The Canaanite religion – and its influence on early Judaism

The Canaanite religion, a rich and complex polytheistic tradition, played a foundational role in the religious and cultural landscape of the ancient Levant. Rooted in a pantheon of deities that governed various aspects of life and nature, Canaanite religion was deeply intertwined with agricultural cycles, cosmic order, and political authority. Its myths, rituals, and theological constructs did not vanish with the emergence of new religious traditions but rather permeated and influenced them, including the early development of Judaism.

The Canaanite religious worldview

The Canaanite religion revolved around a pantheon of gods and goddesses who presided over various aspects of nature, human society, and the cosmos. At its head was El, the patriarchal creator deity, often depicted as a wise and benevolent figure presiding over the assembly of the gods. His consort, Asherah, was venerated as a mother goddess, associated with fertility and the sea. Other significant deities included Baal, the storm god who brought rain and agricultural fertility; Anat, a warrior goddess known for her ferocity; and Astarte, a goddess of love and war.

Left: Gilded statuette of El from Ugarit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Asherah statue, 8th c. BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: Bronze Statuette of Seated God Ba’al, Hazor, 15th-13th century BCE, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel. Ba’al was a prominent deity in the Canaanite pantheon and influenced early Israelite religion. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0) – Right: Male votive figure of Baal. This solid cast bronze figurine served as a votive offering, and represents the Canaanite war god, Baal, bringer of the autumnal rains and suppressor of the destructive flood waters. He probably wore a gold skirt and may have carried a mace in one of his clenched fists. Early 2nd millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Canaanite religion was deeply tied to agricultural cycles and the rhythms of the natural world. Baal’s mythological battles against Yam (the sea) and Mot (death) symbolized the struggle between life-sustaining forces and destructive chaos. These myths were not mere stories but were enacted in rituals that sought to align human activity with divine will and secure the favor of the gods.

Left: Figure of Ba’al with raised arm, 14th–12th century BCE, found at Ugarit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Baal with Thunderbolt or the Baal stele, white limestone bas-relief, Ugarit, 15 c. BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Temples and high places (bamot) were central to Canaanite worship, serving as venues for sacrifices, offerings, and communal gatherings. Religious artifacts, including figurines, altars, and inscriptions, provide evidence of widespread devotion and elaborate ritual practices across the Canaanite city-states.

Canaanite influence on early Israelite religion

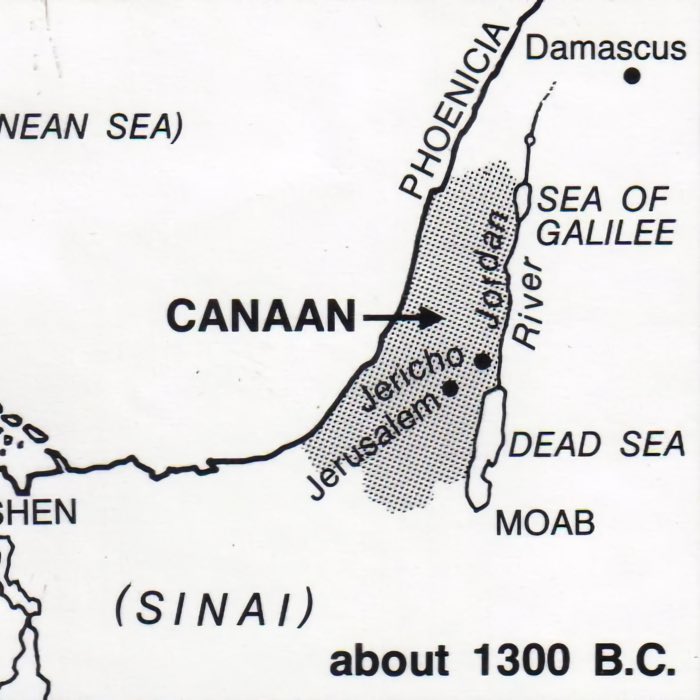

The early Israelites emerged in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age (circa 1200 BCE) as a distinct group within the Levant, sharing cultural and linguistic ties with their Canaanite neighbors. Archaeological evidence, including settlements in the central highlands of Canaan, suggests that the Israelites were originally part of the broader Canaanite cultural milieu before developing a distinct identity. This shared cultural space facilitated extensive interaction, as reflected in early Israelite religious practices that were initially similar to those of their Canaanite neighbors. The Hebrew Bible acknowledges this common heritage, portraying the Israelites as descendants of patriarchs who dwelt in Canaan and interacted with its peoples and gods.

El and Yahweh

The name of the Canaanite high god, El, is preserved in early Israelite religion. Titles such as El Shaddai and El Elyon, used for the God of Israel in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Deuteronomy 32:8-9), reflect the linguistic and theological continuity between Canaanite and Israelite traditions. Initially characterized by monolatry — the worship of one god, Yahweh, while acknowledging the existence of other deities — early Israelite religion shows evidence of Yahweh’s origins possibly being linked to southern desert regions, such as Midian or Edom. In these areas, Yahweh may have been associated with storm and warrior attributes.

As the Israelites settled in Canaan, their worship of Yahweh absorbed and adapted elements of the Canaanite religious tradition. The association of Yahweh with attributes of El and Baal is evident in biblical texts, where Yahweh is described as a creator, king, and storm god. This process of integration and reinterpretation highlights the syncretic development of Israelite theology, culminating in the identification of Yahweh as the supreme deity.

Asherah and the role of the divine feminine

Archaeological discoveries, such as inscriptions from Kuntillet Ajrud and Khirbet el-Qom, suggest that Asherah may have been venerated alongside Yahweh in early Israelite religion. These inscriptions include phrases such as “Yahweh and his Asherah”, indicating a complex relationship between Canaanite and Israelite religious practices. While the worship of Asherah was later condemned in biblical texts, her early presence underscores the influence of Canaanite theology on Israelite conceptions of the divine.

Baal and the struggle for monotheism

The Hebrew Bible often portrays Baal worship as a primary adversary of Yahwism, particularly during the monarchy. Prophetic texts, such as those of Elijah and Hosea, reflect a polemic against Baal that sought to establish Yahweh as the sole legitimate deity. However, the biblical emphasis on Baal as a rival god reveals the enduring appeal of Baal worship among the Israelites, illustrating the challenge of transitioning from polytheism to monotheism.

Ritual and sacrifice

Many Israelite rituals, including animal sacrifices, grain offerings, and the use of altars, bear striking similarities to Canaanite practices. The institution of the bamot as local places of worship persisted in early Israelite religion despite later efforts to centralize worship in Jerusalem. The shared ritual vocabulary reflects the deep roots of Israelite practices in the Canaanite religious tradition.

Theological and mythological adaptations

The process of adapting Canaanite religious ideas into the emerging framework of Judaism involved significant theological and mythological reinterpretation. The Israelite emphasis on the exclusive worship of Yahweh necessitated the demotion or outright rejection of other deities. Myths that once depicted the interactions of multiple gods were reframed to emphasize Yahweh’s supremacy and unique role as the creator and sustainer of the cosmos.

The biblical account of creation, for example, reflects echoes of Canaanite cosmology while presenting a radically monotheistic perspective. The portrayal of Yahweh subduing chaotic forces, such as the waters of the deep (tehom), recalls Baal’s battles with Yam and Mot. However, in the biblical narrative, these forces are entirely subordinate to Yahweh, underscoring his unparalleled authority.

The concept of covenant, central to Israelite theology, may also have Canaanite antecedents. Treaties and agreements between gods and their followers, a common feature of Canaanite religion, were adapted into the Israelite understanding of their unique relationship with Yahweh. The covenantal framework transformed these earlier traditions into a theological foundation for Israel’s identity and mission.

Shift to monotheism and the rejection of Canaanite religion

The transition from the polytheism of Canaan to the monotheism of Judaism was not an immediate or uniform process. Biblical texts document a prolonged struggle to establish exclusive Yahwism, with frequent denunciations of idolatry and syncretism. The Deuteronomic reforms, particularly those under King Josiah, represent a decisive effort to centralize worship in Jerusalem and eliminate Canaanite influences.

This rejection, however, did not erase the Canaanite legacy. Many aspects of Canaanite religion were absorbed and transformed within the Israelite tradition, providing a foundation for the theological innovations that defined Judaism. The tension between continuity and discontinuity in this process highlights the complexity of religious development in the ancient Near East.

Conclusion

The Canaanite religion profoundly influenced the early development of Judaism, shaping its language, rituals, and theological constructs. While Judaism ultimately diverged from Canaanite polytheism to embrace monotheism, it did so through a process of adaptation and reinterpretation that preserved key elements of its cultural and religious heritage. The Canaanite gods and goddesses, once central to the religious life of the Levant, continued to exert their influence on the evolving religious landscape of the region, leaving an enduring legacy that resonates in the texts and traditions of Judaism and Christianity.

References and further reading

- Coogan, M. D., Stories from ancient Canaan, 2012, Westminster Press, ISBN: 978-0664232429

- Pardee, D., Ritual and cult at Ugarit, 2000, Society of Biblical Literature, ISBN: 978-1589830264

- Mark S. Smith, The Early History Of God - Yahweh And The Other Deities In Ancient Israel, 2002, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802839725

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- Wyatt, N., Religious Texts from Ugarit: The Words of Ilimilku and His Colleagues, 1998, Continuum International Publishing Group - Sheffie, 2nd edition, ISBN: 978-1850758471

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, 1992, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691036069

- John Day, Yahweh And The Gods And Goddesses Of Canaan, 2002, A&C Black, ISBN: 9780826468307

comments