Indian philosophy: An overview of ancient schools and concepts

Ancient Indian philosophy encompasses a vast and diverse body of knowledge, addressing fundamental questions about the nature of reality, self, knowledge, ethics, and liberation. Unlike many other philosophical traditions, Indian philosophy has a deeply practical orientation, with most schools concerned not merely with abstract speculation but with guiding individuals toward spiritual liberation (mokṣa). This post sketches a brief overview of the philosophical landscape of ancient India, structuring the topics covered in the major schools of thought and their core doctrines.

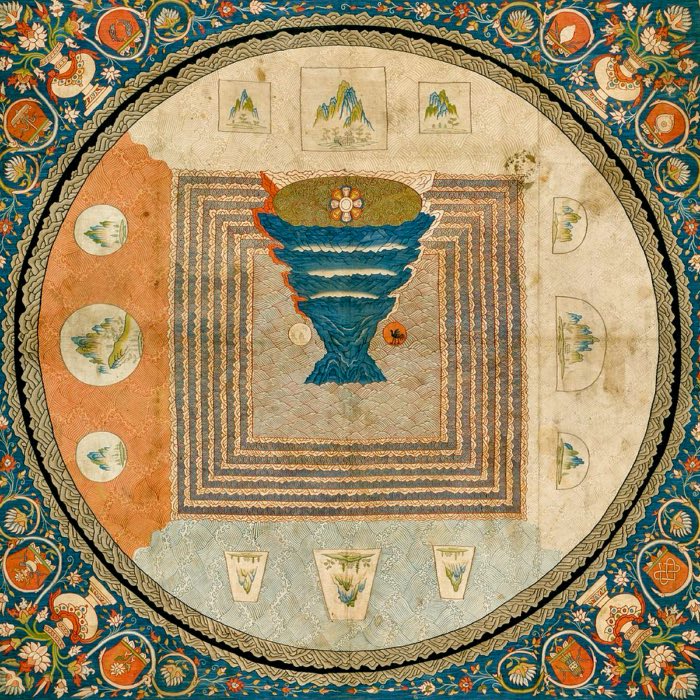

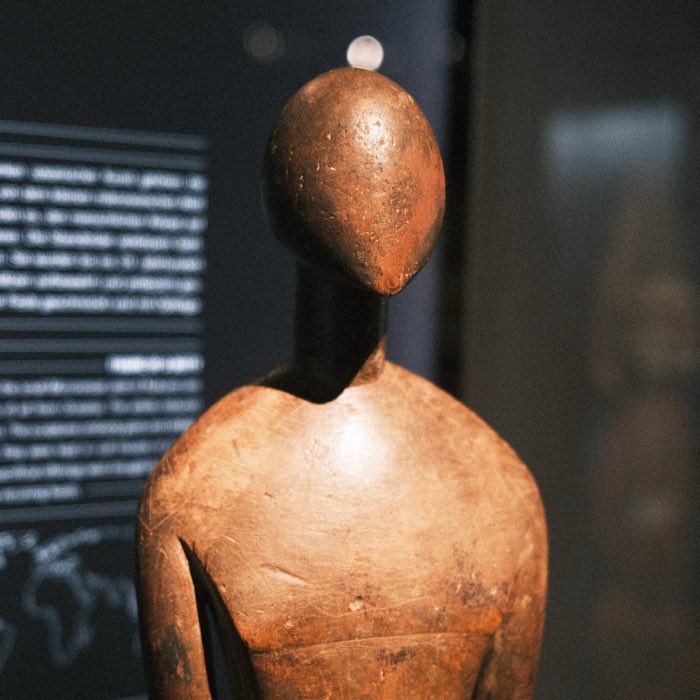

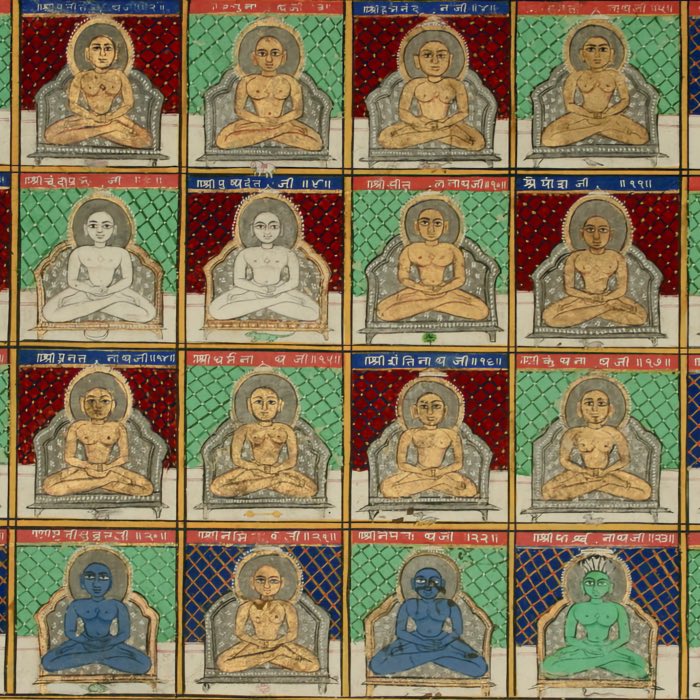

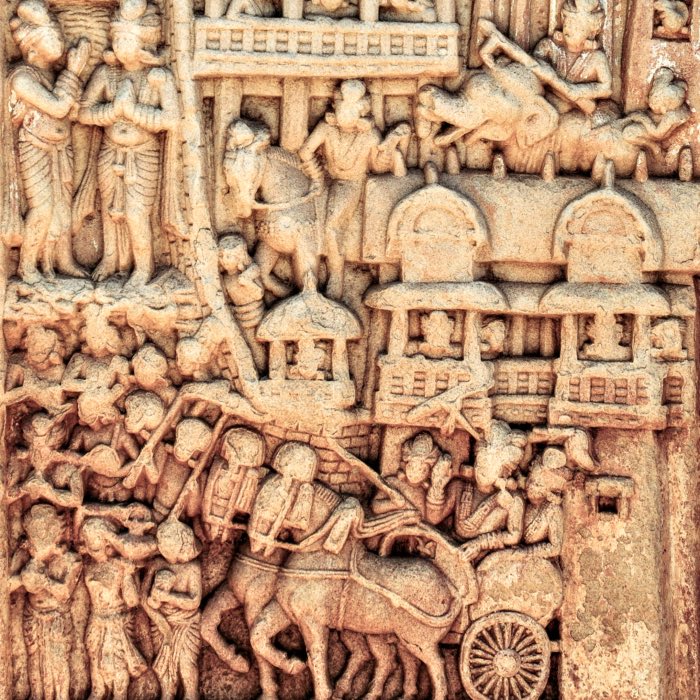

A statue of Parshvanatha, the 23rd of 24 Tirthankaras (Ford-Maker of Dharma) of Jainism., sandstone, ca. 600 CE, Uttar Pradesh, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Vedic tradition: The foundation of Indian philosophy and the emergence of Hinduism

The earliest philosophical ideas in India can be traced to the Vedas, the oldest religious texts composed between 1500 and 500 BCE. Initially focused on rituals (karma) and cosmic order (ṛta), Vedic thought evolved over time, particularly in the Upanishads (circa 800–300 BCE). The Upanishads marked a shift from ritualism to philosophical inquiry, introducing key concepts such as:

- Brahman: The ultimate, unchanging reality underlying the universe.

- Ātman): The individual self, which is ultimately identical to brahman in Vedantic thought.

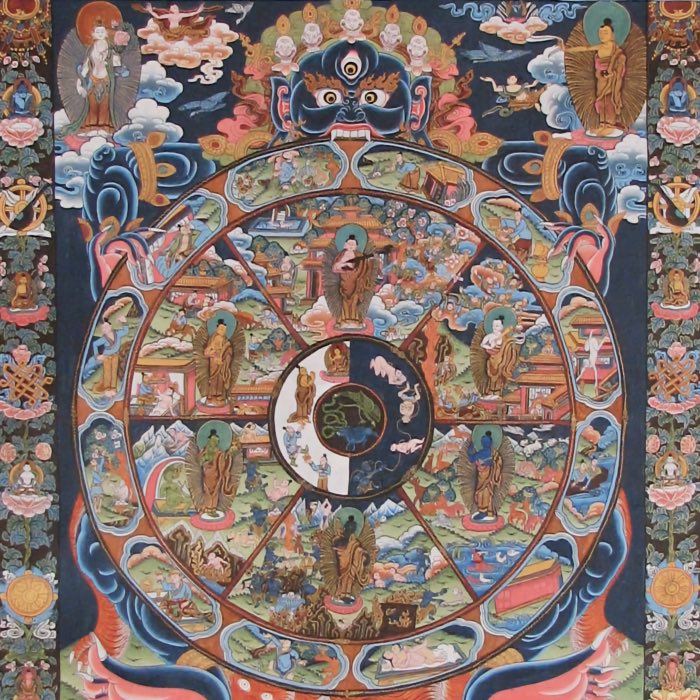

- Karma and samsāra: The law of moral causality and the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

- Mokṣa: Liberation from the cycle of samsāra through self-realization and knowledge.

These Upanishadic ideas laid the intellectual foundation for later philosophical schools, particularly Vedanta, Sāṁkhya, and Yoga, while also influencing heterodox traditions like Jainism and Buddhism. The philosophical inquiries of the Upanishads catalyzed a broader engagement with metaphysics, ethics, and the nature of consciousness across Indian philosophical traditions.

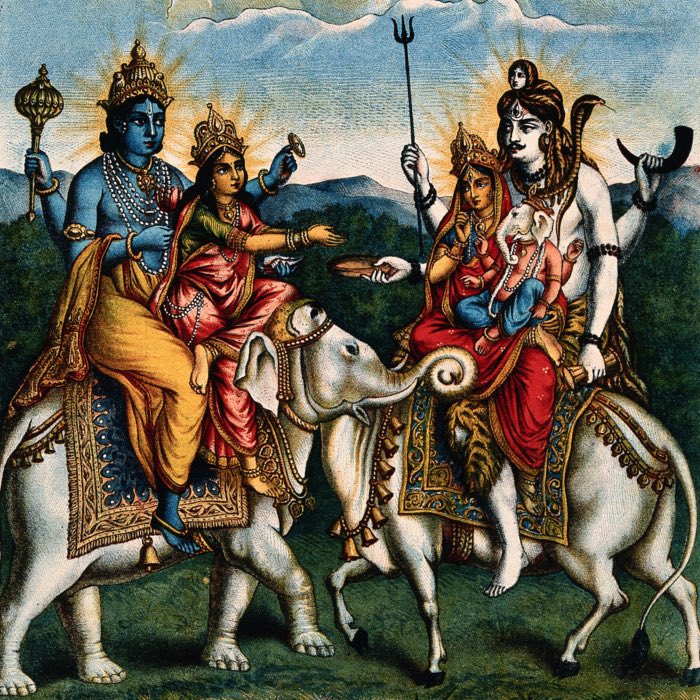

The Vedic tradition, encompassing both ritual practices and philosophical inquiry, also forms the foundation of Hinduism. Over centuries, Hinduism absorbed various philosophical schools and practices, giving rise to a diverse range of spiritual paths. Vedanta became central to Hindu philosophical thought, focusing on the relationship between brahman and ātman), and offering multiple interpretations through schools like Advaita, Viśiṣṭādvaita, and Dvaita. Sāṁkhya and Yoga, with their dualistic cosmology and emphasis on disciplined practice, provided both theoretical frameworks and practical methods for attaining liberation. Alongside these philosophical systems, Bhakti traditions emerged, emphasizing love, devotion, and surrender to a personal deity, such as Viṣṇu, Śiva, or the Goddess. These devotional movements offered an accessible spiritual path, often independent of complex philosophical inquiry.

Hinduism’s openness to diverse perspectives enabled it to integrate a wide range of philosophical and spiritual ideas, making it one of the most pluralistic religious traditions in the world. Its strength lies in its ability to stand at the intersection of ritual, philosophy, and devotion, offering paths suited to seekers with varied temperaments and aspirations.

The Śramaṇa movement: A challenge to Vedic orthodoxy

Parallel to the Vedic tradition, the Śramaṇa movement emerged as an alternative intellectual and spiritual current. This movement, which includes Jainism, Buddhism, and the now-extinct Ājīvika school, rejected the authority of the Vedas and ritual sacrifices, emphasizing personal effort, ethical conduct, and ascetic practices as the means to liberation.

- Jainism: Founded by Mahāvīra, Jainism emphasizes rigorous asceticism, non-violence (ahiṃsā), and the purification of the soul through ethical conduct and meditation. Jain philosophy is dualistic, positing a distinction between the conscious soul (jīva) and insentient matter (ajīva).

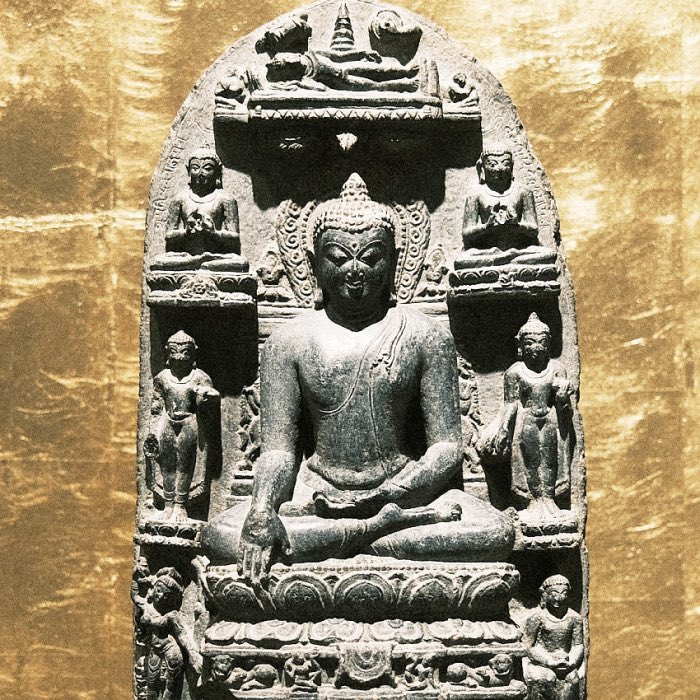

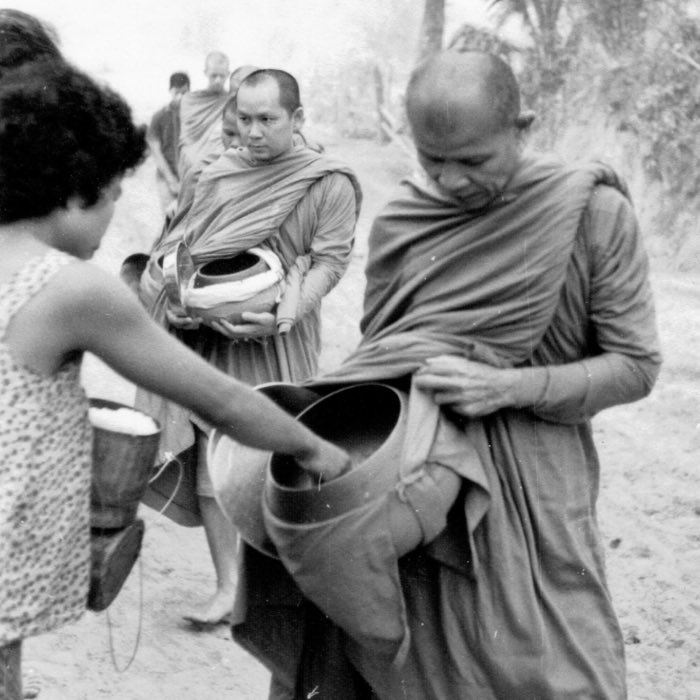

- Buddhism: Founded by Gautama Buddha, Buddhism introduced a radically new approach by rejecting the notion of a permanent self (ātman)) and focusing on the impermanence (anicca) of all phenomena. Central to Buddhist thought are the Four Noble Truths, which explain the nature of suffering (dukkha) and the path to its cessation through the Eightfold Path.

The Śramaṇa movement played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual environment of ancient India, influencing even the orthodox schools of thought.

The orthodox schools of Indian philosophy

The orthodox schools (āstika) of Indian philosophy accept the authority of the Vedas, but they developed distinct metaphysical and epistemological systems. These schools are traditionally classified into six darśanas (viewpoints):

Sāṃkhya: Dualism of puruṣa and prakṛti

Sāṃkhya, one of the oldest philosophical systems, presents a dualistic cosmology that distinguishes between:

- Puruṣa: The passive, conscious self or spirit.

- Prakṛti: The active, unconscious material principle.

Liberation in Sāṃkhya is achieved through knowledge of the distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti, leading to the cessation of suffering. Sāṃkhya’s dualism influenced both the Yoga school and early Buddhist thought.

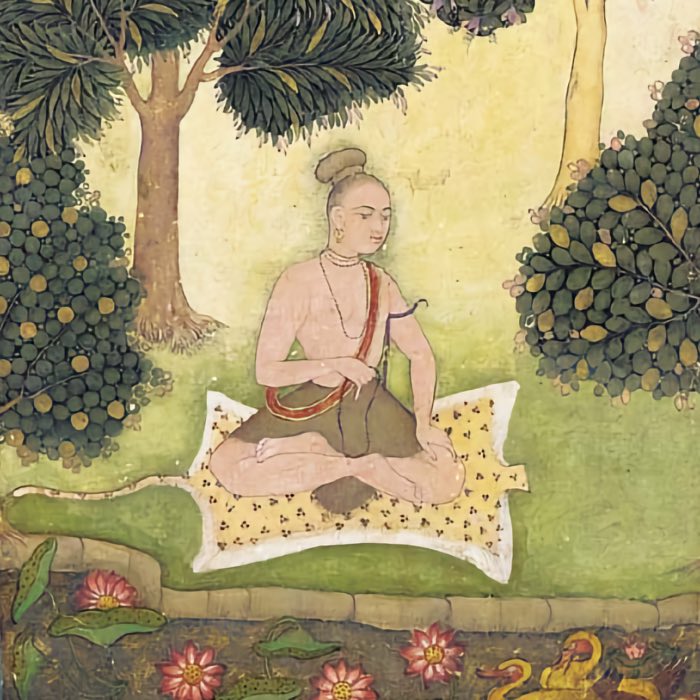

Yoga: Practical discipline for liberation

Closely related to Sāṃkhya, Yoga, as systematized by Patañjali in the Yoga Sutras, emphasizes disciplined practice (sādhana) as the means to liberation. Patañjali outlines an Eightfold Path (aṣṭāṅga yoga) that includes ethical principles, physical postures (āsana), breath control (prāṇāyāma), and meditation (dhyāna). While Sāṃkhya provides a theoretical framework, Yoga offers practical methods for achieving spiritual freedom.

Vedanta: Inquiry into the nature of brahman and ātman

Vedanta focuses on the philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, particularly concerning the relationship between brahman (ultimate reality) and ātman) (self). The three principal schools of Vedanta are:

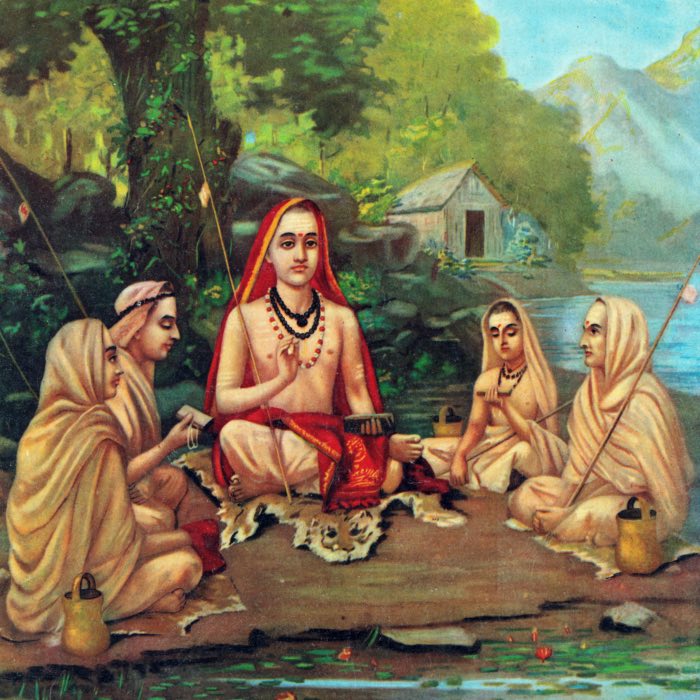

- Advaita Vedanta (non-dualism): Ādi Śaṅkara’s school teaches that brahman alone is real, and the world is an illusion (māyā). Liberation involves realizing the identity of ātman) and brahman.

- Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta (qualified non-dualism): Rāmānuja’s school holds that while brahman is the ultimate reality, individual selves are distinct yet dependent parts of brahman. Liberation involves eternal communion with God.

- Dvaita Vedanta (dualism): Madhva’s school posits a strict dualism between brahman (God) and individual selves, emphasizing devotion (bhakti) as the means to liberation.

Nyāya: logic and epistemology

The Nyāya school focuses on logic and epistemology, offering a rigorous analysis of valid means of knowledge (pramāṇas), including perception, inference, comparison, and testimony. Nyāya’s logical methods influenced other schools, including Buddhist logic.

Vaiśeṣika: Atomism and categories of reality

The Vaiśeṣika school presents an atomistic view of the universe, proposing that all material objects are composed of indivisible atoms. It also classifies reality into six or seven categories (padārtha), such as substance, quality, and action.

Mīmāṃsā: Ritualism and the interpretation of the Vedas

The Mīmāṃsā school is primarily concerned with the correct interpretation of Vedic rituals and the philosophy of language. Its later development, known as Vedānta, shifted the focus from ritual to metaphysics.

Key philosophical concepts

Throughout these schools, several key philosophical concepts recur, though interpreted differently by each tradition:

- Brahman and ātman: The nature of ultimate reality and the self.

- Karma and samsāra: The law of moral causality and the cycle of rebirth.

- Mokṣa: Liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

- Māyā: The illusion of the empirical world, central to Advaita Vedanta.

- Ahiṃsā: Non-violence, a core ethical principle in Jainism and Buddhism.

- Anatta: The Buddhist doctrine of non-self, rejecting the Upanishadic concept of ātman).

Indian philosophy in comparison with classical Greek and Chinese philosophy

Ancient Indian philosophy, with its emphasis on metaphysics, ethics, and liberation, can be meaningfully compared with classical Greek and Chinese philosophical traditions. While these three intellectual cultures developed independently, they addressed similar fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, and the good life, albeit with different emphases and methodologies.

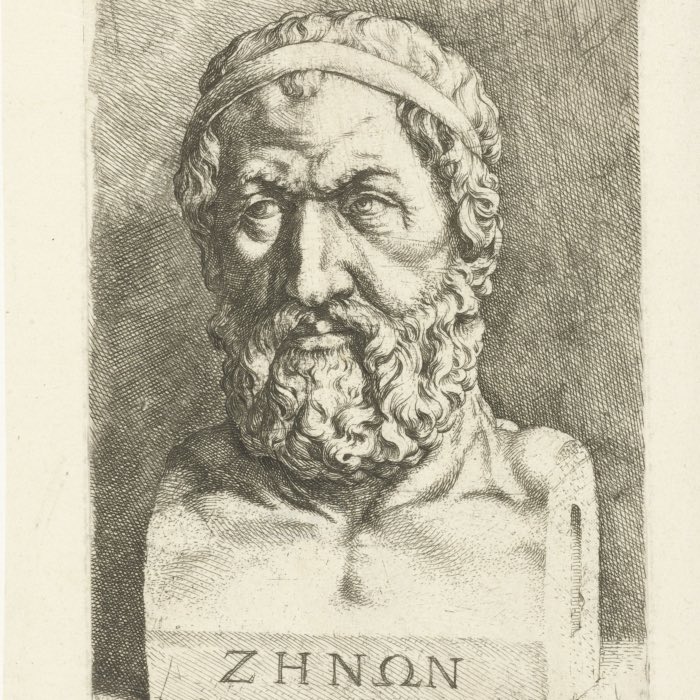

In classical Greek philosophy, particularly in the works of Plato and Aristotle, the focus was on understanding the nature of reality, virtue, and the rational mind. Greek thinkers were primarily concerned with the pursuit of knowledge through reason and logic. Unlike Indian philosophy, which often aimed at spiritual liberation (mokṣa), Greek philosophy emphasized rational inquiry as a means to achieve wisdom and ethical living. However, similarities can be found in the metaphysical speculations of Plato’s theory of forms and the Upanishadic concept of brahman as the ultimate reality.

Chinese philosophy, particularly Confucianism and Daoism, prioritized social harmony, ethics, and the balance of natural forces. Confucianism focused on moral conduct and proper governance, while Daoism emphasized living in harmony with the Dao, the fundamental principle underlying the universe. Compared to Indian philosophy, which often delved deeply into metaphysical and psychological analyses, Chinese philosophy maintained a more practical orientation, seeking balance and order in both individual and societal life.

Despite their differences, all three traditions shared a commitment to exploring the nature of existence and the human condition. The dialogues and debates within each tradition enriched their respective intellectual landscapes and continue to inspire philosophical inquiry worldwide.

Conclusion

Ancient Indian philosophy offers a remarkably diverse range of perspectives on fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, and liberation. By engaging in dialogue and debate, these schools enriched the intellectual and spiritual landscape of India, influencing each other in profound ways. While some schools emphasized the pursuit of knowledge and self-realization, others focused on ethical conduct, ritual practice, or devotion to a personal deity.

Overall, India has developed a rich philosophical tradition over time, characterized by its practical orientation, metaphysical depth, and ethical insights. Many of today’s largest religious and philosophical traditions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, trace their roots back to the ancient philosophical inquiries of the Vedic and Śramaṇa traditions, testifying the enduring impact of Indian thought on global intellectual history.

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- Gethin, R., The Foundations of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192892232

- Johannes Bronkhorst, Greater Magadha: Studies in the culture of early India, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359663975

- R. Puligandla, Fundamentals of Indian philosophy, 1997, D.K. Printworld, ISBN: 978-8124600863

- Jamison, S. W., & Brereton, J. P., The Rigveda: the earliest religious poetry of India, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199370184

- Gonda, J., Vedic ritual: the non-solemn rites, 1997, Brill, ISBN: 978-9004062108

- Olivelle, P., The early Upanishads: annotated text and translation, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195124354

comments