The adaptability and integrative ability of Buddhism

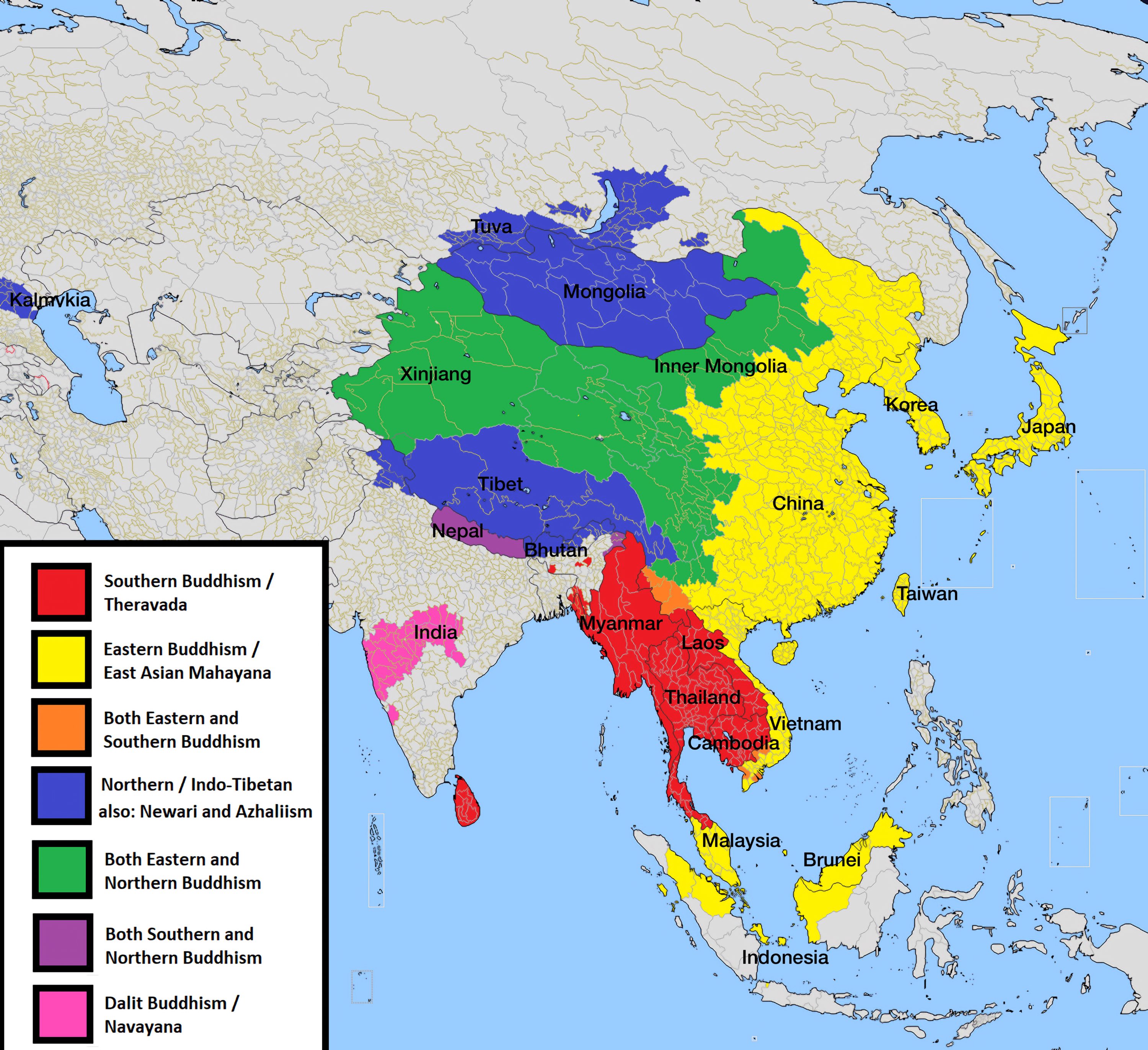

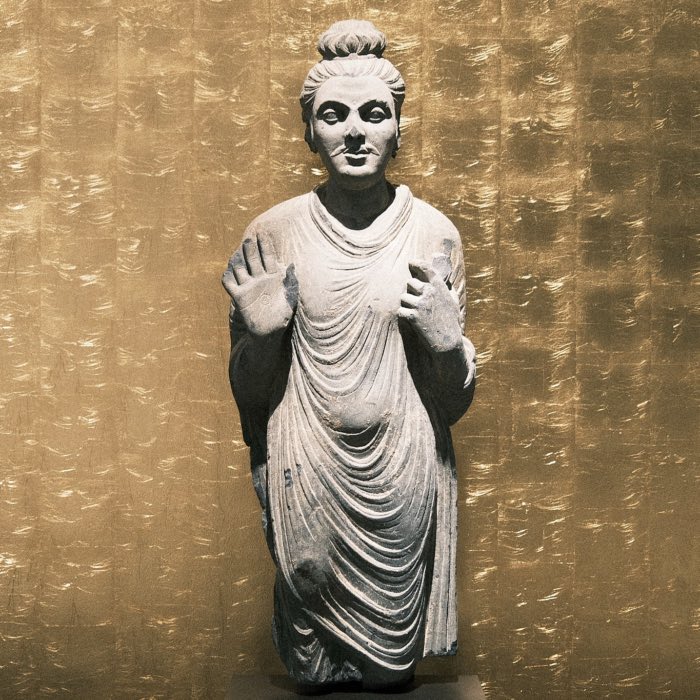

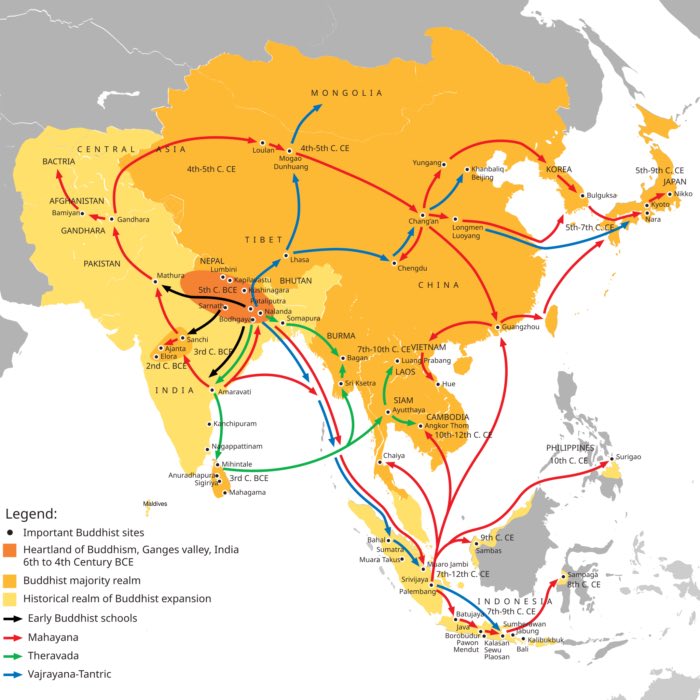

Buddhism, from its inception in the 5th–6th century BCE under the teachings of Gautama Buddha, has displayed remarkable adaptability, integrating and assimilating local traditions, beliefs, and deities as it spread across Asia. While Buddhism fundamentally centers on the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path as means to end suffering and attain liberation (nirvāṇa), it did not rigidly impose a monolithic doctrine in the regions it reached. Instead, it evolved by accommodating existing religious systems, thereby enhancing its appeal to diverse populations while maintaining its core philosophical tenets.

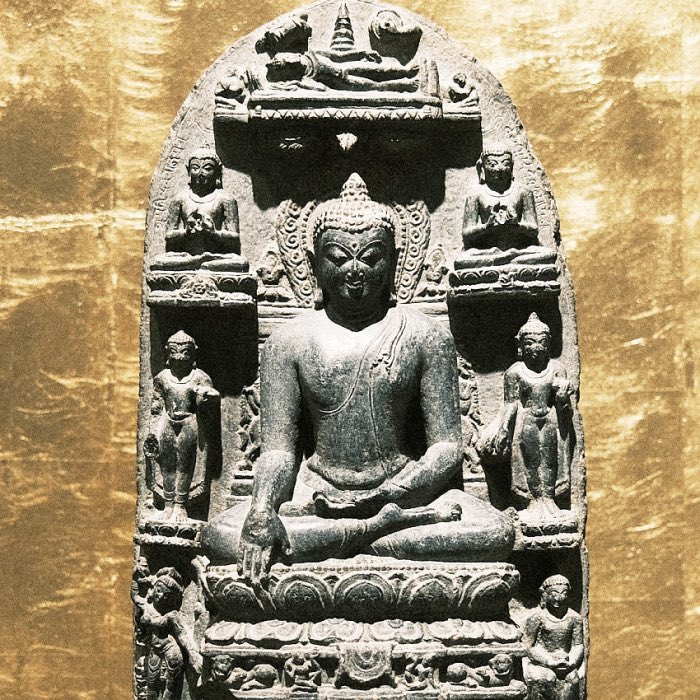

Six-armed Mahakala, a wrathful deity in Vajrayana Buddhism, Tibet, 17th century. Mahakala is one of the so-called Dharmapalas, or protectors of the Buddhist teachings. They are often depicted as fierce beings who guard against obstacles to spiritual practice. While Dharmapalas were not part of the original Buddhist core teachings, they were integrated into the tradition as it spread to Tibet and other regions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The integrative capacity of Buddhism is best exemplified in its interaction with Hindu deities, its incorporation of Tibetan indigenous beliefs, and its syncretism in regions such as China and Japan. In this post, we shed some light on how Buddhism’s adaptability has been a key factor in its spread and impact on diverse cultures.

The integration of Hindu deities and philosophical concepts

When Buddhism emerged in ancient India, it did so within the intellectual and cultural milieu of Hinduism (then known as Vedic religion). While early Buddhist teachings rejected the authority of the Vedas and the concept of an eternal ātman (self), they did not entirely discard the existing pantheon of Hindu gods. Instead, these deities were reinterpreted within a Buddhist framework.

In the Pali Canon and other early texts, Hindu deities such as Indra, Brahmā, and Viṣṇu are frequently mentioned. However, unlike in Hinduism, these deities are not seen as ultimate or omnipotent but are regarded as beings subject to the same cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra) as humans. For example, Brahmā is depicted in some texts as a deity who mistakenly believes himself to be eternal and omniscient, only to be corrected by the Buddha. This reinterpretation allowed Buddhism to coexist with prevailing religious beliefs without directly challenging the popular devotion to these deities.

Later Mahayana texts, particularly those of the Tantric tradition, integrated Hindu gods more fully into Buddhist cosmology. Deities such as Śiva and Viṣṇu were absorbed as protectors or emanations of enlightened wisdom. For example, in the esoteric traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism, Mahākāla, originally a form of Śiva in Hinduism, became a wrathful protector deity (dharmapāla) guarding Buddhist teachings. This syncretism enabled Buddhism to appeal to followers who retained their devotion to traditional gods while adopting Buddhist philosophical practices.

The assimilation of Tibetan indigenous beliefs and deities

The spread of Buddhism into Tibet in the 7th century CE under the patronage of King Songtsen Gampo marked another significant instance of cultural integration. Prior to the introduction of Buddhism, Tibet had a rich indigenous religious tradition known as Bön, characterized by shamanistic practices, nature worship, and a pantheon of local deities and spirits. Rather than eradicating these beliefs, Buddhism in Tibet adapted by incorporating many aspects of Bön into its rituals and cosmology.

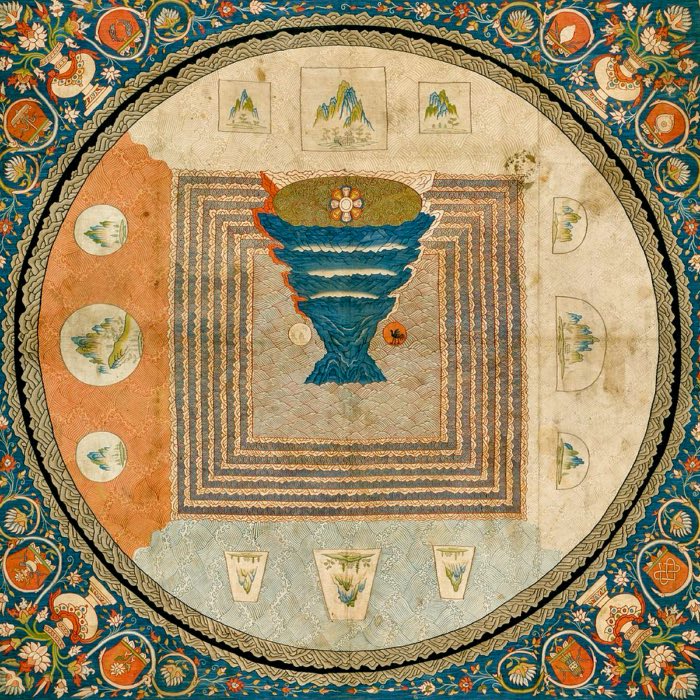

Tibetan Buddhism, particularly in its Vajrayana form, retained the use of mantras, mandalas, and mudras — practices that had parallels in Bön ritualistic traditions. Additionally, many Bön deities and spirits were integrated into the Buddhist pantheon as protectors or guardians of the Dharma. For example, Pehar, a powerful spirit in Bön, became a key guardian deity in Tibetan Buddhism, associated with the Nechung Oracle, an important institution in Tibetan governance and religious life.

Furthermore, the Tibetan Buddhist concept of terma (hidden spiritual treasures) reflects the influence of indigenous beliefs. Termas are texts or objects said to have been hidden by enlightened beings and later discovered by tertöns (treasure revealers). This idea of hidden wisdom aligns closely with pre-Buddhist Tibetan notions of sacred relics and hidden knowledge.

The synthesis of Bön and Buddhism led to a unique form of Vajrayana that preserved Tibetan cultural identity while incorporating the philosophical depth and meditative practices of Indian Buddhism. This integrative approach not only facilitated the acceptance of Buddhism in Tibet but also enriched its ritualistic and cosmological dimensions.

Adaptability in East Asia: The case of China and Japan

Buddhism’s adaptability is further evident in its spread to China and Japan, where it encountered well-established religious traditions such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Shinto. In China, Buddhism initially faced resistance due to its foreign origin and perceived incompatibility with Confucian ideals of social order. However, by adapting its teachings to emphasize filial piety and ethical conduct — values central to Confucianism — Buddhism gradually gained acceptance.

Moreover, Chinese Buddhism integrated Daoist terminology and concepts. For instance, the translation of Buddhist texts into Chinese often employed Daoist terms to convey complex ideas. The concept of nirvāṇa was sometimes translated using the Daoist notion of wu wei (non-action), creating parallels between the two traditions. Over time, this syncretism gave rise to uniquely Chinese schools of Buddhism, such as Chan (known as Zen in Japan), which emphasized direct experience and meditation, akin to Daoist introspection.

In Japan, Buddhism coexisted with Shinto, the indigenous religion centered on kami (spirits or deities). Rather than displacing Shinto, Buddhism assimilated many Shinto practices and deities. The doctrine of honji suijaku emerged, which held that Shinto deities were manifestations of Buddhist principles. This allowed for the harmonious coexistence of the two traditions, with many Japanese temples housing both Buddhist and Shinto shrines.

Adaptation in Southeast Asia: The case of Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos

Buddhism’s spread to Southeast Asia offers another compelling example of its adaptability. Theravāda Buddhism, introduced primarily through Sri Lankan influence around the 3rd century BCE, became the dominant form of Buddhism in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. Over time, local traditions and animistic beliefs were incorporated into Buddhist practice, resulting in a distinct regional expression of the faith.

Thailand: Integration with animist and Brahmanical practices

In Thailand, Buddhism integrated with pre-existing animist and Brahmanical practices. Local deities and spirits were woven into the Buddhist cosmology as protective figures or guardian spirits, and rituals involving offerings to these spirits became commonplace. The Thai Buddhist monastic tradition, with its emphasis on meditation and adherence to the Vinaya (monastic code), coexists with popular devotional practices aimed at gaining merit (puńŋya) through acts of generosity and temple worship.

Cambodia: A blend of Hindu-Buddhist heritage

Cambodia’s Buddhist landscape reflects centuries of cultural exchange and adaptation. Initially influenced by both Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism during the Angkor period (9th to 15th centuries CE), Theravāda Buddhism gradually became dominant. Today, Cambodian Buddhism incorporates elements of its earlier Hindu-Buddhist heritage, evident in its art, architecture, and rituals.

Laos: Syncretism of Theravāda Buddhism and spirit worship

In Laos, the integration of local animist traditions resulted in a unique blend of Theravāda Buddhism and spirit worship. The spread of Buddhism in Laos was closely linked to the establishment of the Lan Xang Kingdom in the 14th century, influenced by Sri Lankan and Thai monastic communities. Lao Buddhism incorporates pre-Buddhist animist practices, particularly the veneration of spirits known as phi. Ceremonies such as the baci ritual, which involves tying strings around the wrists to ensure well-being and preserve spiritual harmony, illustrate how indigenous customs were incorporated into the Buddhist framework. Monasteries in Laos continue to serve as centers of education and community gatherings, highlighting the enduring social role of Buddhism.

Vietnam: Syncretism with Confucianism and Daoism

In Vietnam, Buddhism first arrived via the Silk Road and maritime trade routes around the 2nd century CE. Initially influenced by Mahayana schools from China, Vietnamese Buddhism developed a unique character by incorporating elements of Confucianism and Daoism. The Trúc Lâm school of Zen Buddhism, established during the Tran dynasty in the 13th century, exemplifies this syncretic approach. Vietnamese Buddhist temples often house altars dedicated to Buddhist, Confucian, and Daoist deities, reflecting the integration of these traditions into everyday religious practice. Ancestor worship, a key aspect of Vietnamese culture, also became intertwined with Buddhist rituals, demonstrating the adaptability of the religion in addressing local customs and familial obligations.

Myanmar: Patronage and indigenous nat worship

In Myanmar (formerly Burma), Buddhism was introduced as early as the 3rd century BCE, during the reign of Emperor Ashoka, who sent missionaries to the region. Over time, Theravāda Buddhism became the predominant form, deeply influencing Burmese culture, politics, and daily life. Burmese kings, particularly during the Bagan Empire (11th–13th centuries), patronized Buddhism by constructing monumental stupas and temples, such as the iconic Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon. Burmese Buddhism incorporates indigenous nat worship, where spirits are believed to inhabit natural objects and landscapes. These spirits are often propitiated alongside traditional Buddhist practices, creating a syncretic religious landscape.

Philosophical implications of Buddhist adaptability

The adaptability of Buddhism raises important philosophical questions about the nature of religious identity and doctrinal purity. Unlike many religions that seek to establish exclusive truth claims, Buddhism’s approach has been one of pragmatic inclusivity. By adopting local beliefs and practices, Buddhism was able to remain relevant across vastly different cultural contexts without compromising its core teachings on suffering, impermanence (anicca), and non-self (anatta).

This adaptability also reflects the Buddhist emphasis on skillful means (upāya-kauśalya), a concept found in Mahayana texts, which advocates the use of whatever methods are most effective in guiding beings toward liberation. The incorporation of local deities, rituals, and cosmologies can thus be seen as a form of upāya, ensuring that the teachings resonate with diverse audiences while ultimately leading them toward the same goal of enlightenment.

Conclusion

Buddhism’s remarkable adaptability and integrative ability have been key to its survival and expansion over millennia. By engaging with and incorporating local religious traditions, whether through the reinterpretation of Hindu gods, the assimilation of Tibetan beliefs, or the syncretism with East Asian philosophies, Buddhism has continually evolved while retaining its core principles. This integrative approach not only facilitated its spread but also enriched its philosophical and cultural heritage, making it one of the most enduring and influential spiritual traditions in the world.

Spread of Buddhism and its schools in East Asia (modified). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Gethin, R., The Foundations of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192892232

- Johannes Bronkhorst, Greater Magadha: Studies in the culture of early India, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359663975

- Edward Conze, Buddhist thought in India: Three phases of Buddhist philosophy, 1967, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0472061297

- Samuel, G. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies, 1995, Smithsonian Institution Press, ISBN: 978-1560986201

- Lopez, D. S. The Story of Buddhism: A Concise Guide to Its History and Teachings, 2002, HarperOne, ISBN: 978-0060099275

- Snellgrove, D. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors, 2019, Orchid Press Publishing Limited, ISBN: 978-9745242128

- Anthony Reid, A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads, 2015, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1118513002

- Skilling, Peter, Buddhism and Buddhist Literature of South-East Asia Selected Papers, 2009, Fragile Palm Leaves Foundation, ISBN: 978-974-660-104-7

- Swearer, Donald K., The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia, 2010, SUNY Press, ISBN: 9781438432519

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja,Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in Northeast Thailand, 1970, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521078252

- Alexandra Green, Burma To Myanmar, 2023, British Museum Press, ISBN: 9780714124957

comments