The Sumerians: The first civilization

The Sumerians, inhabitants of the fertile plains of southern Mesopotamia, are credited with laying the foundation for what is commonly regarded as the world’s first civilization. Flourishing between approximately 4500 and 1900 BCE, their culture, innovations, and societal organization shaped not only their immediate environment but also the trajectory of human history. As pioneers of urbanization, writing, and organized religion, the Sumerians set the stage for subsequent Mesopotamian civilizations and left an indelible mark on the ancient Near East.

Enthroned Sumerian king of Ur, possibly Ur-Pabilsag, with attendants. Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Enthroned Sumerian king of Ur, possibly Ur-Pabilsag, with attendants. Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Geographic and environmental foundations

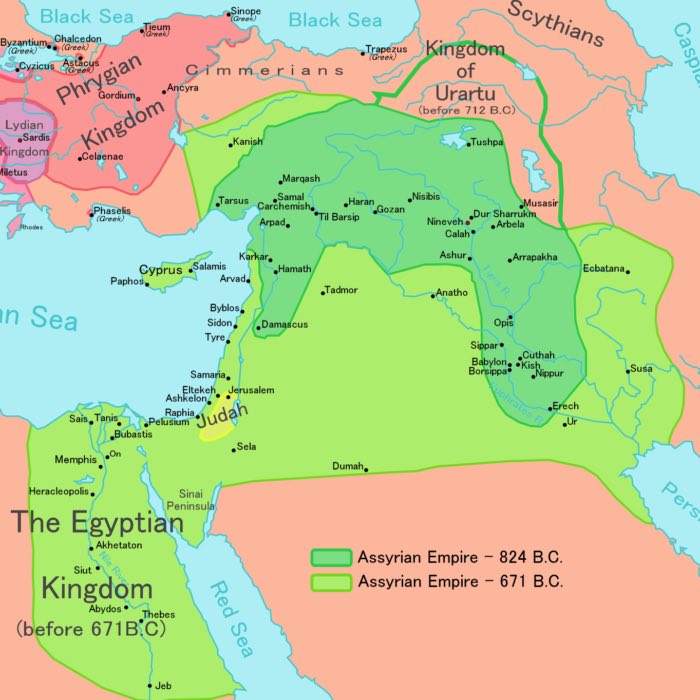

The Sumerian heartland, situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, was marked by a challenging environment. While the rivers provided fertile alluvial soil, essential for agriculture, they were also prone to unpredictable flooding. This duality fostered a necessity for large-scale cooperative efforts to manage irrigation and flood control, leading to the emergence of complex societal structures. Unlike northern Mesopotamia, where rainfall supported agriculture, the arid southern plains demanded technological ingenuity. Sumerians responded with the construction of canals, levees, and reservoirs, creating a landscape capable of sustaining dense populations and abundant agricultural surplus.

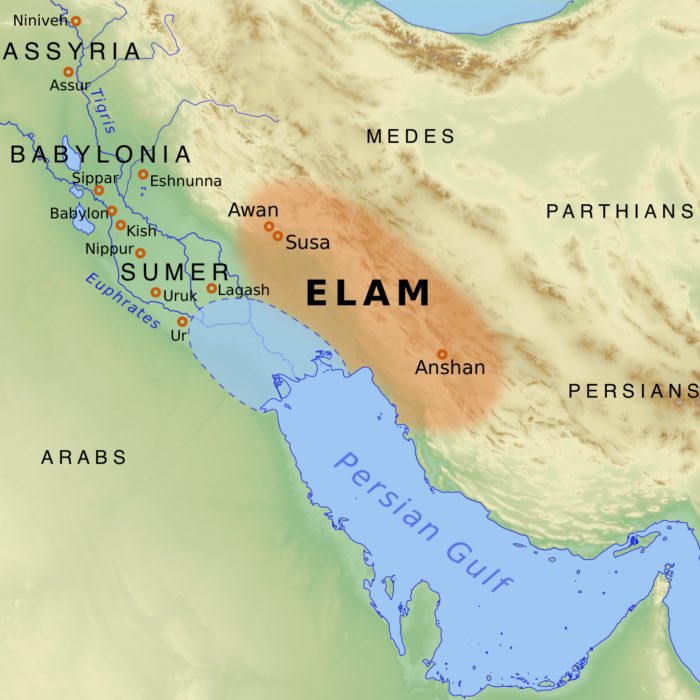

Left: Map of Sumer (5500-1800 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Sumer and its major cities. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

This environmental mastery facilitated the growth of city-states, each functioning as a politically independent yet culturally interconnected entity. Notable cities included Uruk, Ur, Lagash, and Eridu, each characterized by monumental architecture, organized governance, and distinct economic and religious institutions.

Sociopolitical organization and urbanization

The Sumerians are often credited with the invention of the city-state, a form of sociopolitical organization in which a city and its surrounding hinterland operated as a self-contained political unit. These city-states were ruled by a priest-king, known as the ensi or lugal, who held dual roles as a religious leader and a secular authority. Governance revolved around the temples, which were both religious and administrative centers.

Left: A portrait of Ur-Ningirsu, son of Gudea, c. 2100 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Gudea of Lagash, the Sumerian ruler who was famous for his numerous portrait sculptures that have been recovered. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Uruk, often regarded as the world’s first true city, exemplifies the zenith of Sumerian urbanization. By 3100 BCE, it had grown to a population of approximately 40,000, featuring monumental structures such as the White Temple, dedicated to the sky god Anu, and the Eanna precinct, devoted to the goddess Inanna. These buildings not only served religious purposes but also symbolized the city’s political and economic power.

Economic specialization emerged as a hallmark of Sumerian society. Farmers, artisans, merchants, and administrators engaged in a proto-capitalist economy, with trade extending beyond Mesopotamia to regions as distant as the Indus Valley, Anatolia, and the Arabian Peninsula. The Sumerians’ development of long-distance trade networks underscores their role as cultural and economic intermediaries in the ancient world.

Trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus would have been significantly shorter due to lower sea levels in the 3rd millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Writing and administration

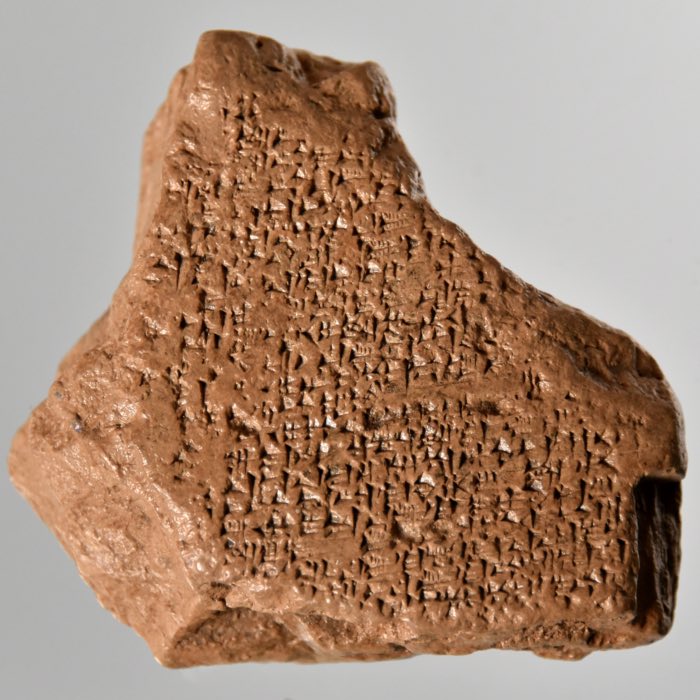

The Sumerians are perhaps most renowned for their invention of writing, a transformative development that emerged around 3100 BCE. Initially devised as a practical tool for record-keeping in trade and administration, writing evolved into a medium for literature, law, and religious expression. The earliest Sumerian script, known as proto-cuneiform, consisted of pictographs etched into clay tablets. Over time, this system became more abstract and phonetic, culminating in the fully developed cuneiform script.

A bill of sale of a field and a house, from Shuruppak, c. 2600 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

A bill of sale of a field and a house, from Shuruppak, c. 2600 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Writing revolutionized Sumerian administration by enabling the codification of laws, the standardization of economic transactions, and the preservation of knowledge. Texts such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, one of the earliest known legal codes, illustrate the sophisticated legal and moral frameworks of Sumerian society. Beyond practicality, writing also facilitated the creation of enduring literary works, most famously the Epic of Gilgamesh, which explores themes of mortality, friendship, and human ambition.

An account of barley rations issued monthly to adults and children written in cuneiform script on a clay tablet, written in year 4 of King Urukagina, c. 2350 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Religion and mythology

Religion permeated every aspect of Sumerian life, providing both a cosmological framework and a justification for political authority. The Sumerians worshipped a pantheon of anthropomorphic deities, each associated with natural forces or societal functions. Anu, Enlil, and Enki, among others, occupied the upper echelons of the divine hierarchy, while local gods held sway in individual city-states. For example, Inanna, the goddess of love and war, was particularly venerated in Uruk.

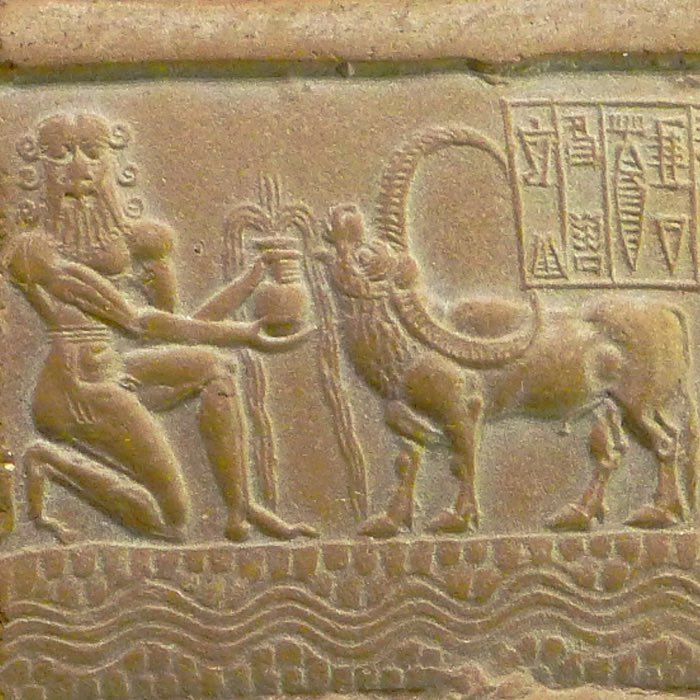

Wall plaque showing libations to a seated god and a temple. Ur, 2500 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Wall plaque showing libations to a seated god and a temple. Ur, 2500 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sumerian mythology reflects their attempts to understand and control their environment. Myths such as the Enuma Elish and tales of divine-human interaction underscore themes of creation, divine retribution, and the precarious balance between order and chaos. Temples, or ziggurats, served as physical and spiritual centers, symbolizing the connection between the earthly and the divine.

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the ‘Anu Ziggurat’, dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BCE. The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BC. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0); Bottom source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the ‘Anu Ziggurat’, dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BCE. The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BC. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0); Bottom source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Religious rituals, festivals, and offerings were integral to maintaining the favor of the gods, who were believed to directly influence natural and societal outcomes. This belief system fostered a worldview that emphasized human dependence on divine will, reinforcing the authority of temple institutions and their leaders.

Akkadian cylinder seal from sometime around 2300 BC or thereabouts depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, Enki, and Isimud. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Akkadian cylinder seal from sometime around 2300 BC or thereabouts depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, Enki, and Isimud. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Technological and cultural achievements

The Sumerians were innovators in multiple domains. In addition to their advancements in irrigation and writing, they developed sophisticated systems of mathematics and astronomy. Their sexagesimal (base-60) numerical system underpins modern measurements of time and angles. Agricultural tools, wheeled vehicles, and early metallurgy also originated in Sumerian workshops, illustrating their ingenuity in addressing practical challenges.

Cylinder seal of the Uruk period and its impression, c. 3100 BCE, showing agricultural scenes. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cylinder seal of the Uruk period and its impression, c. 3100 BCE, showing agricultural scenes. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Art and architecture flourished under the Sumerians. Cylinder seals, intricately carved stone artifacts used to mark ownership and authenticate documents, exemplify their artistic craftsmanship. Monumental architecture, from ziggurats to city walls, reflects their capacity for large-scale construction and collective effort.

Silver model of a boat, tomb PG 789, Royal Cemetery of Ur, 2600–2500 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Legacy of the Sumerians

The Sumerians’ influence persisted long after their city-states were absorbed into larger empires, such as the Akkadian and Babylonian. Their innovations in writing, governance, and religion shaped the cultural foundation of Mesopotamia and beyond. Even as their language faded from common use, replaced by Akkadian, Sumerian texts continued to be studied and revered, ensuring their enduring legacy.

By creating the first known civilization, the Sumerians established a blueprint for societal complexity that resonated across the ancient world. Their achievements underscore the transformative potential of human ingenuity and cooperation, demonstrating how early societies navigated the challenges of environmental adaptation, resource management, and social organization to create enduring cultural structures.

References and further reading

- Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521533386

- Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, 1971, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226452388

- Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City, 2001, Allen Lane, ISBN: 978-0713991987

- Roaf, M., Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, 1990, Facts on File, ISBN: 978-0816022182

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 BC, 2024, Blackwell History of the Ancient World, ISBN: 978-1394210220

- Postgate, J. N., Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History, 1994, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415110327

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, The Sumerian World, 2013, Routledge, ISBN: 9780415569675

- Jeremy Black, Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson, Gabor Zolyomi, The literature of ancient Sumer, 2004, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9781423757122

- Wikipedia article on Sumerꜛ

comments