Hinduism: A historical overview

Hinduism, one of the oldest surviving religious traditions in the world, is characterized by its vast diversity of beliefs, practices, and philosophies. Its roots can be traced back to the early Vedic period (circa 1500 BCE) and possibly even earlier to the prehistoric cultures of the Indus Valley Civilization. Unlike most world religions, Hinduism lacks a single founder, a unified creed, or a central religious authority. Instead, it evolved over millennia through the integration of diverse cultural and philosophical influences in the Indian subcontinent. In this post, we explore the historical development of Hinduism, briefly touch its core texts, and take a look at its key philosophical ideas.

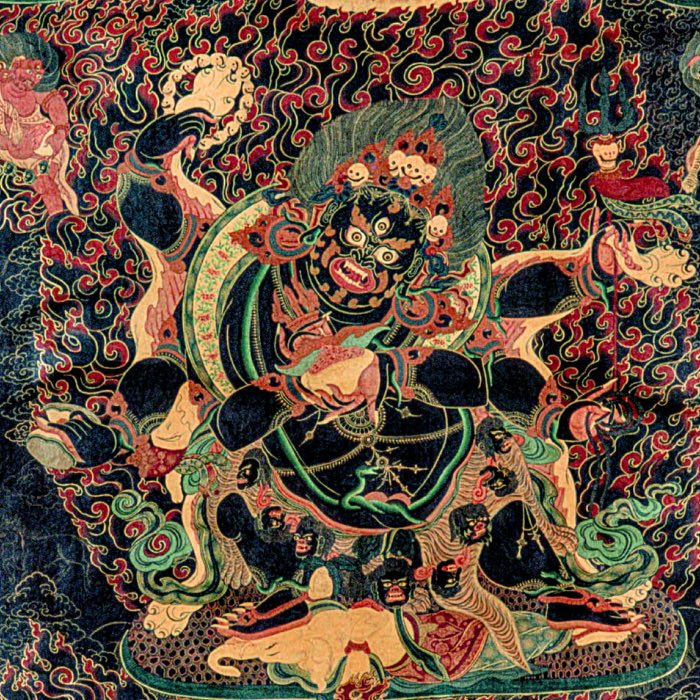

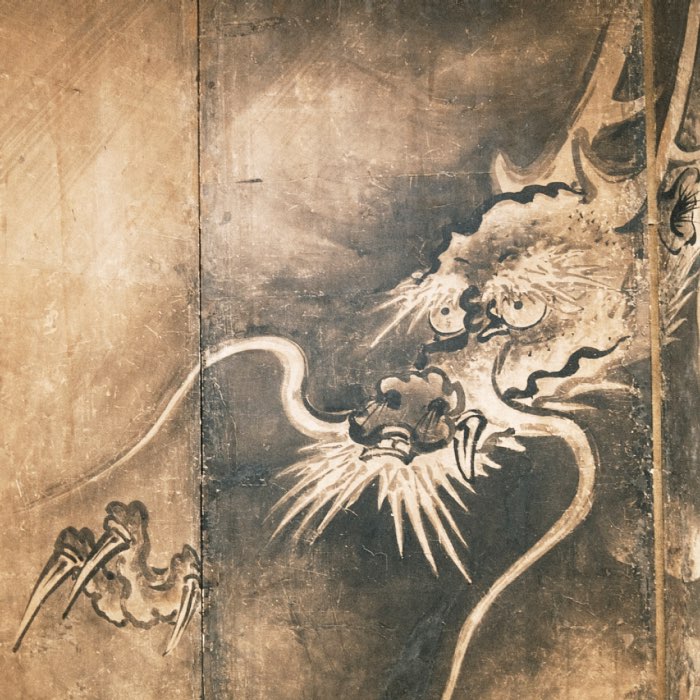

The Hindu God Vishnu, India, Tamil Nadu, 13th century, copper alloy. Vishnu (or Viṣṇu) is one of the principal deities of Hinduism, known as the preserver of the universe. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical background: From the Indus Valley to Vedic traditions

The earliest evidence of religious activity in India comes from the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500–1900 BCE). Archaeological findings, such as seals depicting figures in meditative postures, the worship of animal deities, and possible proto-Śiva icons, suggest the presence of ritualistic and spiritual practices. However, the precise connection between these practices and later Hinduism remains speculative, as the script of the Indus Valley remains undeciphered.

Srirangam Ranganathaswamy Temple, India, dedicated to the Hindu deity Vishnu, is said to be worshiped by Ikshvaku (and the descendants of Ikshvaku Vamsam). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

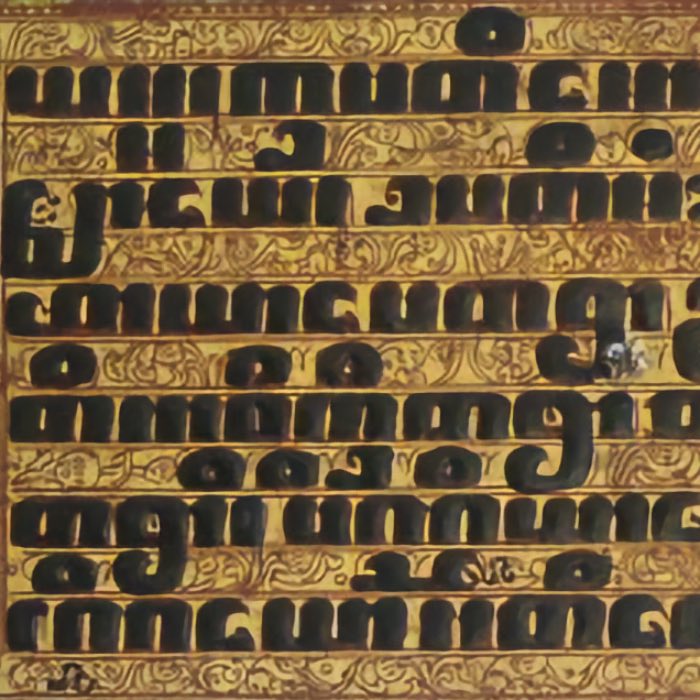

The emergence of the Vedic tradition marked a significant turning point in the development of Hinduism. The Vedas, a collection of hymns and rituals composed in Sanskrit by the Indo-Aryans around 1500–500 BCE, form the foundational texts of early Hindu thought. The four Vedas — Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda — are primarily concerned with ritual sacrifices (yajña) aimed at maintaining cosmic order (ṛta). The principal deities of this period, such as Agni (fire), Indra (storm and war), and Varuṇa (cosmic law), reflect a polytheistic worldview centered on natural forces.

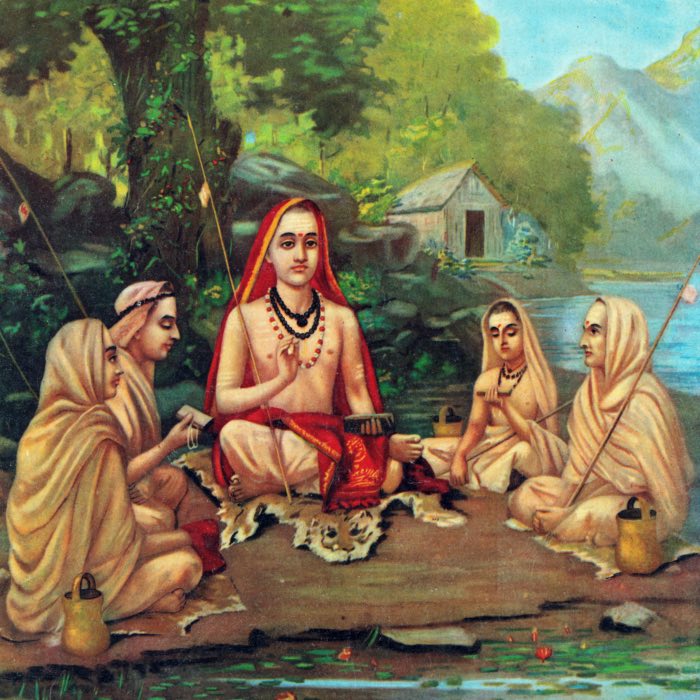

Transition from ritual to philosophy: The Upanishads

By the late Vedic period (circa 800–500 BCE), a shift occurred from ritualistic practices to philosophical inquiry. This transition is best exemplified by the Upanishads, a set of texts appended to the Vedas that focus on metaphysical questions concerning the nature of reality, the self, and ultimate liberation (mokṣa). The Upanishads introduced several key concepts that became central to Hindu philosophy:

- Brahman: The ultimate, unchanging reality that pervades the universe, often described as pure consciousness.

- Ātman: The individual self or soul, which is ultimately identical to brahman in the Advaita (non-dualist) interpretation.

- Karma: The law of cause and effect governing moral actions.

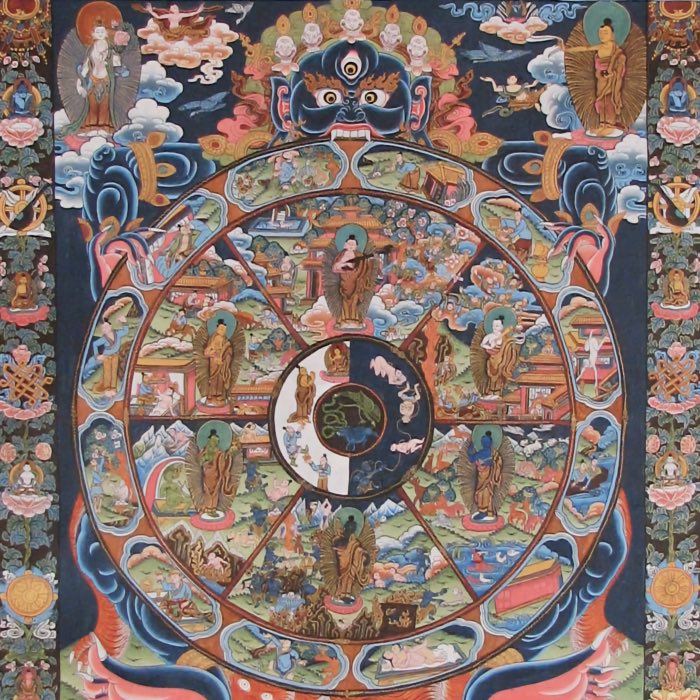

- Samsāra: The cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

- Mokṣa: Liberation from the cycle of samsāra, achieved through self-realization and the knowledge of brahman.

The Upanishadic period laid the groundwork for diverse philosophical schools of thought, collectively known as darśanas, which further elaborated on these ideas.

Philosophical schools of Hinduism

Hindu philosophy is traditionally divided into six orthodox (āstika) schools, all of which accept the authority of the Vedas:

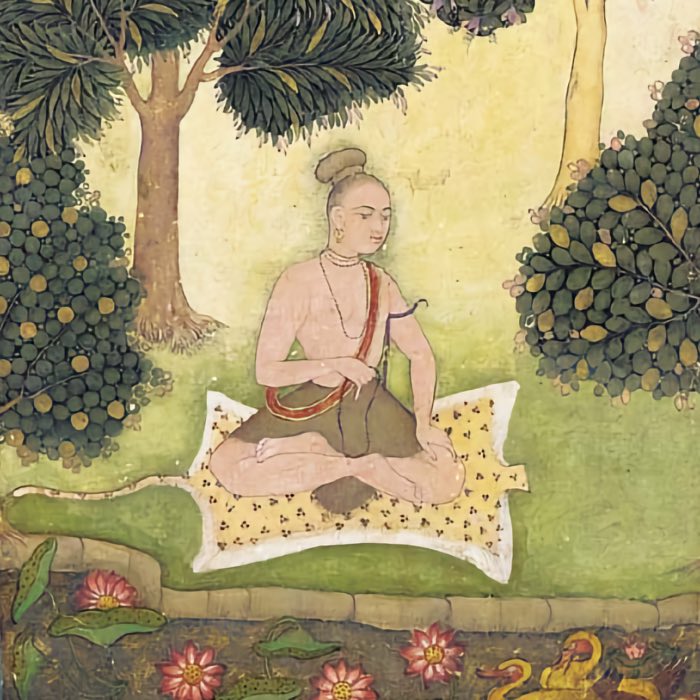

- Sāṃkhya: One of the oldest schools, Sāṃkhya posits a dualistic cosmology of puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter). Liberation is achieved by discerning the distinction between the two.

- Yoga: Closely related to Sāṃkhya, Yoga emphasizes disciplined practice (sādhana) to attain spiritual liberation. The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali outline an Eightfold Path (aṣṭāṅga yoga) for self-purification and meditation.

- Nyāya: A school of logic and epistemology, Nyāya focuses on valid means of knowledge (pramāṇa) and employs rigorous argumentation to establish philosophical truths.

- Vaiśeṣika: A school of atomism, Vaiśeṣika proposes that the universe is composed of indivisible particles (anu) and categorizes reality into six or seven fundamental substances (padārtha).

- Mīmāṃsā: Primarily concerned with the interpretation of Vedic rituals, Mīmāṃsā emphasizes the eternal nature of the Vedas and the performance of duty (dharma) as a means to sustain cosmic order.

- Vedānta: Perhaps the most influential school, Vedānta is based on the philosophical teachings of the Upanishads. It has several sub-schools, including Advaita (non-dualism), Viśiṣṭādvaita (qualified non-dualism), and Dvaita (dualism), each offering distinct interpretations of the relationship between brahman and ātman.

Hinduism in practice: Rituals, deities, and festivals

Despite the philosophical diversity, Hinduism is also characterized by its rich ritualistic and devotional practices. Worship (pūjā) can be conducted in homes or temples and often involves offerings to deities, chanting of hymns, and recitation of sacred texts. Hinduism recognizes a vast pantheon of deities, each representing different aspects of the divine:

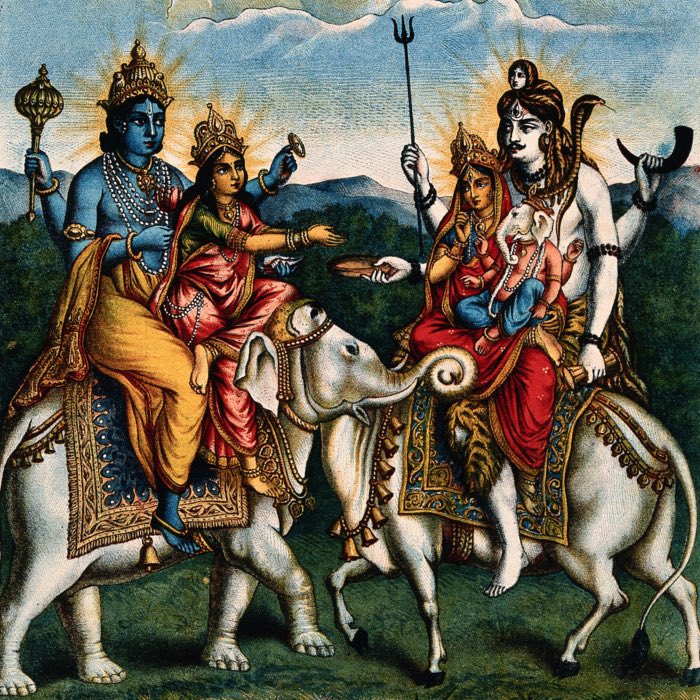

- Viṣṇu: The preserver of the universe, often worshipped through his avatars such as Rāma and Kṛṣṇa.

- Śiva: The destroyer and transformer, associated with asceticism and the cosmic dance (tāṇḍava).

- Brahmā: The creator deity, building a trinity of supreme divinity (the trimurti) together with Viṣṇu and Śiva. He is also associated with knowledge and the Vedas.

- Devī: The goddess, revered in her various forms such as Lakṣmī (prosperity), Sarasvatī (knowledge), and Durgā (power).

The trinity of supreme divinity (the trimurti), from left to right: Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: Miniature painting of Vishnu and Lakshmi, circa 1810, Salar Jung Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Center: Vishnu (Beikthano) in Burmese representation, on his mount (vehicle), the garuda (galone). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: A male sculpture believed to be Vishnu, 12th-13th century Kediri, East Java. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

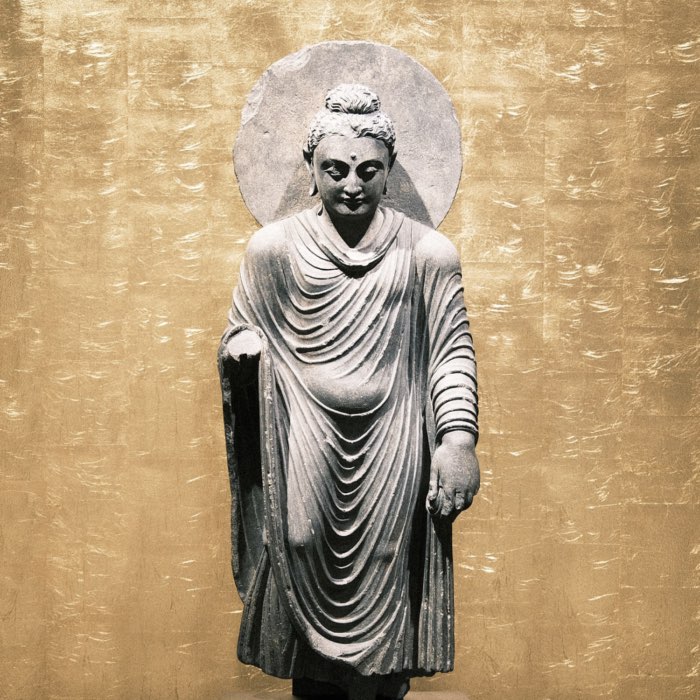

Left: Modern Shiva statue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Center Left: Chola dynasty statue depicting Shiva dancing as Nataraja. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Center Right: A seated Shiva holds an axe and deer in his hands. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Three-headed Shiva, Gandhara, 2nd century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: Painting depicting Brahma on a Hansa, c. 1700 CE, probably Nurpur, Punjab Hills, Northern India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Center: Brahma at the 12th century CE Chennakesava Temple, Somanathapura. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Brahma at a 6th century CE Aihole temple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Devis – Left: Goddess Durga, fighting Mahishasura, the buffalo-demon (from a Hindu mythology). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Center: Lakshmi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: A goddess probably Parvati as Durga riding on a lion presenting an infant Ganesha to her mother Menaka. Chromolithograph. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Major festivals such as Diwali, Holi, and Navratri celebrate different mythological events and seasonal changes, fostering a sense of community and continuity.

Kedar Ghat, a bathing place for pilgrims on the Ganges at Varanasi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

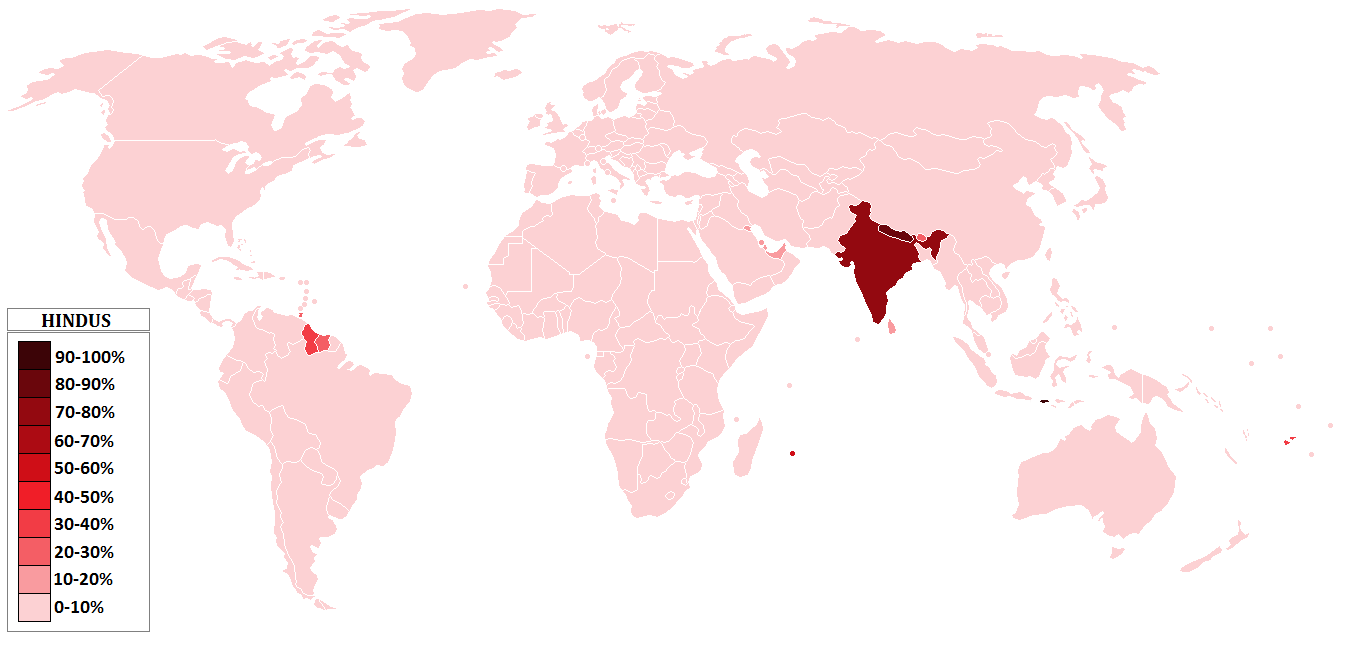

Spread of Hinduism

Hinduism, although primarily rooted in the Indian subcontinent, spread beyond its borders through ancient trade, cultural exchanges, and later, migration. The first major phase of expansion occurred between the 1st and 7th centuries CE, when Indian traders, priests, and scholars brought Hindu ideas to Southeast Asia. This led to the development of Hindu-influenced kingdoms such as Majapahit in Indonesia and the Khmer Empire in Cambodia. Temples like Angkor Wat, initially dedicated to Viṣṇu, stand as enduring legacies of Hinduism’s early influence. In Bali, Hinduism has remained dominant, preserving ancient rituals and traditions.

Spread of Hinduism worldwide. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Nepal has long been a significant center of Hinduism, historically the world’s only Hindu kingdom until becoming a secular state in 2008. Nepalese Hinduism shares much with Indian traditions while incorporating unique local practices. Important religious sites, such as the Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu, draw pilgrims from across the region. Festivals like Dashain and Tihar illustrate the syncretic blend of Hindu and indigenous elements in Nepalese culture.

Prambanan Hindu temple complex built in the 9th century, Java, Indonesia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The second phase of Hinduism’s spread occurred during the colonial era, when Indian indentured laborers were taken to the Caribbean, Africa, and Southeast Asia. This migration established Hindu communities in countries such as Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname, Mauritius, and Fiji. Despite being far from their homeland, these communities preserved their religious practices and built temples, ensuring the continuity of their cultural heritage.

Pashupatinath Temple in Nepal, dedicated to the Hindu deity Shiva as the lord of all beings. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

In the 20th and 21st centuries, a wave of Indian professionals and students migrated to Europe, North America, and Australia, forming vibrant Hindu communities in cities like London, New York, and Toronto. Hindu temples in these countries serve as both religious and cultural centers, hosting festivals and promoting traditional arts. Prominent temples such as the Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in London exemplify Hinduism’s growing influence in the West.

Puja at Pura Besakih, one of the most significant Balinese Hinduism temples. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Beyond physical communities, Hindu philosophy has spread globally, particularly through the popularization of Yoga and meditation. Figures such as Swami Vivekananda and Paramahansa Yogananda introduced Vedantic ideas to the West, while movements like Transcendental Meditation and ISKCON (The International Society for Krishna Consciousness) further disseminated Hindu teachings. Today, Hinduism’s global presence is marked not only by its religious practices but also by its influence on modern wellness, spirituality, and culture.

Conclusion

Hinduism, one of the oldest continuous religious traditions, reflects a dynamic synthesis of ritual, philosophy, and cultural adaptation. Emerging from the Vedic period and evolving through the philosophical insights of the Upanishads, Hinduism integrated diverse regional beliefs and practices over millennia. Its pluralistic nature, characterized by various schools of thought and devotional traditions, allowed it to endure and expand, influencing regions such as Southeast Asia and adapting to global contexts through modern diaspora communities. This adaptability, combined with intellectual depth and cultural richness, has ensured Hinduism’s persistence as a major religious and philosophical tradition practiced by over a billion people today.

Om, a stylised letter of the Devanagari script, used as a religious symbol in Hinduism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

References and further reading

- Flood, An introduction to Hinduism, 1996, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521438780

- Klostermaier, A survey of Hinduism, 2007, SUNY Press, ISBN: 978-0791470824

- Olivelle, The early Upanishads: Annotated text and translation, 1999, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195124354

- Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- Wendy Doniger, The Hindus: An alternative history, 2010, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0143116691

- Jamison, S. W., & Brereton, J. P., The Rigveda: the earliest religious poetry of India, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199370184

- Gonda, J., Vedic ritual: the non-solemn rites, 1997, Brill, ISBN: 978-9004062108

- Olivelle, P., The early Upanishads: annotated text and translation, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195124354

- Doniger, W., The Rig Veda: An Anthology of One Hundred and Eight Hymns, 1981, Penguin Classics, ISBN: 978-0140444025

comments