The Maya civilization

The Maya civilization, which flourished between approximately 2000 BCE and 1500 CE, represents one of the most sophisticated and enduring cultures of the ancient Americas. Centered in the tropical lowlands of present-day Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, and southern Mexico, the Maya are renowned for their achievements in writing, astronomy, mathematics, and monumental architecture. The civilization’s intricate socio-political structures and vibrant cultural traditions continue to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

The Maya area within in the broader Mesoamerican region. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Origins and early development

The roots of Maya civilization trace back to the Preclassic period (ca. 2000 BCE–250 CE), during which early agricultural communities began to emerge in the fertile regions of Mesoamerica. These communities cultivated staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, forming the economic foundation of Maya society. Early ceremonial centers, such as Nakbé and El Mirador, featured monumental architecture, signaling the rise of complex social hierarchies and religious practices.

Mayan city-states during the Classic period. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Olmec civilization, which preceded the Maya, played a significant role in shaping early Maya development. Shared cultural elements, including ritual practices, iconography, and possibly early writing systems, suggest a degree of continuity and influence between these cultures. By the Late Preclassic period, the Maya had begun to establish their unique identity, marked by advancements in urban planning and the construction of monumental pyramids.

El Castillo, at Chichen Itza. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cultural achievements and society

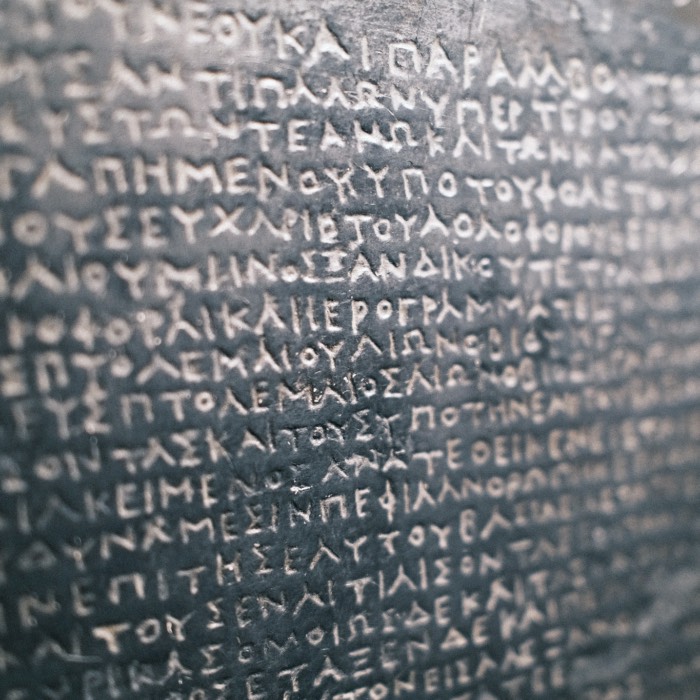

The Maya civilization is perhaps best known for its writing system, the most advanced in the pre-Columbian Americas. The Maya developed a complex hieroglyphic script used for recording historical events, religious texts, and administrative matters. These inscriptions, often carved on stelae and temple walls, provide invaluable insights into Maya history and culture.

Chichen Itza was the most important city in the northern Maya region. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Reconstruction of the urban core of Tikal in the 8th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Astronomy and mathematics were central to Maya society. The Maya developed a sophisticated calendar system based on precise astronomical observations, including the Long Count calendar, which tracked cycles spanning thousands of years. Their understanding of zero and advanced arithmetic enabled complex calculations, supporting their architectural and astronomical endeavors.

Left: Stela from Toniná, representing the 6th-century king Bahlam Yaxuun Tihl. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Classic period sculpture showing sajal Aj Chak Maax presenting captives before ruler Itzamnaaj Bʼalam III of Yaxchilan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

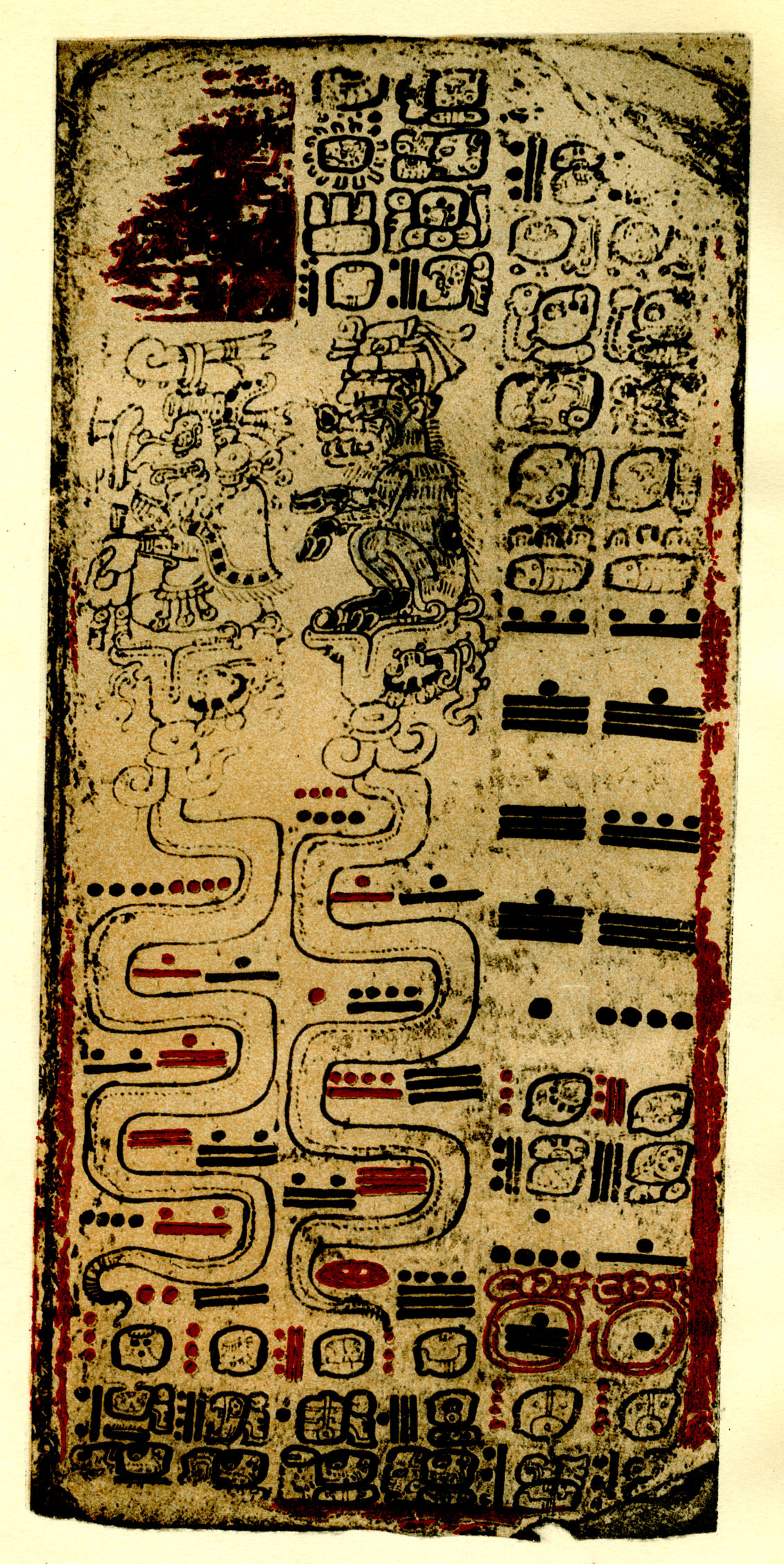

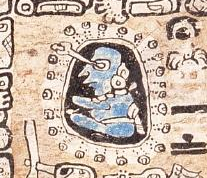

Left: Maya numerals on a page of the Postclassic Dresden Codex. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Representation of an astronomer from the Madrid Codex. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The social structure of the Maya was hierarchical, with a divine king (ajaw) at the apex, supported by an elite class of nobles, priests, and scribes. Below them were artisans, merchants, and farmers who sustained the economic and cultural vitality of Maya cities. The construction of monumental centers such as Tikal, Copán, and Palenque underscored the power and wealth of Maya rulers, while smaller settlements supported regional economies and cultural cohesion.

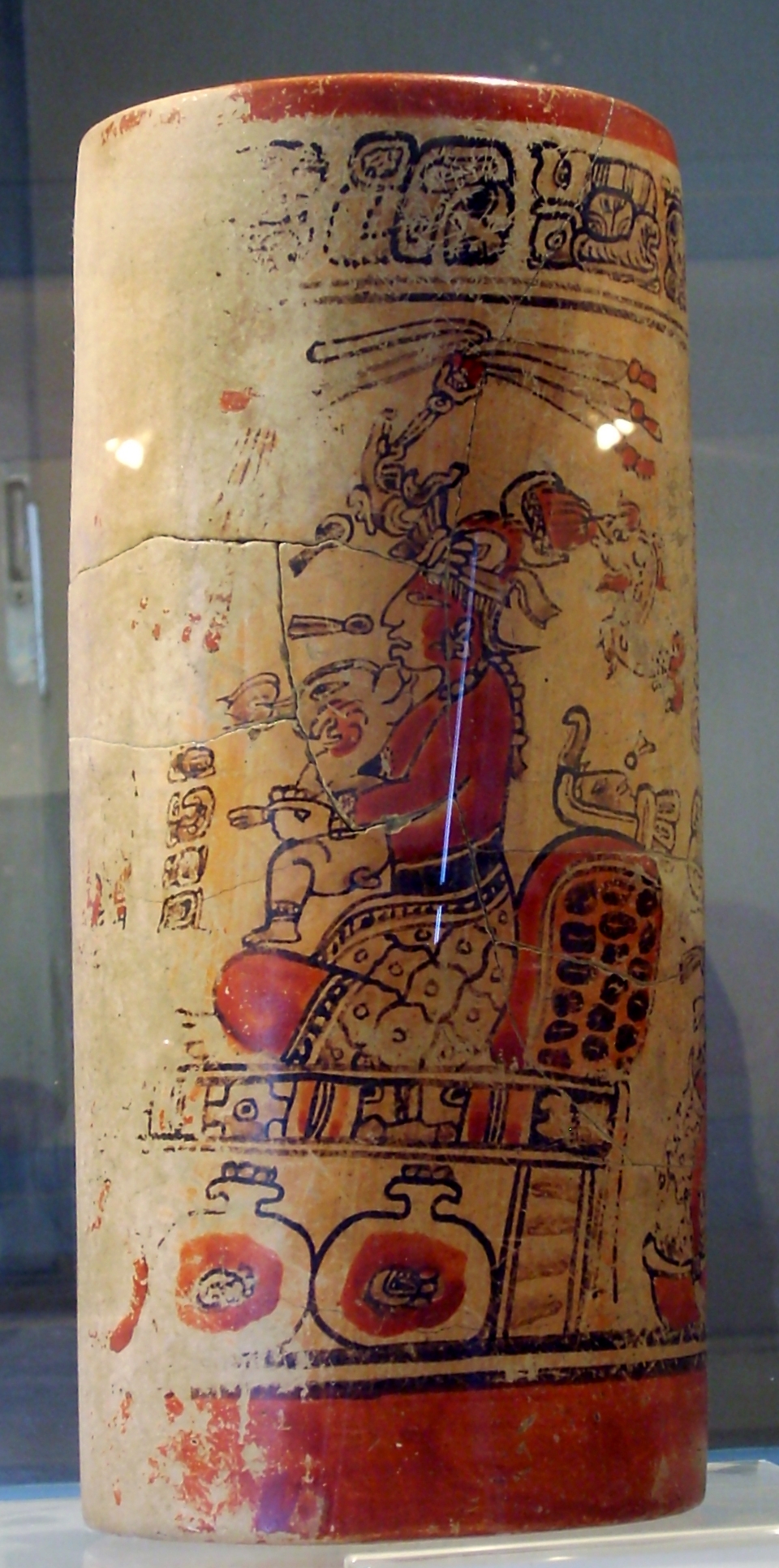

Left: Jaina Island figurine representing a Classic period warrior, late Classic Period, c. 550-950 CE, ceramic and paint. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0) – Right: Painted ceramic vessel from Sacul. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Religious rractices and cosmology

Religion permeated every aspect of Maya life, influencing governance, art, and science. The Maya pantheon included gods associated with natural elements, celestial bodies, and human activities. Ritual practices often involved offerings, bloodletting, and human sacrifice, intended to maintain cosmic balance and appease the gods.

Jade funerary mask of king Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Maya cosmology emphasized the cyclical nature of time and the interconnectedness of the earthly, celestial, and underworld realms. Ceremonial centers and pyramids often aligned with astronomical phenomena, reflecting the integration of spiritual beliefs and scientific observation.

Temple of the Great Jaguar, at Tikal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Relief sculpture of a decapitated ballplayer, adorning the Great Ballcourt at Chichen Itza. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Trade and regional influence

The Maya civilization was a hub of trade and cultural exchange within Mesoamerica. Their trade networks connected them to neighboring regions, facilitating the exchange of goods such as jade, obsidian, cacao, and textiles. This economic interconnectivity enriched Maya society and disseminated their cultural and technological innovations.

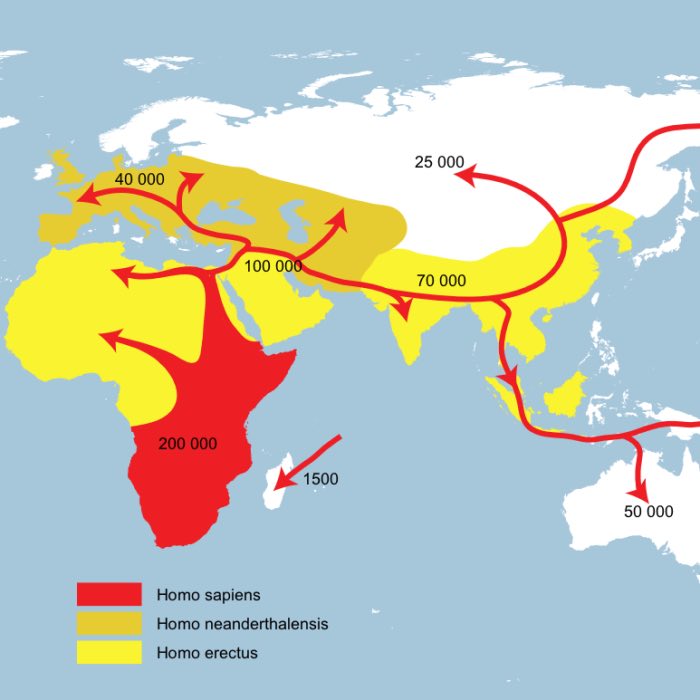

Map of Mayan language migration routes. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The influence of the Maya extended beyond their immediate geographic boundaries. Elements of Maya art, architecture, and iconography can be seen in neighboring cultures, while their intellectual achievements, such as the calendar and hieroglyphic writing, shaped the broader Mesoamerican cultural sphere.

Maya script on Cancuén Panel 3 describes the installation of two vassals at Machaquilá by Cancuén king Taj Chan Ahk. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Ceramic vessel painted with Maya script. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

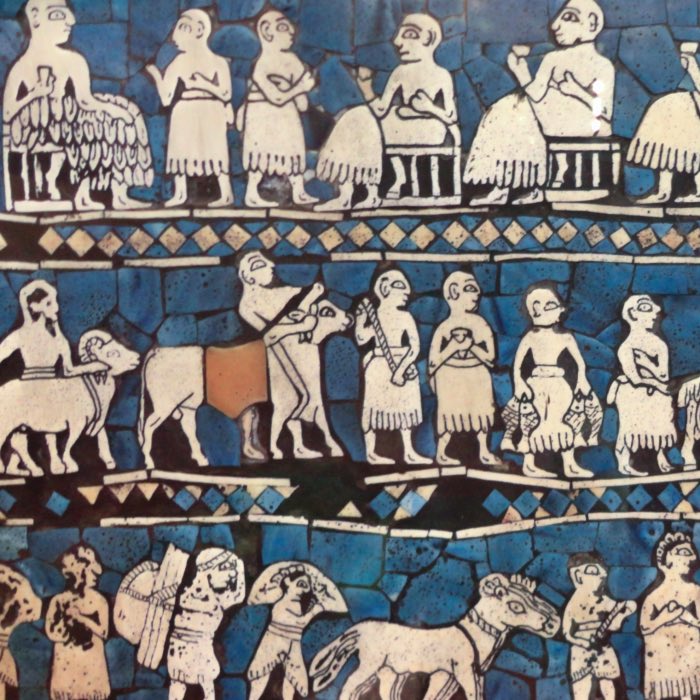

Comparisons with other civilizations

The Maya civilization demonstrates how human ingenuity shaped advanced societies in diverse environments. Their mastery of hieroglyphic writing, intricate calendar systems, and monumental architecture reflects a global trend seen in ancient civilizations, yet their achievements stand out for their regional specificity. Unlike cultures that emerged along great river systems, the Maya adapted to tropical lowlands through innovative agricultural techniques, including raised fields and terracing.

Building on the cultural foundations of the Olmecs, the Maya expanded Mesoamerican traditions in profound ways. Their hieroglyphic writing system, astronomical observations, and complex urban centers like Tikal and Calakmul became hallmarks of their civilization. While their contemporaries in the Andes, such as the Moche, emphasized irrigation and metallurgy, the Maya excelled in recording historical narratives and astronomical data, leaving a detailed legacy unmatched in pre-Columbian America.

The Maya’s regional diversity and dynamic city-states distinguish them globally. Their resilience in adapting to challenging environments and their deep integration of scientific and spiritual traditions make them a defining civilization in world history.

Decline and Legacy

The decline of the Maya civilization was a gradual process influenced by environmental stress, resource depletion, and political instability. By the end of the Postclassic period (ca. 1500 CE), many major centers had been abandoned, though some regions continued to thrive under Spanish colonial influence.

Calakmul was one of the most important Classic period cities. Today, it is burried in the jungle, but its pyramids are still visible. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Despite their decline, the Maya left an indelible legacy. Their contributions to writing, astronomy, and art continue to be celebrated and studied, while modern Maya communities maintain cultural traditions that connect them to their ancient heritage.

References

- Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston, The Maya, 2022, Thames & Hudson, ISBN: 978-0500295144

- David Drew, The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings, 2000, Orion Publishing Co, ISBN: 978-0753809891

- Linda Schele and Mary Ellen Miller, The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art, 1986, George Braziller, ISBN: 978-0807611593

- Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya, 2000, Thames & Hudson, ISBN: 978-0500051030

- John S. Henderson, The World of the Ancient Maya, 1997, Cornell University Press, ISBN: 978-0801431838

- Joyce Marcus, Mesoamerican Writing Systems: Propaganda, Myth, and History in Four Ancient Civilizations, 1992, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691094748

- Arthur Demarest, Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521533904

- Takeshi Inomata and Stephen D. Houston (Eds.), Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya: Data and Case Studies, 2018, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0813338804

- Nikolai Grube (Ed.), The Maya: Voices in Stone, 1016, Turner Publicaciones, S.L., ISBN: 978-8416354870

- Prudence M. Rice, Maya Political Science: Time, Astronomy, and the Cosmos, 2004, University of Texas Press, ISBN: 978-0292705692

comments