Chinese philosophy: A brief introduction into major schools of thought and their impact on East Asian culture

Classical Chinese philosophy refers to the rich body of philosophical thought that developed during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) and flourished particularly during the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE) and the Warring States period (475–221 BCE). These eras of political fragmentation and intellectual dynamism witnessed the rise of the “Hundred Schools of Thought”, a term that encompasses the diverse philosophical traditions that sought to address fundamental questions about ethics, governance, human nature, and the cosmos. Among these schools, Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism, Mohism, and later, Buddhism, emerged as the most influential, shaping Chinese cultural and intellectual life and contributed to the development of East Asian philosophical traditions.

Confucius statue at the Confucius Temple, Beijing, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical context

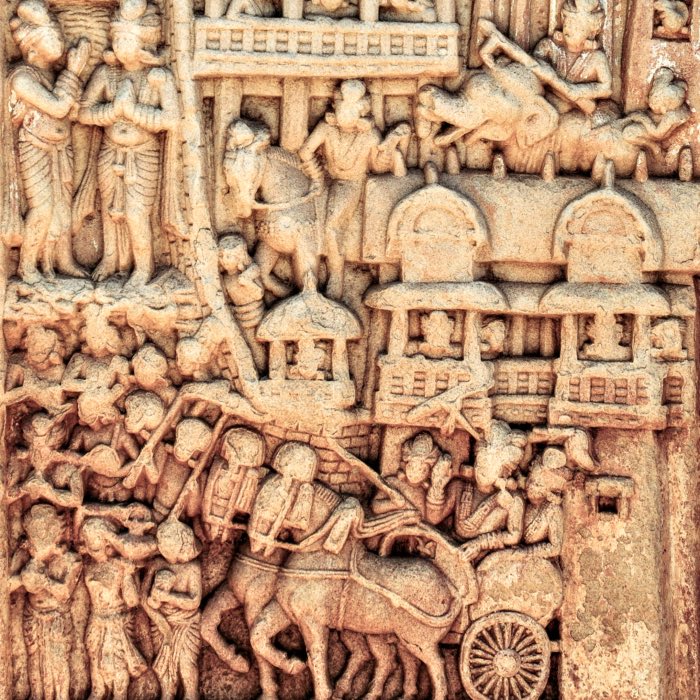

The intellectual ferment of classical Chinese philosophy arose in response to the social and political turmoil of the late Zhou dynasty. As the Zhou kings gradually lost their authority, regional states competed for dominance, leading to widespread conflict and instability. This period of disunity created a fertile environment for philosophical reflection and debate, as thinkers sought to find solutions to the problems of governance, social harmony, and personal conduct.

Philosophers of the time were concerned not only with theoretical questions but also with practical issues of how to create a well-ordered society. Their ideas were often directed at rulers, offering strategies for governance and moral leadership. Unlike in ancient Greece, where philosophy tended to focus on speculative metaphysics, classical Chinese philosophy remained closely tied to questions of ethics and politics.

Major schools of thought

Confucianism

Confucianism, founded by Confucius (551–479 BCE), is perhaps the most well-known school of classical Chinese philosophy. Confucius emphasized the importance of morality, proper conduct, and social harmony. He believed that a well-ordered society could be achieved through the cultivation of virtue (de) and adherence to ritual propriety (li). Central to Confucian thought is the concept of ren (benevolence or humaneness), which underscores the importance of compassion and ethical behavior in human relationships.

Confucius’s teachings were later expanded and systematized by his followers, particularly Mencius (372–289 BCE) and Xunzi (310–235 BCE). While Mencius argued that human nature is inherently good and can be cultivated through education and moral effort, Xunzi took a more pessimistic view, asserting that human nature is fundamentally selfish and must be transformed through rigorous discipline and the enforcement of social norms.

Daoism

Daoism is traditionally associated with the figures of Laozi and Zhuangzi. The foundational text of Daoism, the Dao De Jing (attributed to Laozi), advocates for living in harmony with the Dao (the Way), an ineffable principle that underlies the natural order of the universe. Daoism emphasizes simplicity, spontaneity, and non-action (wu wei), encouraging individuals to align themselves with the natural flow of life rather than striving to control it.

Zhuangzi, a later Daoist philosopher, expanded on these ideas in his eponymous work, the Zhuangzi. Through parables and anecdotes, Zhuangzi challenged conventional wisdom and highlighted the relativity of human perspectives. Daoism, with its focus on naturalness and inner freedom, offered a counterbalance to the more socially oriented philosophy of Confucianism.

Legalism

Legalism, associated with thinkers such as Han Feizi (280–233 BCE) and Shang Yang (390–338 BCE), represents a more pragmatic and authoritarian approach to governance. Legalists believed that human nature is inherently self-interested and that social order can only be maintained through strict laws and harsh punishments. Unlike Confucianism, which emphasized moral leadership, Legalism advocated for a centralized and bureaucratic state where rulers wielded absolute power.

Legalist ideas were instrumental in the unification of China under the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE). While often criticized for their harshness, Legalist principles played a crucial role in the establishment of a strong and centralized state, laying the groundwork for imperial China.

Mohism

Mohism, founded by Mozi (470–391 BCE), offered a distinct alternative to both Confucianism and Daoism. Mozi advocated for universal love (jian ai), arguing that impartial concern for all people would lead to social harmony and reduce conflict. He criticized the Confucian emphasis on ritual and music, viewing them as wasteful and detrimental to social welfare.

In addition to its ethical teachings, Mohism also developed early theories of logic, epistemology, and defensive warfare. Although Mohism declined after the early imperial period, it represents an important strand of classical Chinese thought, particularly in its emphasis on pragmatism and egalitarianism.

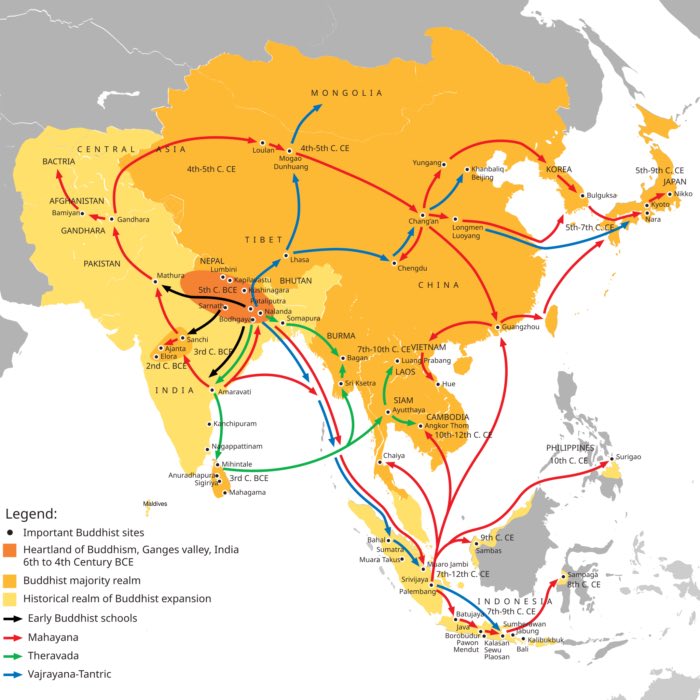

Buddhism

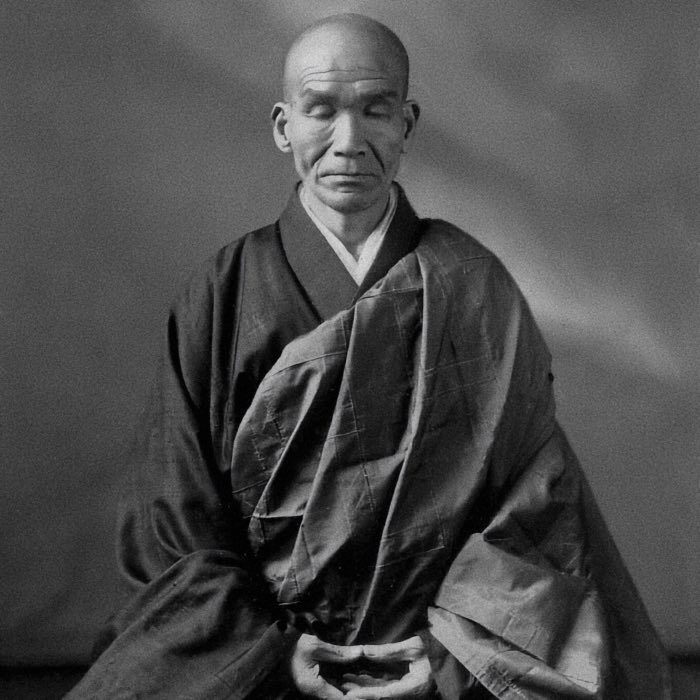

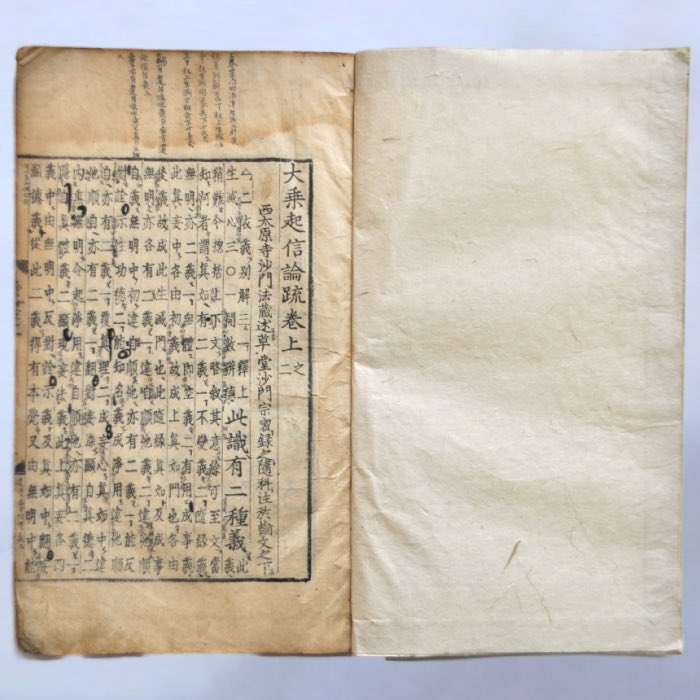

Buddhism, introduced to China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), became a significant philosophical and religious force that deeply influenced Chinese thought. Initially perceived as a foreign doctrine, Buddhism gradually integrated with native traditions, particularly Daoism and Confucianism. By the time of the Six Dynasties period (220–589 CE), distinct Chinese Buddhist schools such as Chán (Zen) Buddhism had emerged.

Chán Buddhism, influenced by Daoist concepts of spontaneity and naturalness, emphasized meditation and direct experience of enlightenment rather than reliance on scriptures or rituals. Over time, Buddhist philosophical ideas, particularly those concerning the nature of suffering, impermanence, and the concept of emptiness (sunyata), contributed to the development of Neo-Confucianism during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), creating a synthesis of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist thought.

Buddhism’s emphasis on compassion, ethical living, and spiritual cultivation resonated with many Chinese intellectuals, further enriching the philosophical landscape of classical China.

Common themes in classical Chinese philosophy

Despite the diversity of the Hundred Schools of Thought, several common themes run through classical Chinese philosophy:

- Ethics and moral cultivation: Most schools emphasized the importance of cultivating virtue and moral character as the foundation for a well-ordered society.

- Governance and social order: Philosophers were deeply concerned with questions of governance, offering different models for achieving stability and harmony.

- Harmony with the natural order: Whether through Confucian ideals of social harmony, Daoist principles of aligning with the Dao, or Buddhist teachings on compassion and non-attachment, classical Chinese philosophy often emphasized living in accordance with natural patterns and rhythms.

- Practical orientation: Unlike Greek philosophy, which often engaged in speculative metaphysics, classical Chinese philosophy tended to focus on practical issues of ethics, politics, and personal conduct.

Comparisons with Greek and Indian philosophy

While Chinese philosophy developed independently, it shares intriguing parallels and contrasts with the philosophical traditions of ancient Greece and India.

Greek philosophy, originating in the 6th century BCE with thinkers such as Thales, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, emphasized rational inquiry, metaphysical speculation, and the search for universal principles. Unlike Chinese philosophy, which often focused on practical governance and ethics, Greek philosophers explored abstract questions about existence, knowledge, and the nature of reality. For example, while Confucius emphasized social harmony and moral virtue, Plato’s philosophy centered on the realm of ideal forms, seeking to understand the true essence beyond physical appearances.

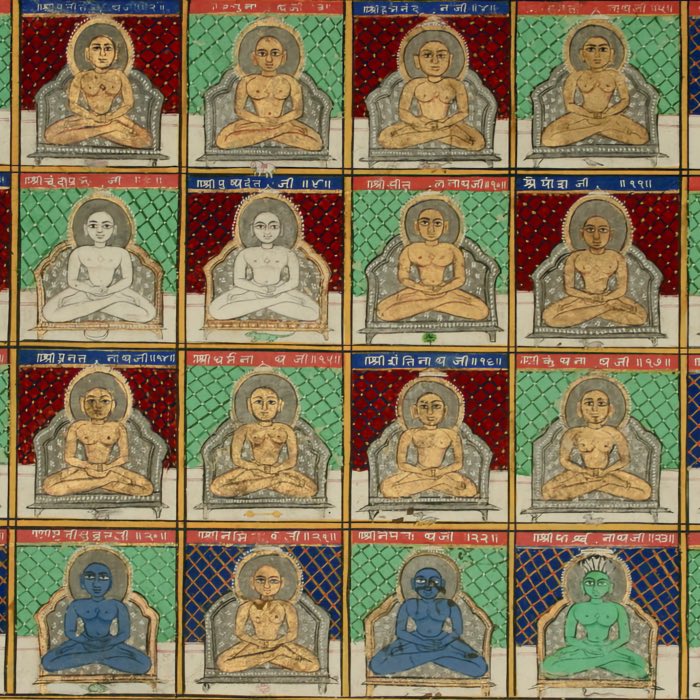

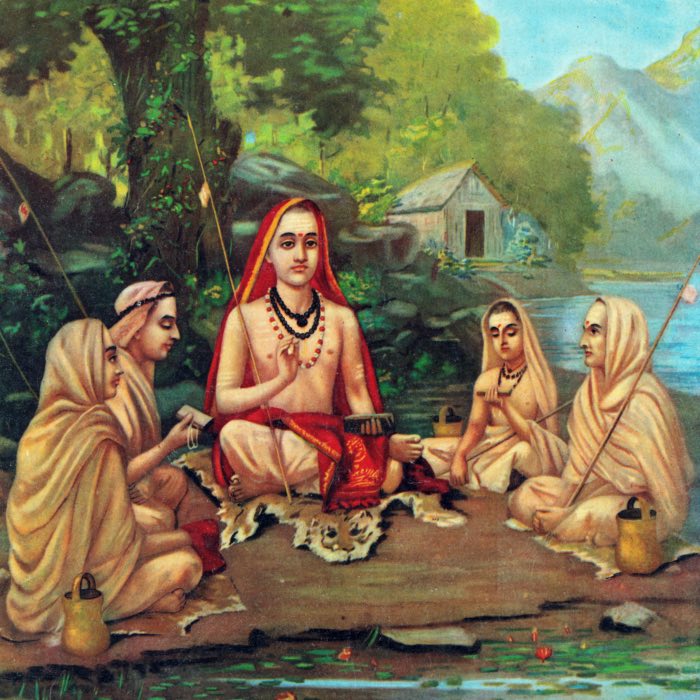

In contrast, Indian philosophy, represented by schools such as Vedanta, Buddhism, and Jainism, also engaged deeply with metaphysical questions but maintained a strong focus on spiritual liberation (moksha or nirvana). Like Daoism and Buddhism in China, Indian thought emphasized the transient nature of the world and the importance of inner spiritual cultivation. However, Indian philosophy placed greater emphasis on meditative practices and asceticism as paths to enlightenment.

Despite these differences, there are notable areas of overlap. Both Chinese and Indian philosophies grappled with the nature of suffering and the means to overcome it. While Indian philosophy developed a rich tradition of dialectical debate and speculative thought, Chinese philosophy leaned toward practical wisdom and harmony with natural and social orders. Similarly, both Chinese and Greek philosophies contributed to political theory — with Aristotle’s Politics and Confucius’s emphasis on virtuous leadership serving as key examples.

Ultimately, while Greek philosophy’s rationalism and speculative nature distinguished it from the more practical orientation of Chinese philosophy, and Indian philosophy’s spiritual focus offered a distinct path, all three traditions sought to answer fundamental questions about existence, ethics, and the human condition.

Influence on East Asian cultures

The philosophical ideas developed in classical China profoundly influenced the cultures of East Asia, including Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Confucianism, in particular, became a cornerstone of social and political life in these regions, shaping systems of education, governance, and family structure. The Confucian emphasis on hierarchy, filial piety, and ethical conduct was integrated into the state ideologies of Korea’s Joseon dynasty and Japan’s Tokugawa shogunate.

Daoist thought, with its emphasis on harmony with nature and inner cultivation, also permeated East Asian religious practices, arts, and literature. In Japan, Daoist ideas merged with indigenous Shinto beliefs, contributing to the development of unique aesthetic principles, such as wabi-sabi (the beauty of imperfection) and ma (the space between elements).

Buddhism, having entered China from India, subsequently spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, where it adapted to local cultures and gave rise to distinct schools, such as Zen Buddhism in Japan and Seon Buddhism in Korea. These traditions retained the core philosophical teachings of Buddhism while integrating elements of native philosophies and practices.

The synthesis of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism in China provided a model for similar intellectual and cultural syntheses in neighboring countries. This blending of philosophical traditions contributed to a shared East Asian cultural heritage that continues to influence contemporary thought, art, and social values.

Conclusion

Classical Chinese philosophy has profoundly influenced Chinese culture, society, and governance. Confucianism shaped imperial China’s education and statecraft, Daoism enriched religious practices and the arts, and Legalism established a framework for centralized rule. The synthesis of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhism ideas during the later imperial period led to Neo-Confucianism, a major intellectual movement that shaped Chinese thought for centuries.

Beyond China, classical Chinese philosophy played a crucial role in shaping East Asian cultures. Confucian ethics influenced governance in Korea and Japan, while Daoist and Buddhist ideas merged with local traditions, contributing to the region’s shared intellectual heritage.

When compared to Greek and Indian philosophies, Chinese thought stands out for its practical focus on governance and ethics. While Greek philosophy emphasized rational inquiry and metaphysics, and Indian philosophy pursued spiritual liberation, Chinese philosophy prioritized moral cultivation and social harmony. Despite their differences, all three traditions addressed fundamental questions about existence and ethics, leaving a lasting impact on global intellectual history.

Today, classical Chinese philosophy continues to inspire discussions on ethics, governance, and human-nature relationships. Its legacy is evident in both East Asia and global philosophical thought, offering timeless frameworks for ethical conduct and social harmony.

References

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

- Augustin, Birgitta, “Daoism and Daoist Art””, 2000, In: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, linkꜛ

- Denise Patry, Donna K. Strahan, & Lawrence Becker, Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010, Book, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300155211

- Otto Ladstätter, Sepp Linhart, Anna Stangl, China und Japan: Die Kulturen Ostasiens, 1983, Carl Ueberreuter Verlag, ISBN-13: 978-3800031733

- Marsha Smith Weidner, Cultural intersections in later Chinese Buddhism, 2001, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824823085

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Keown, Damien, A dictionary of Buddhism, 2003, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-19-860560-7

- Notz, Lexikon des Buddhismus, 2002, Marixverlag, ISBN-10: 3932412087

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

comments