Overview of the religions of Mesopotamia: Pantheon and regional variations

The religions of Mesopotamia represent some of the earliest and most intricate expressions of humanity’s attempts to understand the cosmos, the natural world, and the human condition. Spanning several millennia and diverse cultures — including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians — Mesopotamian religion evolved into a complex of beliefs, practices, and rituals. The pantheon of Mesopotamian deities was vast, with gods and goddesses governing every aspect of life, from creation and fertility to war and death. At the same time, regional and temporal variations within Mesopotamia reflected the dynamic interactions between different city-states, empires, and cultural traditions.

Impression of a cylinder seal of the time of Akkadian King Sharkalisharri (c.2200 BC), with central inscription: “The Divine Sharkalisharri Prince of Akkad, Ibni-Sharrum the Scribe his servant”. Depiction of Ea with long-horned water buffalo. Circa 2217–2193 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Understanding Mesopotamian religion requires an exploration of its central pantheon, the cosmological framework underpinning its myths, and the distinctive regional practices that flourished in its diverse urban centers. The theological richness of Mesopotamian religion also reveals its profound influence on later civilizations, from the ancient Levant to Greco-Roman antiquity.

The pantheon: Structure and functions of the gods

The Mesopotamian pantheon was composed of a vast array of deities, often organized hierarchically and associated with specific domains of existence. The Sumerians, the earliest known inhabitants of Mesopotamia, established the foundation of this pantheon, which subsequent Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian traditions adapted and expanded.

At the head of the pantheon was Anu (Akkadian: An), the sky god and father of the gods, representing the overarching cosmic order. As the most senior deity, Anu’s role was largely symbolic, embodying authority and the heavens but rarely engaging directly in human affairs. His consort, Antu (or Ki in Sumerian), complemented his celestial dominion.

Symbols of various deities, including Anu (rightmost, second row) on a kudurru of Ritti-Marduk, from Sippar, Iraq, 1125–1104 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Below Anu were a triad of principal deities:

- Enlil, the god of air, storms, and kingship, played a pivotal role in Mesopotamian mythology and governance. As the chief deity of Nippur, Enlil was often depicted as a mediator between the divine and human realms, granting kings their legitimacy.

- Enki (Akkadian: Ea), the god of wisdom, water, and creation, was central to myths of civilization and invention. Associated with the city of Eridu, Enki was portrayed as a benevolent and cunning deity, providing humanity with knowledge and tools for survival.

- Ninhursag (or Ninmah), the earth and fertility goddess, symbolized the life-giving power of the land. She was often associated with childbirth and the nurturing aspects of nature.

Other major deities included Inanna (Akkadian: Ishtar), the goddess of love, war, and fertility, whose dynamic and multifaceted character made her one of the most widely venerated figures in Mesopotamian religion. Her epic tales, such as the Descent of Inanna, highlight themes of power, sexuality, and transformation. Sin (Sumerian: Nanna), the moon god, and Shamash (Sumerian: Utu), the sun god and patron of justice, further underscored the celestial dimension of the pantheon.

Left: Statuette of Enlil sitting on his throne from the site of Nippur, dated to 1800–1600 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Statue of a god (probably Ea), from Khorsabad, late 8th century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: The Silver vase of En-temena, which was dedicated to Ningirsu. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Inanna receiving offerings on the Uruk Vase, circa 3200–3000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Each deity was associated with specific symbols, attributes, and temples, often linked to the cities where their worship was concentrated. These cities served as religious centers, with ziggurats functioning as both architectural and spiritual focal points.

Cosmology and mythology: The Mesopotamian worldview

The cosmological framework of Mesopotamian religion depicted a universe governed by divine order, with the gods as the ultimate arbiters of fate. Central to this worldview was the concept of me, the divine decrees or principles that regulated the cosmos and human society. The gods were believed to control natural phenomena, social hierarchies, and individual destinies, requiring human reverence and offerings to maintain cosmic balance.

Creation myths, such as the Enuma Elish, articulated the origins of the world and the roles of the gods within it. In the Enuma Elish, Marduk, the Babylonian storm god, defeats the primordial chaos represented by Tiamat and establishes order by creating the heavens and earth from her body. This myth not only justified Marduk’s supremacy in the pantheon but also reflected broader themes of chaos, creation, and the struggle for order.

Other myths, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, explored existential themes of mortality, friendship, and the quest for meaning, offering insights into the human condition and the relationship between gods and mortals.

Ancient Mesopotamian terracotta relief showing Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven, which Anu gives to his daughter Ishtar in Tablet IV of the Epic of Gilgamesh after Gilgamesh spurns her amorous advances. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Regional religions and variations

While the Mesopotamian pantheon provided a shared theological framework, regional variations reflected the distinct identities and priorities of different city-states and empires.

Sumerian religion

The Sumerians established many of the foundational elements of Mesopotamian religion. Cities such as Uruk, Ur, Eridu, and Lagash were each associated with specific patron deities, whose worship shaped local practices. For instance, Uruk was the center of Inanna’s cult, while Eridu was dedicated to Enki. Sumerian religion emphasized agricultural fertility, community rituals, and temple worship, with ziggurats serving as central points of devotion.

Akkadian and Babylonian religion

The Akkadians and Babylonians integrated Sumerian deities into their own pantheon, adapting myths and rituals to reflect their cultural and political priorities. Under the Babylonians, Marduk rose to prominence as the chief deity, symbolizing the city’s dominance. The codification of religious texts, such as the Enuma Elish, reinforced Marduk’s status and articulated Babylon’s role as the center of divine order.

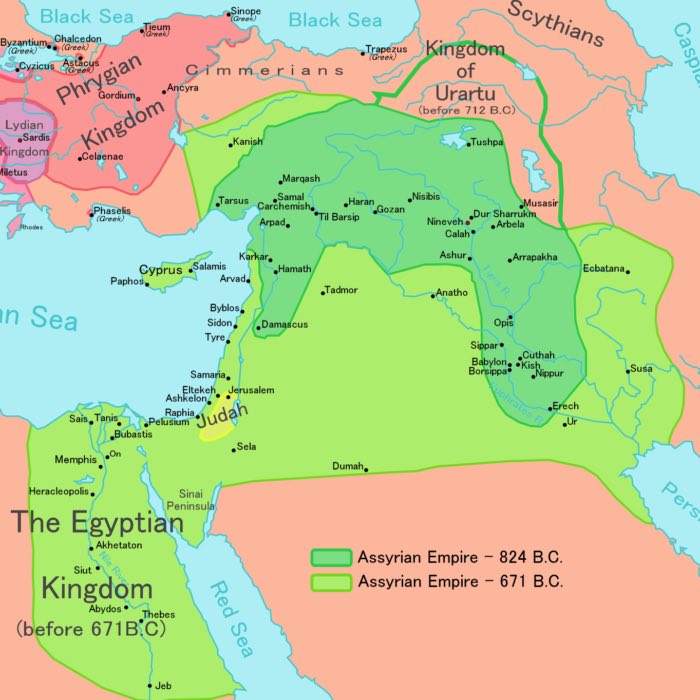

Assyrian religion

The Assyrians emphasized the martial and imperial aspects of religion, with their chief deity, Ashur, embodying kingship, warfare, and conquest. Ashur’s role evolved alongside the expansion of the Assyrian Empire, reflecting the integration of religion and statecraft. Assyrian kings often portrayed themselves as divinely chosen warriors, tasked with upholding the gods’ will through military campaigns.

Peripheral and local cults

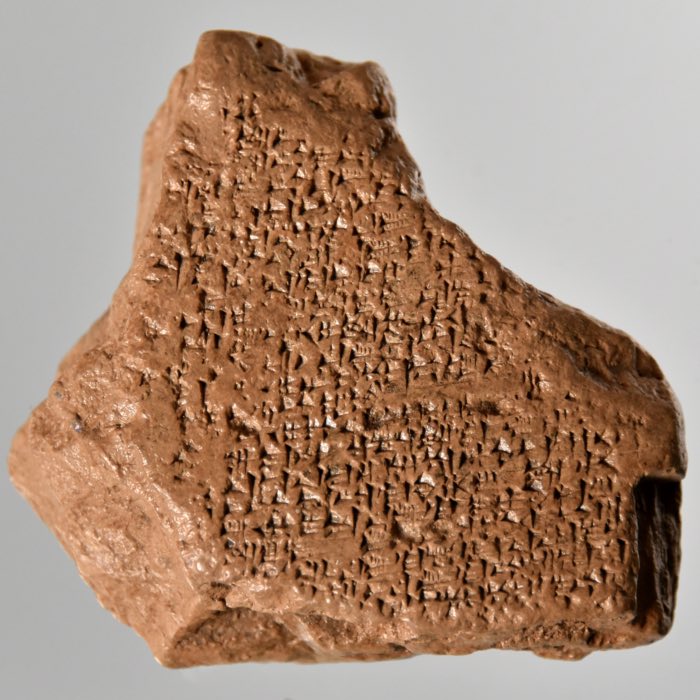

In addition to the major deities, numerous local and minor gods were worshiped across Mesopotamia, reflecting the diverse and decentralized nature of religious practice. These deities often served specific communities or functions, such as agricultural fertility, healing, or protection. Archaeological evidence, including votive offerings and inscriptions, highlights the localized nature of devotion.

Rituals, temples, and priesthood

Religious practice in Mesopotamia was centered on the temple, which functioned as both a spiritual and economic institution. Temples housed the statues of gods, believed to be their physical embodiments, and served as venues for sacrifices, offerings, and communal rituals.

The priesthood played a vital role in mediating between the human and divine realms. Priests performed daily rituals to care for the gods, including feeding, dressing, and anointing their statues. Festivals, such as the Akitu (New Year) festival in Babylon, brought together communities in celebrations that reaffirmed cosmic and social order.

Divination and astrology were integral aspects of Mesopotamian religion, reflecting the belief that the gods communicated their will through omens. Priests and specialists interpreted celestial phenomena, animal entrails, and other signs to guide political and personal decisions.

Legacy and influence

The religions of Mesopotamia profoundly influenced subsequent cultures and religious traditions. The polytheistic framework, mythological motifs, and ritual practices of Mesopotamian religion can be traced in the religious systems of the ancient Levant, Egypt, and Greece. For example, the biblical narratives of creation, the flood, and divine kingship show parallels with Mesopotamian myths, highlighting the interconnectedness of ancient Near Eastern cultures.

The integration of religion with governance and social structure, as exemplified by Mesopotamian city-states and empires, set a precedent for later civilizations, including the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman worlds.

Conclusion

The religions of Mesopotamia offer a profound insight into the spiritual, social, and intellectual life of one of humanity’s earliest civilizations. Through their pantheon, cosmology, and regional practices, the Mesopotamians articulated a worldview that sought to harmonize human existence with the divine and natural order. Their legacy endures in the myths, symbols, and religious ideas that continue to resonate across cultures and time.

References and further reading

- Bottéro, J., Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, 1995, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226067278

- Black, J., & Green, A., Gods, demons, and symbols of ancient Mesopotamia: an illustrated dictionary, 1992, British Museum Press, ISBN: 978-0714117058

- Jacobsen, T., The treasures of darkness: a history of Mesopotamian religion, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300022919

- Dalley, S., Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199538362

- Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia - The invention of the city, 2001, Allan Lane, ISBN: 9780713991987

comments