The emergence of Buddhism in India: A revolutionary new path to liberation

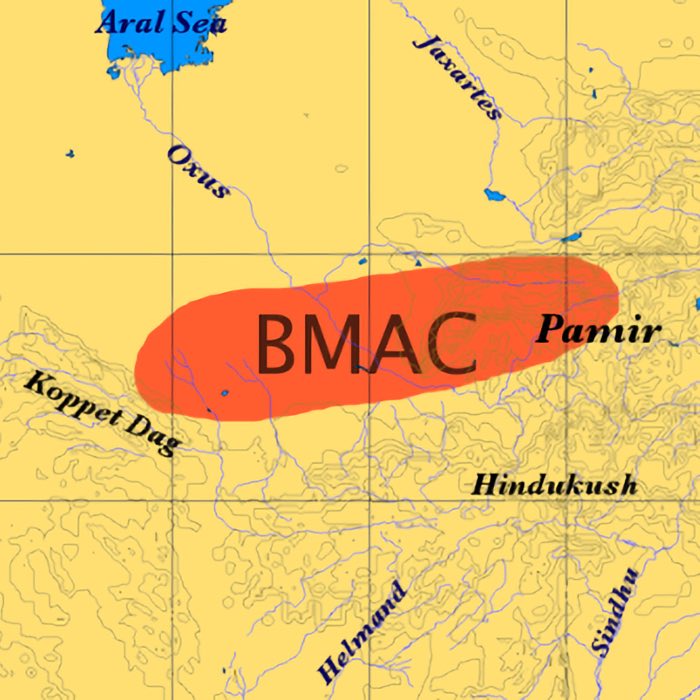

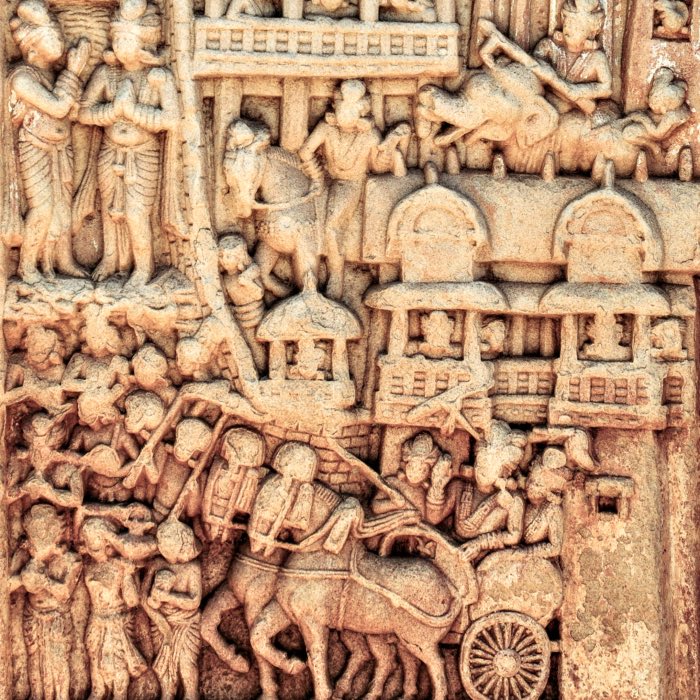

Buddhism emerged in the 6th century BCE in ancient India during a period of significant social, economic, and intellectual transformation. This era, known as the second urbanization, saw the rise of cities, trade networks, and new forms of governance, leading to a questioning of traditional Vedic rituals and societal hierarchies. Philosophically, it was a time of rich debate, with various schools of thought offering different paths to liberation (mokṣa) from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra; also see this post). The Śramaṇa movement, which included Jainism, Ājīvika, and other ascetic traditions, played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual environment in which Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, developed his teachings. In this post, we take a brief look at the historical context of Buddhism’s emergence and its engagement with existing philosophical concepts in ancient India.

Rock-cut Buddha Statue at Bojjanakonda near Anakapalle of Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical context: The second urbanization and the Śramaṇa movement

The period of the second urbanization, from 600 to 300 BCE, was a transformative era in ancient India marked by significant social, political, and economic changes. The rise of powerful kingdoms such as Magadha and Kosala, along with expanding urban centers like Rājagṛhā and Vārāṇasī, fostered trade, wealth accumulation, and centralized governance. This disrupted the traditional agrarian society that had long supported Vedic ritualism and led to growing skepticism about established rituals and caste-based hierarchies.

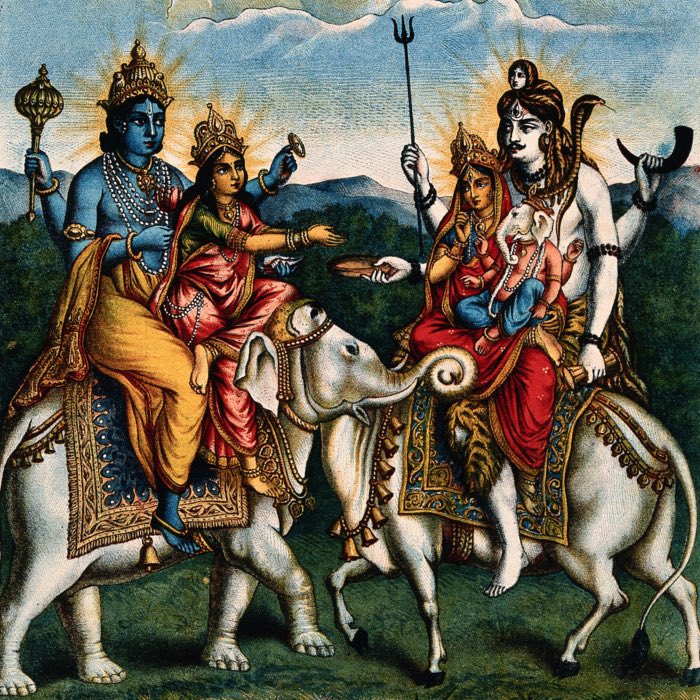

The urban environment encouraged intellectual discourse and spiritual inquiry, resulting in the emergence of diverse schools of thought addressing fundamental questions about life, suffering, and liberation. In this context, the Śramaṇa movement arose as a direct challenge to Vedic orthodoxy. Unlike the ritual-centric Vedic tradition, which relied on sacrifices (yajña) performed by Brahmins, the śramaṇa traditions advocated for individual effort, asceticism, and ethical living as paths to liberation.

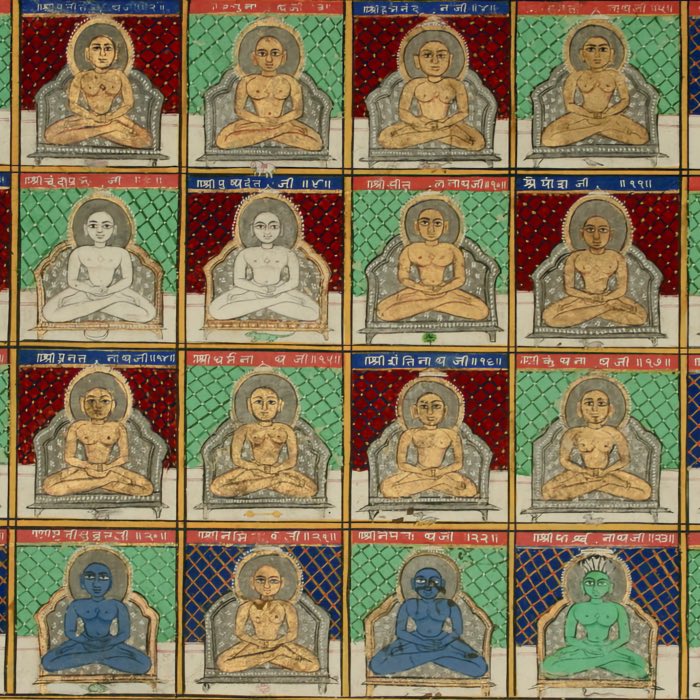

Prominent heterodox schools within the śramaṇa movement included Jainism, Ājīvika, and early forms of Yoga. Jainism, led by Mahāvīra, emphasized non-violence (ahiṁsā) and severe asceticism. The Ājīvika school, founded by Makkhali Gosāla, proposed a deterministic view of existence, asserting that fate (niyati) governs all events. Early Yoga schools, closely linked to Sāṁkhya philosophy, developed meditative practices aimed at spiritual realization and liberation.

Unlike Vedic ritualism, the śramaṇa traditions emphasized renunciation, meditation, and ethical conduct, which resonated with many in the growing urban centers where Vedic authority was increasingly questioned. The egalitarian approach of the śramaṇa movement, rejecting rigid caste distinctions, further enhanced its appeal across different social classes.

It was within this dynamic intellectual environment that Gautama Buddha formulated his teachings. Drawing from śramaṇa ideas, the Buddha introduced a unique path to liberation that avoided both extreme asceticism and indulgence. His “Middle Way” advocated for balanced spiritual practice through ethical conduct, meditation, and wisdom. The Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path provided a practical framework for attaining liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth (saṃsāra), distinguishing Buddhism from other contemporary schools.

The second urbanization and the rise of the śramaṇa movement thus created the conditions for the emergence of Buddhism as a revolutionary spiritual path. By reinterpreting and engaging with prevailing philosophical ideas, Buddhism not only challenged Vedic orthodoxy but also enriched the philosophical diversity of ancient India.

Engagement with existing philosophical concepts

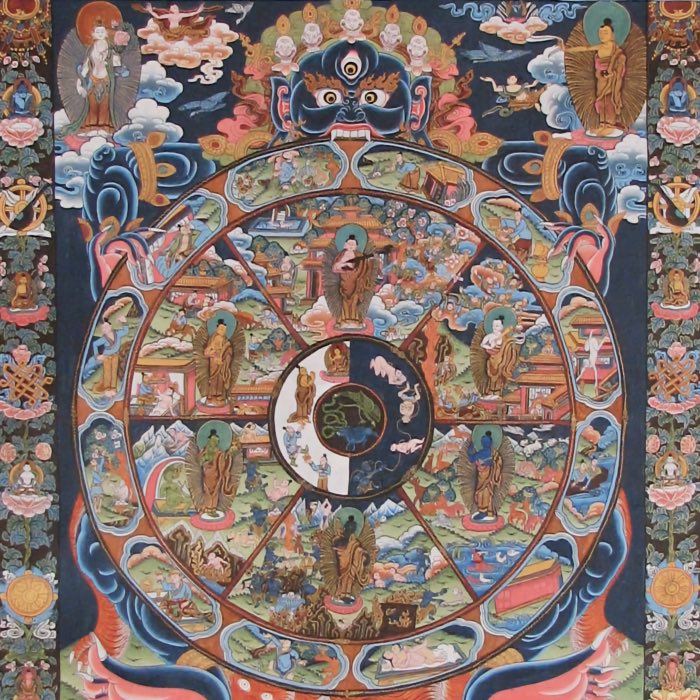

Karma and samsāra

The concepts of karma (action and its consequences) and samsāra (the cycle of rebirth) were already well-established in Vedic and śramaṇa thought. The Vedas initially described karma in the context of ritual action, while the Upanishads and the śramaṇa traditions extended it to include moral actions that determine one’s future rebirths.

Buddhism adopted the framework of karma and samsāra but reinterpreted them in significant ways:

- Buddhist view of karma: While Jainism viewed karma as a material substance binding the soul, Buddhism understood karma as volitional action driven by intention (cetanā). The Buddha emphasized that it is not merely action but the intention behind the action that generates future consequences.

- Samsāra and liberation: Like other śramaṇa schools, Buddhism viewed samsāra as a state of suffering (dukkha) from which one must escape. However, Buddhism proposed a unique path to liberation through the cessation of desire (tṛṣṇā) and ignorance (avidyā), culminating in nirvāṇa — a state beyond birth and death.

Ātman and anatta (non-self)

The Upanishads, particularly those associated with Vedanta, developed the idea of ātman as the eternal, unchanging self that is identical to brahman, the ultimate reality. Liberation (mokṣa) in this framework involved realizing the unity of ātman and brahman.

In a radical departure from Upanishadic thought, the Buddha rejected the concept of a permanent self (ātman) and introduced the doctrine of anatta (non-self):

- Anatta doctrine: The Buddha taught that what we perceive as the self is merely a collection of changing physical and mental aggregates (skandhas) — form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. Since these aggregates are impermanent (anicca) and subject to suffering (dukkha), clinging to the idea of a permanent self is the root of suffering.

- Liberation through insight: In Buddhism, liberation involves the direct realization of anatta and the impermanence of all phenomena, leading to the cessation of attachment and the attainment of nirvāṇa.

Mokṣa and nirvāṇa

While mokṣa, as understood in the Vedic and śramaṇa traditions, generally referred to liberation from samsāra and union with a higher reality (such as brahman in Vedanta or puruṣa in Sāṃkhya), the Buddha introduced a distinct concept of liberation called nirvāṇa.

- Nirvāṇa: Unlike mokṣa, which often implied eternal existence in a transcendent state, nirvāṇa in Buddhism is the cessation of all mental afflictions, desires, and ignorance. It is described as the “blowing out” of the flames of craving and suffering. The Buddha refrained from metaphysical speculation about what happens after nirvāṇa, focusing instead on the practical path to end suffering.

Dharma: From Vedic duty to Buddhist teaching

In the Vedic tradition, dharma referred to the cosmic order and the duties prescribed by one’s caste and stage of life. The Buddha redefined dharma (Dhamma in Pāli) as the universal law of nature and the teachings that lead to liberation.

Key aspects of Buddhist dharma include:

- The Four Noble Truths: The core of the Buddha’s teaching, explaining the nature of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the path to its cessation.

- The Eightfold Path: A practical guide for ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom, leading to the cessation of suffering and the attainment of nirvāṇa.

- Ethical conduct: While dharma in the Vedic sense was often tied to ritual duty, Buddhist dharma emphasized ethical conduct (śīla), including non-violence (ahiṃsā), truthfulness, and compassion.

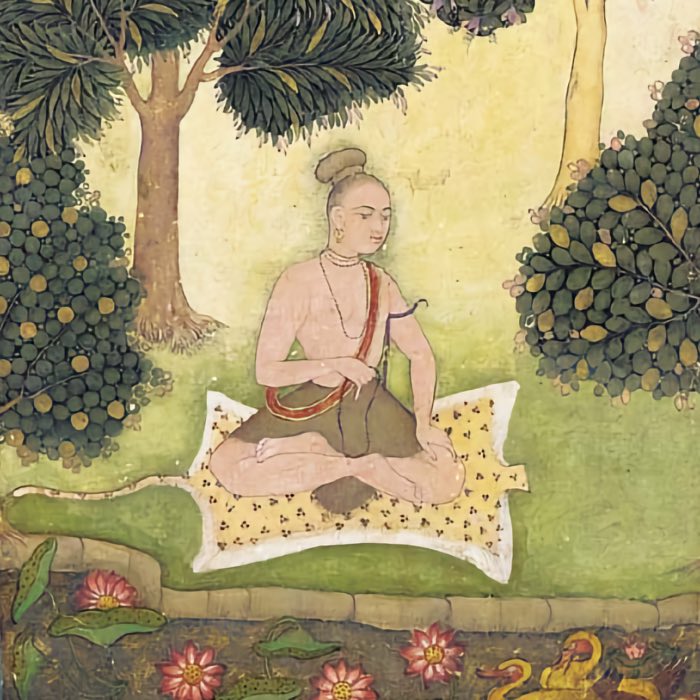

The Buddha’s Middle way: A response to extremes

The Buddha’s teachings are often characterized as the Middle Way, a path that avoids the extremes of sensual indulgence and severe asceticism. This approach was a response to two prevalent practices of his time: the ritualistic Vedic tradition, which emphasized external sacrifices and material prosperity, and the rigorous austerities practiced by some śramaṇa ascetics, who believed that self-mortification was essential for spiritual liberation. Having personally experienced both extremes — a princely life of luxury and years of harsh ascetic practices — the Buddha concluded that neither led to true enlightenment.

The Middle Way emphasizes moderation in lifestyle, ethical conduct, and mental discipline, focusing on developing wisdom and insight through meditation. This balanced approach not only offered a practical framework for achieving liberation but also made the Buddha’s teachings accessible to a wide audience, including both ascetics seeking deeper spiritual truth and laypeople striving for a meaningful life. By framing the spiritual path as one that integrates ethical living (śīla), meditative concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (prajñā), the Buddha provided a comprehensive method for overcoming suffering and attaining nirvāṇa.

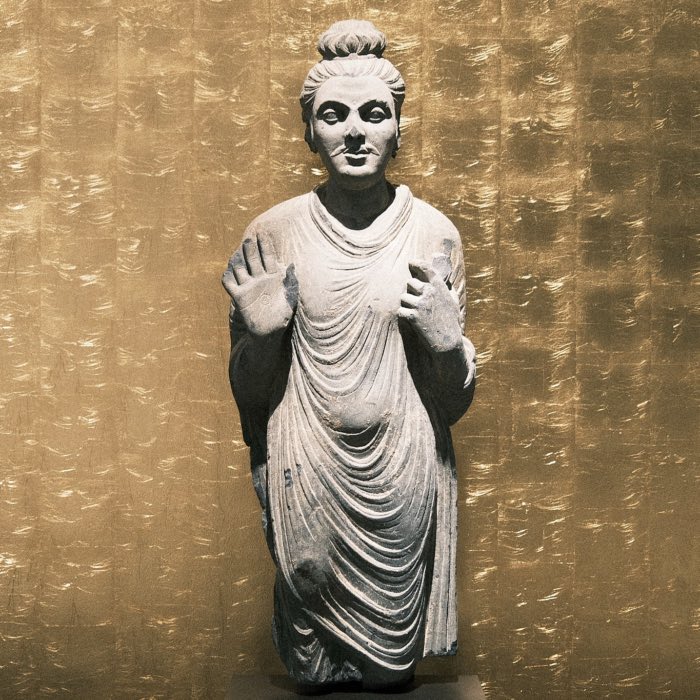

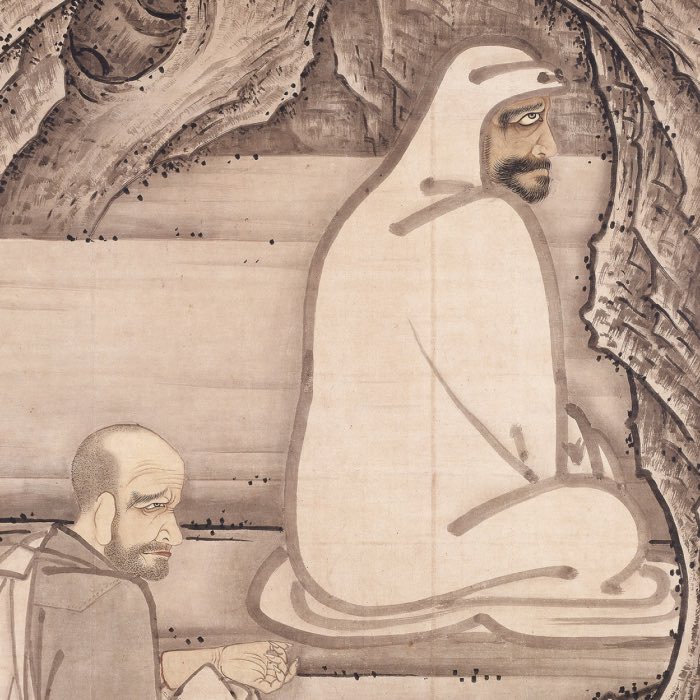

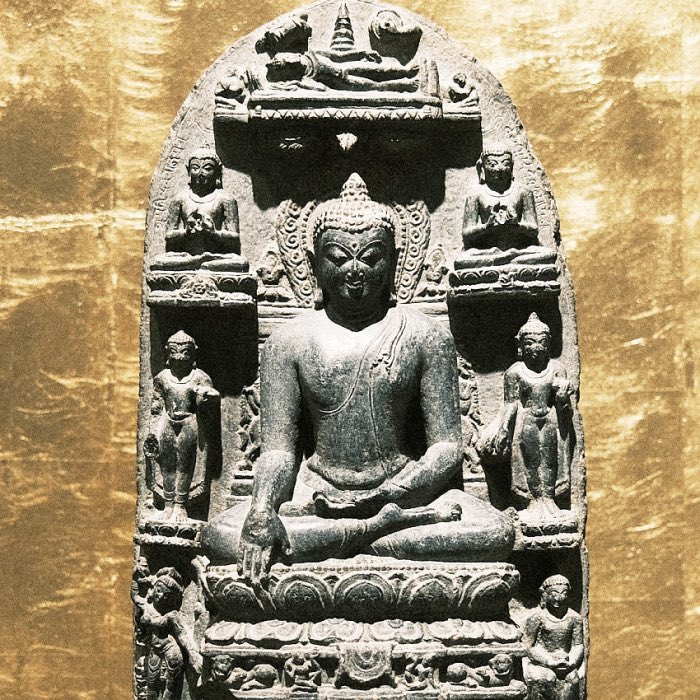

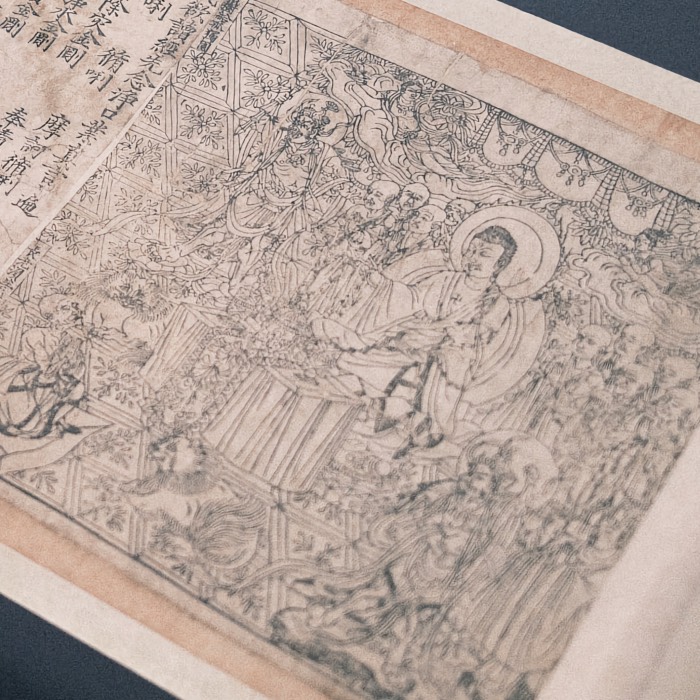

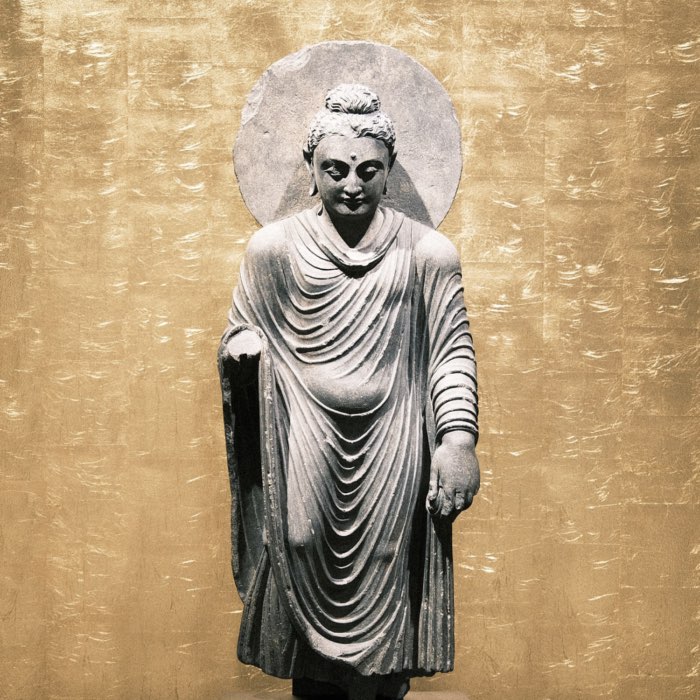

Shakyamuni Buddha in the pose of demonstrating control over the fire and water elements, Gandhara, 3rd century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Buddhism’s influence on Indian philosophy

Buddhism’s emphasis on empirical inquiry, meditation, and ethical living had a profound impact on Indian philosophy, reshaping existing traditions and inspiring new schools of thought. Its philosophical rigor and distinctive doctrines of impermanence (anicca) and non-self (anatta) challenged many of the prevailing metaphysical ideas in ancient India, leading to significant intellectual engagement and evolution.

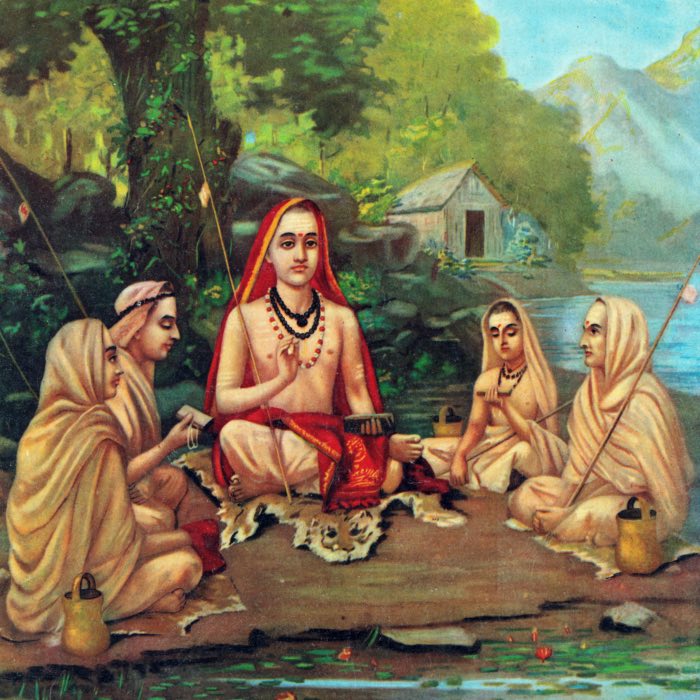

In the case of Vedanta, later schools such as Advaita Vedanta, founded by Ādi Śankara, were deeply influenced by Buddhist philosophical developments. While Vedanta upheld the concept of a permanent self (ātman) and ultimate reality (brahman), it engaged critically with Buddhist ideas, particularly regarding the nature of reality and the illusion of individuality. Śankara’s formulation of māyā (illusion) as the cause of perceiving a multiplicity of selves reflects an intellectual response to Buddhist critiques of a permanent self.

The Sāṁkhya and Yoga schools, though retaining their dualistic metaphysics of puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter), incorporated meditative practices and ethical principles that paralleled Buddhist teachings. The emphasis on disciplined practice, self-control, and detachment in Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtras demonstrates the influence of Buddhist meditative traditions. Moreover, Sāṁkhya’s detailed analysis of mental states and the causes of suffering shows a conceptual alignment with the Buddhist focus on understanding and overcoming the roots of suffering.

In the field of logic and epistemology, Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika underwent significant transformations due to the rise of Buddhist logical systems. Thinkers such as Nāgārjuna, who developed the Madhyamaka school’s doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā), and Dignāga, a pioneer in Buddhist epistemology, introduced sophisticated methods of argumentation and analysis. The rigorous debate culture fostered by Buddhist scholars compelled orthodox Hindu schools to refine their own logical frameworks. As a result, Nyāya developed an advanced system of logic, focusing on valid means of knowledge (pramāṇa) and formal reasoning, which remains a cornerstone of Indian philosophical thought.

Thus, Buddhism’s influence on Indian philosophy was multifaceted, prompting both critical engagement and adaptation. Its contributions to metaphysics, ethics, meditation, and logic not only enriched the Indian intellectual tradition but also laid the groundwork for enduring philosophical dialogues that continue to be studied and revered today.

Historical summary of Buddhism in India

Buddhism, founded by Gautama Buddha in the 6th century BCE, initially gained prominence in the region of Magadha, an area known for its vibrant intellectual activity and political significance. The Buddha’s teachings attracted followers from diverse social backgrounds, including merchants, rulers, and ordinary laypeople. The early Buddhist community (saṅgha) established monasteries and centers for learning, where the teachings were preserved and transmitted orally. Over time, several regional rulers, including King Bimbisāra of Magadha and King Prasenajit of Kosala, offered patronage to the growing Buddhist community, contributing to its spread.

Ancient kingdoms and cities of South Asia and Central Asia during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BCE): modern-day India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ancient kingdoms and cities of South Asia and Central Asia during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BCE): modern-day India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

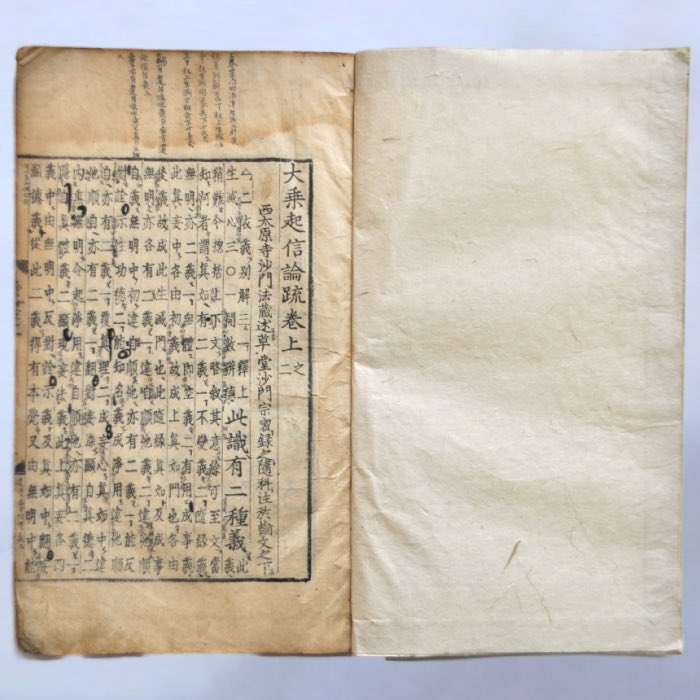

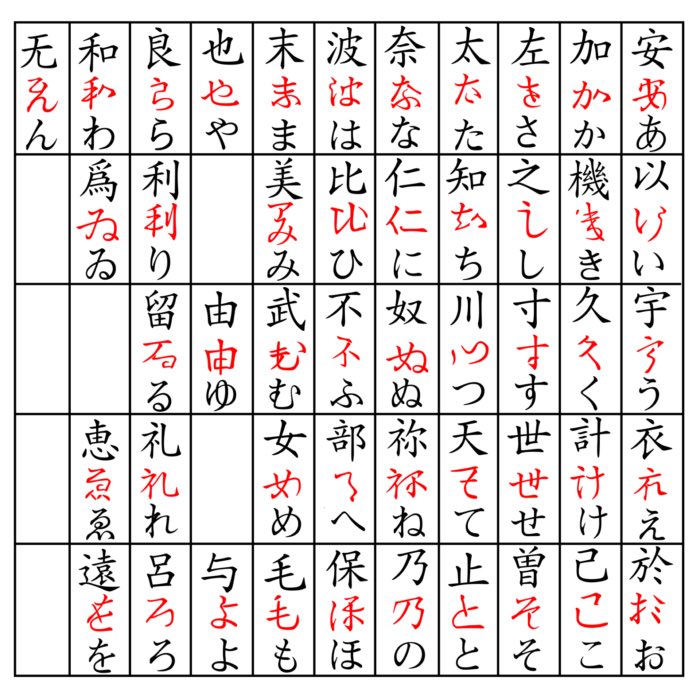

Following the Buddha’s death around 483 BCE, the First Buddhist Council was held at Rājagṛhā, where his teachings were compiled and organized into two primary collections: The Sutta Pitaka (discourses) and the Vinaya Pitaka (monastic rules). This period saw the establishment of early doctrinal foundations and the consolidation of monastic rules. Over the following century, the Buddhist community gradually expanded, attracting followers across northern India, particularly in Magadha and Kosala. Buddhist monks, supported by lay patrons, played a significant role in disseminating the teachings along emerging trade routes.

The Tripiṭaka Koreana in South Korea, an edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon carved and preserved in over 81,000 wood printing blocks. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Tripiṭaka Koreana in South Korea, an edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon carved and preserved in over 81,000 wood printing blocks. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

About a century later, around 383 BCE, the Second Buddhist Council at Vaiśālī addressed disputes regarding monastic discipline, specifically concerning the relaxation of certain rules. This council eventually led to schisms within the saṅgha, resulting in the formation of different schools, such as the Sthavira and Mahāsāṇghika. Despite these divisions, Buddhism continued to spread as itinerant monks traveled extensively across northern and central India, establishing new monastic centers and engaging with local communities.

Map of the major geographical centers of major Buddhist schools in South Asia, at around the time of Xuanzang’s visit in the 7th century CE. Red: non-Pudgalavāda Sarvāstivāda school, Orange: non-Dharmaguptaka Vibhajyavāda schools, Yellow: Mahāsāṃghika, Green: Pudgalavāda, Gray: Dharmaguptaka. The map illustrates the spread and the developed diversity of Buddhism in India at the time. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Map of the major geographical centers of major Buddhist schools in South Asia, at around the time of Xuanzang’s visit in the 7th century CE. Red: non-Pudgalavāda Sarvāstivāda school, Orange: non-Dharmaguptaka Vibhajyavāda schools, Yellow: Mahāsāṃghika, Green: Pudgalavāda, Gray: Dharmaguptaka. The map illustrates the spread and the developed diversity of Buddhism in India at the time. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

By the 4th century BCE, Buddhism had become a recognized religious tradition in several regions of India. Key urban centers like Vārāṇasī and Rājagṛhā saw flourishing Buddhist activities, with monasteries offering both spiritual guidance and education. By the time of Aśoka’s reign in the 3rd century BCE, Buddhism had already gained considerable influence and social acceptance, preparing the ground for its significant expansion under imperial patronage.

Ancient Buddhist monasteries near Dhamekh Stupa Monument Site in Sarnath. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

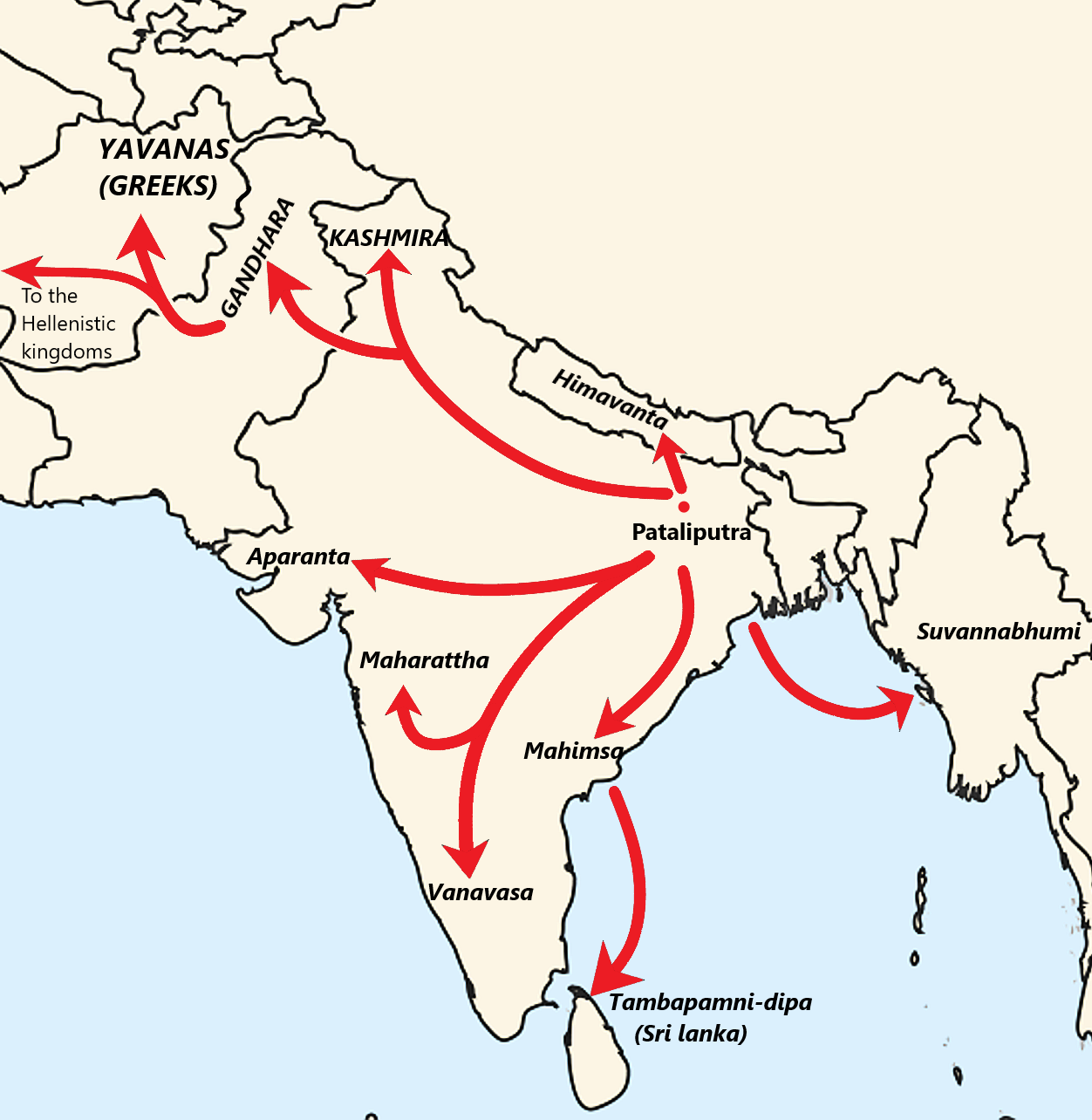

During the reign of Emperor Aśoka (r. 268–232 BCE) of the Mauryan Empire, Buddhism underwent significant expansion and institutionalization. Aśoka, after converting to Buddhism following the Kalinga War, became a key patron and supporter of the religion. He built stupas, monasteries, and pillars inscribed with edicts promoting Buddhist ethical principles across his empire. His efforts to propagate Buddhism extended beyond India, with missions sent to Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and the Hellenistic world. The Third Buddhist Council, traditionally held under Aśoka’s patronage, aimed to purify the Buddhist community and standardize the teachings.

Traditional depiction of the [Maurya Empire under Ashoka as a solid mass of Maurya-controlled territory, c. 250 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

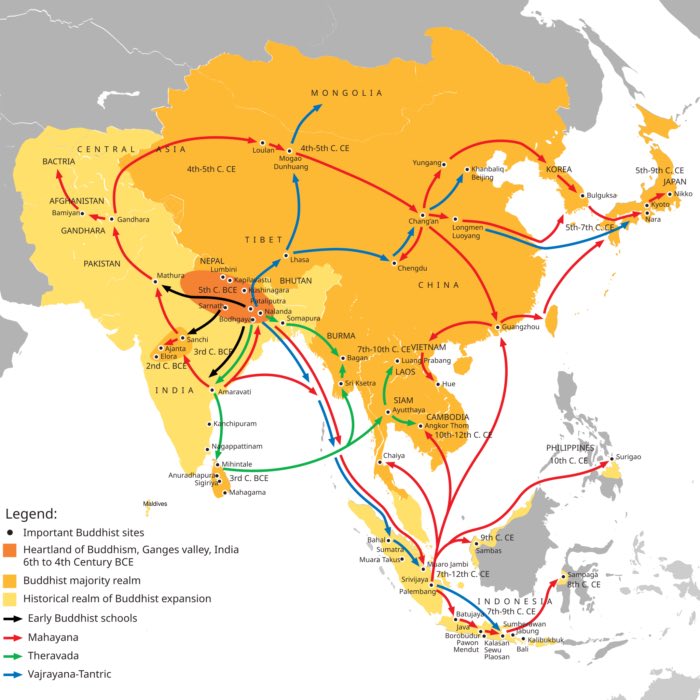

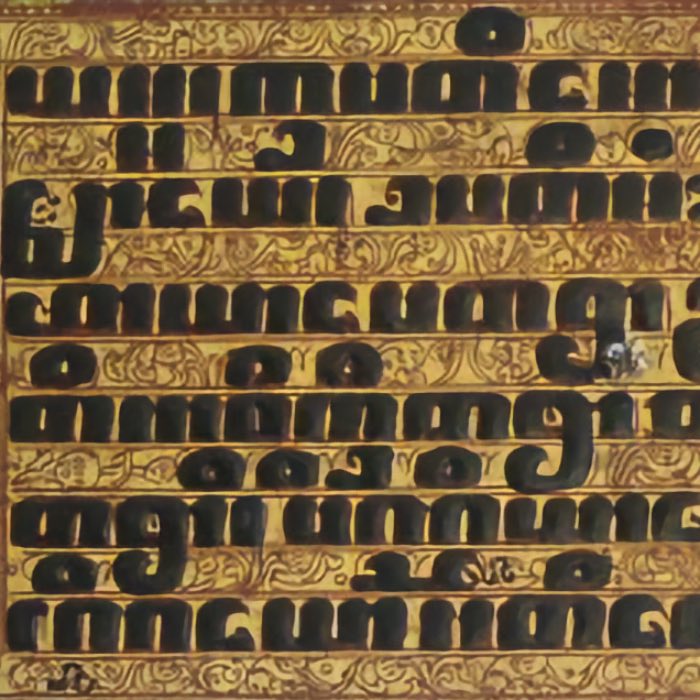

Aśoka’s missions played a crucial role in the spread of Buddhism beyond India. In Sri Lanka, Theravāda Buddhism became the dominant tradition, with Mahinda, Aśoka’s son, credited for its introduction. From Sri Lanka, it further spread to Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, where it adapted to local cultures while preserving the Pāli Canon.

Left: Map of the Buddhist missions in Asia during the reign of Ashoka. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Map of the Buddhist missions in Asia during the reign of Ashoka (broader view). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: Map of the Buddhist missions in Asia during the reign of Ashoka. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Map of the Buddhist missions in Asia during the reign of Ashoka (broader view). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

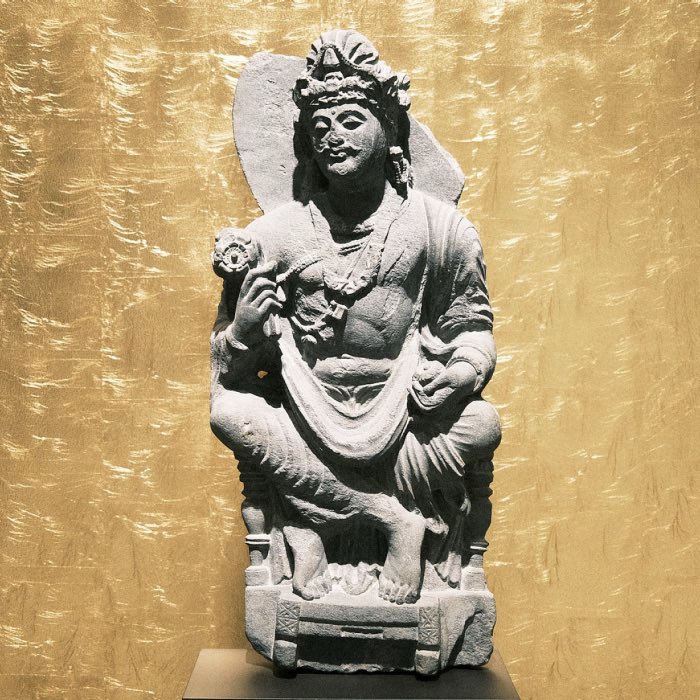

After Aśoka’s reign, Buddhism continued to flourish, particularly in the northwestern regions of India and along trade routes connecting India with Central Asia and China. In Central Asia, Buddhism traveled along the Silk Road, leading to the flourishing of communities in Gandhara and Bactria, blending with Hellenistic influences, as reflected in the Greco-Roman style of Gandharan art. Entering China during the Han dynasty, Buddhism integrated with Daoism and Confucianism, giving rise to schools like Chán (Zen). By the Tang dynasty, it was a major religious force, shaping Chinese culture.

Buddhist expansion in Asia: Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Chinese Empire (Han dynasty) through the Silk Road during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, forming what scholars have called the “great circle of Buddhism”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

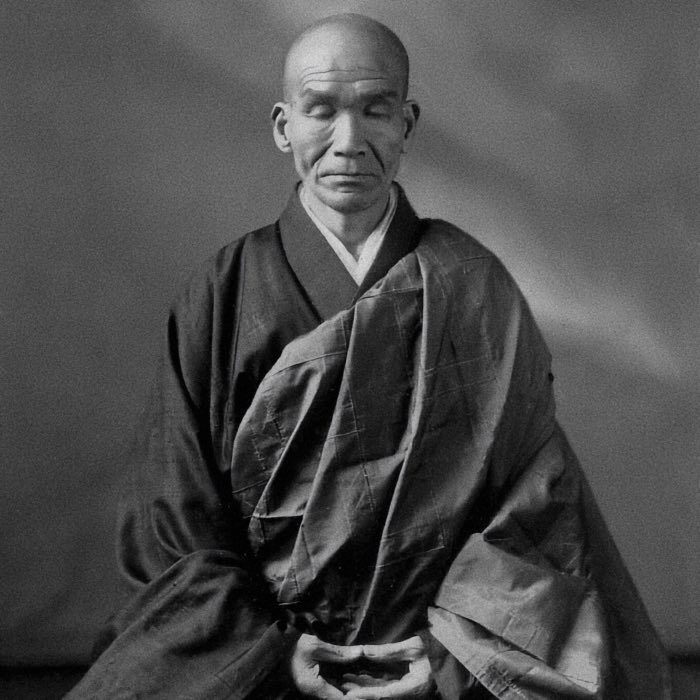

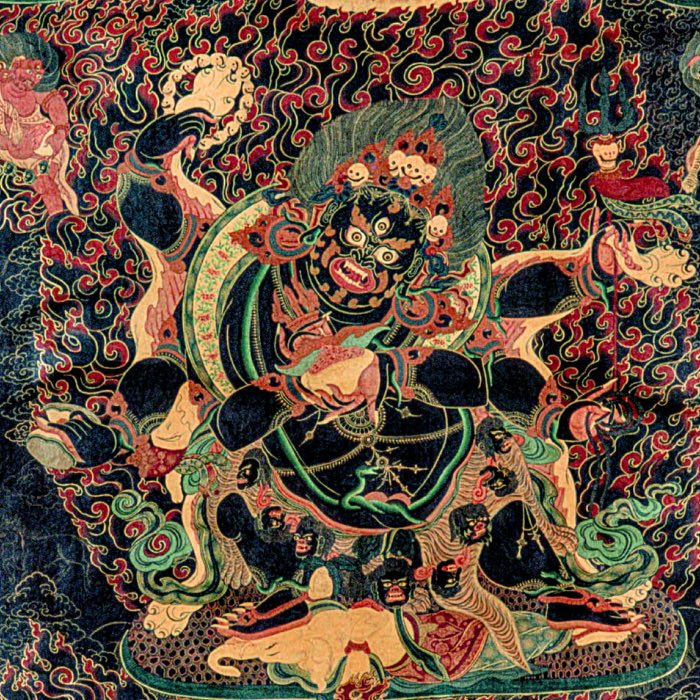

From China, it spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, where it further adapted to local traditions. Zen Buddhism, prominent in Japan, influenced various aspects of life, including art and martial disciplines. Meanwhile, in Tibet, Vajrayana Buddhism evolved, blending with indigenous Bön traditions and creating a unique form of Tantric Buddhism.

The development of Mahayana Buddhism around the 1st century CE marked a significant evolution in Buddhist thought and practice. Mahayana, which emphasized the ideal of the bodhisattva (an enlightened being who delays final liberation to help others), coexisted with the earlier Theravāda tradition, which focused on individual liberation (nirvāṇa). Mahayana Buddhism also spread to Southeast Asia, notably influencing Vietnam and Indonesia, where the Srivijaya kingdom became a center of learning. The Borobudur temple in Java exemplifies the region’s Buddhist heritage.

Monks following Pradakshina at Borobudur temple in Java, Indonesia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

From the 4th to the 7th centuries CE, under the patronage of the Gupta Empire, Buddhism reached new intellectual heights. Renowned centers of learning such as Nālandā University and Vikramashila attracted scholars from across Asia. Philosophers like Nāgārjuna, who developed the Madhyamaka school, and Dignāga, a pioneer in Buddhist logic, made significant contributions to Buddhist philosophy.

Ruins of the ancient University of Nālandā (5th–12th centuries CE) in Bihar, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ruins of the ancient University of Vikramashila (8th–12th centuries CE) in Bihar, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

However, by the 8th century CE, ](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-16-buddhism/)Buddhism](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-16-buddhism/) began to decline in India due to several factors, including the resurgence of Brahmanical traditions, the rise of devotional movements (bhakti) in Hinduism, and the increasing influence of Advaita Vedanta. The invasions by Muslim rulers in the 12th century CE led to the destruction of major Buddhist monasteries, further contributing to its decline. By the end of the medieval period, Buddhism had largely disappeared from the Indian subcontinent, surviving primarily in regions such as Tibet, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

In the modern era, Buddhism spread globally with Asian immigrant communities establishing temples in Europe, North America, and Australia. Interest in Buddhist philosophy, meditation, and mindfulness practices has grown among non-Asian populations, enhancing its global presence. Buddhism’s adaptability and engagement with diverse cultures have allowed it to thrive across different societies while maintaining its core teachings.

Today’s spread of Buddhism worldwide (percentage of Buddhists by country). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Today’s spread of Buddhism worldwide (percentage of Buddhists by country). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

In India, Buddhism experienced a revival in the mid-20th century through the efforts of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who led a mass conversion movement among Dalits. Today, Buddhism in India is represented by various schools, including Theravāda, Mahayana, and Vajrayana, and continues to attract followers seeking its message of compassion and wisdom.

Today’s distribution of Buddhism in India: District wise percentage of the Buddhist population according to the 2011 census. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Conclusion

The emergence of Buddhism in ancient India represents a transformative moment in the history of Indian philosophy. By engaging with and reinterpreting existing concepts such as karma, samsāra, ātman, and mokṣa, the Buddha offered a radical new path centered on personal experience, ethical conduct, and meditative insight. Buddhism’s distinctive teachings on anatta and nirvāṇa, along with its pragmatic approach to spiritual practice, set it apart from other contemporary schools and contributed to its widespread appeal.

Devotees performing puja at one of the Buddhist Caves in Ellora, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Buddhism’s intellectual contributions, particularly in the areas of ethics, epistemology, and logic, influenced philosophical thought in India and beyond. By challenging traditional orthodoxies and offering a practical path to liberation, Buddhism inspires seekers of wisdom and compassion around the world.

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Gethin, R., The Foundations of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192892232

- Johannes Bronkhorst, Greater Magadha: Studies in the culture of early India, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359663975

- Edward Conze, Buddhist thought in India: Three phases of Buddhist philosophy, 1967, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0472061297

- John S. Guy, Tree and serpent: Early Buddhist art in India, 2023, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 9781588396938

comments