The Jomon culture in Japan

The Jomon culture represents one of the earliest examples of prehistoric human societies in Japan, dating back as far as 14,000 BCE and lasting until approximately 300 BCE. Named after the distinctive cord-marked pottery (jomon in Japanese) characteristic of the period, this culture is notable for its long continuity, intricate craftsmanship, and adaptation to diverse environments. The Jomon period laid the foundations for later developments in Japanese civilization while maintaining unique traditions that set it apart from neighboring cultures in China and Korea.

The Japanese archipelago, during the last glaciation in about 20,000 BCE. Orange: regions above sea level, White: unvegetated, Blue: sea. During the last glacial maximum, the sea level was about 120 m lower than today, which caused the establishment of the land bridge between the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese archipelago. This, in turn, allowed the migration of humans and animals to Japan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Origins and early development

The Jomon culture emerged during the transition from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic period in Japan. Early Jomon communities were primarily hunter-gatherers who also engaged in small-scale horticulture. The abundance of natural resources in Japan’s forests, rivers, and coastal areas provided a stable subsistence base, allowing these communities to establish semi-permanent settlements. Archaeological sites, such as Sannai-Maruyama in northern Honshu, reveal large, organized villages with pit dwellings, storage facilities, and evidence of communal activity.

Reconstruction of the Sannai-Maruyama Site in the Aomori Prefecture, Japan. It shares cultural similarities with settlements of Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula, as well as with later Japanese culture. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The pottery of the Jomon period is among the oldest in the world, with early examples dating back to around 14,000 BCE. These artifacts were initially utilitarian but became increasingly elaborate over time, featuring intricate designs and ceremonial purposes. This artistic evolution reflects the growing complexity of Jomon society.

Incipient Jōmon pottery, 14th–8th millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Cultural achievements and social organization

Jomon society was characterized by a sophisticated material culture, including pottery, stone tools, and lacquered objects. Their pottery, often decorated with cord patterns and abstract motifs, served both practical and symbolic functions. Some vessels were used for cooking and storage, while others held ritualistic significance, as evidenced by their placement in graves and ceremonial sites.

Jōmon pottery in the Yamanashi museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Social organization in Jomon communities appears to have been relatively egalitarian, with limited evidence of hierarchical structures. However, certain grave goods and the construction of monumental structures, such as stone circles, suggest the presence of spiritual leaders or communal rituals that reinforced social cohesion. The construction of storage pits and the accumulation of surplus food indicate the beginnings of social stratification and resource management.

Reconstruction of Jōmon period houses in the Aomori Prefecture, Japan. . Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Jomon people also demonstrated an affinity for symbolic art and spirituality. Dogu figurines, small clay sculptures often depicting anthropomorphic or zoomorphic forms, are believed to have been used in fertility or healing rituals. These artifacts provide insights into the spiritual beliefs and cosmology of the Jomon people, highlighting their connection to nature and the supernatural.

Left: Spray style Jōmon pottery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Clay statue, late Jōmon period (1000–400 BCE), Tokyo National Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: Late Jōmon clay statue, Kazahari I, Aomori Prefecture, 1500–1000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Late Jōmon clay head, Shidanai, Iwate Prefecture, 1500–1000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Interactions with neighboring cultures

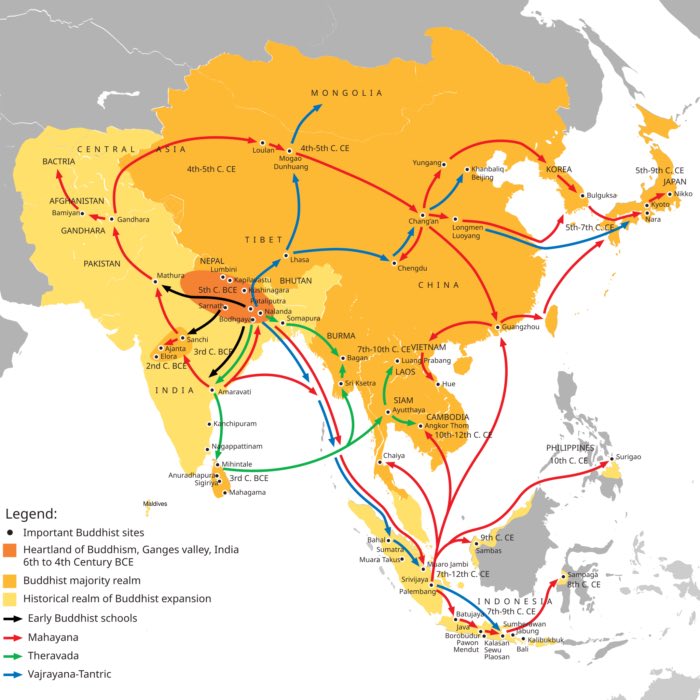

While the Jomon culture developed in relative isolation due to Japan’s insular geography, it interacted indirectly with neighboring regions, particularly Korea and China. During the later Jomon period, there is evidence of contact with the Korean Peninsula, likely through trade or migration. These interactions introduced new technologies, such as rice cultivation and metallurgy, which would become more prominent during the subsequent Yayoi period.

In contrast to the agricultural societies of early China, such as those associated with the Yangshao and Longshan cultures, the Jomon culture retained its hunter-gatherer economy for millennia. This divergence reflects the abundance of natural resources in Japan and the adaptability of Jomon communities to their environment. However, the influence of Chinese agricultural and ceramic technologies is evident in later Japanese developments, bridging the gap between the Jomon and Yayoi periods.

The Korean Peninsula served as a cultural intermediary between China and Japan, transmitting technological and cultural innovations. While the Yayoi culture is more closely associated with these exchanges, the Jomon period likely saw early instances of such interactions, contributing to Japan’s gradual integration into the broader East Asian cultural sphere.

Comparison with developments in China and Korea

The Jomon culture contrasts sharply with the agricultural and urbanized societies of China and Korea during the same period. In China, the Yangshao and Longshan cultures (ca. 5000–1900 BCE) exhibited advanced agricultural techniques, centralized settlements, and early state formation, features absent in Jomon society. The Korean Peninsula, during the Chulmun period (ca. 8000–1500 BCE), displayed some similarities to the Jomon in terms of pottery and subsistence strategies but transitioned earlier to agriculture and more hierarchical social structures.

Despite these differences, the Jomon culture shares thematic parallels with its neighbors. All three regions placed significant importance on pottery, ritual practices, and community cohesion. However, the Jomon culture’s longevity and its focus on harmony with nature distinguish it as a unique case of cultural development.

Decline and transition

The decline of the Jomon culture began around 1000 BCE, coinciding with the introduction of rice agriculture and bronze tools from the Korean Peninsula. These innovations marked the beginning of the Yayoi period, which gradually replaced the Jomon way of life. The transition from hunting and gathering to a predominantly agricultural society brought significant social and economic changes, including the emergence of social stratification and centralized governance.

Although the Jomon culture faded, its legacy persisted in Japanese art, spirituality, and reverence for nature. The symbolic motifs and craftsmanship of Jomon pottery influenced later Japanese aesthetics, while the deep connection to the environment remains a cornerstone of Japanese cultural identity.

Further historical developments of the Japanese civilization

Following the Jomon period, Japan underwent a series of transformative eras that shaped its cultural, political, and social landscape. In the following, we provide a brief overview of key historical periods in Japanese history.

Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE)

The Yayoi period (ca. 300 BCE–300 CE) marked a significant transformation in Japanese society with the introduction of rice agriculture, iron, and bronze technology. Originating from the Korean Peninsula and China, these innovations led to the gradual replacement of the Jomon hunter-gatherer lifestyle by a more agrarian society. Archaeological evidence from Yayoi sites reveals permanent settlements, irrigation systems, and the emergence of social stratification.

Rice cultivation, in particular, became a staple of Japanese agriculture, enabling population growth and the development of complex communities. The Yayoi period also saw the introduction of new tools and weapons made of iron and bronze, which further facilitated societal organization and defense.

Kofun period (ca. 300–750)

The Kofun period (ca. 300–750 CE), named after the distinctive burial mounds (kofun) built for the elite, marked the emergence of centralized political authority. These mounds, often accompanied by clay figurines known as haniwa, reflect the growing power of regional rulers and the formation of early state structures.

Territorial extent of Yamato court during the Kofun period. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

During this period, Japan began to establish connections with China and Korea, as evidenced by the adoption of Chinese writing and Confucian concepts. The Yamato clan, which would later evolve into the imperial family, emerged as a dominant political force, laying the foundation for the Japanese monarchy.

Asuka and Nara periods (538–794)

The Asuka period (538–710 CE) saw the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, a significant cultural and religious development. Buddhism, introduced from Korea and China, gained the support of powerful clans such as the Soga and played a central role in shaping Japanese art, architecture, and governance.

The Nara period (710–794 CE) marked the establishment of Japan’s first permanent capital at Nara. Modeled after the Chinese capital Chang’an, Nara became a center of political and cultural activity. The compilation of historical records such as the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki during this era highlights the consolidation of imperial authority and the influence of Chinese culture on Japanese governance.

Heian period (794–1185)

The Heian period (794–1185 CE) is renowned for its cultural achievements and the development of a distinct Japanese identity. The imperial court in Kyoto became a hub of literary and artistic activity, producing masterpieces such as The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu.

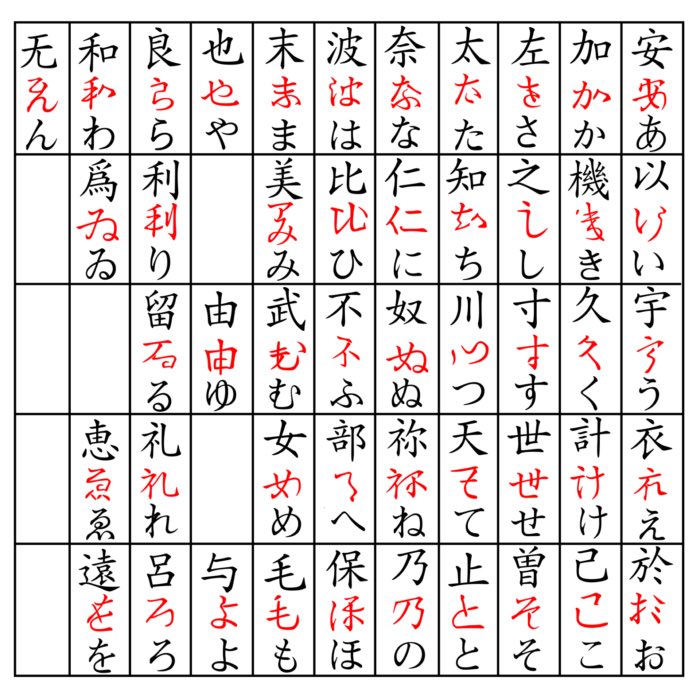

While the court aristocracy enjoyed a refined lifestyle, political power gradually shifted to regional warrior clans, setting the stage for the rise of the samurai. The period also saw the development of kana scripts, enabling the creation of a uniquely Japanese literary tradition.

Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1185–1573)

The Kamakura period (1185–1333) marked the establishment of the first shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo, ushering in an era of military rule. The samurai class rose to prominence, and Zen Buddhism, introduced from China, became influential among the warrior elite.

The Muromachi period (1336–1573), under the Ashikaga shogunate, saw continued military dominance and cultural flourishing. Notable developments include the construction of iconic temples such as Kinkaku-ji and the rise of Noh theater. However, political fragmentation and conflict among regional warlords, or daimyo, characterized the latter part of this era.

Map showing the territories of major daimyō families around 1570. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1600)

The Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1600) was a time of political unification under powerful warlords such as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Their military campaigns and political reforms laid the groundwork for a centralized state.

This period also saw increased contact with European traders and missionaries, introducing new technologies, goods, and Christianity to Japan. The influence of Portuguese and Spanish traders is evident in the adoption of firearms and Western-style fortifications.

Edo period (1600–1868)

The Edo period (1600–1868), also known as the Tokugawa period, was characterized by political stability under the Tokugawa shogunate. The policy of sakoku (national isolation) limited foreign influence while promoting internal economic growth and cultural development.

Despite isolation, trade continued with China, Korea, and the Dutch at Nagasaki. The period saw the flourishing of urban culture, with developments in literature, art (ukiyo-e), and entertainment, including kabuki theater. The samurai class maintained social order, while the merchant class grew in wealth and influence.

Meiji period (1868–1912)

The Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) marked the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the beginning of rapid modernization and industrialization. Japan adopted Western technologies, institutions, and military practices, transforming itself into a modern nation-state.

During this period, Japan established a constitutional monarchy, built a modern industrial economy, and expanded its influence through military victories in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).

Taisho and Showa periods (1912–1945)

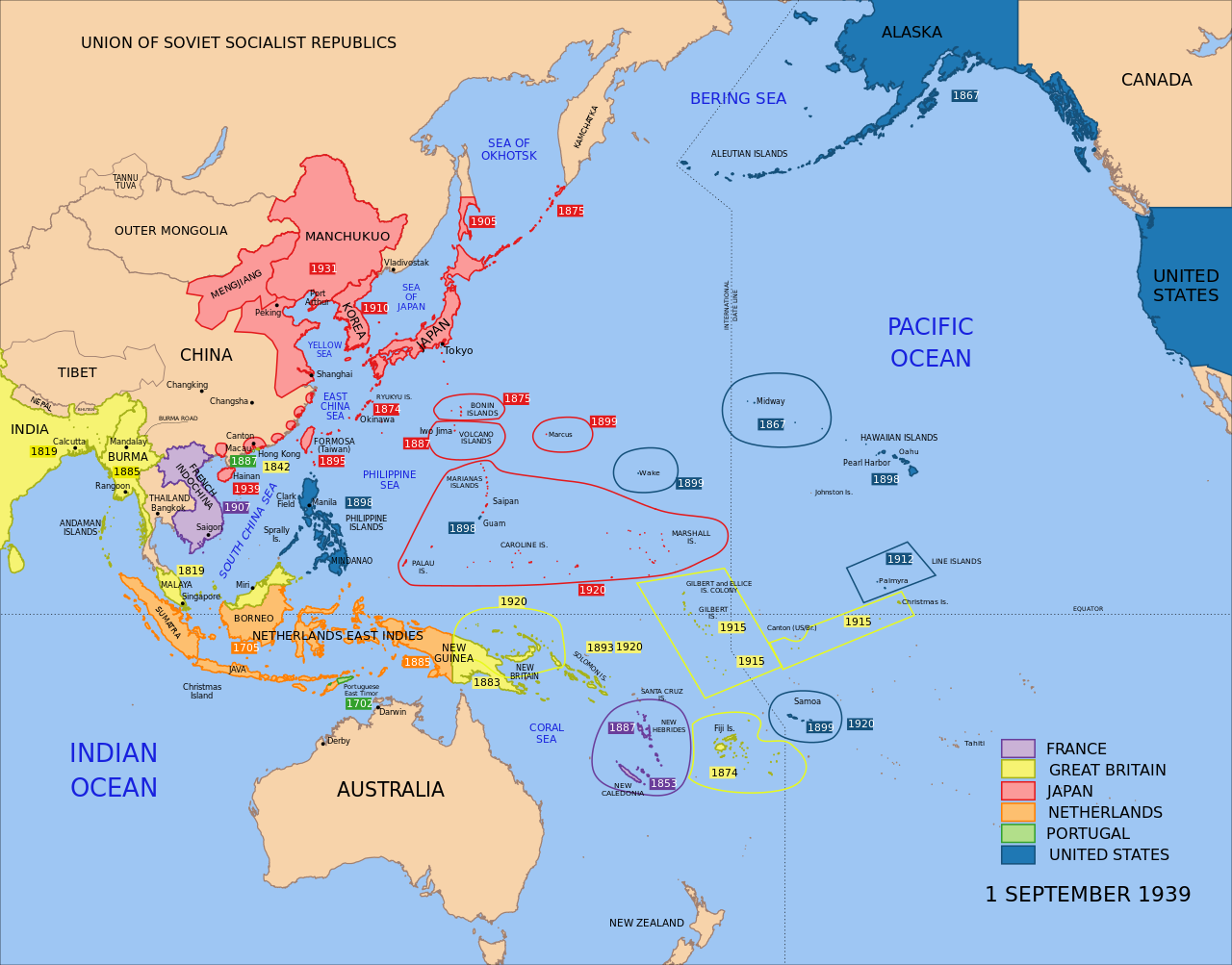

The Taisho period (1912–1926) saw the continued modernization of Japan and the emergence of democratic institutions. However, during the early Showa period (1926–1945), ultranationalism, militarism and imperial expansion dominated Japanese policy. Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and its participation in World War II as part of the Axis Powers led to significant territorial gains and eventual defeat in 1945.

The Japanese Empire in 1939. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Japan’s subsequent surrender marked the end of World War II and the beginning of Allied occupation.

Postwar Japan (1945–1989)

Under the guidance of the United States, Japan adopted a new constitution in 1947, emphasizing pacifism and democratic governance. The postwar period saw rapid economic recovery, leading to the “Japanese economic miracle” of the 1950s to 1980s, during which Japan became one of the world’s leading industrial powers.

Heisei and Reiwa periods (1989–present)

The Heisei period (1989–2019) was marked by economic stagnation following the burst of the asset price bubble. Despite economic challenges, Japan remained a global leader in technology and innovation. Social issues such as an aging population and low birth rates became prominent during this time.

The Reiwa period, beginning in 2019, continues to grapple with these challenges while emphasizing cultural heritage and technological advancement.

Timeline summary

- ca. 14,000 BCE–300 BCE – Jomon period, hunter-gatherer culture with cord-marked pottery

- ca. 300 BCE–300 CE – Yayoi period, introduction of rice agriculture and metallurgy

- ca. 300–750 CE – Kofun period, rise of centralized authority and Yamato clan; emergence of Confucianism

- 538–794 CE – Asuka and Nara periods, introduction of Buddhism and state formation

- 794–1185 CE – Heian period, flourishing of Japanese culture and rise of samurai influence

- 1185–1573 – Kamakura and Muromachi periods, establishment of shogunate and feudal Japan

- 1573–1600 – Azuchi-Momoyama period, unification of Japan and contact with Europeans

- 1600–1868 – Edo period, isolation and cultural growth under Tokugawa shogunate

- 1868–1912 – Meiji period, modernization and industrialization

- 1912–1945 – Taisho and Showa periods, expansion and World War II

- 1945–1989 – Postwar Japan, recovery and economic boom

- 1989–present – Heisei and Reiwa periods, contemporary Japan

Conclusion

The history of Japanese civilization is a remarkable story of continuity, adaptation, and cultural synthesis. From the hunter-gatherer societies of the Jomon period to the highly modernized nation of today, Japan has undergone profound transformations while maintaining a distinct cultural identity. Each era brought unique contributions, from the early development of pottery and metallurgy to the rise of a feudal society dominated by the samurai, and eventually to the establishment of a modern industrial state.

Throughout its history, Japan has drawn inspiration from its neighbors, in particular China and Korea, while cultivating a unique path of development. The introduction of Buddhism, Confucianism, and later Western technologies enriched its society without eroding its indigenous traditions. Despite periods of isolation and conflict, Japan emerged as a global leader in culture, technology, and innovation.

Understanding Japan’s historical trajectory provides insight into how a civilization can balance tradition and modernization. As Japan continues to navigate contemporary challenges, its rich history offers valuable lessons on resilience, adaptation, and cultural preservation.

References

- Junko Habu, Ancient Jomon of Japan, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521776707

- Yoshinori Yasuda, Jomon Reflections: Forager Life and Culture in the Prehistoric Japanese Archipelago, 2005, Oxbow Books, ISBN: 978-1842170885

- Richard Pearson, Archaeology of the Ryukyu Islands: An Early Jomon Perspective, 2019, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824873783

- Simon Kaner, The Power of Dogu: Ceramic Figures from Ancient Japan, 2009, British Museum Press, ISBN: 978-0714124643

- Koji Mizoguchi, The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State, 2018, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521711883

- Gerard Joseph Groot, The Prehistory of Japan, 2013, Literary Licensing, LLC, ISBN: 978-1258663018

- Mark Hudson, Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands, 1999, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824821562

- Wikipedia article on Jomon cultureꜛ

comments