Karma and Samsāra: The cycle of action and rebirth in Hindu philosophy

Karma and Samsāra are fundamental concepts in Hindu philosophy, intricately linked to the notion of liberation (mokṣa). The law of karma governs moral causality, implying that actions have consequences not only in this life but also in future lives. Samsāra refers to the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth driven by karma and ignorance (avidyā). Together, these concepts form the basis for Hindu ethics, metaphysics, and soteriology. The ultimate goal in Hinduism is to break free from samsāra through knowledge, devotion, or selfless action, thereby attaining liberation. In this post, we explore the origins, philosophical interpretations, and practical implications of karma and samsāra in Hindu thought.

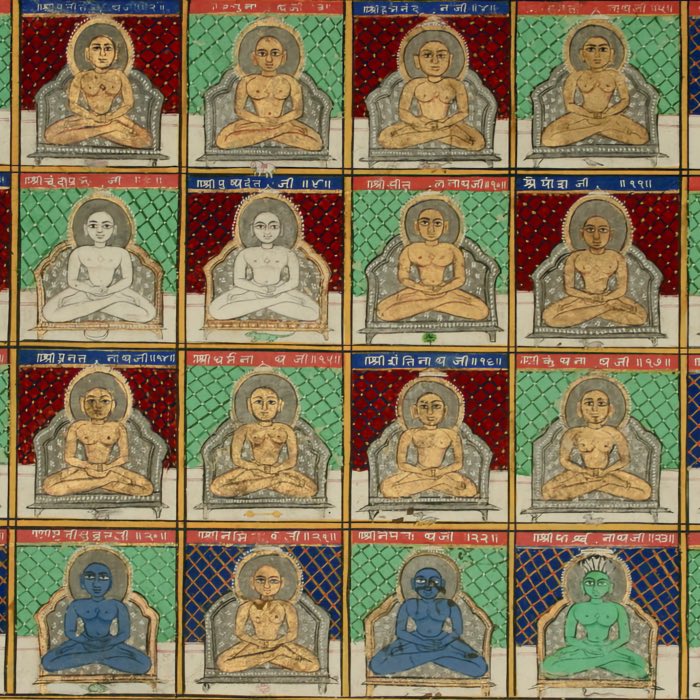

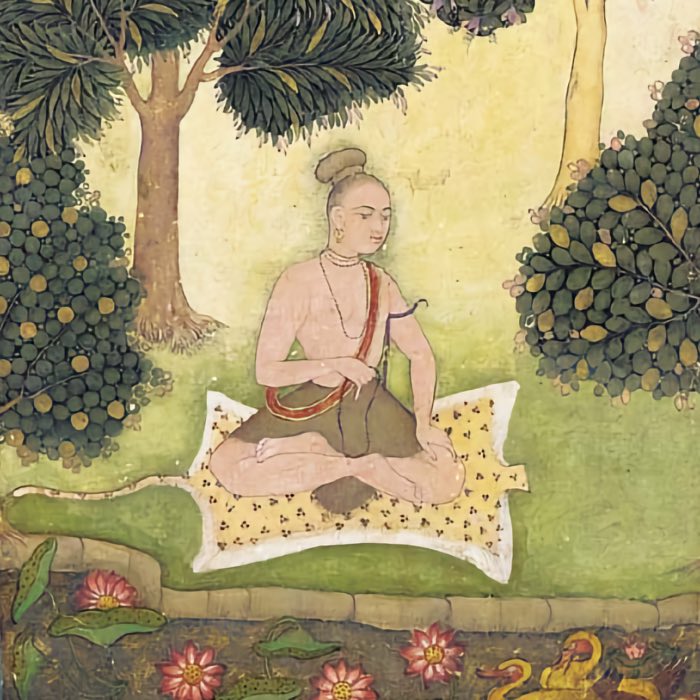

A painting of the bhavachakra that depicts an emanation of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in each realm. A bhavachakra is a symbolic representation of the cycle of birth and rebirth in samsāra. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The origins of karma and samsāra

The earliest references to karma appear in the Vedas, where the term originally referred to ritual action or sacrificial rites. Performing these actions correctly was believed to sustain cosmic order (ṛta) and ensure prosperity. Over time, however, the concept of karma expanded beyond ritual to encompass all human actions and their ethical consequences.

The idea of samsāra as the cycle of rebirth emerged in the Upanishadic period (circa 800–300 BCE). The Upanishads present a shift in focus from external ritualism to internal contemplation and the pursuit of liberation. According to these texts, the individual self (ātman)) is bound to the cycle of samsāra due to ignorance of its true nature and the accumulation of karma.

Key passages from the Upanishads illustrate this evolving understanding:

- Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad: “As a person acts, so he becomes. A person of good deeds becomes good, a person of evil deeds becomes evil.”

- Chāndogya Upanishad: Describes samsāra as a journey of the self through various births, driven by desire and ignorance.

Karma: The law of cause and effect

In Hindu[Hindu](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-01-02-hinduism/), karma refers to the principle of moral causality, where every action generates consequences that affect the doer. This law operates automatically, without the intervention of any deity, ensuring that moral order is maintained across lifetimes.

Types of karma

Hindu philosophers classify karma into three types:

- Sañcita karma: Accumulated actions from past lives whose consequences have not yet been experienced.

- Prārabdha karma: The portion of accumulated karma that has begun to bear fruit in the present life. It is responsible for one’s current circumstances, such as birth, social status, and lifespan.

- Āgāmi karma: Actions performed in the present life that will bear fruit in future lives.

Liberation (mokṣa) is achieved by exhausting one’s prārabdha karma while preventing the generation of new āgāmi karma, thus breaking the cycle of rebirth.

Ethical implications of karma

Karma serves as the basis for Hindu ethics, emphasizing personal responsibility and the moral consequences of one’s actions. It encourages individuals to act righteously (dharma) and cultivate virtues such as truthfulness, non-violence (ahiṃsā), and compassion. Since karma operates across lifetimes, it also promotes the idea of cosmic justice, where every individual eventually reaps the fruits of their actions.

Samsāra: The cycle of rebirth

Samsāra refers to the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth driven by karma and desire. The self (ātman)) takes on various forms across lifetimes, experiencing the fruits of its actions in different existences. This cycle is governed by the following principles:

- Rebirth (punarjanma): The self is reborn in different forms, such as human, animal, or even divine, depending on its karma. The nature of one’s birth is determined by the moral quality of one’s actions in previous lives. While a metaphysical concept, the idea of a continuous stream of consciousness without a fixed self finds interesting parallels in modern neuroscience.

- Desire and attachment: Samsāra is perpetuated by desire (kāma) and attachment (rāga). As long as individuals remain attached to the fruits of their actions, they remain bound to the cycle of rebirth.

- Suffering (dukkha): Existence within samsāra is inherently marked by suffering, due to the impermanence of all worldly things. Liberation involves transcending this cycle and attaining a state of eternal bliss.

Paths to liberation (mokṣa)

Hindu philosophy offers several paths to break free from samsāra and attain mokṣa:

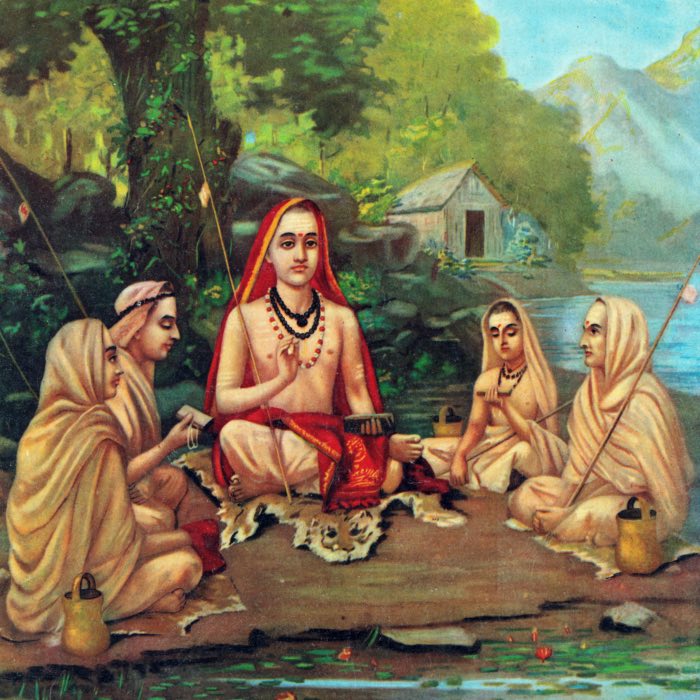

- Jñāna yoga (path of knowledge)

- Central to Advaita Vedanta, this path involves self-inquiry (ātma-vicāra) and the realization of one’s identity with brahman. Knowledge of the self as non-different from the ultimate reality dispels ignorance and ends the cycle of rebirth.

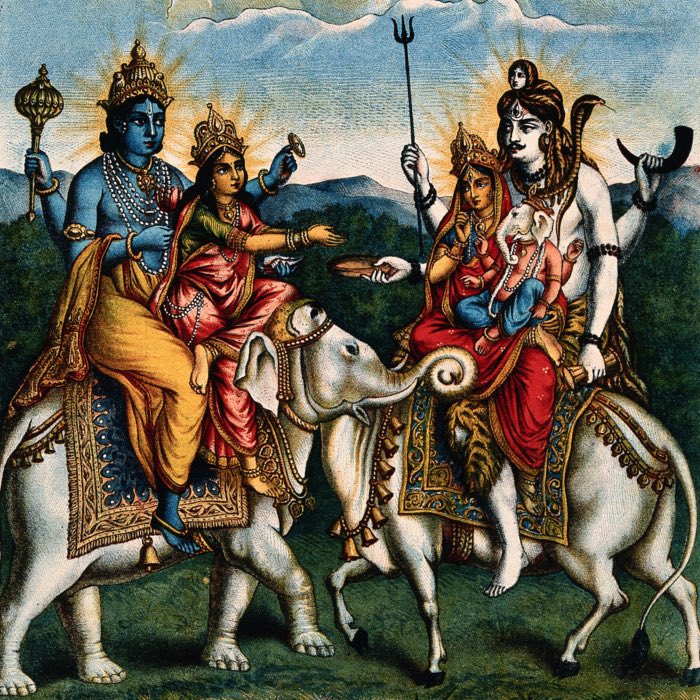

- Bhakti yoga (path of devotion)

- Popular in devotional traditions, this path emphasizes surrender and devotion to a personal deity, such as Viṣṇu or Śiva. Through divine grace, devotees can transcend karma and attain liberation.

- Karma yoga (path of selfless action)

- Taught in the Bhagavad Gītā, karma yoga involves performing one’s duties without attachment to the results. By renouncing the fruits of action, individuals prevent the accumulation of new karma and move toward liberation.

- Rāja yoga (path of meditation)

- Described in Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras, this path focuses on disciplined meditation and control of the mind to achieve self-realization and freedom from samsāra.

Philosophical interpretations of karma and samsāra

Different schools of Hindu philosophy offer nuanced interpretations of karma and samsāra:

- Advaita Vedanta

- In Advaita, karma and samsāra are seen as products of ignorance (avidyā). Liberation involves realizing the non-duality (advaita) of ātman) and brahman, thereby transcending both karma and samsāra.

- Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta

- Rāmānuja’s school acknowledges the reality of karma and samsāra, but emphasizes devotion (bhakti) to Viṣṇu as the means of liberation. The individual self retains its identity even after liberation but remains eternally united with brahman.

- Dvaita Vedanta

- Madhva’s dualistic philosophy views karma and samsāra as real and eternal processes. Liberation is achieved through unwavering devotion to Viṣṇu and reliance on His grace.

- Sāṃkhya and Yoga

- These schools maintain a dualistic view, distinguishing between puruṣa (pure consciousness) and prakṛti (matter). Samsāra results from the self’s misidentification with prakṛti. Liberation involves discriminating between the two and realizing one’s nature as puruṣa.

Conclusion

Karma and samsāra are central to Hindu philosophy, shaping its understanding of life, ethics, and liberation. The law of karma ensures moral order and continuity across lifetimes, while samsāra represents the cyclical nature of existence. Hindu traditions offer various paths to transcend this cycle, emphasizing knowledge, devotion, and selfless action as means to attain liberation. By understanding these profound concepts, one gains insight into the Hindu worldview and its approach to the achieve the Hindu ultimate goal, mokṣa (liberation).

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- Eliot Deutsch, Advaita Vedanta: A philosophical reconstruction, 1969, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824802714

- Eknath Easwaran (translator), Bhagavad Gītā, 2012, Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 978-3442220137

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

comments