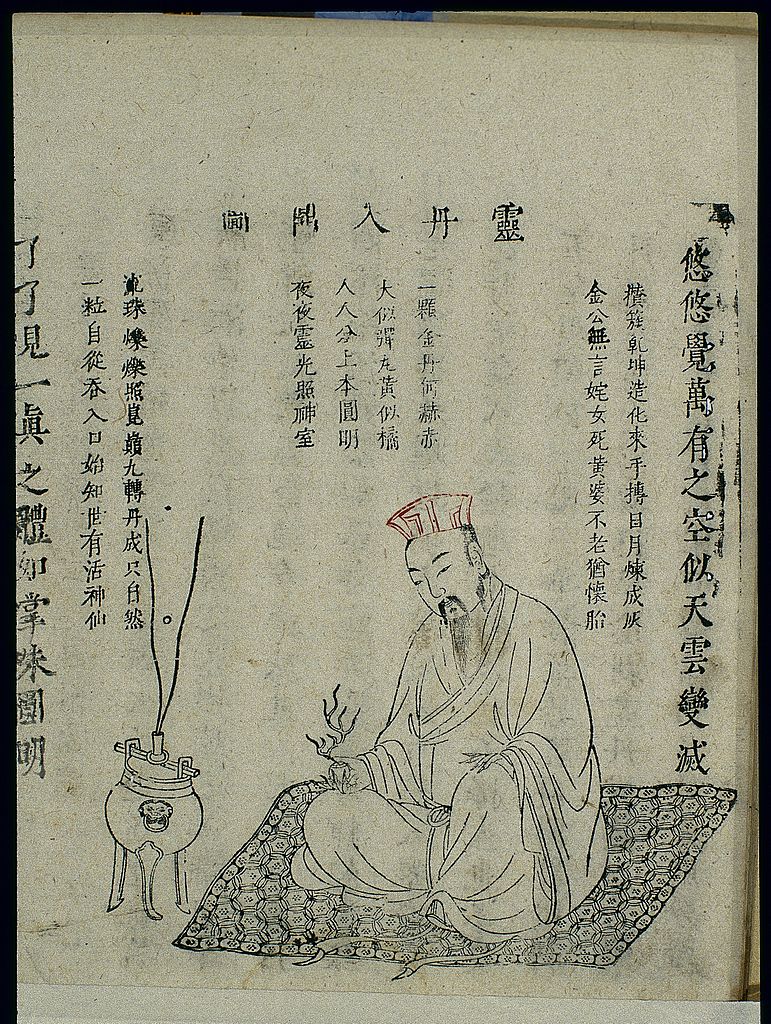

Chinese woodblock illustration of neidan “Cleansing the heart-mind and retiring into concealment”, 1615, Xingming guizhi (Principles of Inner Nature and Vital Force). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Philosophical foundations of Daoist alchemy

At the heart of Daoist alchemy lies the principle that the human being is a microcosm of the universe, and just as the cosmos undergoes cycles of transformation, so too can the human body and spirit. Both neidan and waidan are based on the belief that the Dao manifests in the form of Qi (vital energy) and that by refining and transforming Qi, one can achieve a higher state of being.

In both forms of alchemy, the ultimate goal is to return to a primordial state of unity with the Dao. This involves reversing the natural process of aging and death and achieving a state of spiritual immortality. The Daoist concept of immortality, however, is not merely physical but involves attaining a refined spiritual state in which one transcends ordinary existence and becomes one with the Dao.

Waidan: External alchemy

Waidan, or external alchemy, is the older of the two traditions, with its origins tracing back to the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE). Early Daoist practitioners sought to create elixirs of immortality by combining various minerals and metals, such as mercury, lead, sulfur, and gold. The belief was that by ingesting these elixirs, one could transform their internal Qi, prolong life, and ultimately achieve immortality.

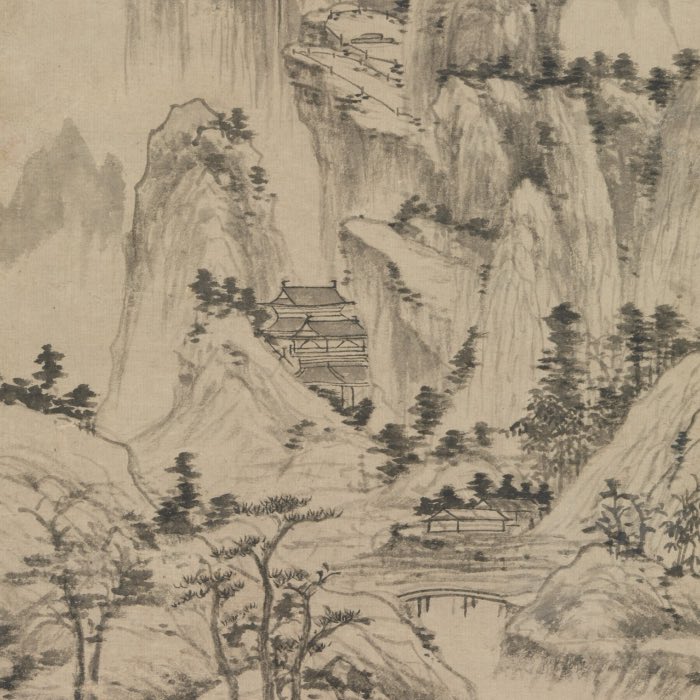

Chinese woodblock illustration of a waidan alchemical refining furnace, 1856, Waike tushuo 外科圖説 (Illustrated Manual of External Medicine). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

During the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), waidan practices became more systematized and closely associated with Daoist religious traditions. Numerous texts from this period describe detailed alchemical recipes and procedures, as well as the spiritual goals of alchemy. The pursuit of external alchemy continued through the Tang and Song dynasties, though it gradually gave way to the more introspective practices of neidan.

A late Shang-era (13th–11th century BCE) bronze ritual ding (bronze vessel) with taotie (monster mask) motif. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Philosophical and practical aspects

In waidan, the process of creating an elixir involves heating and refining substances in a crucible, symbolizing the cosmic process of transformation. The alchemical furnace and crucible are often metaphorically linked to the human body, and the external elixir represents the refinement of Qi within the practitioner.

Although waidan was primarily concerned with physical substances, it was never merely a material process. The alchemical work was accompanied by meditative practices and rituals aimed at attuning the practitioner to the Dao. The external elixir was believed to act as a catalyst for internal transformation, enhancing the practitioner’s vitality and spiritual awareness.

Despite its spiritual aspirations, waidan was not without risks. Many practitioners suffered from mercury and lead poisoning due to the toxic nature of the substances used. Over time, these dangers, along with philosophical shifts toward internal processes, led to the decline of waidan and the rise of neidan.

Neidan: Internal alchemy

Neidan, or internal alchemy, emerged as a response to the limitations and dangers of external alchemy. Its origins can be traced to the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), though it reached its peak during the Song (960–1279 CE) and Yuan (1271–1368 CE) dynasties. Prominent figures in the development of neidan include Lu Dongbin and Zhang Boduan, who are traditionally regarded as patriarchs of the practice.

Development of the So-called immortal embryo in the lower dantian of the Daoist cultivator. The immortal embryo is the result of the alchemical process of internal alchemy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Unlike waidan, neidan focuses on internal processes of transformation, with the human body serving as the alchemical furnace. The goal is to refine the practitioner’s Qi, transform it into a more subtle and spiritual form, and ultimately achieve union with the Dao. This process is metaphorically described using alchemical terms such as the “elixir”, “furnace”, and “crucible”, but these refer to internal energies and spiritual states rather than physical substances.

Chinese woodblock illustration of neidan “Putting the miraculous elixir on the ding tripod”, 1615 Xingming guizhi (Principles of Inner Nature and Vital Force). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Philosophical and practical aspects

In neidan, the practitioner seeks to refine three essential elements:

- Jing (精): Essence, associated with physical vitality and reproductive energy.

- Qi (氣): Vital energy, which sustains life and connects the body and mind.

- Shen (神): Spirit or consciousness, representing the highest and most refined aspect of the self.

The alchemical process involves transforming Jing into Qi, Qi into Shen, and ultimately refining Shen into the Dao. This process is often described in three stages:

- Lian Jing Hua Qi (煉精化氣): Refining essence into vital energy.

- Lian Qi Hua Shen (煉氣化神): Refining vital energy into spirit.

- Lian Shen He Dao (煉神合道): Refining spirit into union with the Dao.

The practice of neidan involves a combination of meditation, breath control, visualization, and physical exercises. These practices are designed to harmonize the body and mind, cultivate Qi, and guide it through specific pathways (meridians) within the body. Advanced practitioners aim to create an internal “elixir” that symbolizes the attainment of spiritual immortality.

Neidan and Waidan: A comparative perspective

While neidan and waidan differ in their methods, they share common philosophical foundations. Both traditions emphasize the transformation of Qi and the attainment of immortality, understood not as mere physical longevity but as a state of spiritual unity with the Dao.

However, neidan represents a shift from external, material processes to internal, spiritual ones. This shift reflects a broader trend in Daoist thought toward introspection and self-cultivation. Whereas waidan seeks to manipulate external substances to effect internal change, neidan focuses entirely on internal energies and their refinement.

Despite the decline of waidan as a formal practice, its symbolic language and metaphors continue to be used in neidan texts. The imagery of the furnace, crucible, and elixir remains central to internal alchemy, serving as a bridge between the external and internal traditions.

Influence on Chinese culture and spirituality

Daoist alchemy, both internal and external, has had a profound influence on Chinese culture and spirituality. Its ideas have permeated traditional Chinese medicine, martial arts, and meditation practices, shaping the development of disciplines such as Qigong and Tai Chi.

In addition, Daoist alchemy has influenced other spiritual traditions, including Chinese Buddhism, particularly the Chan (Zen) school. The emphasis on internal cultivation and spiritual transformation in neidan resonates with Buddhist practices of meditation and enlightenment.

Conclusion

Neidan and waidan represent two complementary approaches to Daoist alchemy, both aiming at the ultimate goal of spiritual transformation and union with the Dao. While waidan focuses on external substances and their refinement, neidan emphasizes internal processes of cultivating Qi and transforming consciousness. Together, these traditions reflect the richness and depth of Daoist philosophy, offering a holistic vision of the human being as a microcosm of the universe.

References

- Slingerland, Edward, Effortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195314878

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing - , Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

comments