The Korean Gojoseon Kingdom

The Gojoseon Kingdom represents the dawn of Korean civilization, traditionally believed to have been founded in 2333 BCE by the mythical figure Dangun. This early Korean state emerged in the northern regions of the Korean Peninsula and parts of Manchuria, serving as a foundation for subsequent Korean history. The development of Gojoseon reflects the interplay between indigenous traditions and influences from neighboring civilizations, particularly China. Its unique cultural identity and contributions to East Asian history underscore its importance.

Gojoseon and other dynasties of the time on the Korean peninsula, 108 BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Foundations and early development

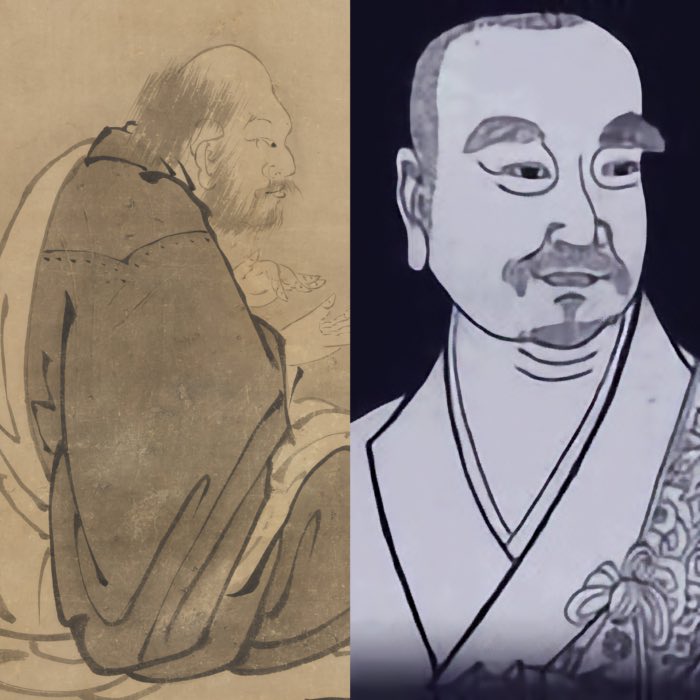

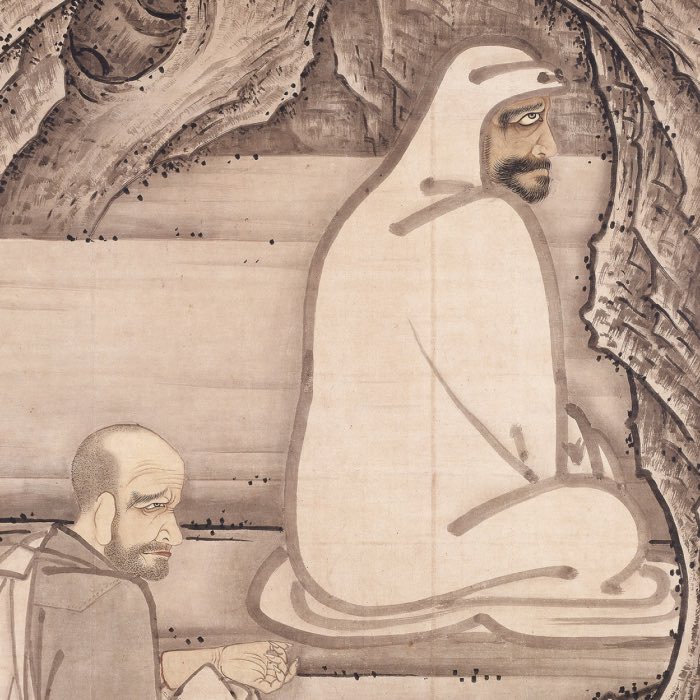

Gojoseon’s origin is deeply tied to the legend of Dangun, who is said to have descended from heaven to establish the kingdom. While the legend is largely mythical, archaeological evidence points to the existence of complex societies in the region during the Bronze Age (ca. 2000–1500 BCE). Sites such as Liaoning and Liaohe reveal early settlements with evidence of agriculture, bronze tools, and distinct cultural artifacts, suggesting a society capable of organized governance.

Portrait of Dangun (by Chae Yong-sin, 19–20th century). Dangun is thought to be the legendary founder of Gojoseon in 2333 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The development of Gojoseon was influenced by its geographical position. The region’s fertile river valleys, including the Daedong and Yalu rivers, supported agriculture and facilitated trade. These waterways also connected Gojoseon to the Yellow River basin, enabling cultural exchanges with early Chinese dynasties, such as the Shang and Zhou. The influence of Chinese metallurgy, writing systems, and governance models is evident in Gojoseon’s evolving society, yet the kingdom maintained a distinct identity.

Liaoning-style violin-shaped bronze knives. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Political and cultural characteristics

By the 8th century BCE, Gojoseon had developed into a centralized state characterized by organized governance and advanced social structures. Archaeological evidence points to the presence of walled cities, which not only provided defense but also symbolized the central authority of the governing elite. These fortified settlements were supported by a stratified society where artisans, farmers, and ruling classes played distinct roles in sustaining the kingdom.

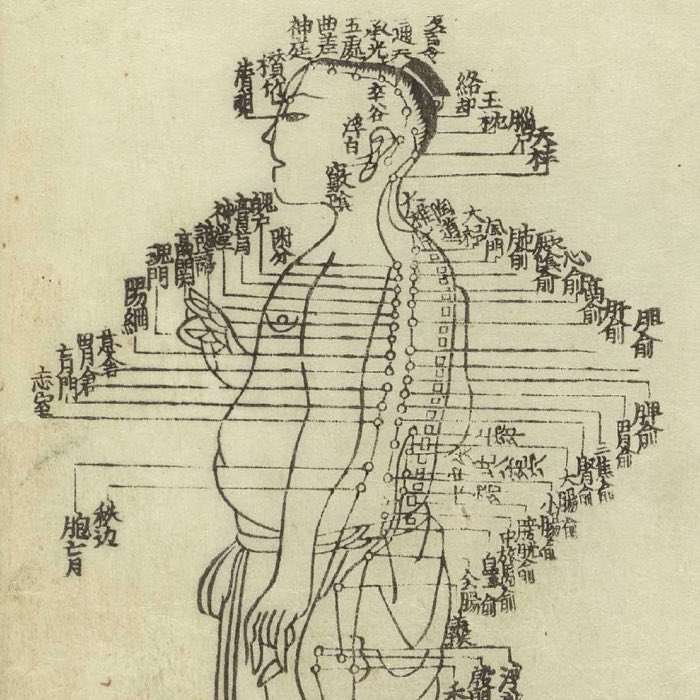

The advent of bronze technology marked a transformative period in Gojoseon’s development. This innovation revolutionized agriculture, enabling more efficient tools and practices that increased productivity. In warfare, bronze weaponry such as daggers and spears gave Gojoseon a strategic advantage, allowing it to defend its territories and assert influence over neighboring regions. Artistic expression also flourished during this era, as seen in the intricate designs of bronze mirrors, ceremonial vessels, and ritualistic items, which underscore the kingdom’s cultural sophistication.

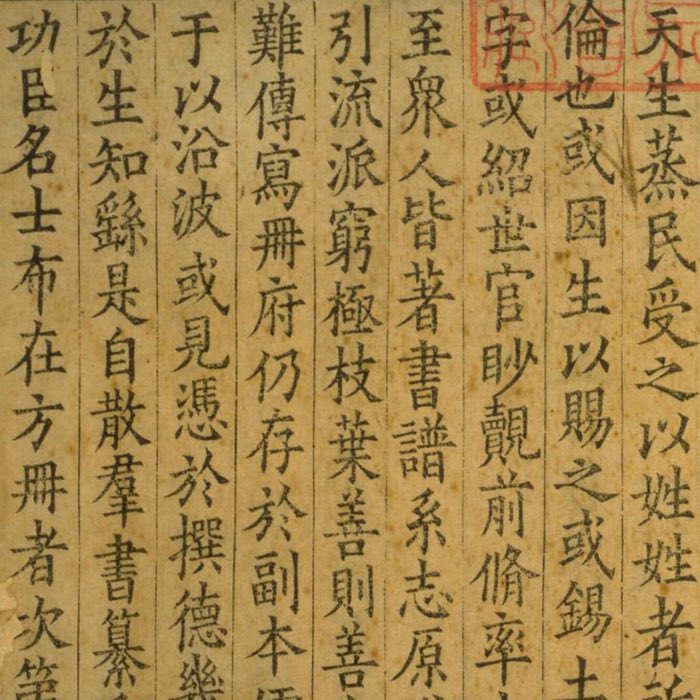

One of the most significant indicators of Gojoseon’s societal complexity was its legal system, encapsulated in the “Eight Prohibitions.” These laws, among the earliest codified legal frameworks in East Asia, emphasized the sanctity of human life and property. They prohibited theft, murder, and other transgressions, reflecting an organized and moral society that prioritized order and stability. The codification of laws also points to the existence of a literate and administratively capable ruling class, highlighting Gojoseon’s maturity as a centralized state.

Trade, culture and religious practices

Beyond governance, Gojoseon’s trade, culture, and religion played vital roles in its development. Archaeological evidence suggests that Gojoseon engaged in active trade with neighboring regions, including China and the Siberian steppe, exchanging goods such as bronze artifacts, agricultural products, and possibly textiles. These trade networks facilitated the diffusion of technology and cultural practices, enriching Gojoseon’s material and social complexity. The artistic achievements of the kingdom, including intricately designed bronze daggers and ceremonial vessels, reveal a culture deeply attuned to both functionality and aesthetics.

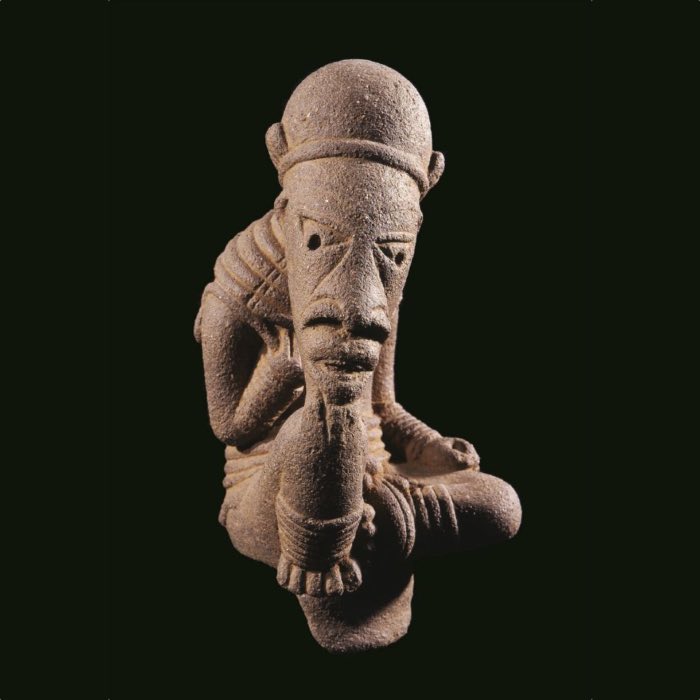

Large Middle Mumun (c. 8th century BE) storage vessel unearthed from a pit-house in or near Daepyeong. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Religious practices in Gojoseon are less well-documented but can be inferred from material evidence and later traditions. Ritual sites and artifacts suggest a spiritual system centered on nature worship and ancestor veneration, foundational elements that persisted in Korean culture. Some scholars hypothesize links between Gojoseon’s religious practices and proto-Shamanistic traditions, which emphasized harmony with the natural world and communication with spiritual forces. These practices, combined with the kingdom’s sophisticated legal and political structures, underscore the cultural depth and complexity of Gojoseon.

Relations with China and Japan

Gojoseon’s proximity to China profoundly shaped its development. The kingdom interacted with the Zhou Dynasty and later Chinese states, absorbing technological and administrative practices while maintaining its autonomy. During the Warring States period (ca. 475–221 BCE), increased contact with Chinese states brought iron technology and Confucian ideas to Gojoseon, influencing its governance and culture.

The establishment of the Han Dynasty in China led to increased conflict and cultural exchange. The Han’s campaigns against Gojoseon in the 2nd century BCE eventually resulted in the fall of Wiman Joseon (a later phase of Gojoseon) and the establishment of Chinese commanderies in the region. These commanderies served as conduits for Chinese culture, yet they also preserved and adapted local traditions.

In comparison, Gojoseon’s interactions with Japan were less direct but significant. The Yayoi culture in Japan (ca. 1000 BCE–300 CE) exhibited parallels with Korean advancements, such as rice agriculture and metallurgy, suggesting cultural transmission from the Korean Peninsula. Gojoseon likely played a role as a mediator of knowledge and technology between China and Japan.

Comparison with the developments in China and Japan

The development of Gojoseon mirrors and contrasts with the trajectories of China and Japan. Like China’s early dynasties, Gojoseon emerged as an agrarian society that transitioned into a centralized state. Both Gojoseon and early China utilized bronze technology to advance their societies, though Gojoseon adopted many aspects of Chinese metallurgy and governance while retaining its unique cultural elements. Unlike China, Gojoseon lacked an indigenous writing system during its early stages, relying instead on oral traditions and later adopting Chinese characters for record-keeping.

In contrast to Japan, which remained largely insular during the Yayoi period, Gojoseon was deeply interconnected with neighboring states. The Korean Peninsula served as a cultural bridge between China and Japan, transmitting technologies, religious ideas, and administrative practices. While Japan developed its early statehood later, Gojoseon’s influence on Yayoi culture is evident in shared advancements like bronze tools and wet-rice agriculture.

Decline and legacy

Gojoseon’s decline began with internal strife and increasing pressure from the Han Dynasty. In 108 BCE, Wiman Joseon fell to the Han, leading to the establishment of commanderies that integrated Chinese administration and culture into the region. Despite this political subjugation, the legacy of Gojoseon endured. The remnants of its culture influenced later Korean states, such as Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla, which carried forward Gojoseon’s traditions while forging their own identities.

Gojoseon’s historical significance lies in its role as the first Korean state and its contributions to the broader cultural and political developments of East Asia. Its interactions with China and Japan highlight its position as a key player in the region’s interconnected history. Furthermore, numerous small states and confederations arose from the remnants of Gojoseon, including Goguryeo, the Buyeo kingdom, Okjeo, and Dongye. These successor states continued Gojoseon’s legacy, shaping the course of Korean history and culture.

Further historical developments of Korean civilization

After the decline of Gojoseon, Korean history witnessed the rise of various kingdoms and dynasties that played pivotal roles in shaping the Korean Peninsula. Here is a brief overview of key historical periods and developments in Korean civilization:

Three Kingdoms period: Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla (57 BCE–68 CE)

The Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–68 CE) marked a critical era in Korean history, characterized by the rise of three powerful states: Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. These kingdoms emerged from the smaller polities that had developed following the fall of Gojoseon and the Han commanderies.

- Goguryeo (37 BCE–68 CE) was the largest of the three and occupied much of northern Korea and parts of Manchuria. Known for its military prowess, it frequently clashed with Chinese dynasties such as the Han, Wei, and Sui.

- Baekje (18 BCE–660 CE) developed in the southwestern part of the Korean Peninsula. It became a significant cultural bridge between Korea and Japan, facilitating the spread of Buddhism and advanced technologies.

- Silla (57 BCE–935 CE) began as a small kingdom in the southeast but eventually unified much of Korea. Initially the weakest of the three, it formed strategic alliances with Tang China to overcome its rivals.

Map of the Three Kingdoms of Korea — Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla — in the 5th century CE, at the height of Goguryeo’s territorial expansion. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

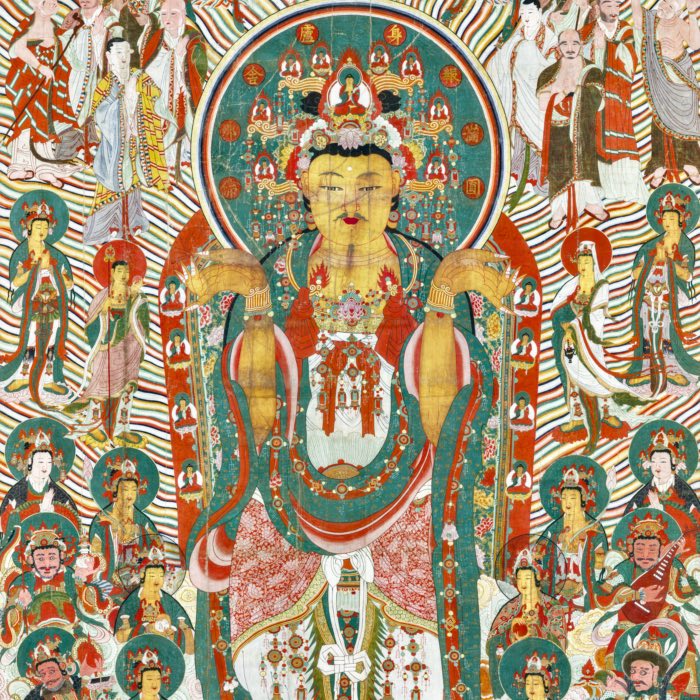

Introduction of Buddhism (4th century CE)

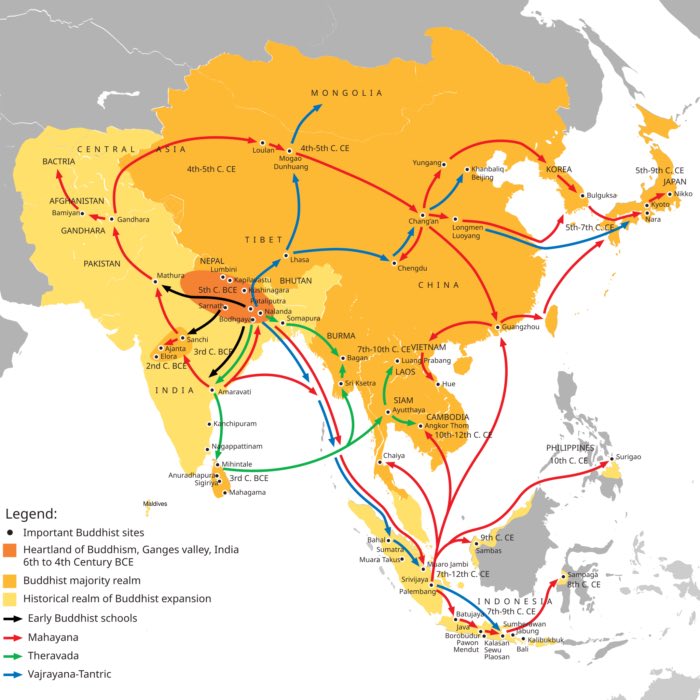

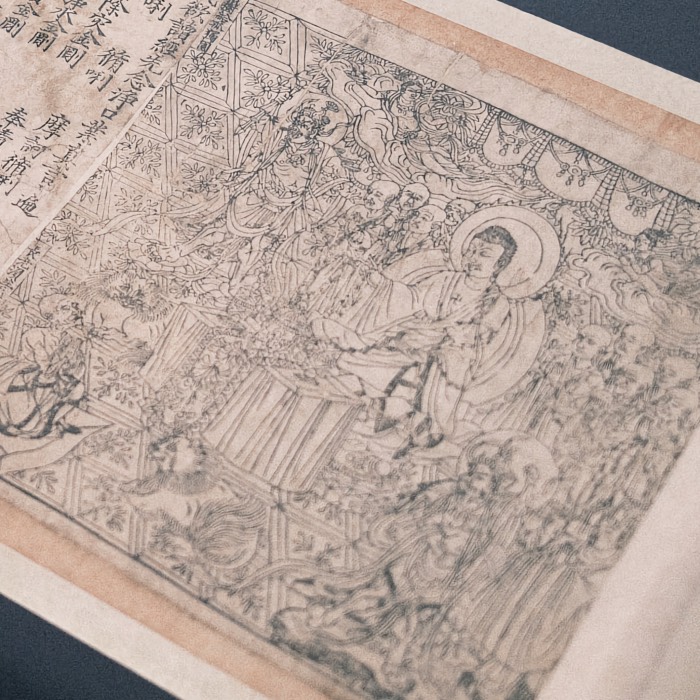

Buddhism was introduced to Korea from China during the early 4th century CE and quickly became a significant cultural and religious force. The adoption of Buddhism by the ruling elites of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla contributed to the development of art, architecture, and philosophy.

- Goguryeo embraced Buddhism in 372 CE, under King Sosurim.

- Baekje adopted Buddhism in 384 CE during the reign of King Chimnyu.

- Silla was the last to officially accept Buddhism, doing so in the 5th century.

Buddhism played a crucial role in unifying the people and legitimizing the authority of the ruling class. Temples, sculptures, and pagodas from this period reflect the influence of Chinese and Indian styles, adapted to Korean aesthetics.

Unified Silla period (668–935 CE)

Silla, with the help of Tang China, successfully unified the Korean Peninsula in 668 CE after defeating Goguryeo and Baekje. This unification ushered in a period of relative peace and cultural flourishing known as the Unified Silla period.

During this time, Silla established strong central governance and promoted Buddhism as the state religion. Notable cultural achievements include the construction of Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Grotto, both of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Additionally, the Silla royal court maintained close diplomatic and cultural ties with Tang China, facilitating the exchange of ideas and technologies.

Balhae in the north, Unified Silla in the south, 830s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Balhae kingdom (698–926 CE)

After the fall of Goguryeo, the Balhae kingdom was established by Dae Joyeong in the northern regions of Korea and parts of Manchuria. Balhae is often considered a successor state to Goguryeo and maintained a distinct identity despite the dominance of Unified Silla in the south.

Balhae’s culture combined elements of Goguryeo and Chinese traditions, resulting in a rich artistic and architectural heritage. Its decline in 926 CE, following invasions by the Khitans, marked the end of this northern kingdom.

Goryeo dynasty (918–1392 CE)

The Goryeo dynasty (918–1392 CE), established by King Taejo in 918 CE, succeeded Unified Silla and unified the Korean Peninsula by 936 CE. The name “Korea” is derived from “Goryeo”.

Map of Goryeo in 1389. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

During this period, Buddhism reached its zenith, and significant cultural achievements were made. The Goryeo dynasty is particularly renowned for:

- The creation of the Tripitaka Koreana, a comprehensive collection of Buddhist scriptures carved onto over 80,000 wooden printing blocks.

- Celadon pottery, which became highly prized for its intricate designs and unique glaze.

- The establishment of a civil service examination system, inspired by the Chinese model, to recruit talented officials based on merit rather than lineage.

However, the Goryeo dynasty faced numerous challenges, including invasions by the Khitans, Jurchens, and Mongols. Despite these pressures, it managed to maintain its sovereignty until the late 14th century.

Joseon dynasty (1392–1910)

The Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), founded by Yi Seong-gye in 1392, marked a significant shift in Korean history. While Buddhism had dominated the previous eras, Joseon adopted Neo-Confucianism as its state ideology, leading to profound changes in governance, society, and culture.

Key developments during the Joseon dynasty include:

- The establishment of a rigid social hierarchy, with a focus on Confucian values such as filial piety and loyalty.

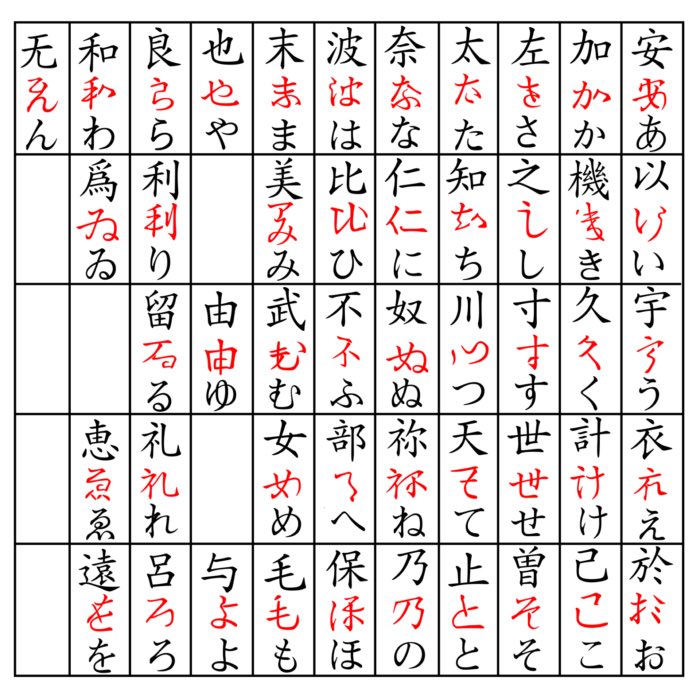

- The creation of Hangul, the Korean alphabet, by King Sejong in 1443. Hangul is considered one of the most significant cultural achievements in Korean history, as it enabled widespread literacy among the population.

- Advancements in science and technology, including the invention of the rain gauge, water clocks, and astronomical instruments.

The Joseon dynasty also fostered a rich cultural heritage, producing notable works in literature, art, and philosophy. However, it faced internal strife and external threats, particularly from Japan and China.

Japanese invasions and Manchu invasions (16th–17th centuries)

In the late 16th century, Korea faced a significant crisis with the Japanese invasions (1592–1598) led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Although the invasions caused widespread destruction, Korea successfully repelled the Japanese forces with the help of Ming China. Admiral Yi Sun-sin’s innovative use of the “turtle ship” played a crucial role in defending Korea’s coastline.

In the early 17th century, Korea faced additional challenges from the Manchu invasions (1627 and 1636). These invasions resulted in Korea becoming a tributary state of the Qing dynasty, although it maintained significant autonomy.

Late Joseon period (18th–19th centuries)

The late Joseon period (18th–19th centuries) was marked by internal decline, social unrest, and increasing foreign pressure. Attempts at reform, such as the Silhak (Practical Learning) movement, sought to modernize Korea and address its social and economic issues. However, resistance from conservative factions hindered significant progress.

Korean Empire and Japanese colonization (1897–1945)

In 1897, King Gojong declared Korea an empire, seeking to assert greater independence in the face of growing Japanese and Russian influence. Despite these efforts, Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910 following years of political maneuvering and military pressure.

During the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945), Korea experienced significant hardship, including the suppression of its culture and exploitation of its resources. However, the period also saw the rise of a nationalist movement that would later play a crucial role in Korea’s independence.

Division and Korean War (1945–1953)

Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, Korea was divided along the 38th parallel, with the Soviet Union occupying the north and the United States occupying the south. This division led to the establishment of two separate governments in 1948: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea).

Left: North (orange) and South Korea (blue) as of today. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: The division in 2024 is clearly visible from space with a higher amount of light emitted into space from the South than the North. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Korean War (1950–1953) erupted when North Korea, supported by China and the Soviet Union, invaded South Korea. The war resulted in significant devastation and ended in an armistice, with the Korean Peninsula remaining divided.

Postwar Korea (1953–present)

In the decades following the Korean War, South Korea underwent rapid industrialization and economic growth, becoming one of the world’s leading economies. Key developments include:

- The Miracle on the Han River, a period of rapid economic growth during the 1960s to 1990s.

- Democratization, culminating in the establishment of a democratic government in the late 20th century.

North Korea, by contrast, remained isolated under a totalitarian regime, facing economic challenges and international sanctions.

Timeline summary

- ca. 2333 BCE – Traditional founding of Gojoseon by Dangun

- 108 BCE – Fall of Wiman Joseon to Han China, establishment of Chinese commanderies

- 57 BCE–68 CE – Three Kingdoms period: Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla

- 372–400 CE – Introduction of Buddhism to the Three Kingdoms

- 668–935 CE – Unified Silla period, cultural flourishing

- 698–926 CE – Balhae kingdom in the north

- 918–1392 CE – Goryeo dynasty, unification and cultural achievements

- 1392–1910 CE – Joseon dynasty, Confucian state and cultural development

- 1592–1598 CE – Japanese invasions

- 1627–1636 CE – Manchu invasions

- 1897–1910 CE – Korean Empire

- 1910–1945 CE – Japanese colonization

- 1945–1948 CE – Division of Korea

- 1950–1953 CE – Korean War

- 1953–present – Postwar recovery and modernization

Conclusion

The history of Korean civilization is a story of resilience, adaptation, and cultural synthesis. From the legendary founding of Gojoseon to the division of the peninsula in the 20th century, Korea has experienced periods of unification, foreign invasions, and remarkable cultural achievements. The introduction of Buddhism, the rise of the Joseon dynasty with its Confucian ideals, and the creation of the Korean alphabet, Hangul, are among the defining milestones of Korean history.

Despite periods of foreign domination and internal conflict, Korea’s cultural heritage and identity have endured. The postwar economic recovery and modernization of South Korea refelcts the country’s resilience and determination. Meanwhile, the continuing division of the peninsula serves as a reminder of the complex legacy of the Korean War.

Understanding Korea’s historical trajectory provides valuable insights into its cultural identity, regional influence, and the challenges it faces in the modern era. As Korea continues to navigate its future, its rich history remains a foundation upon which it builds its national character and aspirations.

References

- Ki-baik Lee, A New History of Korea, 2023, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300259810

- Mark E. Byington, The Ancient State of Puyō in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory, 2016, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674737198

- Sarah Milledge Nelson, The Archaeology of Korea, 1993, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521407830

- Gina Lee Barnes, Archaeology Of East Asia - The Rise Of Civilization In China, Korea And Japan, 2015, Oxbow Books Limited, ISBN: 9781785700705

- Gina L. Barnes, State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, 2000, Taylor & Francis Ltd, ISBN: 978-0700713233

- Hyung Il Pai, Constructing “Korean” Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology, Historiography, and Racial Myth in Korean State-Formation Theories, 2000, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674002449

- Jun-Hyeok Kwak and Melissa Lane (Eds.), Comparative Political Theory and Cross-Cultural Philosophy in East Asia, 2009, Lexington Books, ISBN: 978-0739122679

- Michael J. Seth, A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present, 2019, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN: 978-1538128985

- J. Mark Kenoyer, Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195779400

- Jonathan W. Best, A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, 2007, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674019577

- Andrew C. Nahm, Korea: Tradition and Transformation, 1996, Korean Book Services, ISBN: 978-0930878566

- Wikipedia article on Gojoseonꜛ

comments