The Mycenaean civilization

The Mycenaean civilization, flourishing from approximately 1600 BCE to 1100 BCE, represents one of the earliest advanced societies of mainland Greece. Known for its fortified palace centers, Linear B script, and rich burial practices, the Mycenaeans played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural and political landscape of the Aegean and influencing the development of later Greek civilization. Their interactions with neighboring cultures, such as the Minoans, Mesopotamians, and Egyptians, underscore their significance in the broader narrative of the Bronze Age.

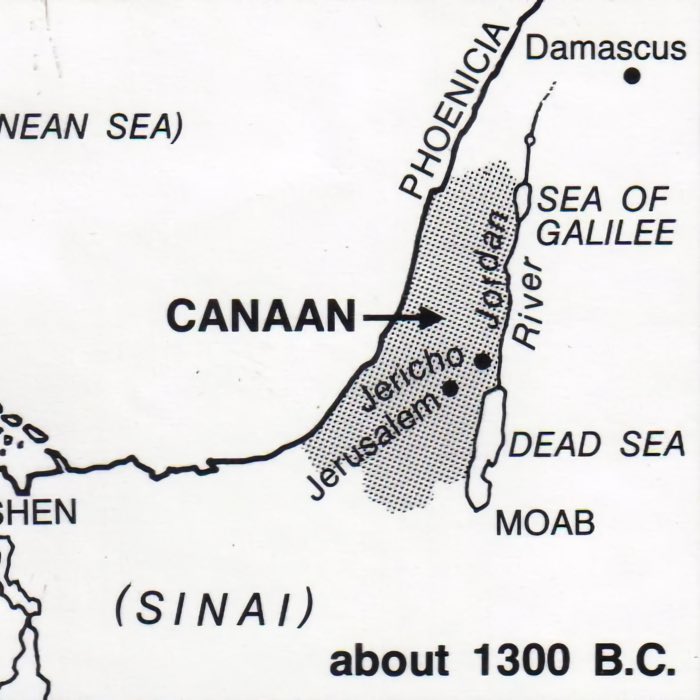

Map of Mycenaean Greece 1400-1200 BCE. Palaces, main cities and other settlements are indicated. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Origins and early development

The Mycenaean civilization emerged in the Late Bronze Age, building upon the traditions of earlier Greek cultures while integrating influences from the Minoans and other Mediterranean societies. These early communities were initially agrarian, relying on farming and local resources. However, the establishment of palatial centers such as Mycenae, Pylos, and Tiryns marked a significant transformation, ushering in a centralized and hierarchical society characterized by increased complexity and organization.

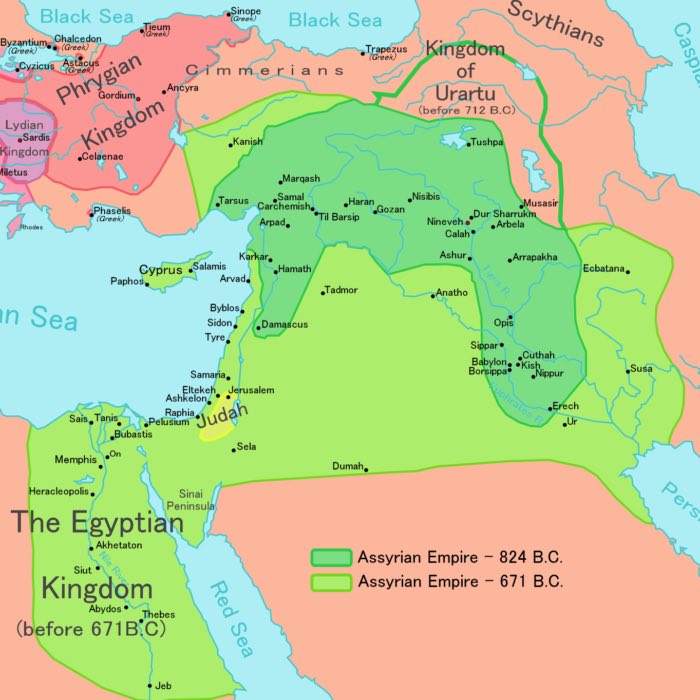

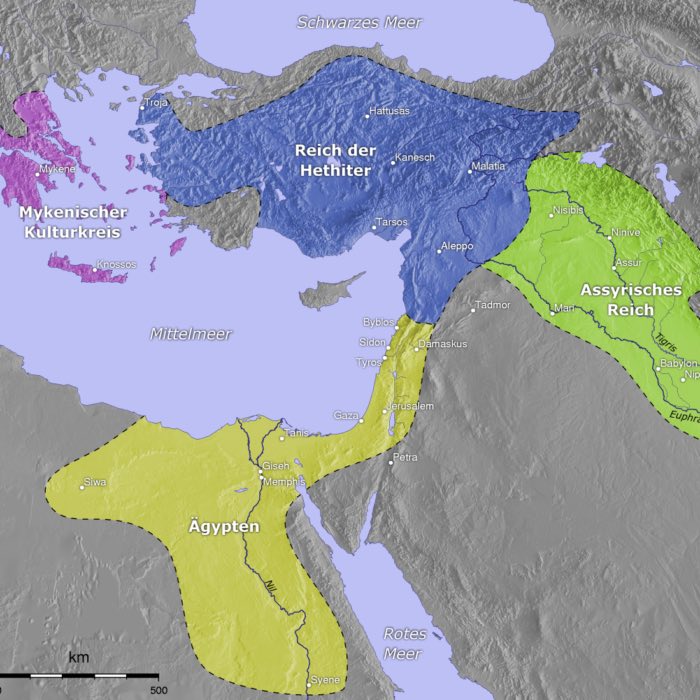

Mediterranean, Mesopotamian and Egypt civilizations around 1230/20 BCE, with the Hittite Empire in blue, Egypt in yellow, the Assyrian Empire in green – and the Mykenaean civilization in purple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Mediterranean, Mesopotamian and Egypt civilizations around 1230/20 BCE, with the Hittite Empire in blue, Egypt in yellow, the Assyrian Empire in green – and the Mykenaean civilization in purple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Reconstruction of the political landscape in c. 1400–1250 BCE mainland southern Greece. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Example of a palace floor plan: Tiryns, map of the palace and the surrounding fortification. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of a palace floor plan: Tiryns, map of the palace and the surrounding fortification. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The adoption of Minoan cultural elements, including their art, architectural techniques, and religious practices, played a pivotal role in shaping the Mycenaeans’ development. Minoan fresco styles, marine motifs, and ceremonial practices were adapted and reinterpreted to suit the Mycenaean emphasis on power and authority. The Mycenaeans, however, distinguished themselves through their militaristic nature, which was evident in their heavily fortified citadels, such as the imposing walls of Mycenae and Tiryns, built using “Cyclopean” masonry techniques. The iconic Lion Gate at Mycenae exemplifies their architectural prowess and served as both a symbol of power and a defensive feature.

The Lion Gate at Mycenae. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Burial practices also reflected their hierarchical and martial culture. Richly adorned shaft graves, such as those in Grave Circle A at Mycenae, contained weapons, gold masks, and intricate jewelry, signifying the wealth and status of the elite. These graves not only highlight the Mycenaeans’ social stratification but also their belief in an afterlife where material goods accompanied the deceased. These practices reveal the integration of martial values into their cultural and spiritual life, underscoring their distinct identity within the Bronze Age Aegean world.

Cultural achievements and society

The Mycenaeans are renowned for their administrative and cultural accomplishments. The use of Linear B, an early form of Greek writing adapted from the Minoan Linear A script, allowed for efficient record-keeping and the management of resources. Administrative tablets reveal details about taxation, trade, and religious offerings, highlighting the complexity of Mycenaean society.

Linear B tablets (Mycenaean Greek). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Art and craftsmanship flourished in Mycenaean Greece. Frescoes, pottery, and goldwork, such as the famous Mask of Agamemnon, demonstrate their artistic sophistication and connections to other Mediterranean cultures. Mycenaean pottery, often decorated with marine and geometric motifs, was widely traded, indicating their integration into regional economic networks.

Left: Warrior wearing a boar’s tusk helmet, from a Mycenaean chamber tomb in the Acropolis of Athens, 14th–13th century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Death mask, known as the Mask of Agamemnon, Grave Circle A, Mycenae, 16th century BCE, probably the most famous artifact of Mycenaean Greece. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Socially, the Mycenaeans were organized into a strict hierarchy. The wanax, or king, presided over palace administration, supported by a network of officials and scribes. Beneath this elite class were artisans, merchants, and farmers who sustained the economy. The emphasis on martial prowess is evident in their burial practices, which included richly adorned tombs for warriors, such as the tholos or “beehive” tombs.

Trade and external relations

The Mycenaean civilization thrived on extensive trade networks that connected the Aegean with the wider Mediterranean and Near East. They exported goods such as olive oil, wine, and pottery, and imported precious metals, ivory, and exotic items from Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant. Evidence of Mycenaean pottery in sites as distant as Cyprus and Anatolia attests to their expansive trade reach.

Left: Reconstruction of a Mycenaean ship. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Mycenaean palace amphora, found in the Argolid. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Interaction with the Minoan civilization was particularly influential. While the Mycenaeans initially adopted Minoan art and religious practices, they eventually dominated Crete around 1450 BCE, integrating Minoan elements into their own culture. The influence of Egyptian and Mesopotamian motifs in Mycenaean art and architecture suggests direct or indirect contact through trade or diplomatic exchanges.

Comparison with Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Minoan civilization

The Mycenaean civilization shares both similarities and distinctions with Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Minoan civilization. Like Mesopotamian city-states, Mycenaean palace centers served as administrative and economic hubs, supported by a hierarchical society. However, unlike the extensive urbanization of Mesopotamia, Mycenaean settlements were more scattered and centered around fortified citadels, reflecting their militaristic focus.

Egyptian influence is evident in Mycenaean art and burial practices, particularly the use of gold and the construction of monumental tombs. However, while Egypt centralized power under divine kingship, Mycenaean rulers derived authority from their role as warrior-leaders, emphasizing military strength over divine association.

The Minoans, who preceded the Mycenaeans in the Aegean, were a major source of inspiration. The Mycenaeans adopted Minoan technologies, administrative systems, and religious motifs but adapted them to suit their more hierarchical and militaristic society. Unlike the relatively peaceful and trade-oriented Minoans, the Mycenaeans were expansionist, as demonstrated by their conquest of Crete and their role in the Trojan War, as described in later Greek mythology.

Decline and legacy

The decline of the Mycenaean civilization began around 1200 BCE, coinciding with widespread disruptions in the Eastern Mediterranean, often attributed to the “Sea Peoples” and internal strife. Palatial centers were abandoned, and Linear B writing disappeared, marking the end of the Bronze Age in Greece.

Marching soldiers on the Warrior Vase, c. 1200 BCE, a krater from Mycenae. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Marching soldiers on the Warrior Vase, c. 1200 BCE, a krater from Mycenae. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

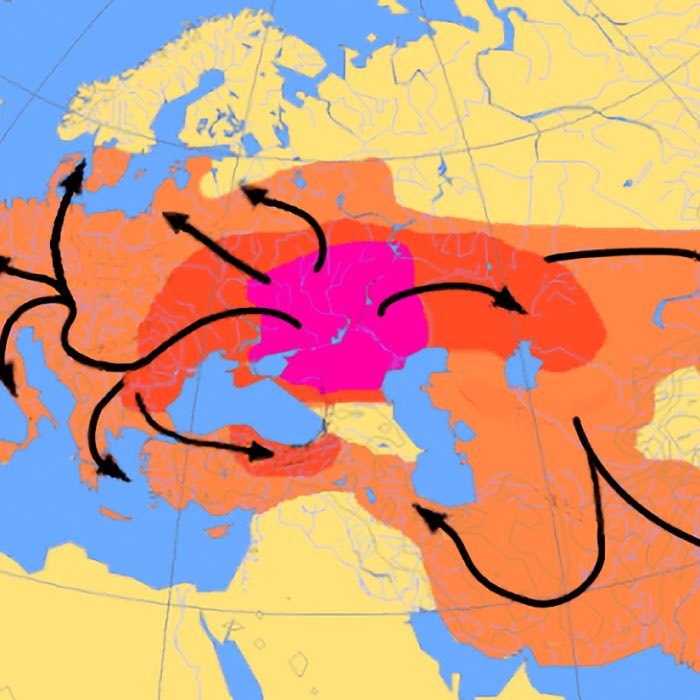

Invasions, destructions and possible population movements during the collapse of the Bronze Age, c. 1200 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Invasions, destructions and possible population movements during the collapse of the Bronze Age, c. 1200 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Despite their decline, the Mycenaeans left an enduring legacy. Their myths and legends, preserved in the Homeric epics The Iliad and The Odyssey, became foundational to Greek identity and literature. The architectural and artistic achievements of the Mycenaeans influenced later Greek city-states, bridging the gap between the Bronze Age and the classical era.

References

- Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 2015, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1107503410

- Cynthia W. Shelmerdine (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521891271

- Louise Schofield, The Mycenaeans, 2007, British Museum Press, ISBN: 978-0714120904

- Oliver Dickinson, The Aegean Bronze Age, 1994, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521456647

- Nancy Demand, The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History, 2012, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405155519

- Rodney Castleden, The Mycenaeans, 2005, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415363365

- John Chadwick, The Mycenaean World, 1976, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521290371

- Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed, 2021, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691208015

- Sarah P. Morris, Daidalos and the Origins of Greek Art, 1995, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691001609

- Peter Warren and Vronwy Hankey, Aegean Bronze Age Chronology, 1989, Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd, 978-0906515679

comments