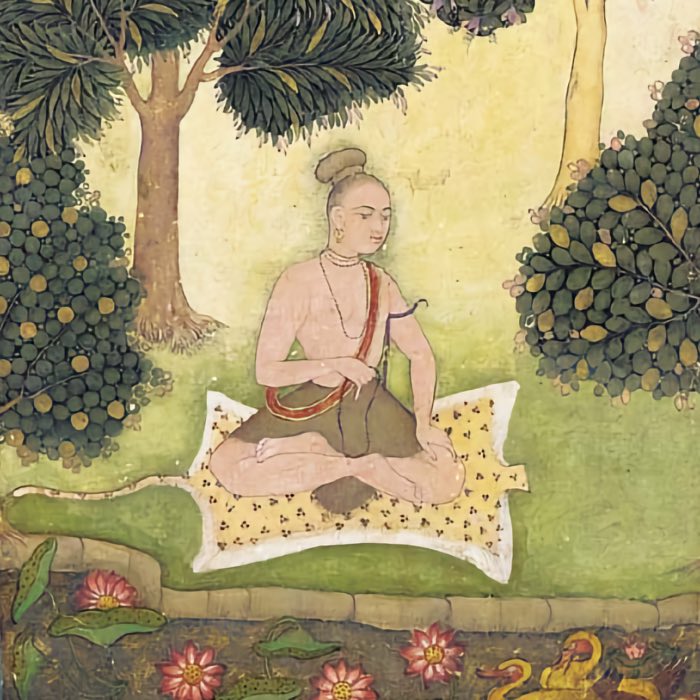

Ātman: The self in Hindu philosophy

The concept of ātman, or the self, is one of the central tenets of Hindu philosophy. Derived from the Sanskrit root “an” (to breathe), ātman originally signified the life-breath or vital essence of a being. Over time, it evolved into a profound metaphysical concept representing the eternal, unchanging self that underlies individual existence. Different schools of Indian philosophy, particularly Vedanta, have offered varied interpretations of ātman, but all agree on its fundamental significance in the quest for liberation (mokṣa). This post explores the origins, philosophical interpretations, and theological importance of ātman in Hindu thought.

The origins of the concept of ātman

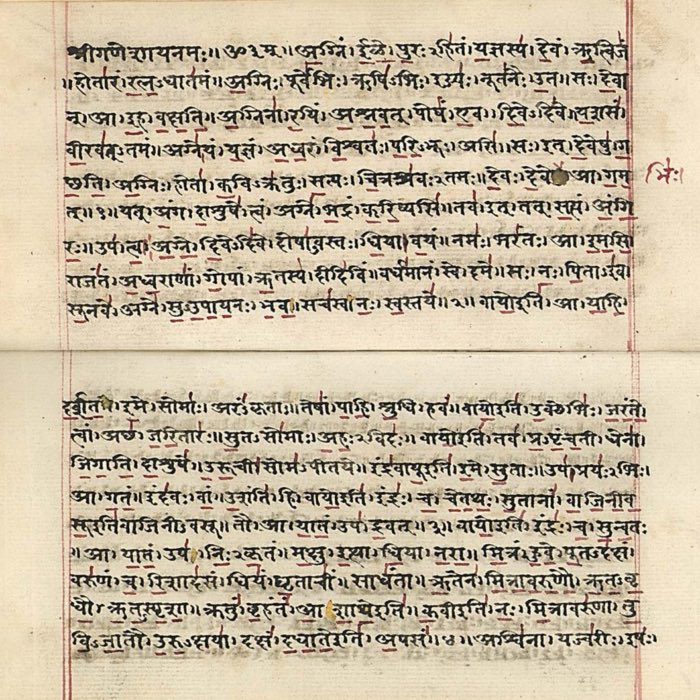

The earliest references to ātman are found in the Vedic texts, where it is associated with breath, life force, and the essence of a person. In the early Vedic period, the focus was primarily on external rituals and sacrifices (yajña) aimed at sustaining cosmic order (ṛta). However, in the later Vedic period, particularly in the Upanishads, the emphasis shifted from external rituals to internal contemplation and the nature of the self.

The Upanishads (circa 800–300 BCE) are the primary sources of philosophical discussions on ātman. They present ātman as the innermost essence of a person, beyond the body, senses, and mind. Several key passages highlight the nature of ātman:

- Chāndogya Upanishad: In the famous teaching “tat tvam asi” (“You are that”), the sage Uddālaka instructs his son Śvetaketu, revealing that ātman is identical to the ultimate reality, brahman.

- Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad: This Upanishad describes ātman as the unchanging witness of all experiences, beyond birth and death.

- Kaṭha Upanishad: It portrays ātman as distinct from the body and senses, emphasizing self-realization as the path to liberation.

Ātman in the schools of Vedanta

Vedanta, which is primarily based on the teachings of the Upanishads, developed extensive philosophical interpretations of ātman. The major schools of Vedanta—Advaita, Viśiṣṭādvaita, and Dvaita—offer distinct perspectives on the relationship between ātman and brahman.

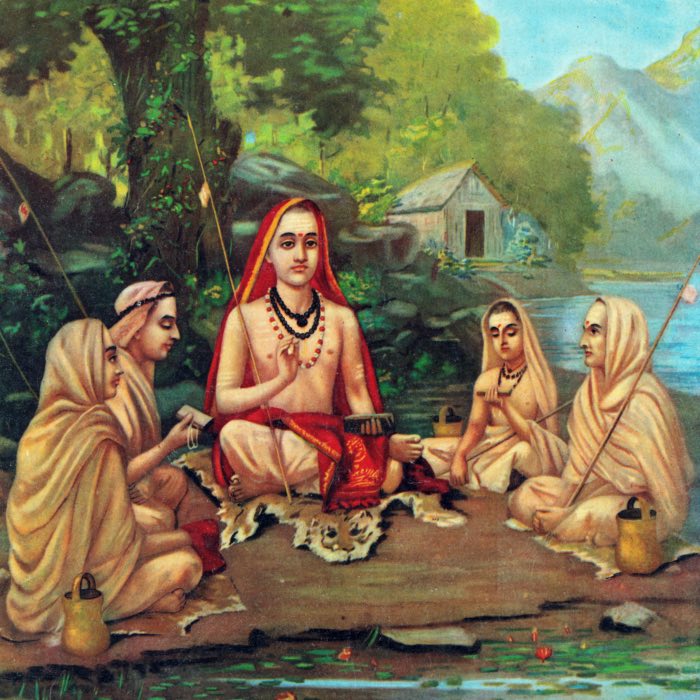

Advaita Vedanta: Non-dualism

In Advaita Vedanta, as formulated by Ādi Śankara, ātman and brahman are considered identical. According to this school:

- Ātman is the only reality: The individual self, when stripped of ignorance (avidyā) and false identification with the body and mind, is realized to be none other than brahman.

- Illusory individuality: The perception of distinct individual selves is a result of ignorance. Liberation (mokṣa) involves the realization of the non-duality (advaita) of ātman and brahman.

- Jñāna (knowledge) as the path: Self-inquiry (ātma-vicāra) and knowledge of one’s true nature lead to liberation.

Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta: Qualified non-dualism

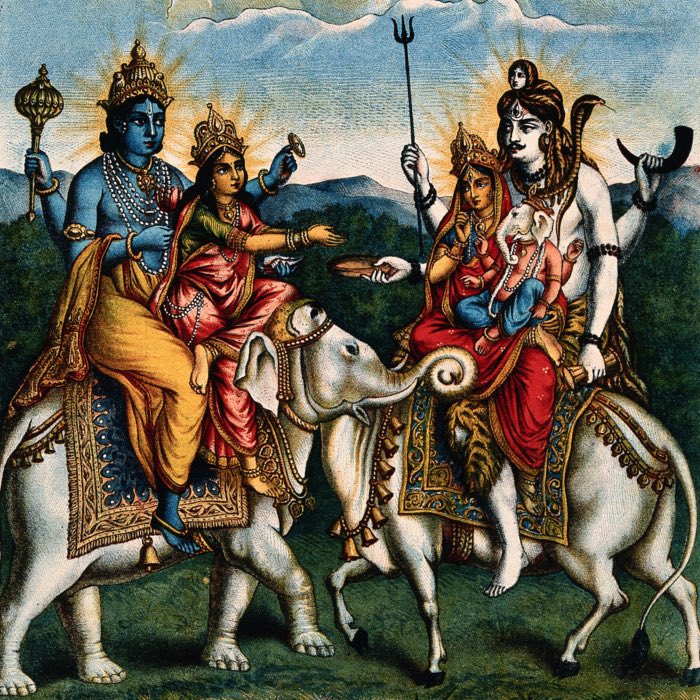

Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta, established by Rāmānuja, posits that while ātman and brahman are distinct, they are inseparably related. Key points include:

- Ātman as a mode of brahman: Individual selves are real but dependent on brahman, who is identified with the personal God Viṣṇu.

- Unity in diversity: While there are many individual selves, they are all united in their dependence on and relationship with brahman.

- Bhakti (devotion) as the path: Liberation involves realizing one’s eternal dependence on brahman and engaging in loving devotion to Him.

Dvaita Vedanta: Dualism

In Dvaita Vedanta, founded by Madhva, ātman and brahman are entirely distinct. According to this dualistic school:

- Ātman is eternally distinct from brahman: Each individual self is unique and separate from brahman, who is identified with Viṣṇu.

- Dependence on divine grace: Liberation is achieved through devotion to brahman (Viṣṇu) and reliance on His grace.

- Multiplicity of selves: Unlike Advaita, which holds that individuality is illusory, Dvaita asserts that individuality is real and eternal.

Ātman in Sāṁkhya and Yoga

Outside Vedanta, other Indian philosophical schools also developed nuanced views on ātman:

- Sāṁkhya: In Sāṁkhya philosophy, puruṣa (pure consciousness) corresponds to ātman. Each individual puruṣa is distinct, eternal, and unchanging. Liberation involves realizing the distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti (matter).

- Yoga: Patañjali’s Yoga philosophy, closely related to Sāṁkhya, emphasizes the realization of puruṣa through disciplined practice (sādhana), including meditation (dhyāna) and self-control (niyama).

Ātman and the cycle of samsāra

In Hindu philosophy, ātman is believed to be subject to the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra) due to the accumulation of karma. Liberation (mokṣa) is the cessation of this cycle, achieved by realizing the true nature of ātman as distinct from the body and mind. Different schools propose various means to attain this realization:

- Advaita Vedanta: Knowledge of non-duality (jñāna yoga).

- Viśiṣṭādvaita and Dvaita Vedanta: Devotion and surrender (bhakti yoga).

- Sāṁkhya and Yoga: Discrimination between self and matter, combined with meditative absorption (samādhi).

Conclusion

The concept of ātman lies at the heart of Hindu philosophical and spiritual traditions. Whether viewed as identical to brahman or as distinct from it, ātman represents the eternal essence of an individual, transcending physical existence. The philosophical inquiry into the nature of ātman shaped not only the development of Vedantic thought but also influenced other major schools like Sāṁkhya and Yoga. Its examination across diverse schools highlights the intellectual dynamism of ancient Indian philosophy, which engaged rigorously with questions of existence, consciousness, and liberation (mokṣa).

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- Paul Deussen, The philosophy of the Upanishads, 2010, Cosimo Classics, ISBN: 978-1616402402

- Eliot Deutsch, Advaita Vedanta: A philosophical reconstruction, 1969, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824802714

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

comments