Uruk: The first mega-city of humanity

Uruk, a city located in the fertile plains of southern Mesopotamia, stands as a monumental milestone in human history. Emerging during the Uruk period (ca. 4000–3100 BCE), it represents humanity’s first known urban center and a transformative moment in the evolution of societal complexity. Uruk’s unprecedented scale, technological advancements, and cultural achievements earned it the title of the world’s first “mega-city”. Its legacy reverberates through subsequent civilizations, shaping the trajectory of urban development, statecraft, and cultural production.

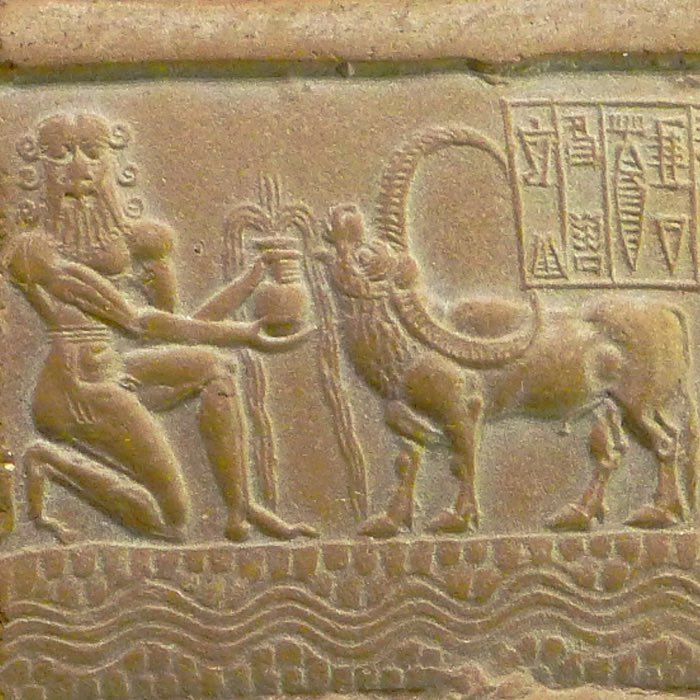

Devotional scene to Inanna, Warka Vase, c. 3200–3000 BCE, Uruk. This is one of the earliest surviving works of narrative relief sculpture. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Geographical and environmental foundations

Uruk’s location was no accident. Situated near the Euphrates River in what is now modern-day Iraq, Uruk occupied a strategic position within the fertile alluvial plains of Mesopotamia. The region’s rich soil, replenished annually by the river’s floods, supported intensive agriculture, enabling the production of surpluses necessary for large, sedentary populations. However, managing this environment also required sophisticated irrigation systems to channel water to fields and protect settlements from flooding.

Left: Map of Sumer (5500-1800 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Sumer and its major cities. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The construction of canals and reservoirs reflects Uruk’s mastery of environmental engineering. These waterworks not only ensured agricultural stability but also supported economic activities such as pottery production, textile manufacturing, and trade, laying the groundwork for the city’s explosive growth.

The scale of urbanization

Uruk’s population and physical size marked a stark departure from earlier settlements. By around 3100 BCE, it is estimated to have housed 40,000–80,000 residents, an unprecedented concentration of people for its time. Covering approximately 6 square kilometers at its peak, the city featured densely packed residential neighborhoods, administrative complexes, and monumental architecture, representing a complexity unparalleled in earlier human societies.

The core of Uruk was its two great temple precincts: the Eanna District, dedicated to the goddess Inanna (Ishtar), and the Anu District, named for the sky god Anu. These centers were not merely religious; they served as hubs of administration and economic activity, illustrating the deeply interconnected roles of religion, governance, and economics in early urban life.

Floor plans of Uruk, Eanna district. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The construction of monumental structures such as the White Temple, a shining ziggurat that towered above the Anu District, required unprecedented levels of organization, labor mobilization, and resource allocation. These achievements underscore Uruk’s status as a political and cultural powerhouse.

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the ‘Anu Ziggurat’, dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BCE. The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BC. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0); Bottom source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the ‘Anu Ziggurat’, dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BCE. The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BC. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0); Bottom source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Economic and technological innovations

Uruk’s urbanization was closely tied to its economic and technological dynamism. The surplus agricultural production of the surrounding countryside fueled not only population growth but also economic specialization. Artisans produced goods ranging from finely crafted pottery to textiles, while merchants facilitated trade with regions as distant as the Indus Valley, Anatolia, and the Arabian Peninsula.

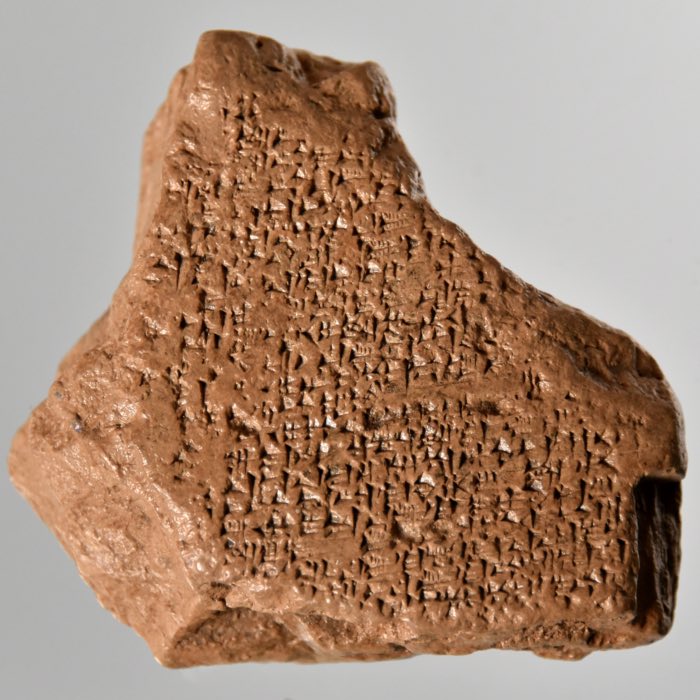

The city was also a pioneer in administrative technology. The invention of writing, specifically proto-cuneiform, is one of Uruk’s most enduring legacies. Originally developed to manage economic transactions, such as the distribution of grain or the allocation of labor, writing quickly evolved into a tool for recording laws, religious rituals, and cultural narratives. Clay tablets uncovered in Uruk’s ruins provide valuable insights into the city’s sophisticated bureaucracy and societal organization.

Proto-cuneiform lexical list of places. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another significant innovation attributed to Uruk is the mass production of pottery. The advent of the fast potter’s wheel allowed for the efficient creation of standardized ceramic vessels, a development that reflects both the technological ingenuity and economic scale of the city.

Religion and cultural achievements

Religion was central to Uruk’s identity, and the city’s grandeur was inextricably linked to its devotion to the gods. The temples of the Eanna and Anu districts were not only architectural marvels but also spiritual centers where priests mediated between the divine and the human. These temples accumulated wealth, controlled vast tracts of land, and played a pivotal role in the redistribution of resources.

Clay impression of a cylinder seal with monstrous lions and lion-headed eagles, Mesopotamia, Uruk Period (4100 BC–3000 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: Foundation peg of Lugal-kisal-si, king of Uruk, Ur and Kish, circa 2380 BCE. The inscription reads ‘For (goddess) Namma, wife of (the god) An, Lugalkisalsi, King of Uruk, King of Ur, erected this temple of Namma’. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Male deity pouring a life-giving water from a vessel. Facade of Inanna Temple at Uruk, 15th century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The goddess Inanna held a particularly prominent place in Uruk’s religious life. Often depicted as the goddess of love, war, and fertility, Inanna’s worship reflected the complexities of urban life, embodying both its generative and destructive forces. The myths associated with her, including the Descent of Inanna, offer profound insights into early Mesopotamian cosmology and the societal values of the time.

Left: Goddess Ishtar on an Akkadian Empire seal, 2350–2150 BCE. She is equipped with weapons on her back, has a horned helmet, places her foot in a dominant posture upon a lion secured by a leash and is accompanied by the star of Shamash. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Inanna receiving offerings on the Uruk Vase, circa 3200–3000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Uruk’s literary and artistic achievements extended beyond religion. The city is credited with the creation of some of the earliest known forms of narrative art, as evidenced by cylinder seals and carved reliefs. These artifacts not only document aspects of daily life but also reveal the symbolic and ideological underpinnings of Uruk society.

The role of trade and interaction

Uruk’s growth and influence extended far beyond its immediate environs. Archaeological evidence points to the existence of the Uruk Expansion, a period during which Uruk-style artifacts, architecture, and cultural practices appeared in distant regions such as northern Mesopotamia, Iran, and Anatolia. This diffusion suggests that Uruk established a network of trade and cultural exchange that connected disparate communities, spreading its innovations across a wide geographical area.

Tablet from Uruk III (c. 3200–3000 BC) recording beer distributions from the storerooms of an institution. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Tablet from Uruk III (c. 3200–3000 BC) recording beer distributions from the storerooms of an institution. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Uruk’s dominance as a center of trade and culture made it a focal point for the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies. The presence of lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, copper from Anatolia, and other exotic materials in Uruk underscores the city’s far-reaching connections and its role as a hub in an increasingly interconnected ancient world.

Decline and legacy of Uruk

Uruk’s influence waned after the rise of competing city-states and empires, such as Akkad and Babylon. By the early second millennium BCE, its political and economic significance had diminished, though it continued to function as a religious center for centuries.

Despite its decline, Uruk’s legacy endured. Its innovations in writing, urban planning, and statecraft shaped the civilizations that followed, from the Akkadians to the Babylonians and beyond. The myths and cultural practices born in Uruk left an indelible mark on Mesopotamian culture and resonate in the broader history of human civilization.

Conclusion

Uruk stands as an example for humanity’s capacity for innovation and organization. As the first mega-city, it pioneered the social, economic, and technological frameworks that underpin urban life to this day. Its achievements in writing, architecture, and trade reflect not only the ingenuity of its inhabitants but also the transformative potential of collective human effort. By studying Uruk, we gain not only a deeper understanding of ancient Mesopotamia but also insights into the origins of the complex societies that define our modern world.

References and further reading

- Nicola Crüsemann, Uruk - 5000 Jahre Megacity, 2013, Imhof, Petersberg, ISBN: 9783865688446,

- Pollock, S., Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden That Never Was, 1999, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521575683

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC, 2024, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 9781394210220

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521533386

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, The Sumerian World, 2013, Routledge, ISBN: 9780415569675

- Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia - The invention of the city, 2001, Allan Lane, ISBN: 9780713991987

- Roaf, M., Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, 1990, Facts on File, ISBN: 978-0816022182

- Wikipedia article on Urukꜛ

comments