The Dao and its influence on East Asian thought

The concept of the Dao, often translated as “the Way”, is a core concept of Daoism and has significantly shaped the cultural, intellectual, and spiritual landscapes of China and East Asia. Emerging from the early philosophical traditions of ancient China, the Dao embodies a principle of universal order, spontaneity, and harmony that transcends rigid categorizations. Over centuries, the Dao became integrated not only into Daoist philosophy and religious practices but also into Confucianism, Chinese Buddhism, and later, Japanese Zen Buddhism and Shinto thought. In this post, we briefly investigate the philosophical underpinnings of the Dao and its influence on Chinese and East Asian religions.

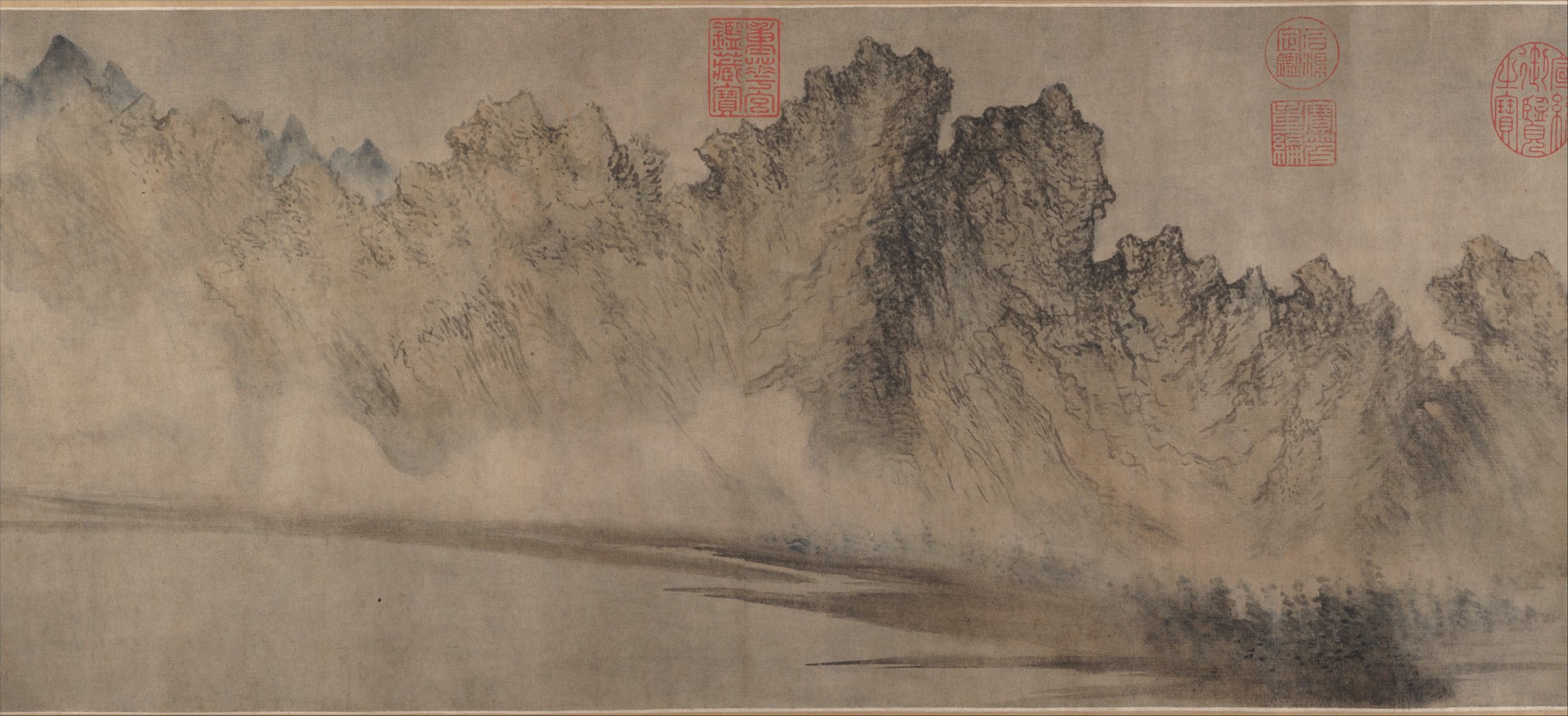

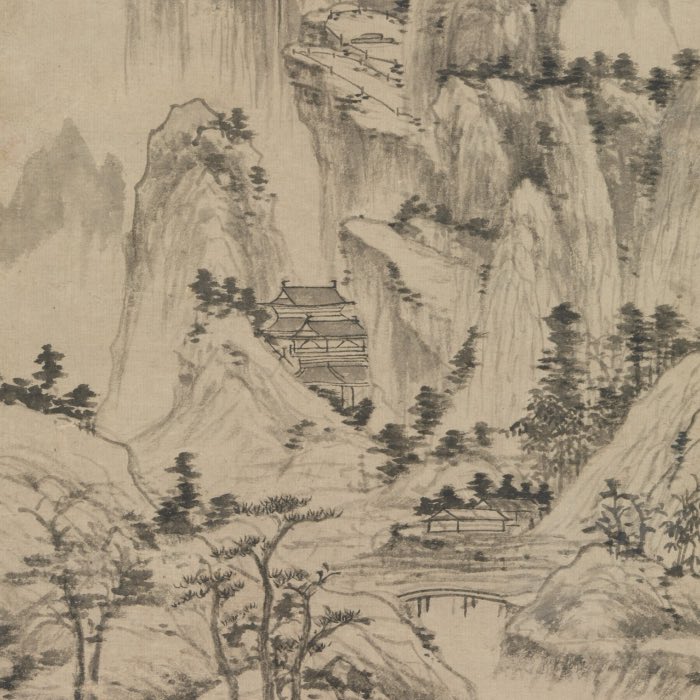

Cloudy Mountains, Fang Congyi, ca. 1360–70, handscroll, ink and color on paper, China. Fang Congyi, a Daoist priest from Jiangxi, traveled extensively in the north before settling down at the seat of the Orthodox Unity Daoist church, the Shangqing Temple on Mount Longhu (Dragon Tiger Mountain), Jiangxi province. Imbued with Daoist mysticism, he painted landscapes that “turned the shapeless into shapes and returned things that have shapes to the shapeless”. According to Daoist geomantic beliefs, a powerful life energy pulsates through mountain ranges and watercourses in patterns known as longmo (dragon veins). In Cloudy Mountains, the painter’s kinetic brushwork, wound up as if in a whirlwind, charges the mountains with an expressive liveliness that defies their physical structure. The great mountain range, weightless and dematerialized, resembles a dragon ascending into the clouds. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Arꜛ (public domain)

The Dao in early Chinese philosophy

The Dao as a philosophical concept first gained prominence through the foundational Daoist texts: the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching) and the Zhuangzi. Both works present the Dao as an underlying principle that governs the cosmos and human life, yet they offer distinct perspectives.

In the Dao De Jing, attributed to Laozi, the Dao is described as the origin of all things, a force that transcends human understanding and language. Laozi emphasizes living in harmony with the Dao through wu wei, or effortless action, which involves aligning oneself with the natural flow of life rather than opposing it. This idea stands in contrast to the Confucian emphasis on moral cultivation and social order. The Dao De Jing presents a vision of life that values simplicity, humility, and a deep respect for the natural world.

The Zhuangzi, attributed to Zhuang Zhou, expands on the metaphysical and ethical implications of the Dao. It introduces a more playful and paradoxical tone, suggesting that rigid distinctions and dogmas hinder true understanding. Zhuangzi’s writings encourage a perspective that transcends conventional judgments, emphasizing spontaneity and freedom. His philosophy reflects a relativistic view of reality, where all distinctions are fluid and contextual, a perspective that profoundly influenced later Chinese and East Asian thought.

Philosophical meaning of the Dao

At its core, the Dao represents the fundamental order underlying all existence. It is both the source and the process through which the cosmos unfolds. Unlike Western metaphysical systems that often focus on discrete entities or a creator such as the logos, Demiurge, or God, the Dao is an impersonal principle that operates without intentionality or purpose. It is described in the Dao De Jing as “the nameless origin of heaven and earth” and “the mother of all things”. The Dao is not a thing but the ever-present flow of reality, encompassing both being and non-being.

The Dao is often likened to water — yielding, flexible, and yet capable of shaping the hardest substances over time. This metaphor illustrates the Dao’s paradoxical nature: It is weak and passive, yet it holds immense power by virtue of its adaptability. This notion challenges dualistic thinking and invites a worldview in which opposites are seen as complementary rather than contradictory.

Epistemological implications of the Dao

Philosophically, the Dao raises important questions about the nature of knowledge and understanding. According to Daoist thinkers, conventional knowledge, which relies on distinctions and categories, is inherently limited. The Dao cannot be fully apprehended through rational thought or discursive reasoning. As Laozi states in the opening lines of the Dao De Jing, “The Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao”.

This skepticism toward conventional knowledge reflects a broader Daoist epistemology that values direct, intuitive understanding over intellectual analysis. Zhuangzi, in particular, critiques reliance on rigid concepts and fixed perspectives, advocating for a form of knowledge that is fluid and responsive to changing circumstances. True wisdom, in this view, involves attuning oneself to the Dao and embracing the ever-changing nature of reality without clinging to fixed notions or rigid identities.

Ethical dimensions of the Dao

The ethical implications of the Dao are rooted in the principle of wu wei, often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action.” In the Daoist context, wu wei does not imply inaction in the sense of passivity or laziness. Instead, it refers to a mode of action that is spontaneous, unforced, and in harmony with the natural flow of events. Ethical behavior, according to Daoism, arises not from adherence to external rules or moral codes but from an alignment with the Dao.

By acting in accordance with the Dao, individuals can cultivate ziran, or naturalness. This state of being involves living authentically and without artificial imposition, allowing one’s actions to flow naturally from their intrinsic nature. The ethical life in Daoism is thus one of simplicity, humility, and attunement to the world’s inherent rhythms. This contrasts sharply with the Confucian emphasis on deliberate moral cultivation and societal roles.

Moreover, Daoism’s ethical framework extends beyond human relations to encompass the entire natural world. The Daoist reverence for nature, reflected in its metaphors and imagery, underscores an ecological ethic that values harmony with the environment. This ecological perspective, though articulated in ancient terms, resonates with contemporary concerns about sustainability and environmental stewardship.

Paradox and the dialectics of the Dao

A key feature of Daoist philosophy is its use of paradox to convey the nature of the Dao. The Dao De Jing is replete with statements that appear contradictory, such as “The soft overcomes the hard” and “The wise person knows they do not know”. These paradoxes serve to undermine conventional thinking and point toward a deeper, non-dual understanding of reality.

Daoism rejects rigid dualisms — such as good and evil, life and death, or self and other — in favor of a dialectical view in which opposites are seen as interdependent and constantly transforming into one another. This dialectical approach reflects the Dao’s dynamic nature: it is not a fixed essence but a process of perpetual change and transformation.

Dao as a model for existence

Ultimately, the philosophical meaning of the Dao is best understood not as a static concept but as a model for living and being. To live according to the Dao is to embrace life’s uncertainty, complexity, and impermanence with openness and equanimity. It involves cultivating a state of presence, spontaneity, and harmony with the world as it is, rather than imposing one’s will upon it.

Philosophically, the Dao challenges human hubris — the belief that we can fully control or comprehend the world. It invites a stance of humility, wonder, and receptivity, encouraging individuals to find their place within the broader unfolding of the cosmos. In this sense, the Dao is both a metaphysical principle and an ethical ideal, offering a way of life that is inextricably linked to the natural order.

Influence of the Dao on Confucianism and Chinese statecraft

Despite their apparent differences, Daoism and Confucianism shared a long history of mutual influence. During the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), the Dao became integrated into Confucian philosophy, particularly through the work of Dong Zhongshu, who synthesized Confucian ethics with cosmological ideas derived from Daoism and Yin-Yang theory. This synthesis led to the development of a Confucian worldview in which the Dao represented the moral order of the universe.

In Confucian statecraft, the ruler was expected to embody the Dao through virtuous governance, ensuring harmony between heaven, earth, and humanity. While Confucianism emphasized social order and ethical duties, Daoist ideas of non-coercive leadership and harmony with natural rhythms influenced the ideal of the “sage-king”, a ruler who governs with minimal intervention, allowing society to flourish organically. This ideal of non-coercive governance found practical application in various Chinese dynasties, where periods of Daoist influence led to policies that favored simplicity, agrarian life, and reduced taxation.

Daoism and Chinese Buddhism

The encounter between Indian Buddhism and indigenous Chinese thought led to the emergence of a distinctly Chinese form of Buddhism, heavily influenced by Daoism. Early Chinese translators of Buddhist texts used Daoist terminology to render key Buddhist concepts, resulting in a fusion of ideas. For example, the Buddhist notion of nirvana was often equated with the Dao, and the principle of wu wei was associated with the Buddhist concept of non-attachment.

The Chán (Zen) school of Buddhism, which later spread to Japan, was particularly shaped by Daoist ideas. Chán emphasized direct experience, spontaneity, and the ineffability of ultimate truth — concepts reminiscent of the Daoist critique of language and rational thought. The Chán practice of meditation (zuo chan) can be seen as an embodiment of wu wei, where the practitioner seeks to harmonize with the natural flow of existence without striving or forcing.

Transmission of Daoist thought to Japan

Daoist philosophy reached Japan primarily through the transmission of Chinese culture and Buddhism. Although Daoism did not develop as a distinct religious institution in Japan, its influence permeated Japanese thought and practice, particularly through the Zen Buddhist tradition and Shinto, Japan’s indigenous spiritual system.

Zen Buddhism, which flourished in Japan from the 12th century onward, bears many hallmarks of Daoist influence. The Zen emphasis on direct, intuitive insight and the rejection of dualistic thinking mirrors the teachings of Zhuangzi. Zen art, including calligraphy, garden design, and tea ceremony, reflects the Daoist aesthetic of simplicity, naturalness (ziran), and spontaneity. The Zen ideal of living in harmony with nature resonates deeply with the Daoist worldview.

In Shinto, the reverence for natural phenomena and the belief in the spiritual essence of the natural world echo Daoist ideas about the interconnectedness of all things. Although Shinto developed independently of Daoism, its later syncretism with Buddhism and the influence of Daoist-inspired Zen contributed to a shared East Asian cultural emphasis on harmony with nature and the flow of life.

The Dao in East Asian aesthetics

The Daoist influence on East Asian aesthetics is evident in various art forms, including landscape painting, poetry, and garden design. Chinese landscape painting, especially during the Tang and Song dynasties, often depicted vast, serene natural scenes intended to evoke the Dao. The paintings conveyed a sense of boundless space and spontaneity, inviting viewers to contemplate their place within the cosmos.

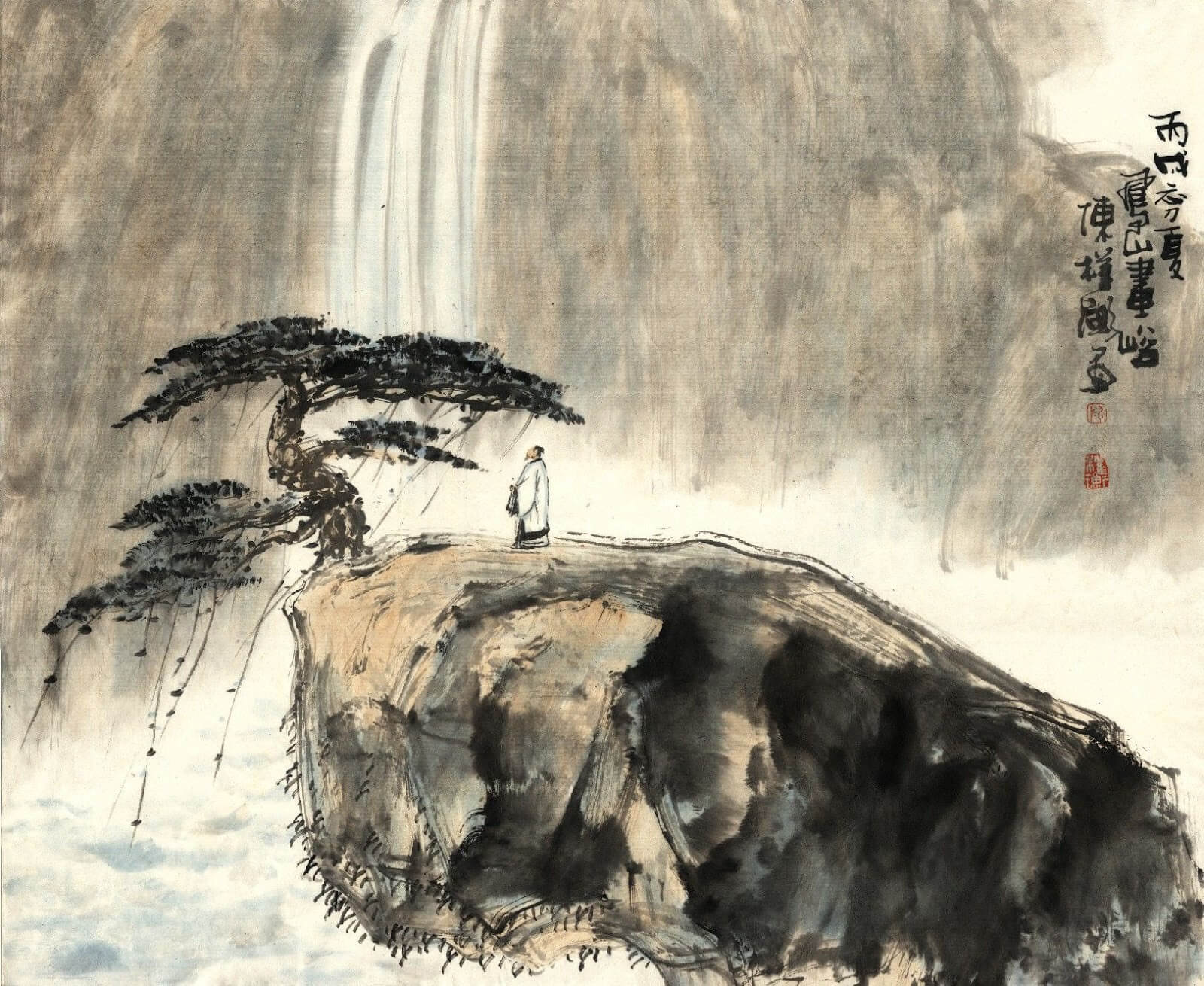

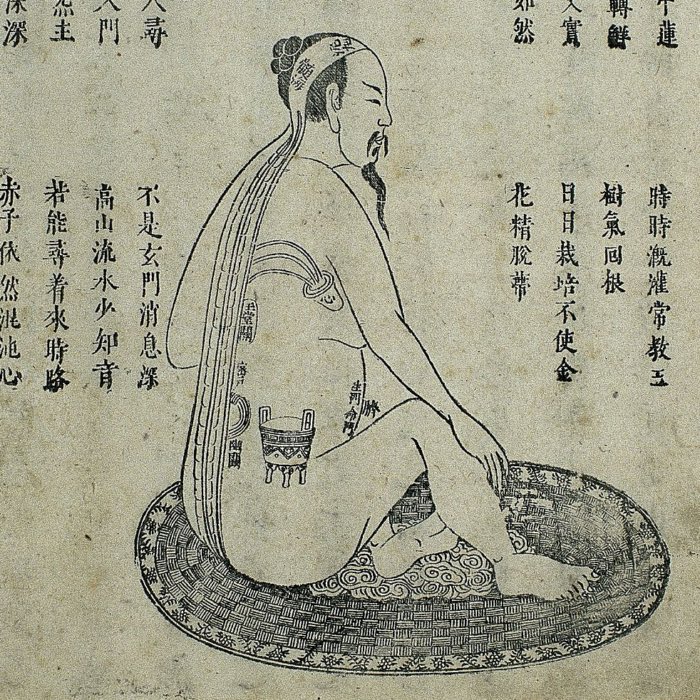

Zhuang Zhou in front of a waterfall. The natural downward flow of water is a common metaphor for naturalness (ziran) in Daoism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Similarly, Daoist themes permeated classical Chinese poetry, notably in the works of poets such as Li Bai and Wang Wei, who celebrated the beauty of nature and the transient nature of human life. Their poetry reflects the Daoist ideal of living in harmony with the natural world and embracing the mystery of existence.

In Japan, these aesthetic principles found expression in the Zen arts. The minimalist design of Zen gardens, with their carefully arranged rocks and raked sand, embodies the Daoist principle of simplicity and naturalness. The Japanese tea ceremony, influenced by Zen, emphasizes mindfulness, spontaneity, and an appreciation for the present moment — qualities aligned with Daoist thought.

Conclusion

The Dao, as a philosophical and cosmological principle, has profoundly shaped the intellectual and cultural history of East Asia. Its influence extends beyond Daoism as a distinct tradition, permeating Confucianism, Buddhism, and indigenous Japanese thought. By emphasizing harmony with the natural order, spontaneity, and the relativity of human perspectives, the Dao offers a unique approach to understanding existence. Its legacy can be seen not only in the philosophical and religious traditions of China, Japan, and beyond but also in their art, literature, and ways of life.

References

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

comments