Māyā: The concept of the illusion of reality in Hindu philosophy

In Hindu philosophy, the concept of māyā refers to the illusory nature of the empirical world and the mistaken perception of duality. Derived from the Sanskrit root “mā” (to measure or create), māyā originally signified magic or supernatural power. Over time, it evolved into a sophisticated metaphysical and epistemological concept, central to Vedantic philosophy. Primarily discussed in the Upanishads and developed extensively in the Vedanta schools, māyā explains the apparent multiplicity of the universe and the ignorance (avidyā) that obscures the true nature of reality. This post explores the origins, philosophical interpretations, and implications of māyā in the quest for liberation (mokṣa).

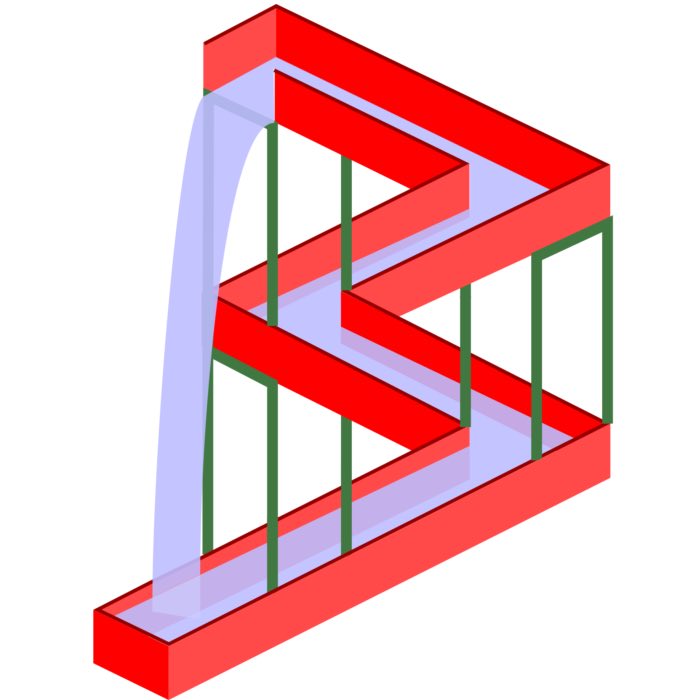

M. C. Escher paintings such as the Waterfall – redrawn in this sketch – demonstrates the Hindu concept of māyā. The impression of water flow the sketch gives is in reality not what it seems. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The origins of māyā

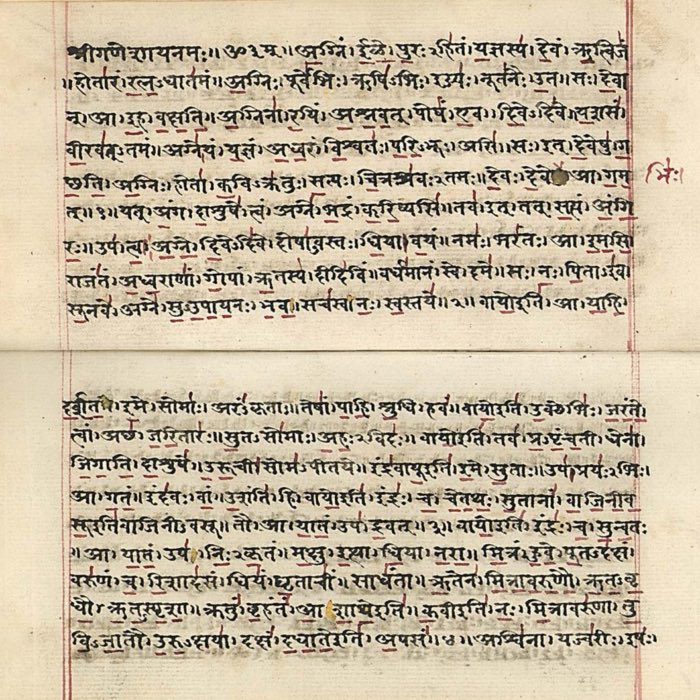

The earliest mentions of māyā can be found in the Rigveda. In Hindu philosophy, the concept of māyā refers to the illusory nature of the empirical world and the mistaken perception of duality. Derived from the Sanskrit root “mā” (to measure or create), māyā originally signified magic or supernatural power. Over time, it evolved into a sophisticated metaphysical and epistemological concept, central to Vedantic philosophy. Primarily discussed in the Upanishads and developed extensively in the Vedanta schools, māyā explains the apparent multiplicity of the universe and the ignorance (avidyā) that obscures the true nature of reality. This post explores the origins, philosophical interpretations, and implications of māyā in the quest for liberation (mokṣa), where it denotes the magical or illusory power wielded by deities, particularly Indra and Varuṇa. In this context, māyā refers to the ability to create illusions or manipulate reality. However, it is in the Upanishads that māyā assumes a more philosophical dimension.

In the Upanishads, māyā is linked to ignorance (avidyā) and the misperception of reality. For example, the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad states that the world is a projection or appearance superimposed upon the unchanging reality, brahman. Similarly, the Māṇḍūkya Upanishad describes the world as a dream-like state, emphasizing the impermanence and illusory nature of phenomenal existence.

Māyā in Advaita Vedanta

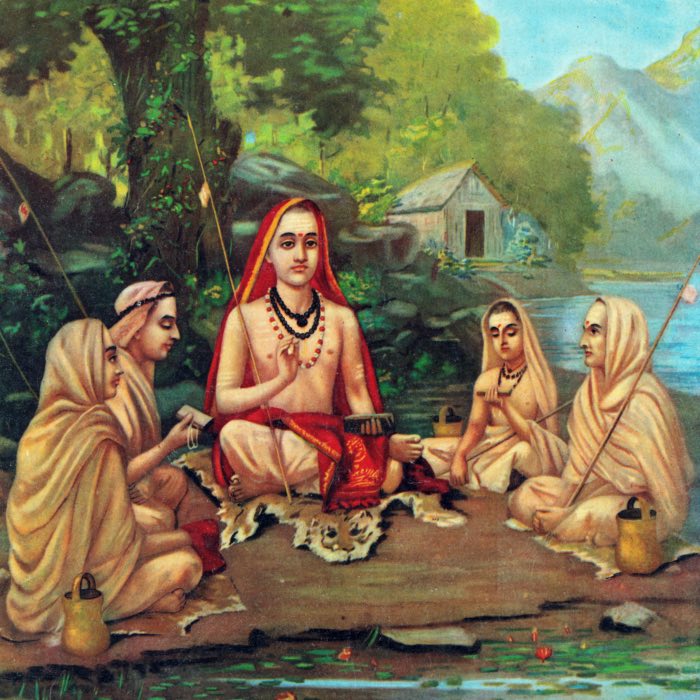

In Advaita Vedanta, Ādi Śaṅkara (8th century CE) elaborated on the concept of māyā, making it a cornerstone of his non-dualistic philosophy. According to Śaṅkara, māyā is the power of brahman that creates the illusion of the phenomenal world and veils the true nature of reality.

Key aspects of māyā in Advaita Vedanta include:

- Illusion and misperception: Māyā causes individuals to perceive the world as distinct from brahman, leading to the false identification of the self (ātman)) with the body and mind. This misperception is analogous to mistaking a rope for a snake in dim light—a classic example used by Śaṅkara.

- Superimposition (adhyāsa): The empirical world is superimposed upon brahman due to ignorance. Just as a mirage appears real until one realizes it is an illusion, the world appears real until one attains self-knowledge.

- Two levels of reality: Śaṅkara distinguishes between:

- Vyāvahārika satya: The empirical or transactional reality, which operates under the influence of māyā and appears real in daily life.

- Pāramārthika satya: The ultimate reality, where only brahman exists, and the world is recognized as illusory.

- Mokṣa as the dispelling of māyā: Liberation is achieved by realizing that ātman) and brahman are identical and that the world is merely an appearance created by māyā. This realization destroys ignorance and reveals the non-dual nature of reality.

Māyā in Viśiṣṭādvaita and Dvaita Vedanta

Unlike Advaita Vedanta, which emphasizes the illusory nature of the world, Viśiṣṭādvaita (qualified non-dualism) and Dvaita (dualism) Vedanta offer different interpretations of māyā.

In Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta, Rāmānuja rejected the idea that the world is an illusion. Instead, he viewed the world as a real manifestation of brahman’s attributes and power. In this context, māyā refers to the divine creative power of brahman (Viṣṇu), through which the world is brought into existence and sustained. Liberation involves recognizing one’s dependence on brahman and engaging in devotional practices (bhakti).

In contrast, Dvaita Vedanta, as proposed by Madhva, strongly opposed Śaṅkara’s interpretation of māyā as illusion. Madhva asserted that the world is real and eternally distinct from brahman. In Dvaita Vedanta, māyā represents the ignorance of the individual self regarding its dependence on brahman (Viṣṇu). Liberation is achieved through devotion and divine grace, not through the negation of the world’s reality.

Māyā in Sāṃkhya and Yoga

In Sāṃkhya and Yoga, māyā is conceptually similar to prakṛti (nature or matter), the primal material cause of the universe. These schools maintain a dualistic framework, distinguishing between:

- Puruṣa: Pure consciousness, analogous to ātman).

- Prakṛti: The material world, which appears real due to ignorance of the distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti.

Liberation, in this view, involves discerning the true nature of puruṣa and becoming free from the influence of prakṛti.

The epistemological implications of māyā

Māyā has significant epistemological implications in Hindu philosophy, particularly regarding the nature of knowledge (jñāna) and perception (pratyakṣa). Since māyā veils the true nature of reality, empirical knowledge derived from the senses is considered unreliable or incomplete. True knowledge, according to Vedanta, is direct realization of brahman, which transcends sensory perception and conceptual thought.

Śaṅkara and later Advaita philosophers emphasized viveka (discrimination) and ātma-vicāra (self-inquiry) as essential practices for overcoming māyā and attaining knowledge of the self.

Māyā in Hindu cosmology and theology

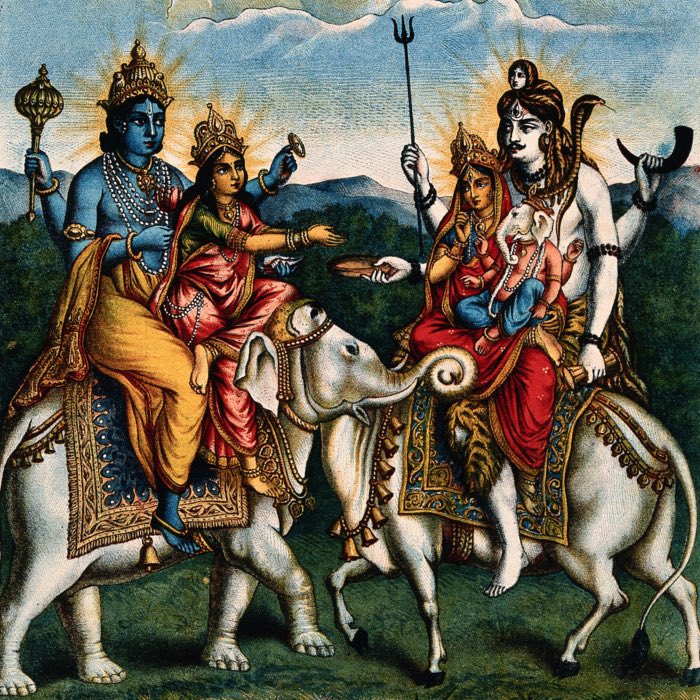

In Hindu cosmology, māyā is often associated with the creative power of the divine. In various theological traditions, it is depicted as the energy (śakti) through which the gods manifest and sustain the universe:

- In Śaivism: Māyā is considered one of the powers of Śiva, responsible for creating the world of forms and duality.

- In Śāktism: The Goddess (Devī), particularly in her forms as Durgā or Kālī, is identified with māyā as the creative and transformative force of the universe.

- In Vaishnavism: Māyā is the divine power of Viṣṇu, through which He creates and governs the world. In this context, māyā is real but subordinate to the supreme reality of Viṣṇu.

Conclusion

Māyā is a profound and complex concept in Hindu philosophy, offering insights into the nature of reality, perception, and liberation. While some schools view it as a veil of illusion obscuring the true nature of brahman, others interpret it as the creative power of the divine. Despite these differences, all schools agree that transcending māyā is essential for attaining spiritual liberation. Within the rich Hindu thought, māyā plays a central role in understanding the relationship between the individual self, the world, and the ultimate reality.

Maya, interpreted by DALL•E, “using a single continuous line to symbolize illusion and the layers of perception that obscure reality”.

References and further reading

- S. Radhakrishnan, The principal Upanishads, 1995, HarperCollins, ISBN: 978-8172231248

- Eliot Deutsch, Advaita Vedanta: A philosophical reconstruction, 1969, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824802714

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- R. Puligandla, Fundamentals of Indian philosophy, 1997, D.K. Printworld, ISBN: 978-8124600863

comments