Daoism: The Chinese philosophy of the Way

Daoism, one of the principal philosophical and religious traditions of China, has profoundly influenced the development of Chinese civilization for over two millennia. Rooted in the pursuit of harmony with the Dao (Tao), or “the Way”, Daoism presents a worldview that emphasizes simplicity, spontaneity, and alignment with the natural order. From its earliest philosophical expressions in the Dao De Jing and Zhuangzi to its later evolution into a religious tradition with rituals and alchemical practices, Daoism has been instrumental in shaping Chinese thought, aesthetics, governance, and medicine.

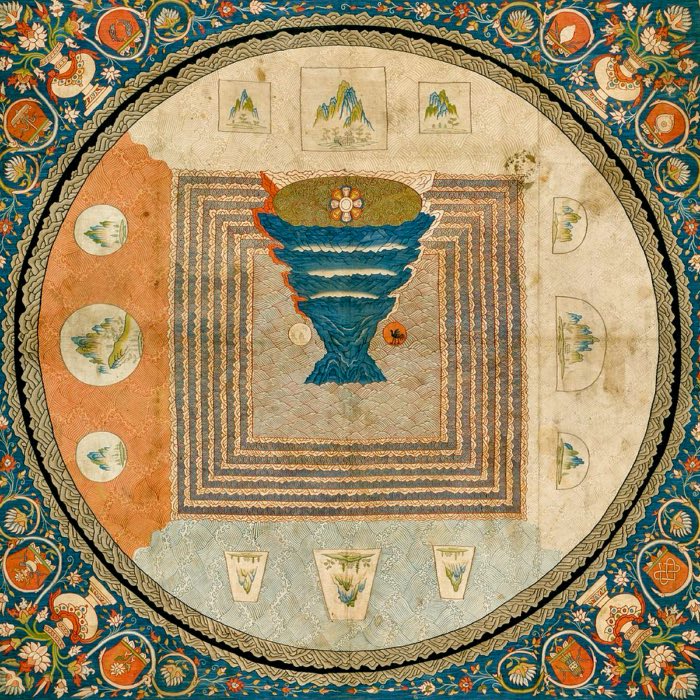

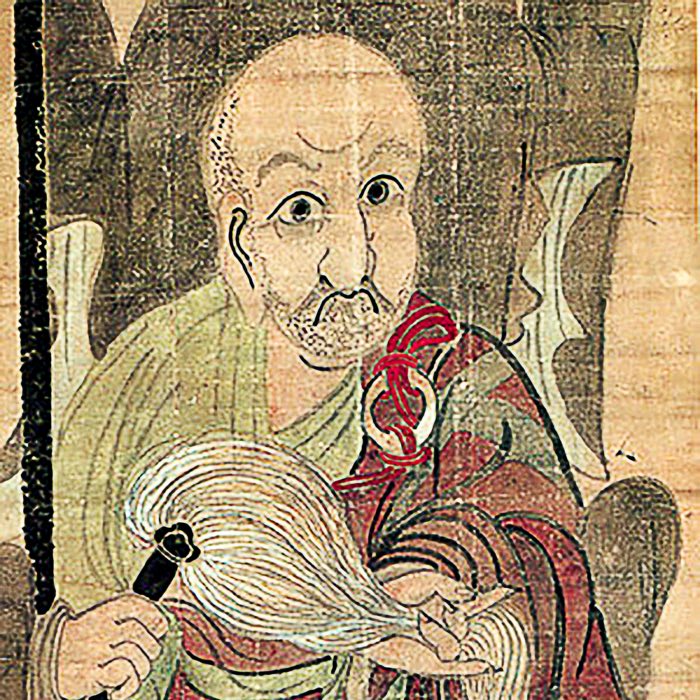

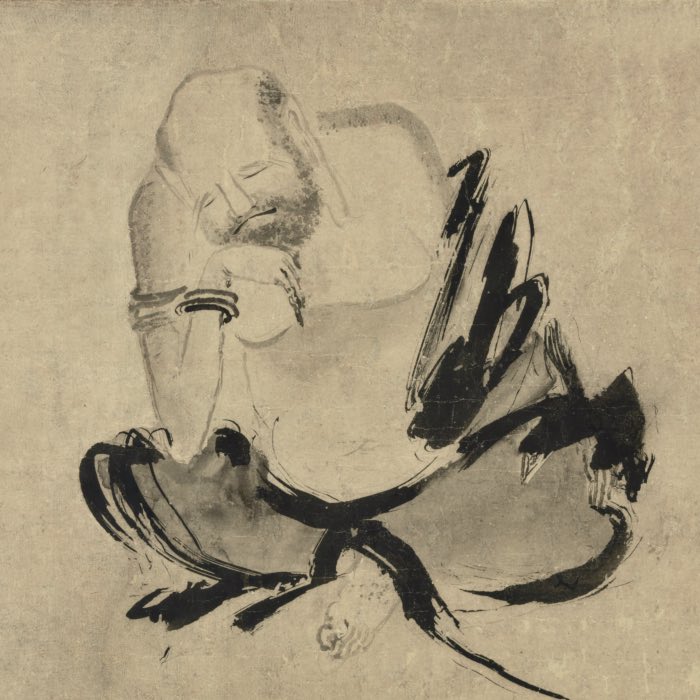

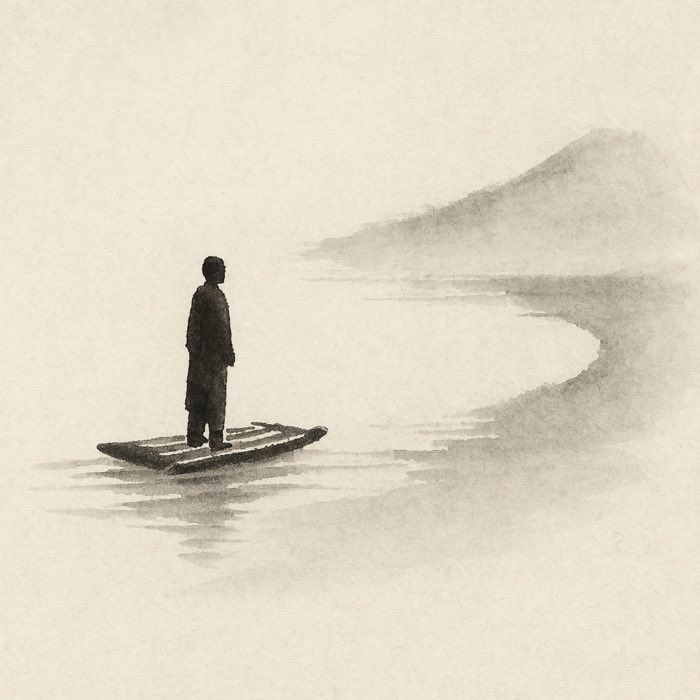

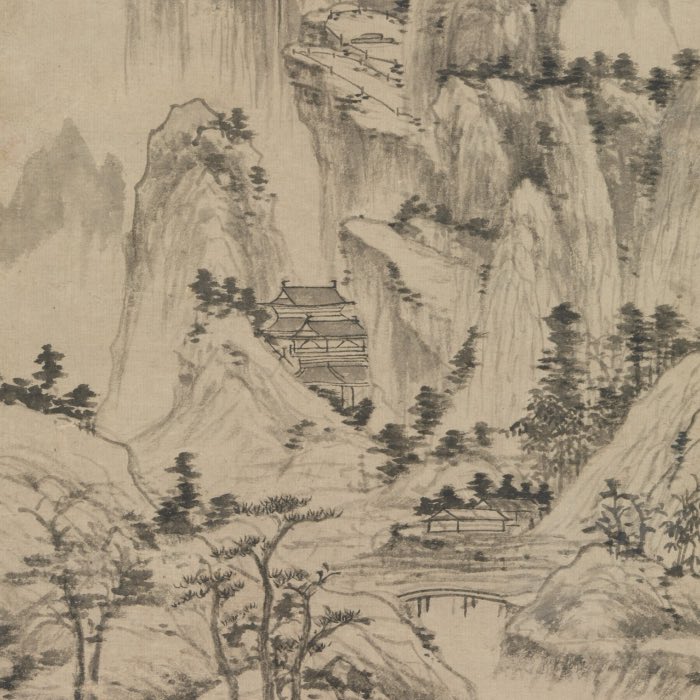

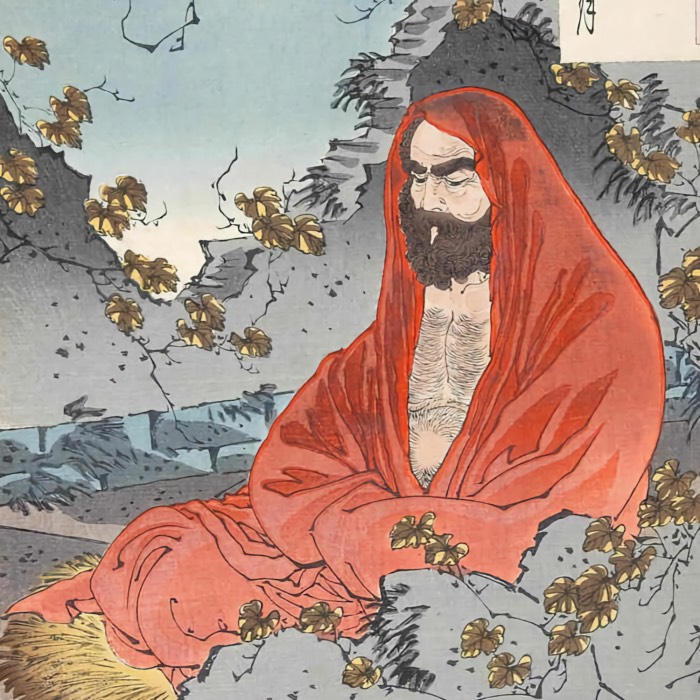

Daoist immortal Lü Dongbin Crossing Lake Dongting, Southern Song, mi-13th century, handscroll, Ink and color on silk. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Unlike other philosophical systems that focus on rigid social structures or abstract metaphysical speculation, Daoism offers a holistic approach to life, blending philosophical inquiry with practical wisdom. Its ideals of wu wei (effortless action) and ziran (naturalness) have inspired Chinese art and literature, emphasizing harmony with nature and the cosmos. Moreover, Daoist principles have left an enduring mark on Chinese political theory, advocating minimal interference and governance through virtue.

Philosophical origins of Daoism

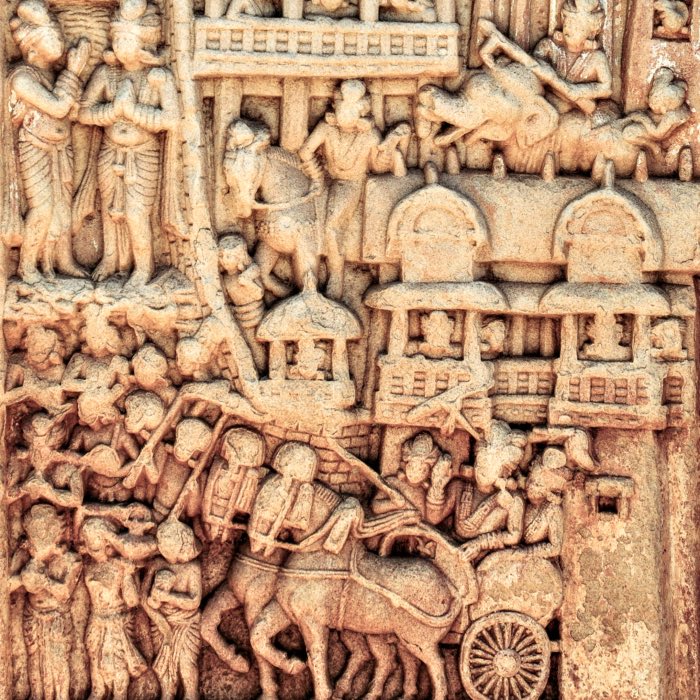

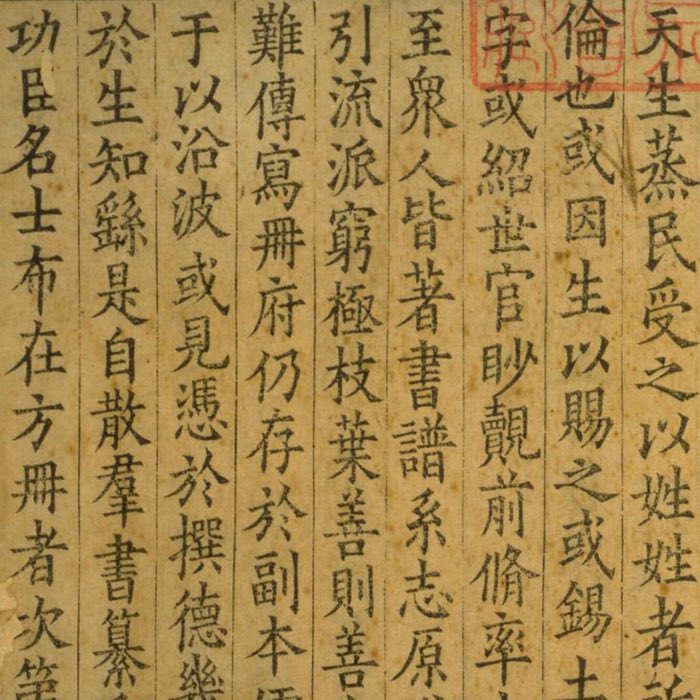

The foundational texts of Daoism, the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching) and the Zhuangzi, reflect the earliest philosophical aspects of this tradition. Traditionally attributed to Laozi (Lao Tzu), the Dao De Jing, written around the 4th to 3rd century BCE, serves as a concise yet profound guide on how to live in accordance with the Dao. Laozi’s teachings stress simplicity, humility, and non-action (wu wei), a principle that encourages flowing with the natural order rather than attempting to control it.

The birthplaces of notable Chinese philosophers from the Hundred Schools of Thought in the Zhou dynasty. Philosophers of Daoism are marked by triangles in dark green. Confucians are marked by triangles in dark red. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Zhuang Zhou (Zhuangzi), a contemporary or successor of Laozi, expanded on these ideas in his eponymous text, the Zhuangzi. While the Dao De Jing presents the Dao as a cosmic principle, the Zhuangzi adopts a more skeptical and relativistic tone, questioning human conventions and proposing a liberated existence beyond societal norms. The Zhuangzi emphasizes spontaneity and the relativity of perspectives, highlighting the futility of rigid distinctions between good and bad, life and death, and self and other.

A temple in the Wudangshan, a sacred space in Daoism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Core concepts in Daoist philosophy

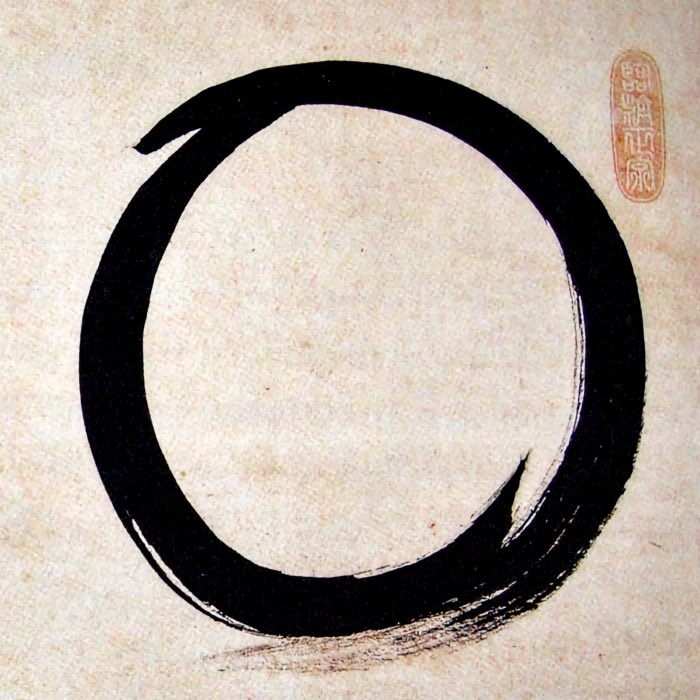

The Chinese character 道, Dao. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Dao

At the heart of Daoist philosophy lies the concept of the Dao. Unlike a deity or a fixed entity, the Dao is an ineffable and ever-present force underlying all of existence. The Dao is not something that can be fully comprehended through rational thought; instead, it must be experienced and aligned with. According to the Dao De Jing, “The Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao.” This opening line underscores the ineffability of the Dao and the limitations of language in capturing ultimate reality.

Wu wei

Wu wei, often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action”, is a central tenet of Daoism. It does not imply complete passivity but rather acting in harmony with the natural flow of events. The Daoist sage engages in action that is spontaneous, unobstructed, and in accord with the Dao, avoiding forceful or contrived efforts that disrupt the natural balance.

Ziran

The concept of ziran (spontaneity or naturalness) complements wu wei. It represents the state of being that arises when one follows the Dao without artificial interference. A person living according to ziran acts in a manner that is authentic and in tune with their nature, embodying simplicity and openness.

Yin and Yang

Although Daoism did not originate the concept of yin and yang, it incorporates this dualistic principle to describe the dynamic balance of opposites in the universe. Yin represents the receptive, dark, and feminine, while yang symbolizes the active, light, and masculine. The interplay of yin and yang creates harmony in the cosmos, and understanding this balance is essential for living in accordance with the Dao.

Other key concepts

- De

- Virtue or integrity, which arises from living in harmony with the Dao and cultivating inner qualities such as compassion, humility, and wisdom.

- Fenfliu

- The concept of transformation or change, reflecting the Daoist understanding of the impermanence of all things and the cyclical nature of existence.

- Pu

- Simplicity or uncarved block, symbolizing the natural state of being before it is shaped by external influences. The ideal of pu emphasizes returning to one’s original nature and embracing simplicity over complexity.

- Qi

- Vital energy or life force that flows through all living beings and the cosmos.

- Xu

- Emptiness or void, representing the receptive and open state of mind that allows for the flow of the Dao. Embracing xu involves letting go of attachments and preconceptions to allow for new possibilities to emerge.

- Wuji

- The state of undifferentiated unity or non-duality, representing the primordial state of the cosmos before the emergence of yin and yang.

- Wuxing

- The Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) that symbolize the cyclical processes of transformation and interdependence in nature.

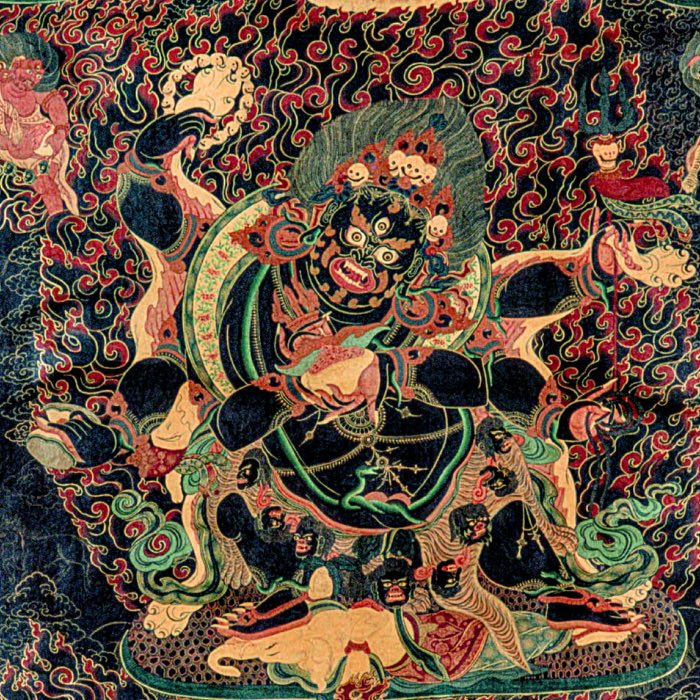

Religious Daoism

By the late Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Daoism began to evolve beyond a philosophical tradition into an organized religion. Religious Daoism incorporated rituals, alchemical practices, and beliefs in immortality. Various sects emerged, such as the Celestial Masters (Tianshi) movement and the Shangqing (Highest Clarity) tradition, each with its own rituals, texts, and deities.

Daoist ceremony at Xiao Ancestral Temple in Chaoyang, Shantou, Guangdong. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

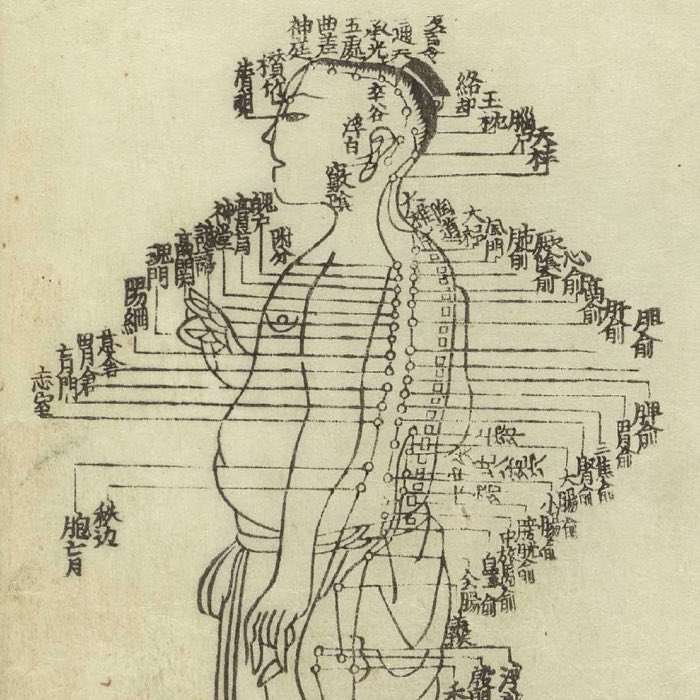

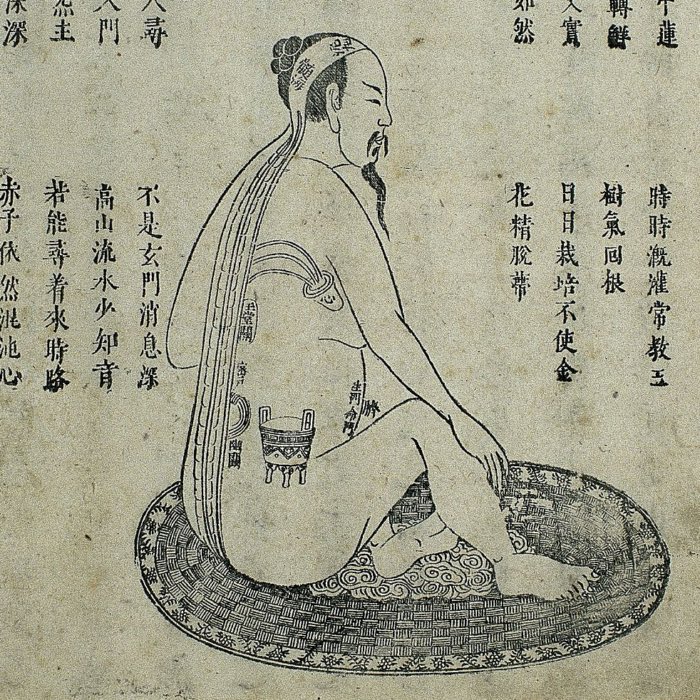

Religious Daoism introduced the concept of achieving immortality through internal and external alchemy. Internal alchemy (neidan) involved meditation, breathing exercises, and dietary practices aimed at refining the body’s vital energies (qi). External alchemy (waidan) focused on the creation of elixirs that were believed to grant immortality. These practices reflect a Daoist desire to transcend the limitations of ordinary existence and align more fully with the Dao.

Daoism and Chinese society

Daoism’s influence on Chinese society extends beyond religion and philosophy to areas such as governance, medicine, and the arts. Daoist principles have historically shaped approaches to leadership, emphasizing the importance of minimal intervention and governing through virtue rather than force. In Chinese medicine, Daoist ideas about the flow of qi and the balance of yin and yang have contributed to theories of health and healing.

Wong Tai Sin Temple, one of the most important Daoist temples in Hong Kong. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The arts, particularly poetry and landscape painting, have also been deeply influenced by Daoist aesthetics. The emphasis on natural beauty, spontaneity, and harmony with the environment is evident in classical Chinese art, where the Daoist ideal of merging with nature is a recurring theme.

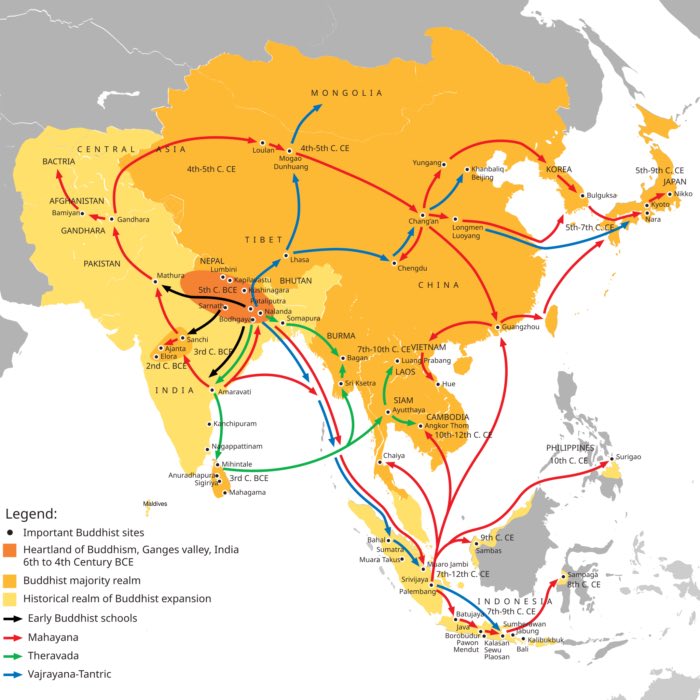

Influence of Daoism on East Asian cultures

While Daoism originated in China, its philosophical and religious ideas extended beyond its borders, influencing the cultures of neighboring East Asian countries, particularly Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. The spread of Daoism in these regions occurred primarily through cultural exchange, trade, and the dissemination of Chinese texts and practices.

Korea

In Korea, Daoist ideas were integrated into indigenous religious practices and beliefs. During the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE – 668 CE), Daoism entered Korea alongside Buddhism and Confucianism. While it never developed into a fully independent religious tradition, Daoist principles influenced Korean shamanism, art, and literature. The emphasis on harmony with nature and the quest for longevity resonated with local traditions, leading to a blending of Daoist and native beliefs.

The Daoist concept of yin and yang and the Five Elements (wuxing) became integral to Korean cosmology, medicine, and geomancy (pungsu-jiri, the Korean form of feng shui). Korean royal courts often patronized Daoist rituals aimed at ensuring the welfare of the state and the longevity of the ruler. The influence of Daoism is also evident in Korean landscape painting, which reflects a deep appreciation for natural beauty and harmony.

Japan

In Japan, Daoist ideas were introduced during the Asuka and Nara periods (6th–8th centuries CE) through Chinese cultural influence. Daoist practices and beliefs were integrated with indigenous Shinto traditions and later influenced the development of esoteric Buddhist schools, such as Shingon and Tendai.

One of the most significant Daoist influences on Japanese culture is the concept of yin and yang, which became central to Onmyōdō, a traditional Japanese cosmology and divination system. Onmyōdō practitioners, known as onmyōji, played important roles in court rituals, advising on matters related to astrology, divination, and geomancy.

Daoist-inspired aesthetics also contributed to the development of Japanese art and literature. The Daoist ideals of simplicity and naturalness can be seen in traditional Japanese gardens, tea ceremonies, and poetry, particularly in the waka and haiku forms, which emphasize a deep connection with nature. And the Daoist concept of ziran (naturalness) may have influenced the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, which celebrates imperfection, transience, and the beauty of the imperfect.

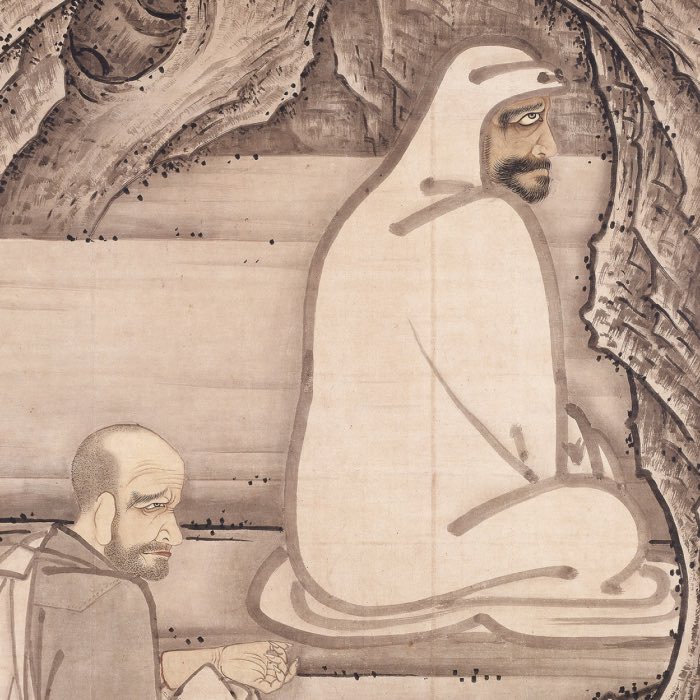

We should also not underestimate the influence of the understanding of the Dao on the development of the Japanese Zen Buddhism. The concept of the Dao and the practice of Zen Buddhism share many similarities, such as the emphasis on meditation, mindfulness, and direct experience of reality. The Daoist emphasis on spontaneity and naturalness resonated with the Zen ideal of non-duality and the direct transmission of wisdom beyond words and concepts.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, Daoism was introduced during the Chinese occupation (111 BCE – 939 CE) and became one of the key religious traditions alongside Buddhism and Confucianism. Vietnamese Daoism developed distinct characteristics, blending with local animist beliefs and practices. Daoist temples and shrines, known as đền, were established throughout the country, where rituals for health, longevity, and protection from evil spirits were performed.

The influence of Daoist thought is evident in Vietnamese folk religion, particularly in the worship of natural spirits and ancestors. The practice of pháp (ritual magic) in Vietnamese Daoism incorporates elements of Chinese Daoist alchemy and cosmology, emphasizing harmony with the natural world and the cultivation of inner power.

Daoist-inspired literature and poetry flourished in Vietnam, reflecting themes of harmony with nature, impermanence, and the quest for spiritual transcendence. Vietnamese traditional medicine also draws heavily on Daoist concepts of qi and balance, similar to Chinese medicine.

Cultural synthesis in East Asia

The spread of Daoism in East Asia contributed to a shared cultural heritage that transcended national boundaries. While Daoism did not become a dominant religious tradition outside China, its philosophical and aesthetic principles deeply influenced local cultures and religious practices. The integration of Daoist ideas with indigenous beliefs and other imported traditions, such as Buddhism and Confucianism, created unique cultural syntheses in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

Daoism in modern times

Today, Daoism remains a living tradition in China and abroad. It has undergone significant transformations throughout history, adapting to various cultural and historical contexts. In the modern era, Daoism continues to inspire philosophical inquiry, spiritual practice, and environmental ethics. The Daoist emphasis on living in harmony with nature has gained renewed relevance in discussions about sustainability and ecological balance.

While religious Daoism has declined in influence relative to its historical peak, philosophical Daoism has found new audiences worldwide. Its teachings on simplicity, mindfulness, and non-attachment resonate with contemporary seekers looking for alternative ways of understanding life and the self.

Conclusion

Daoism has profoundly shaped Chinese civilization, offering a philosophical and spiritual framework that has influenced key aspects of life in China, including governance, medicine, art, and literature. Its principles of living in harmony with the Dao, embracing simplicity, and valuing spontaneity provided a counterbalance to the structured ethics of Confucianism and the legalistic rigor of Legalism. As one of the foundational pillars of Chinese thought, Daoism’s emphasis on balance, naturalness, and inner cultivation became deeply embedded in the Chinese cultural identity.

Beyond China, Daoism left a lasting mark on East Asian cultures, particularly in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, where its philosophical and aesthetic ideals merged with indigenous traditions and Buddhism. In these regions, Daoism influenced fields such as art, literature, medicine, and even state rituals. Concepts like yin and yang, the Five Elements, and geomancy were widely adopted, contributing to a shared cultural heritage across East Asia.

Today, Daoism continues to inspire philosophical inquiry, spiritual practices, and modern environmental thought. Its legacy, both within China and throughout East Asia, underscores its enduring relevance as a system of thought that seeks harmony between humans and the natural world. By shaping both individual lives and broader cultural practices, Daoism remains a vital intellectual tradition in East Asia.

References

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

- Augustin, Birgitta, “Daoism and Daoist Art””, 2000, In: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, linkꜛ

comments