Chang: The Daoist concept of constancy and perpetual transformation

The concept of Chang (常), often translated as “constancy” or “permanence”, occupies a nuanced position in Daoist philosophy. At first glance, Chang may seem paradoxical in the context of Daoism, which emphasizes flux, impermanence, and the continuous transformation of all things. However, in Daoist thought, Chang refers to the underlying constancy of the Dao itself — a principle that persists amidst the ceaseless changes of the phenomenal world. It represents the enduring nature of the Dao as the source and pattern of all existence. This post explores the philosophical foundations of Chang, its relationship with transformation (hua, 化), and its implications for Daoist ethics, cosmology, and personal cultivation.

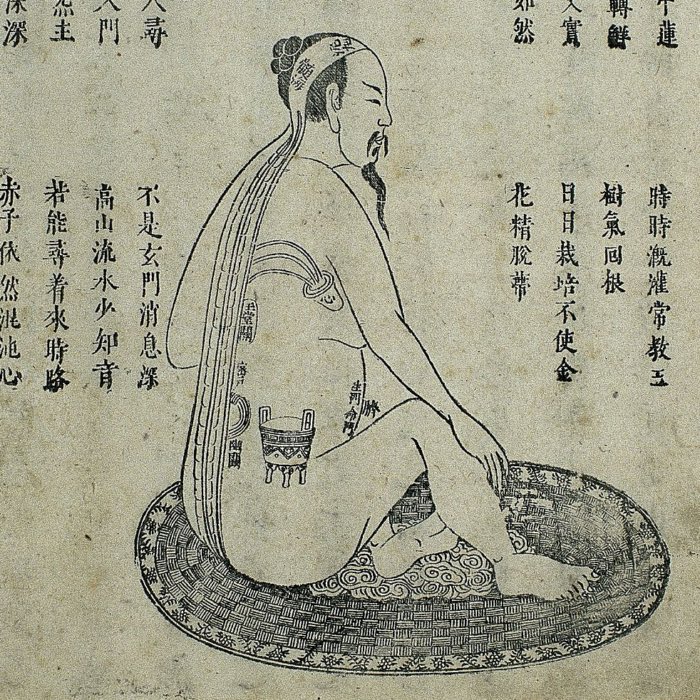

Inquiring of the Dao at the Cave of Paradise, hanging scroll, color on silk. This painting is based on the story that the Yellow Emperor went out to the Kongtong Mountains to meet with the famous Daoist sage Guangchengzi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (public domain)

Philosophical foundations of Chang

In the Dao De Jing, Laozi frequently emphasizes the constancy of the Dao, describing it as the eternal principle that underlies and sustains all things. In Chapter 1, he states, “The Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao. The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” Here, Chang refers to the Dao’s unchanging essence, which transcends the transient world of names and forms.

While the manifestations of the Dao — the “Ten Thousand Things” — are subject to continuous change, the Dao itself remains constant. This constancy is not static or fixed but represents the unbroken continuity of the Dao’s process of creation and transformation. Thus, Chang in Daoism signifies the ever-present, underlying reality that endures even as the external world fluctuates.

The apparent paradox of Chang and change reflects a key Daoist insight: while everything in the world is impermanent and subject to transformation, there is a deeper order or pattern that remains constant. This perspective invites a holistic understanding of reality, where permanence and impermanence, constancy and transformation, coexist in a dynamic interplay.

Chang and transformation (hua)

In Daoist cosmology, hua (transformation) is the fundamental process through which the Dao expresses itself in the world. All things are in a constant state of flux, transforming from one form to another in accordance with the natural rhythms of the Dao. Seasons change, life and death follow each other in an endless cycle, and even the seemingly solid mountains are eventually worn down by time.

However, amidst this continuous transformation, there is a constancy in the way change occurs. The cycles of nature — day and night, the changing seasons, birth and death — follow predictable patterns that reflect the enduring nature of the Dao. This constancy of transformation is what Daoism refers to as Chang. It represents the idea that while specific forms may change, the underlying process remains constant.

Zhuangzi elaborates on this idea by emphasizing the relativity of change. In the Zhuangzi, he presents numerous stories and parables that illustrate how what appears to be a permanent state is merely a temporary phase in an ongoing process of transformation. For Zhuangzi, wisdom lies in recognizing the constancy of change and embracing it rather than clinging to fixed forms or identities.

Ethical implications of Chang

The Daoist concept of Chang has significant ethical implications. By recognizing the constancy of the Dao amidst the flux of life, individuals can cultivate a sense of equanimity and acceptance in the face of change. This ethical stance is closely related to the Daoist principles of wu wei (effortless action) and ziran (naturalness), which encourage living in harmony with the natural order.

Daoist ethics do not advocate for rigid adherence to moral rules but for a flexible, adaptive approach that responds to the ever-changing circumstances of life. However, this adaptability is grounded in a deeper constancy — the enduring values of simplicity, humility, and harmony with the Dao. By embodying these values, individuals can navigate life’s changes with grace and balance.

Furthermore, the recognition of Chang as the constant process of transformation fosters an ethic of non-attachment. Since all things are subject to change, clinging to specific outcomes or forms leads to suffering. Daoist sages, who embody Chang, cultivate a state of inner tranquility and openness, allowing them to flow with life’s changes rather than resisting them.

Chang in personal cultivation

In personal cultivation, the Daoist ideal of Chang involves aligning oneself with the enduring rhythms of the Dao while embracing the inevitable changes of life. This process involves both internal and external practices aimed at harmonizing the body, mind, and spirit with the Dao.

Meditation, for example, helps practitioners cultivate a sense of inner constancy by quieting the mind and fostering a connection with the unchanging essence of the Dao. Breath control and energy cultivation practices, such as Qigong and Tai Chi, promote physical and mental balance by aligning the practitioner’s Qi with the natural rhythms of the cosmos.

In advanced Daoist practices, such as internal alchemy (neidan), the concept of Chang is reflected in the goal of achieving spiritual immortality. This immortality is not a literal escape from death but a transcendence of ordinary existence through the realization of one’s unity with the Dao. By cultivating Chang within themselves, practitioners aim to harmonize with the eternal process of transformation and attain a state of inner permanence amidst life’s changes.

Chang in Daoist cosmology and the arts

In Daoist cosmology, the constancy of the Dao is reflected in the harmonious patterns of nature. The alternation of yin and yang, the cycles of the seasons, and the flow of rivers all exemplify the interplay of change and constancy. By observing these natural rhythms, Daoist practitioners seek to attune themselves to the Dao and live in accordance with its enduring principles.

This cosmological perspective also informs Daoist aesthetics, which value simplicity, naturalness, and spontaneity. In Chinese landscape painting, for example, artists often depict scenes that evoke a sense of timelessness, such as mountains, rivers, and ancient trees. These elements symbolize the enduring nature of the Dao amidst the transient world of human affairs.

Daoist poetry similarly reflects the ideal of Chang by celebrating the constancy of nature’s rhythms and the beauty of life’s impermanence. Poets such as Wang Wei and Li Bai often juxtapose images of fleeting moments — such as falling leaves or drifting clouds — with the enduring presence of mountains and rivers, inviting readers to contemplate the constancy of change and the timeless nature of the Dao.

Conclusion

The Daoist concept of Chang, or constancy, offers a profound perspective on the nature of reality as a dynamic interplay between permanence and impermanence. While all things are subject to continuous transformation, there is an underlying constancy in the way these changes unfold — a constancy rooted in the Dao itself. By recognizing and embracing Chang, Daoists believe that they can cultivate a sense of inner peace, adaptability, and harmony with the world. This ethical and philosophical ideal has influenced Daoist practices, personal cultivation, and Chinese art and literature, providing a timeless framework for understanding and navigating life’s inevitable changes.

References

- Slingerland, Edward, Effortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195314878

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing - , Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

comments