Emergence of Buddhism in China

Buddhism, originating in India around the 5th century BCE, began to spread into China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Over the next several centuries, it evolved into a distinctly Chinese form of spirituality by blending with indigenous philosophical systems such as Daoism and Confucianism. The emergence of Buddhism in China represents one of the most significant cultural and intellectual transformations in Chinese history, influencing art, literature, governance, and daily life.

The Big Vairocana of Longmen Buddha Grottoes, Luoyang, Henan, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Historical context of Buddhism’s arrival in China

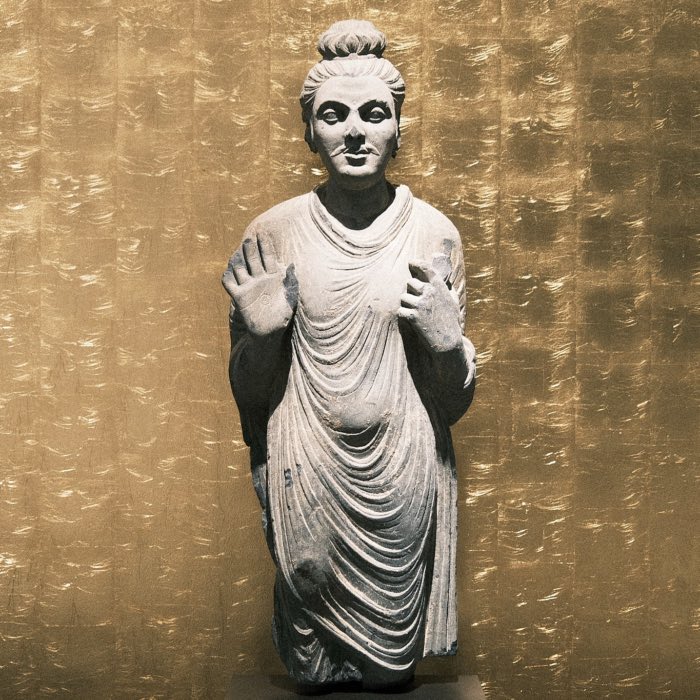

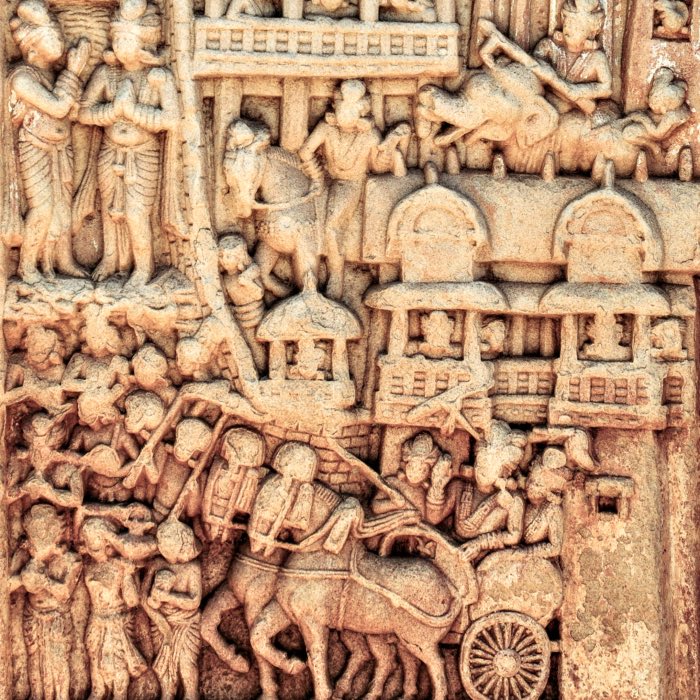

Buddhism is believed to have entered China through the Silk Road, the network of trade routes connecting China to Central Asia, India, and the Mediterranean. By the 1st century CE, merchants, missionaries, and travelers from India and Central Asia began to introduce Buddhist texts, images, and practices to Chinese society.

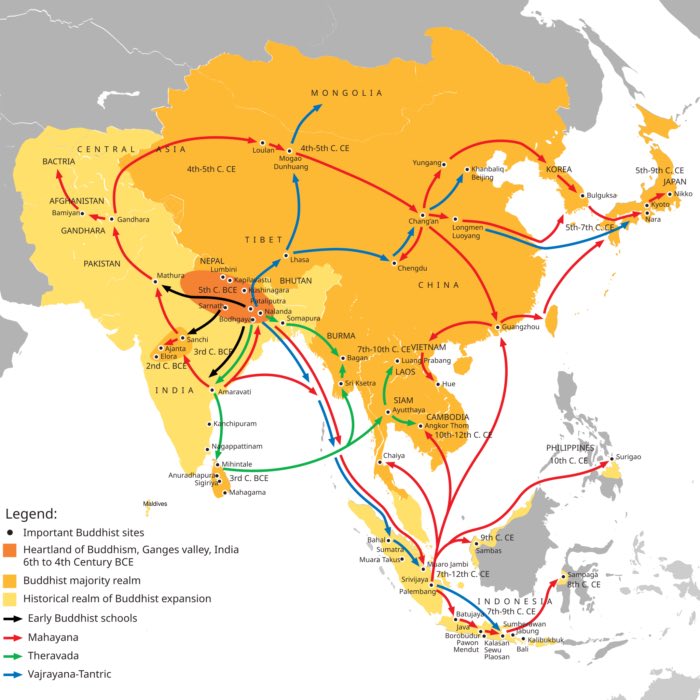

Buddhist expansion in Asia: Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Chinese Empire (Han dynasty) through the Silk Road during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, forming what scholars have called the “great circle of Buddhism”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The early Chinese reception of Buddhism was mixed. Initially, Buddhism was viewed as a foreign and exotic religion, distinct from the established indigenous traditions of Daoism and Confucianism. However, as Buddhist monks began to translate key scriptures and adapt their teachings to the Chinese worldview, Buddhism gained a foothold among intellectuals and the ruling elite.

White Horse Temple in Luoyang, one of the earliest Chinese Buddhist temples. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

During the late Han dynasty and the subsequent period of political fragmentation known as the Six Dynasties (220–589 CE), Buddhism offered solace and spiritual guidance in a time of chaos and uncertainty. The religion’s emphasis on personal salvation, meditation, and compassion resonated with those seeking an alternative to the rigid social hierarchies of Confucianism and the mystical naturalism of Daoism.

Guangyou Temple at Liaoyang, Liaoning. Rebuilt in 2002. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Factors facilitating the spread of Buddhism in China

Several factors contributed to the successful spread of Buddhism in China:

Translation efforts

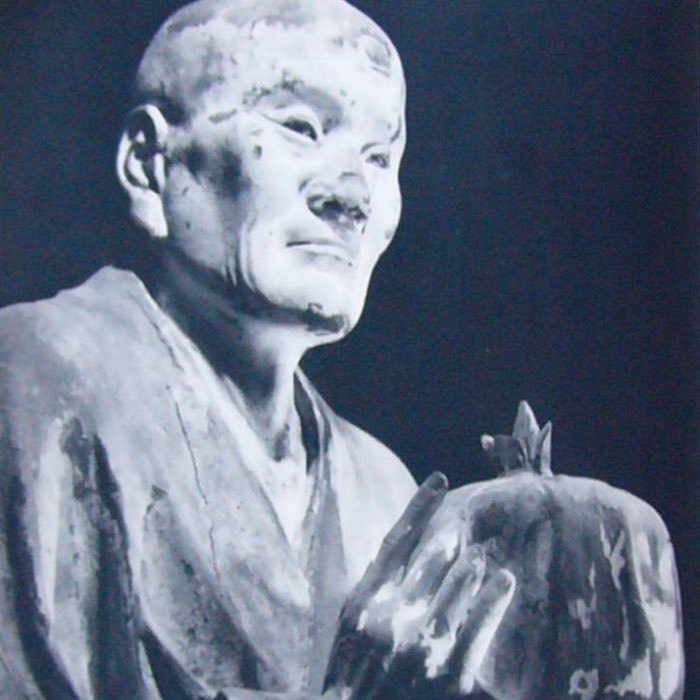

The translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese was a crucial step in making the religion accessible to the Chinese population. Prominent translators such as An Shigao (2nd century CE), Kumarajiva (4th–5th century CE), and Xuanzang (7th century CE) played a pivotal role in this process. They not only translated texts but also interpreted and adapted Buddhist ideas to align with Chinese cultural norms.

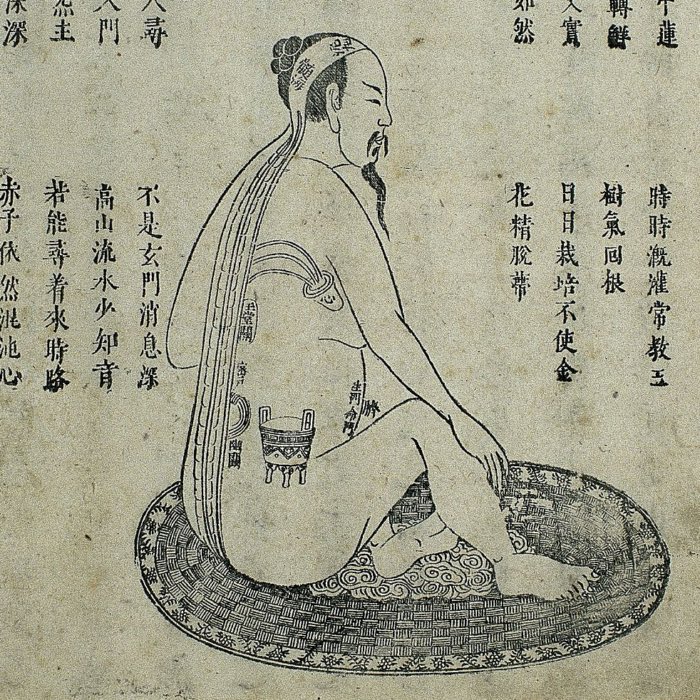

Syncretism with Daoism

Early Buddhist missionaries often used Daoist terminology to explain Buddhist concepts. For example, nirvana was equated with the Dao, and wu wei (effortless action) was linked to Buddhist non-attachment. This syncretism facilitated the acceptance of Buddhism by Daoist practitioners and intellectuals.

Imperial patronage

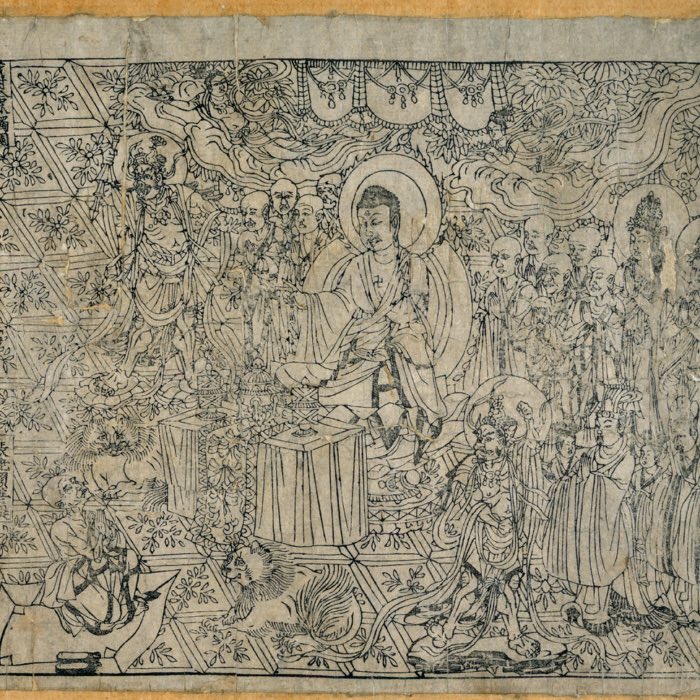

Several Chinese emperors supported Buddhism, viewing it as a means of unifying the country and promoting moral order. The Northern Wei dynasty (386–534 CE) and the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) were particularly notable for their patronage of Buddhist institutions, leading to the construction of monasteries, temples, and iconic cave complexes such as those at Dunhuang and Longmen.

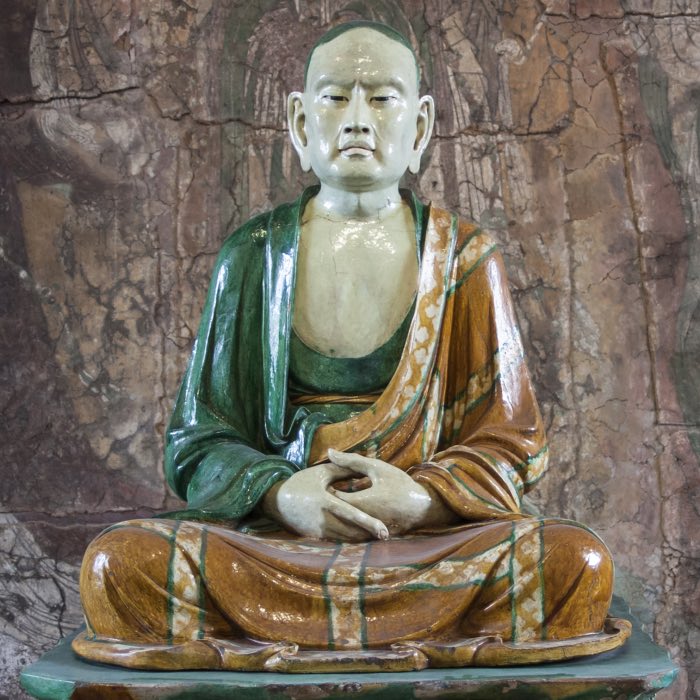

Monastic system

The establishment of monasteries provided a structured institution for the dissemination of Buddhist teachings. Monasteries served not only as religious centers but also as places of learning, medicine, and social welfare, further integrating Buddhism into Chinese society.

Buddhist Monks at Kunming Yuantong Temple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Buddhist monastics and laypeople chanting sutras in the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple, Singapore. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Traditional Buddhist ceremony in Hangzhou, Zhejiang. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Development of Chinese Buddhist schools

As Buddhism spread throughout China, it developed distinct schools of thought that reflected the Chinese philosophical and cultural context. Some of the most influential Chinese Buddhist schools include:

Sanlun school (3rd century CE)

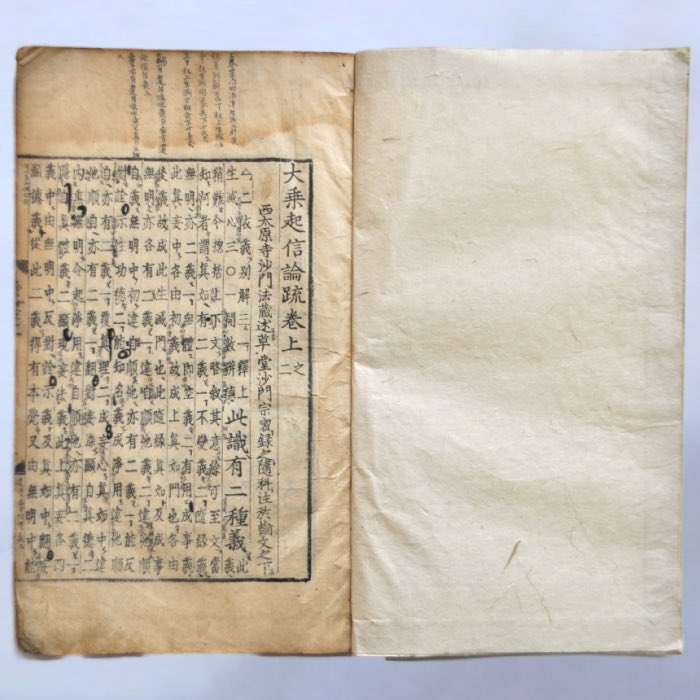

The Sanlun (Three Treatises) school was one of the earliest Chinese Buddhist schools, introduced by the famous monk Kumārajīva during the late 3rd to early 4th century CE. It is based on the teachings of Nagarjuna, particularly his Madhyamaka (Middle Way) philosophy, and emphasizes the doctrine of emptiness (shunyata). According to Sanlun thought, all phenomena lack inherent existence, and enlightenment comes from realizing the middle way between extremes of existence and non-existence.

The Sanlun school played a significant role in the initial spread of Mahayana Buddhism in China, influencing later schools such as Tiantai and Huayan.

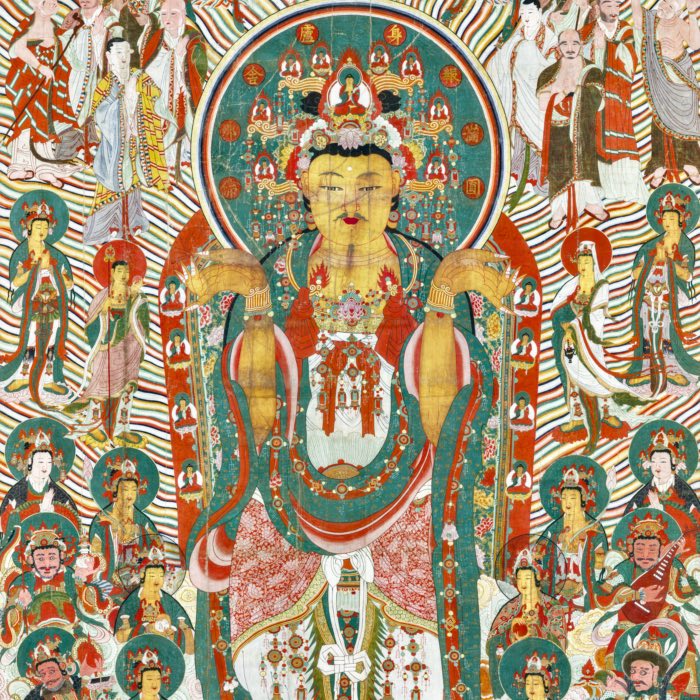

Pure Land Buddhism (4th century CE)

Pure Land Buddhism, focused on devotion to Amitabha Buddha and the aspiration to be reborn in the Western Pure Land (Sukhavati), became one of the most popular forms of Buddhism in China. It offered a simple and accessible path to salvation through faith and chanting the name of Amitabha (nianfo, 念佛).

Pure Land teachings appealed to the general populace, providing hope and comfort in difficult times. Its emphasis on devotion and grace complemented the more rigorous meditative practices of other schools.

Vinaya school (4th century CE)

The Vinaya school, also known as the Lü school, was founded by the monk Daoxuan during the late 4th century CE. It focuses on the study and practice of the vinaya (monastic code), emphasizing strict adherence to monastic discipline as the foundation for spiritual practice.

The school played a critical role in shaping the monastic tradition in China, ensuring the proper conduct of monks and nuns, and laying the groundwork for a stable Buddhist community. Although the Vinaya school eventually declined as a distinct school, its teachings were incorporated into other major traditions.

Tiantai school (6th century CE)

The Tiantai school, founded by Zhiyi (538–597 CE), is known for its comprehensive and systematic approach to Buddhist doctrine. It emphasizes the Lotus Sutra as the highest teaching of the Buddha and advocates for a balanced practice of meditation, ethical conduct, and intellectual study.

Tiantai philosophy is notable for its doctrine of the “Three Truths” (san di, 三諦): emptiness, conventional existence, and the Middle Way, which integrates these two perspectives. This synthesis reflects the influence of Chinese intellectual traditions on Buddhist thought.

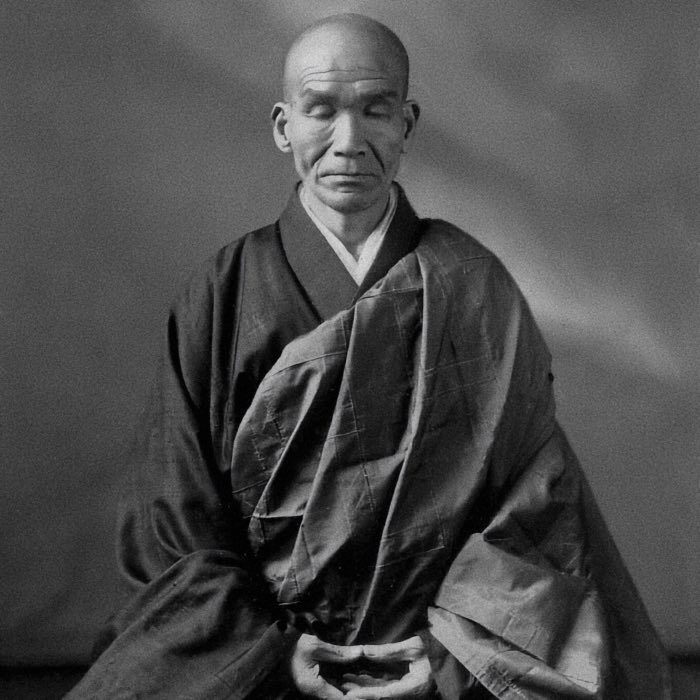

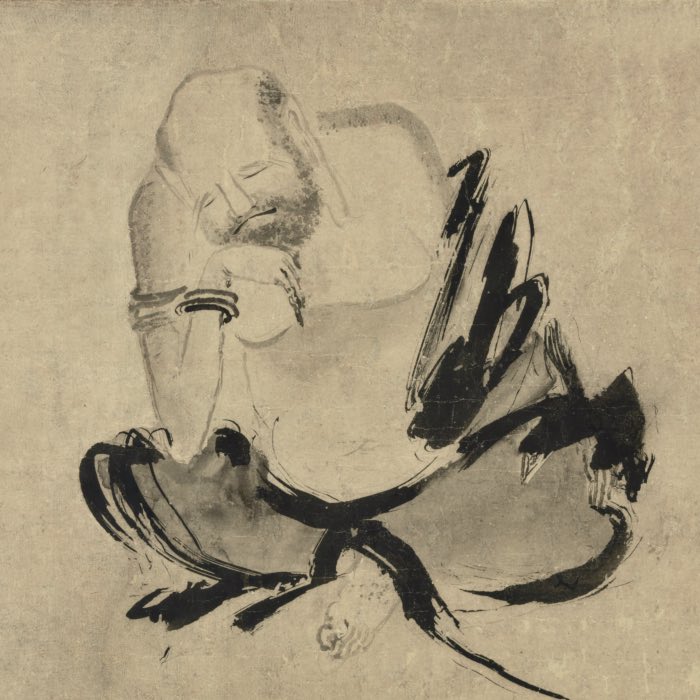

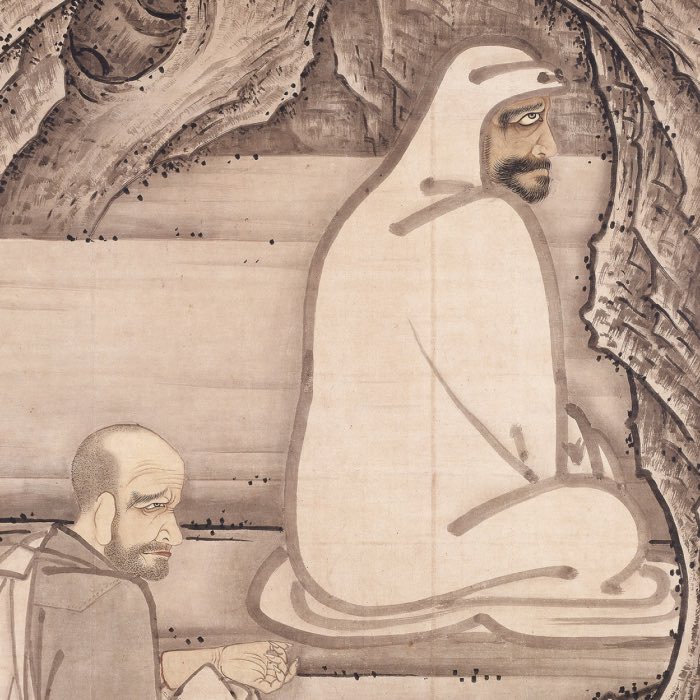

Chán Buddhism (6th century CE)

Chán Buddhism, known as Zen in Japan, emerged during the 6th century CE and became one of the most influential schools of Chinese Buddhism. It emphasizes direct experience and meditation over intellectual study of scriptures. Chán teachings often highlight sudden enlightenment (wu, 悟) and the use of paradoxical anecdotes (kōan) to transcend rational thinking.

Chán Buddhism was heavily influenced by Daoist principles, particularly the idea of natural spontaneity (ziran) and harmony with the Dao. Its simple and intuitive approach resonated with Chinese aesthetics and culture, leading to its widespread popularity.

Huayan school (7th century CE)

The Huayan school, based on the Avatamsaka Sutra (Huayan Jing, 華嚴經), developed a cosmological vision of interdependence and mutual causality. It presents the idea that all phenomena are interconnected and contain the essence of the whole.

The Huayan school’s doctrine of the “Indra’s Net” metaphorically describes the universe as a vast net of jewels, each reflecting all others, symbolizing the interconnectedness of all things. This holistic worldview had a profound influence on Chinese philosophy, art, and later Buddhist schools.

Faxiang school (7th century CE)

The Faxiang (Dharma Characteristics) school, also known as the Yogācāra or Consciousness-Only school, was founded by the eminent monk Xuanzang upon his return from India in the 7th century CE. Drawing on the works of Indian Yogācāra masters such as Vasubandhu and Asanga, the Faxiang school focuses on the nature of consciousness, arguing that all perceived reality is a projection of the mind.

The school developed a detailed classification of mental functions and philosophical arguments about perception and reality, contributing significantly to Buddhist epistemology in China.

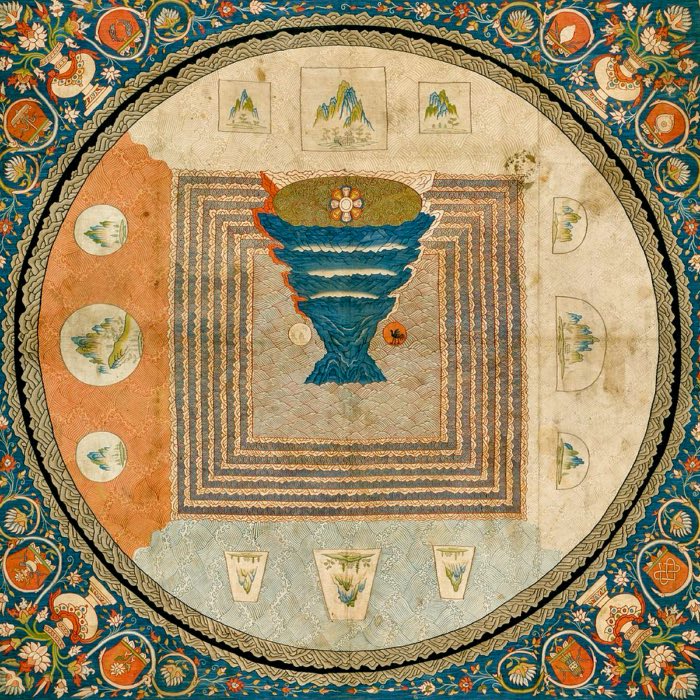

Zhenyan school (8th century CE)

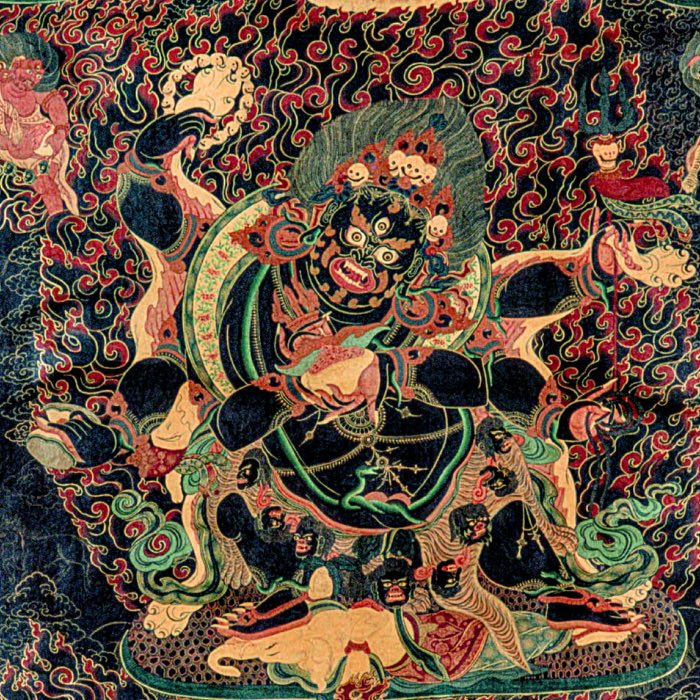

The Zhenyan (True Word) school, a form of Esoteric or Tantric Buddhism, was introduced to China during the Tang dynasty in the 8th century CE. It focuses on ritual practices, including mantra recitation, mudras (hand gestures), and mandalas, aimed at achieving spiritual transformation and enlightenment.

Although the Zhenyan school did not flourish in China as it did in Japan (where it became the Shingon school), it had a lasting influence on Chinese Buddhist rituals and iconography.

Buddha statues at the Mahavira Hall of Baoning Temple, Hunan, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Interaction with Daoism and Confucianism

Buddhism’s introduction into China led to significant interactions and mutual influences with Daoism and Confucianism, resulting in both conflict and synthesis.

With Daoism

Early Buddhist missionaries adopted Daoist language and concepts to convey Buddhist ideas, leading to a period of syncretism. Over time, however, tensions arose as both traditions competed for imperial patronage and influence. Despite this, Daoism and Buddhism shared many common themes, such as meditation, the pursuit of immortality, and harmony with nature, leading to mutual enrichment.

With Confucianism

Initially, Confucian scholars were critical of Buddhism, viewing it as foreign and disruptive to traditional family values. However, during the Tang and Song dynasties, Neo-Confucianism emerged, incorporating elements of Buddhist metaphysics and Daoist cosmology into a Confucian ethical framework. This synthesis shaped the intellectual landscape of China for centuries.

Impact of Buddhism on Chinese culture

Buddhism had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese culture, influencing various aspects of life.

In arts and architecture, Buddhist art flourished, leading to the creation of statues, murals, and cave complexes that are still admired today. Iconic sites such as the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang and the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang bear testament to the rich artistic heritage inspired by Buddhism (see e.g. my post the Kizil Caves to get an impression of the art in the these caves). These sites not only served as religious sanctuaries but also as cultural hubs where art and spirituality intersected.

The Spring Temple Buddha, a colossal statue of Vairocana, in Henan, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Literature in China was also deeply influenced by Buddhist themes and ideas. Chinese poetry, prose, and philosophical writings often reflected Buddhist concepts. Renowned poets like Wang Wei and Li Bai drew inspiration from Buddhist notions of impermanence and enlightenment, weaving these themes into their works and enriching Chinese literary tradition.

Ethics and philosophy in China were significantly shaped by Buddhist teachings. Buddhism introduced new ethical ideals, such as compassion for all sentient beings and the pursuit of personal enlightenment. These principles complemented and sometimes challenged existing Confucian and Daoist values. Additionally, Buddhism enriched Chinese philosophical discourse by introducing concepts such as emptiness (shunyata) and dependent origination (pratityasamutpada), which offered new perspectives on existence and the nature of reality.

Overall, the integration of Buddhism into Chinese culture led to a dynamic and multifaceted transformation, leaving a lasting legacy on the nation’s artistic, literary, and philosophical landscapes.

Conclusion

The emergence of Buddhism in China represents a remarkable period of cultural and intellectual exchange, resulting in the creation of a uniquely Chinese form of Buddhism that integrated Indian spiritual teachings with indigenous Chinese philosophy. Over time, Buddhism became deeply embedded in Chinese society, influencing its art, literature, governance, and daily life.

The interaction between Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism shaped the development of Chinese thought, creating a rich and diverse intellectual tradition. Today, Chinese Buddhism remains a dynamic spiritual way, practiced by millions of people in China and around the world.

The Jing’an Temple in Shanghai, a modern Chinese Esoteric tradition temple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

References

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Denise Patry, Donna K. Strahan, & Lawrence Becker, Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010, Book, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300155211

- Otto Ladstätter, Sepp Linhart, Anna Stangl, China und Japan: Die Kulturen Ostasiens, 1983, Carl Ueberreuter Verlag, ISBN-13: 978-3800031733

- Marsha Smith Weidner, Cultural intersections in later Chinese Buddhism, 2001, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824823085

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Keown, Damien, A dictionary of Buddhism, 2003, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-19-860560-7

- Notz, Lexikon des Buddhismus, 2002, Marixverlag, ISBN-10: 3932412087

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

comments