Jainism: Peaceful path to liberation

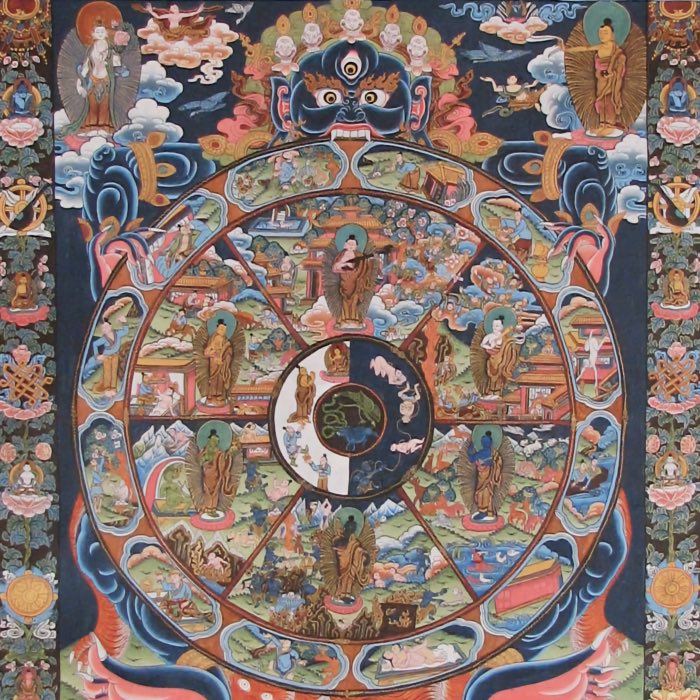

Jainism is one of the most ancient religious and philosophical traditions of India, with roots that extend back to the 6th century BCE or earlier. Founded by Mahāvīra (599–527 BCE), the 24th Tīrthaṅkara (spiritual teacher), Jainism emerged as part of the Śramaṇa movement, which challenged the ritualistic orthodoxy of Vedic religion and proposed alternative paths to spiritual liberation (mokṣa). Jain philosophy emphasizes rigorous ethics, asceticism, and non-violence (ahiṃsā) as means to purify the soul and achieve liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra). This article briefly explores the historical development, key philosophical concepts, ethical principles, and practices of Jainism.

Jain miniature painting of 24 tirthankaras, Jaipur, c. 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical origins and the Tīrthaṅkara tradition

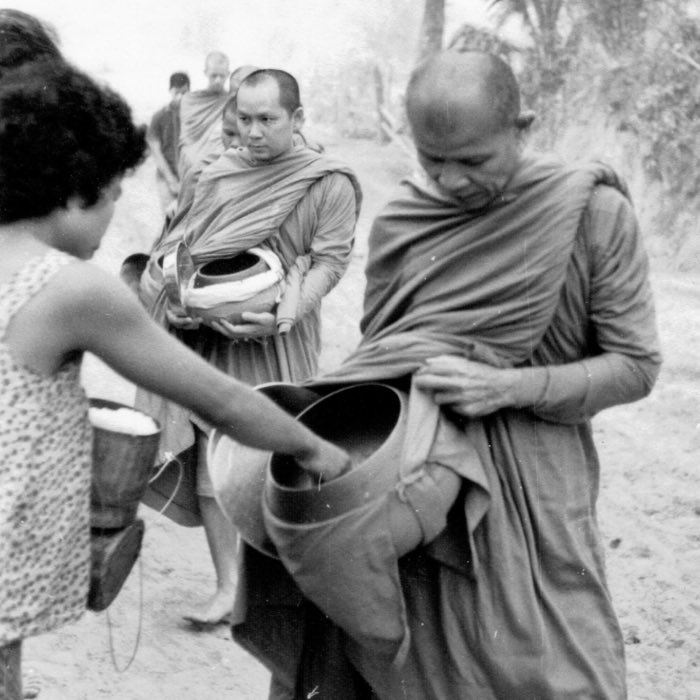

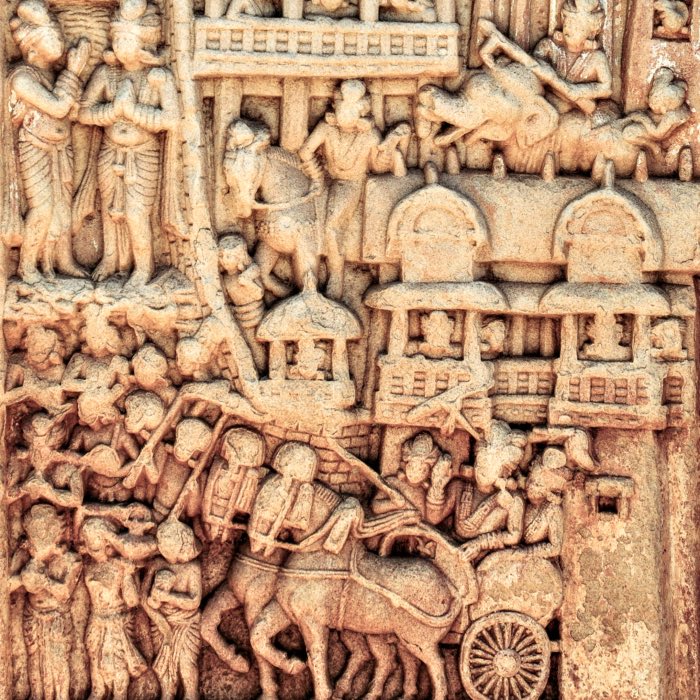

The historical origins of Jainism are closely associated with the life and teachings of Mahāvīra, who is traditionally regarded as the founder of the present Jain order. However, Jainism holds that Mahāvīra was preceded by 23 Tīrthaṅkaras, or spiritual teachers, the first of whom was Ṛṣabha. The Tīrthaṅkaras are believed to have revitalized the Jain path at various times, guiding individuals toward liberation.

Ṛṣabha (or Rishabha, Rishabhanatha, Ikshvaku) is believed to have lived over a million years ago. He is considered the founder of Jain religion in the present time cycle. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The early Jain community grew in the kingdoms of Magadha and Kosala, regions where other śramaṇa traditions, such as Buddhism, also flourished. Jainism initially spread through ascetic wanderers who lived strict lives of renunciation and preached its core teachings to lay followers.

Key philosophical concepts

Jain philosophy is dualistic, distinguishing between the sentient self (jīva) and insentient matter (ajīva). Unlike other Indian traditions, Jainism rejects the notion of a creator god and posits an eternal universe governed by natural laws. Some of the key philosophical concepts in Jainism include:

Jīva and ajīva

The soul, or jīva, is a conscious, eternal, and indestructible entity. Every living being possesses a soul, which is inherently pure but becomes entangled with karma through actions and desires.

Everything that is not conscious, such as matter, time, space, and motion, falls under the category of ajīva (non-soul). Interaction between jīva and ajīva gives rise to the empirical world.

Karma as a material substance

Unlike other Indian philosophical systems that view karma as a moral law, Jainism conceives of karma as a fine, imperceptible form of matter that binds to the soul due to passions and actions. This karmic matter obscures the soul’s inherent qualities of infinite knowledge, perception, bliss, and energy.

Liberation (mokṣa) is achieved by purging all karma through asceticism and ethical conduct, allowing the soul to regain its pure, luminous state.

Anekāntavāda (doctrine of multiple viewpoints)

Anekāntavāda is a central tenet of Jain epistemology, emphasizing that reality is complex and can be perceived from multiple perspectives. Jain philosophy asserts that no single viewpoint can capture the entirety of truth. This doctrine fosters intellectual humility and non-absolutism in philosophical discourse.

Syādvāda (conditional predication)

Closely related to anekāntavāda, syādvāda is the Jain theory of conditional predication. It holds that any statement about reality is only conditionally true, depending on the context. According to syādvāda, every proposition should be qualified by the term syāt (“in some respect”), reflecting the complexity of reality.

Naya-vāda (doctrine of partial viewpoints)

Naya-vāda complements anekāntavāda and syādvāda by proposing that every judgment or statement represents only a partial viewpoint (naya). Understanding multiple nayas leads to a more comprehensive grasp of reality.

Ethical principles in Jainism

Jain ethics are grounded in the goal of purifying the soul by eliminating passions and desires. The ethical code is defined by the five great vows (mahāvratas), which are observed by monks and nuns, while lay followers (śrāvakas) observe them in a more limited form (aṇuvratas).

- Ahiṃsā (non-violence): Non-violence is the foremost ethical principle in Jainism, extending not only to humans but to all living beings. Jains practice extreme forms of non-violence, including vegetarianism, careful walking, and the use of masks to prevent harming even microscopic life forms.

- Satya (truthfulness): Speaking the truth is essential, but it must be done with regard for non-violence. Jains are instructed to avoid speech that may cause harm or hurt others.

- Asteya (non-stealing): Jains must not take anything that is not willingly given. This principle includes avoiding exploitative practices.

- Brahmacarya (celibacy or chastity): Monks and nuns observe complete celibacy, while lay followers practice sexual restraint within marriage.

- Aparigraha (non-possession or non-attachment): Detachment from material possessions and relationships is crucial for spiritual progress. Monks and nuns renounce all possessions, while laypeople are encouraged to live simply and practice charity.

Jain practices and lifestyle

Asceticism

Jain monks and nuns lead extremely austere lives, following the five great vows strictly. They practice rigorous self-discipline, including fasting, meditation, and renunciation of all personal comforts. Ascetic practices are seen as essential for burning off accumulated karma and progressing toward liberation.

Meditation and fasting

meditation (dhyāna) is a key practice in Jainism, aimed at cultivating self-awareness and detachment. Jains also observe regular fasting, with some undertaking long fasts during festivals such as Paryuṣaṇa, a period of intense spiritual reflection and penance.

Worship and rituals

Although Jainism rejects the notion of a creator god, it includes devotional practices centered on the Tīrthaṅkaras. Jains worship images of the Tīrthaṅkaras as a means of expressing reverence and focusing their minds on the ideals of purity and detachment.

Paths to liberation

Jainism outlines three interrelated paths to liberation, collectively known as the Three Jewels (ratnatraya):

- Right faith (samyak-darśana): Having faith in the teachings of the Tīrthaṅkaras and the Jain philosophy.

- Right knowledge (samyak-jñāna): Gaining correct understanding of reality, free from doubt and delusion.

- Right conduct (samyak-cāritra): Living a life of ethical discipline and asceticism, in accordance with the five great vows.

Only by following all three paths can an individual attain mokṣa, the state of perfect liberation.

Jainism’s influence and legacy

Jainism has had a profound influence on Indian philosophy, art, and culture. Its emphasis on ahiṃsā influenced leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, who adopted non-violence as a core principle in his struggle for Indian independence. Jain contributions to logic, epistemology, and ethics have enriched the broader philosophical discourse in India.

Jainism also played a significant role in the development of Indian art and architecture, as evidenced by the magnificent Jain temples at Mount Abu, Shravanabelagola, and Palitana.

Conclusion

Jainism represents a unique spiritual tradition that emphasizes rigorous ethics, asceticism, and intellectual inquiry as means to attain liberation. By rejecting ritualism and advocating non-violence and self-discipline, it provided an alternative path to spiritual fulfillment in ancient India. Evolved in an era along with other śramaṇa traditions such as Buddhism and Ājīvika, Jainism remained a vivid and influential tradition that continues until the present day.

References and further reading

- Paul Dundas, The Jains, 2002, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415266062

- Padmanabh S. Jaini, The Jaina path of purification, 2001, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120815780

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- Kristi Wiley, Historical dictionary of Jainism, 2004, Scarecrow Press, ISBN: 978-0810850514

comments