The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), also known as the Oxus Civilization, represents one of the lesser-known yet significant early civilizations of the Bronze Age. Flourishing between approximately 2300 BCE and 1700 BCE in Central Asia, this civilization was centered in what is now modern-day Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and northern Afghanistan. Known for its rich material culture, advanced urban planning, and long-distance trade networks, the BMAC played a crucial role in connecting the major civilizations of Mesopotamia, India, and the Iranian Plateau.

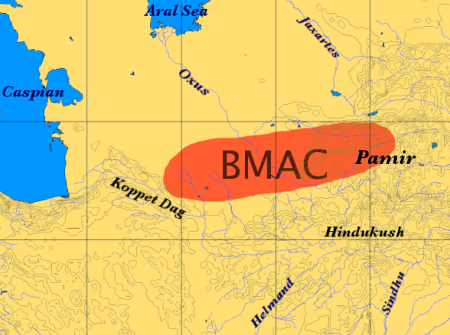

Extent of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), embedded within the broader region of Central Asia, South of the Aral Sea and East of the Caspian Sea. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Geographical foundations and cultural significance

The BMAC developed in the fertile river deltas of the Murghab and Amu Darya rivers, in a region bounded by deserts and mountains. This geography not only provided a stable agricultural base but also facilitated trade and cultural exchange with neighboring regions. The oasis settlements of Gonur Tepe, Togolok, and Dashly were among the prominent centers of the BMAC.

Unlike riverine civilizations such as Mesopotamia and Egypt, the BMAC relied on a network of oases and an intricate irrigation system to sustain its agricultural output. This reliance on dispersed water sources shaped a unique settlement pattern characterized by fortified urban centers surrounded by agricultural hinterlands.

Urbanization and material culture

The BMAC is remarkable for its sophisticated urban planning and material culture. Excavations at Gonur Tepe reveal grid-like layouts, monumental architecture, and advanced water management systems, including canals and reservoirs. Fortifications around many settlements indicate a need for defense, possibly against nomadic incursions.

Bird-headed man with snakes; 2000–1500 BC, bronze, from Northern Afghanistan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Material culture from the BMAC includes finely crafted ceramics, metalwork, and a distinctive array of seals and figurines. The artifacts suggest a complex society with specialized craftspeople and a vibrant trade network. Notably, the seals share stylistic similarities with those of the Indus Valley Civilization, hinting at cultural and commercial interactions.

Religious and ritual practices

The BMAC is also known for its deeply ritualized and symbolic religious practices. Excavations at Gonur Tepe have uncovered temple-like structures featuring altars, water basins, and ritual hearths, indicating a central role for fire and water in their spiritual activities. These findings suggest possible proto-Zoroastrian elements, such as the reverence for fire as a purifying force, which may have later been adapted by the Achaemenid Persians. Burial sites within the complex display a variety of grave goods, including intricately crafted jewelry, ceramics, and metal objects, pointing to beliefs in an afterlife and the importance of accompanying the deceased with valuable items for their journey. The presence of large communal ritual areas and distinctive iconography on seals further highlights the integration of spirituality into both daily and communal life, underscoring the societal cohesion fostered through shared religious traditions.

Left: Female figurine of the “Bactrian princess” type; between 3rd millennium and 2nd millennium BC; chlorite mineral group (dress and headdresses) and limestone (face and neck). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Beaker with birds on the rim; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BCE, electrum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Left: Handled weight, late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BCE, chlorite. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Monstrous male figure, late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BCE, chlorite, calcite, gold and iron. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Trade and connectivity

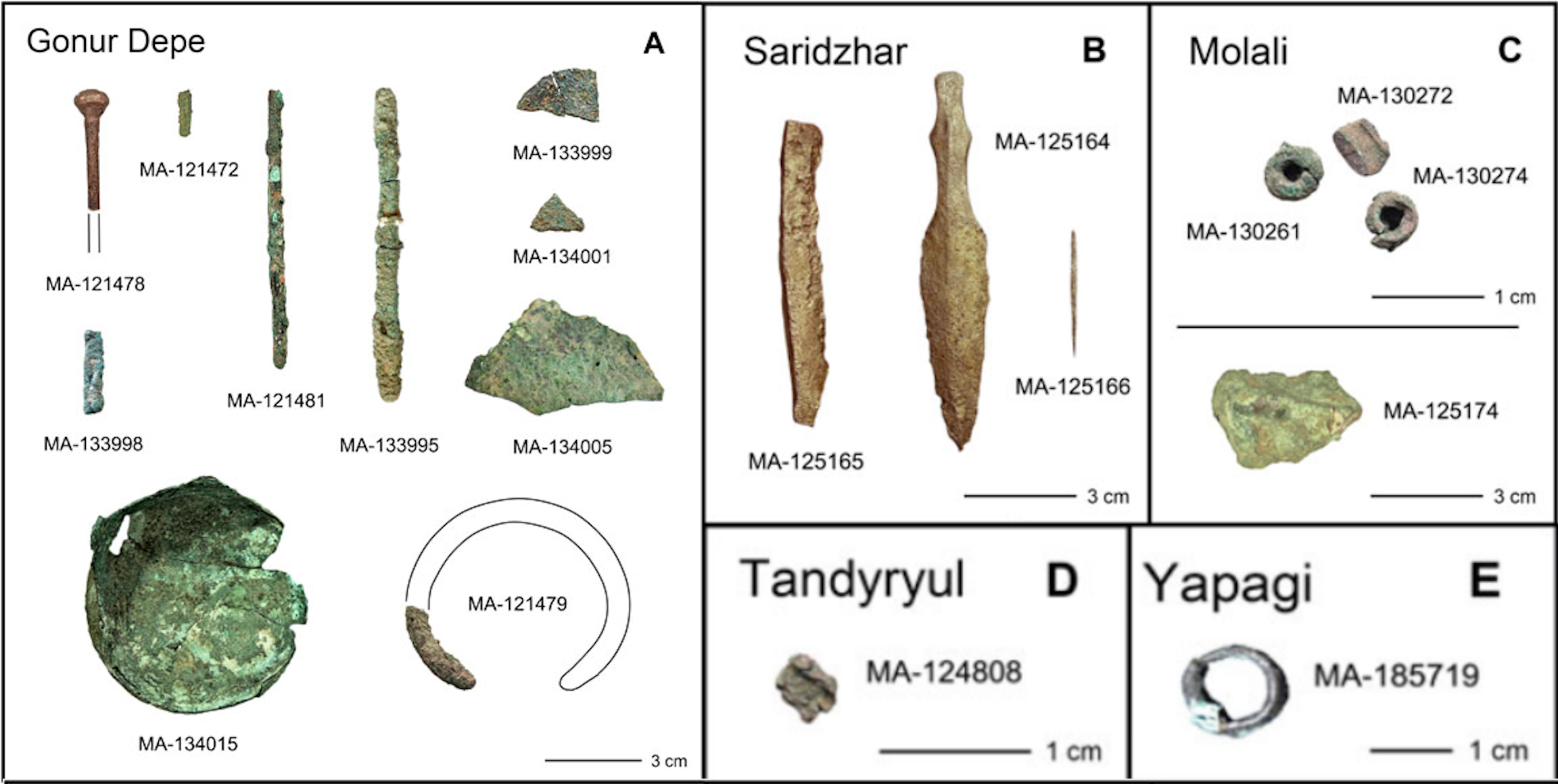

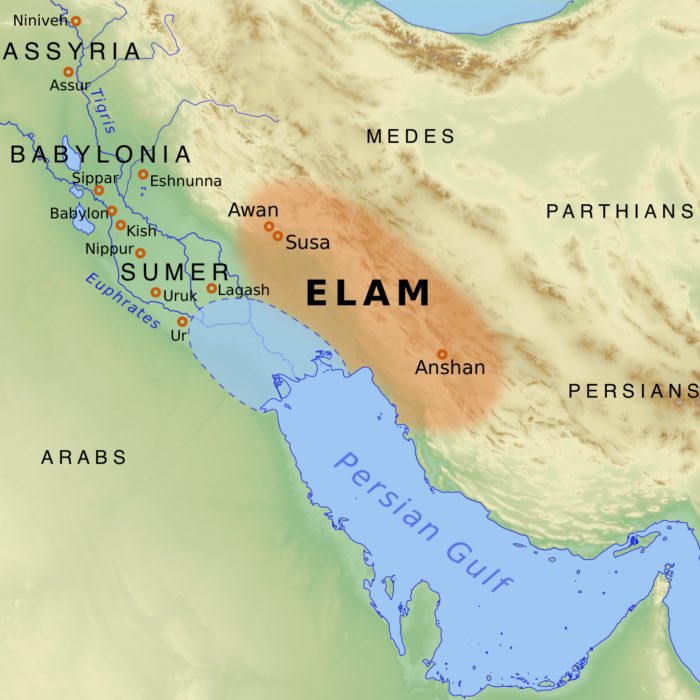

The BMAC occupied a strategic location that made it a crucial hub for trade between Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and the Iranian Plateau, forming a vital link in the complex web of Bronze Age commerce. The discovery of artifacts such as Mesopotamian cylinder seals, Indus beads, and Elamite pottery at BMAC sites underscores its deep integration into a broader network of cultural and economic exchange. This trade was not limited to utilitarian goods but included luxury items that held symbolic and economic significance, such as finely crafted jewelry, carnelian from India, lapis lazuli from Badakhshan, and textiles likely produced locally or imported. These exchanges facilitated the diffusion of technologies, artistic motifs, and possibly even religious ideas, highlighting the BMAC’s role as a dynamic conduit in the ancient world.

BMAC bronze tools. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Comparisons with Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India

The BMAC civilization exhibits intriguing parallels with the major civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India. Like Mesopotamia’s city-states and the urban centers of the Indus Valley, the BMAC featured well-planned cities with advanced infrastructure that reflected an organized and hierarchical society. Its role as a crossroads of commerce, linking distant civilizations, mirrors the extensive trade networks of Egypt with Nubia and Mesopotamia’s connections across the ancient Near East. The fine craftsmanship of BMAC ceramics and seals also echoes the artistic achievements of the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia, underscoring shared aesthetic values and possibly cultural exchanges.

However, the BMAC also stands apart in several key ways. Unlike the riverine civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the BMAC’s survival depended on a network of oases and irrigation systems in an arid environment, highlighting a unique adaptation to its geography. While Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley developed distinct writing systems, the BMAC has no deciphered script associated with its culture, suggesting either a reliance on oral traditions or a writing system yet to be discovered. Additionally, while the monumental architecture of the BMAC is significant, it does not match the scale of Egypt’s pyramids or Mesopotamia’s ziggurats, offering a more modest but equally meaningful architectural legacy.

The BMAC’s interactions with the Indus Valley are particularly noteworthy. Shared motifs on seals and artifacts suggest cultural exchange, while the trade of goods like carnelian and lapis lazuli underscores their economic interdependence. Some scholars debate whether elements of BMAC culture influenced early Vedic traditions in India, with theories suggesting migrations that carried aspects of Central Asian culture into the subcontinent.

Decline and legacy

The BMAC began to decline around 1700 BCE, possibly due to environmental changes, such as the desiccation of rivers, or incursions by nomadic groups. Despite its decline, the cultural and economic contributions of the BMAC influenced subsequent civilizations in Central Asia and beyond. Elements of its material culture and religious practices were absorbed into later empires, including the Achaemenids.

Broader significance

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex highlights the diversity and interconnectedness of early civilizations. While less renowned than Mesopotamia, Egypt, or India, the BMAC played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural and economic landscapes of the ancient world. Its story underscores the importance of regional centers in the broader narrative of human history, demonstrating how even geographically challenging environments could foster advanced societies.

Understanding the BMAC enriches our appreciation of the complexity and interconnectivity of Bronze Age civilizations, reminding us of the shared heritage of human ingenuity and adaptation.

References

- Fredrik Talmage Hiebert, Origins of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia, 1994, Peabody Museum Press, ISBN: 978-0873655453

- Philip L. Kohl, The Making of Bronze Age Eurasia, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521130158

- J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair, The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, 2000, GB Gardners Books, ISBN: 978-0500051016

- Gregory Possehl, The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, 2010, Altamira, ISBN: 978-8178292915

- A. G. Dani and V. M. Masson (Eds.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Dawn of Civilization, 1993, United Nations Educational, ISBN: 978-9231027192

- Andrew Sherratt, Economy and Society in Prehistoric Europe: Changing Perspectives, 1997, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691016979

- Aruz, Joan, Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300098839

- Wikipedia article on the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complexꜛ

comments