Mokṣa: Liberation in Hindu philosophy

Mokṣa, derived from the Sanskrit root “muc” (to release), signifies liberation or freedom from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra). It represents the highest spiritual goal in Hindu philosophy, marking the end of suffering and the realization of one’s true nature. Unlike material or worldly goals, mokṣa is considered a transcendent state beyond time, space, and causality, often described as the direct experience of unity with the ultimate reality (brahman). In this post, we explore the origins, philosophical interpretations, and different paths to mokṣa in Hindu traditions.

Mokṣa, interpreted by DALL•E, “using a single continuous line to evoke liberation and transcendence”.

The origins of mokṣa

The concept of mokṣa developed during the Upanishadic period (circa 800–300 BCE), when Indian philosophical thought shifted its focus from ritualistic practices to questions about the nature of existence, the self (ātman), and ultimate reality (brahman). Early Vedic texts primarily emphasized worldly prosperity (artha) and pleasure (kāma) as life goals, but the Upanishads introduced the idea of liberation as the supreme objective.

In texts like the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad and Chāndogya Upanishad, mokṣa is described as the realization of the unity of ātman) and brahman. This realization leads to the dissolution of ignorance (avidyā) and the cessation of desire, which are seen as the causes of bondage to samsāra.

Mokṣa and the four puruṣārthas

In Hindu philosophy, mokṣa is one of the four puruṣārthas (goals of human life):

- Dharma: Righteous duty and moral order.

- Artha: Material wealth and prosperity.

- Kāma: Pleasure and desire.

- Mokṣa: Liberation and spiritual freedom.

While dharma, artha, and kāma pertain to life in the world, mokṣa transcends worldly concerns. The pursuit of mokṣa is considered the ultimate purpose of human existence, with the other goals serving as preparatory stages for spiritual liberation.

Philosophical interpretations of mokṣa

Different schools of Hindu philosophy offer varying interpretations of mokṣa, reflecting their distinct metaphysical views:

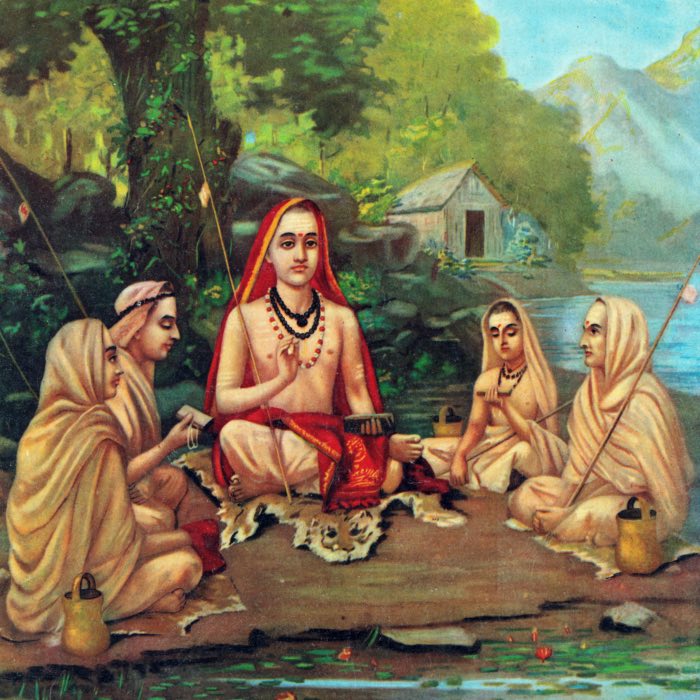

Advaita Vedanta: Mokṣa as realization of non-duality

In Advaita Vedanta, as expounded by Ādi Śaṅkara, mokṣa is the realization of the non-dual nature of ātman) and brahman. According to Advaita:

- Ignorance as the cause of bondage: Bondage to samsāra arises from ignorance (avidyā) of one’s true nature. Liberation involves the removal of ignorance through self-knowledge (jñāna).

- Identity of ātman) and brahman: Mokṣa is attained when one directly experiences that ātman) (the self) is identical to brahman (the ultimate reality). This realization destroys the illusion of individuality and duality.

- State of freedom: The liberated person (jīvanmukta) continues to live in the world but remains unaffected by it, having transcended the cycle of birth and death.

Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta: Mokṣa as union with brahman

In Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta, Rāmānuja describes mokṣa as a state of eternal union with brahman, who is identified with the personal God Viṣṇu. Key features of this interpretation include:

- Devotion and grace: Liberation is achieved through loving devotion (bhakti) to Viṣṇu and reliance on His grace.

- Real but dependent self: Unlike Advaita, Viśiṣṭādvaita maintains that the self retains its individuality even after liberation, though it exists in eternal communion with brahman.

- Blissful service: The liberated soul enjoys eternal bliss in the presence of Viṣṇu and engages in His service.

Dvaita Vedanta: Mokṣa as eternal proximity to God

In Dvaita Vedanta, Madhva asserts that mokṣa involves eternal proximity to brahman, who is identified with Viṣṇu, but without any form of identity or merger:

- Eternal distinction: The self and brahman are eternally distinct. Liberation does not erase this distinction but brings the self into the blissful presence of Viṣṇu.

- Devotion and moral conduct: Liberation is attained through unwavering devotion (bhakti) and moral conduct, guided by scriptural injunctions.

- Hierarchy of liberated souls: Madhva proposes that liberated souls may occupy different positions of proximity to Viṣṇu, reflecting their spiritual status.

Paths to mokṣa

Hindu philosophy recognizes multiple paths (mārgas) to mokṣa, accommodating different temperaments and capacities:

- Jñāna yoga (path of knowledge)

- Central to Advaita Vedanta, this path involves self-inquiry (ātma-vicāra) and meditation on the nature of ātman) and brahman. Through knowledge (jñāna), one overcomes ignorance and realizes non-duality.

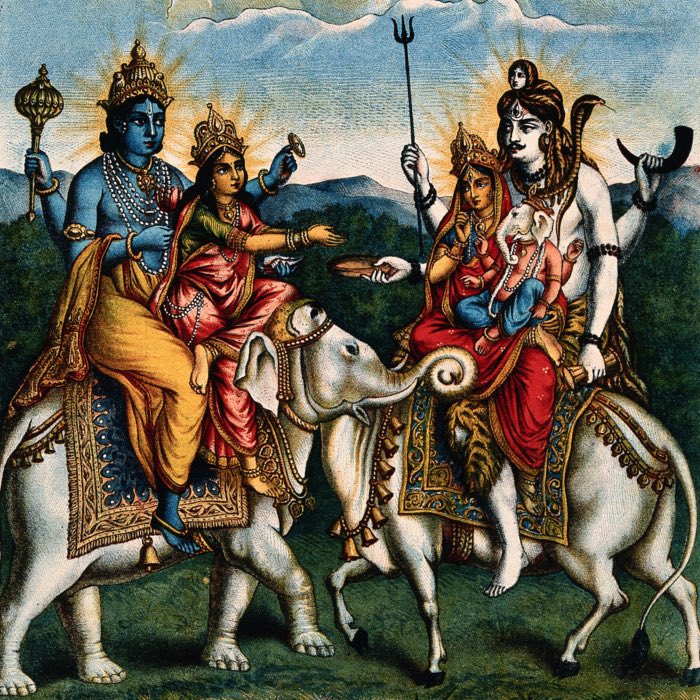

- Bhakti yoga (path of devotion)

- Popular in devotional traditions, this path emphasizes surrender to a personal deity, such as Viṣṇu or Śiva. Devotional practices include prayer, chanting, and ritual worship, culminating in the experience of divine grace and liberation.

- Karma yoga (path of selfless action)

- Taught in the Bhagavad Gītā, karma yoga involves performing one’s duties without attachment to the results. By renouncing the fruits of action, individuals prevent the accumulation of new karma and gradually attain liberation.

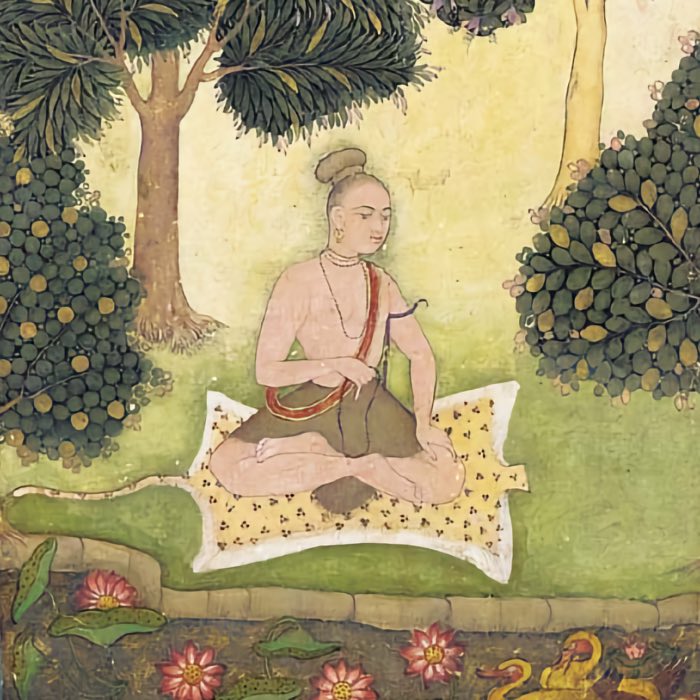

- Rāja yoga (path of meditation)

- Described in Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras, this path focuses on disciplined meditation (dhyāna) and control of the mind (citta-vṛtti nirodha) to achieve self-realization and freedom from samsāra.

Characteristics of the liberated person (jīvanmukta)

In Advaita Vedanta, a person who has attained mokṣa while still living is known as a jīvanmukta (“liberated while alive”). The jīvanmukta is characterized by:

- Freedom from desire and attachment: Having realized the illusory nature of the world, the jīvanmukta remains unaffected by worldly pleasures and sorrows.

- Equanimity: The liberated person maintains equanimity in all situations, recognizing the unity of all existence.

- Compassion and ethical conduct: Though free from personal desires, the jīvanmukta acts out of compassion for others, engaging in selfless service.

Upon the death of a jīvanmukta, they achieve videhamukti (“liberation without a body”), where the self is completely freed from the cycle of birth and death.

Conclusion

Mokṣa represents the ultimate goal of human life in Hindu philosophy, signifying freedom from the cycle of samsāra and the realization of one’s true nature. While different schools of thought offer distinct interpretations of liberation, they all emphasize that mokṣa is attained through the dissolution of ignorance, desire, and attachment. By understanding and practicing the various paths to liberation, individuals can transcend the limitations of worldly existence and attain eternal peace and bliss.

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- Eliot Deutsch, Advaita Vedanta: A philosophical reconstruction, 1969, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824802714

- Eknath Easwaran (translator), Bhagavad Gītā, 2012, Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 978-3442220137

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

comments