The ‘Out of Africa’ theory: Humanity’s origins and dispersal

The “Out of Africa” theory (OOA) is one of the most widely accepted models explaining the origins and global dispersal of modern Homo sapiens. Rooted in archaeological, genetic, and paleoanthropological evidence, this theory posits that modern humans first evolved in Africa before migrating to other parts of the world. This migration set the stage for the diversity and complexity of human societies, eventually leading to the development of civilizations.

The “Out of Africa” theory (OOA) suggests that modern humans originated in Africa and migrated to other parts of the world. The map shows the approximate successive dispersals (labeled in years before present) of Homo erectus greatest extent (yellow), Homo neanderthalensis greatest extent (ochre), and Homo sapiens (red). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Origins of Homo sapiens in Africa

The earliest evidence of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) dates back approximately 300,000 years, found in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco. Additional sites across Africa, such as Omo Kibish in Ethiopia (dated to about 195,000 years ago) and Herto in the Afar region, provide further support for Africa’s central role in human evolution. Fossil and genetic evidence collectively indicate that Africa was the cradle of humanity, where Homo sapiens emerged through a combination of environmental pressures and evolutionary adaptations from earlier hominin species such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis.

Key factors contributing to the evolution of modern humans in Africa include:

- Environmental diversity: Africa’s varied ecosystems, ranging from expansive savannas to dense forests and arid deserts, presented diverse challenges. These conditions likely spurred cognitive and technological advancements as humans adapted to hunt, gather, and innovate across different landscapes.

- Dietary adaptations: The abundance of food resources, including game animals, plant-based foods, and aquatic resources along rivers and lakes, shaped physiological traits such as brain size and energy efficiency. This dietary flexibility also contributed to the development of complex foraging and early tool-making behaviors.

- Genetic isolation and variation: Genetic studies reveal that African populations exhibit the greatest genetic diversity among modern humans. This diversity, rooted in long periods of regional isolation followed by periodic intermixing, provided the genetic adaptability necessary for migrations and environmental challenges worldwide. Such variation underscores Africa’s role as the source population for all Homo sapiens.

The first migrations out of Africa

Modern humans began migrating out of Africa in multiple waves, with the first significant dispersal occurring approximately 60,000–70,000 years ago. This migration was likely driven by environmental changes, resource scarcity, and population pressures. Homo sapiens followed coastlines and river systems, gradually spreading to the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and eventually Australia and the Americas:

The Levant and Middle East

Fossils and tools found at sites like Skhul and Qafzeh in Israel (dating to 100,000–120,000 years ago) represent some of the earliest evidence of Homo sapiens outside Africa. These early migrations, possibly linked to favorable climatic conditions, may have been short-lived as subsequent cooling periods made survival challenging. Despite their eventual disappearance, these populations laid the groundwork for later migratory waves.

Expansion of early modern humans from Africa through the Near East. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Expansion of early modern humans from Africa through the Near East. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: Red Sea crossing (map), which was likely one of the routes taken by early humans migrating out of Africa through the Near East and into Asia and Europe. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Detail of the Red Sea crossing, in particular the Bab-el-Mandeb strait (satellite image). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Asia and Australia

Genetic and archaeological evidence suggests a rapid migration across South Asia, facilitated by coastal routes and river systems, reaching Australia by 50,000 years ago. Sites like Madjedbebe in northern Australia provide evidence of early human settlement, showcasing advanced tools and adaptation to new ecosystems. This migration highlights humans’ remarkable ability to traverse vast distances and thrive in diverse environments.

This map shows the migration routes of modern humans within and Out of Africa, based on archaeogenetic data and environmental factors. It shows the northern route populating Western Eurasia, and the southern/coastal route populating Eastern Eurasia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

This map shows the migration routes of modern humans within and Out of Africa, based on archaeogenetic data and environmental factors. It shows the northern route populating Western Eurasia, and the southern/coastal route populating Eastern Eurasia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Europe

Homo sapiens entered Europe around 40,000 years ago, marking a significant encounter with Neanderthals. Genetic studies confirm interbreeding between the two species, leaving a legacy of Neanderthal DNA in modern non-African populations. Archaeological evidence, such as Aurignacian tools and cave art, reflects cultural exchanges and the eventual dominance of Homo sapiens in the region.

The Americas

Migration into the Americas occurred much later, approximately 15,000–20,000 years ago, via the Bering land bridge during the Last Glacial Maximum. Coastal routes along the Pacific also played a vital role. Sites like Monte Verde in Chile indicate early human presence far south of the land bridge, demonstrating rapid and adaptive settlement strategies in new environments.

Genetic and archaeological evidence

The “Out of Africa” theory finds robust support in both genetic studies and archaeological discoveries, providing a comprehensive picture of human origins and dispersal.

Genetic evidence

The “Out of Africa” theory finds robust support in genetic studies, which provide compelling evidence for the African origins of modern humans. One of the most significant lines of evidence comes from mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis, which reveals that all modern humans trace their maternal lineage to a single African population often referred to as “Mitochondrial Eve”. This finding underscores the shared ancestry of all living humans and the central role of Africa in human evolution.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of DNA data of ancient and modern day individuals from worldwide populations. Oceanians (Aboriginal Australians and Papuans) are most differentiated from both East-Eurasians and West-Eurasians. Gray labels represent population codes showing coordinates for individuals. Colored circles indicate ancient individuals. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Principal component analysis (PCA) of DNA data of ancient and modern day individuals from worldwide populations. Oceanians (Aboriginal Australians and Papuans) are most differentiated from both East-Eurasians and West-Eurasians. Gray labels represent population codes showing coordinates for individuals. Colored circles indicate ancient individuals. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

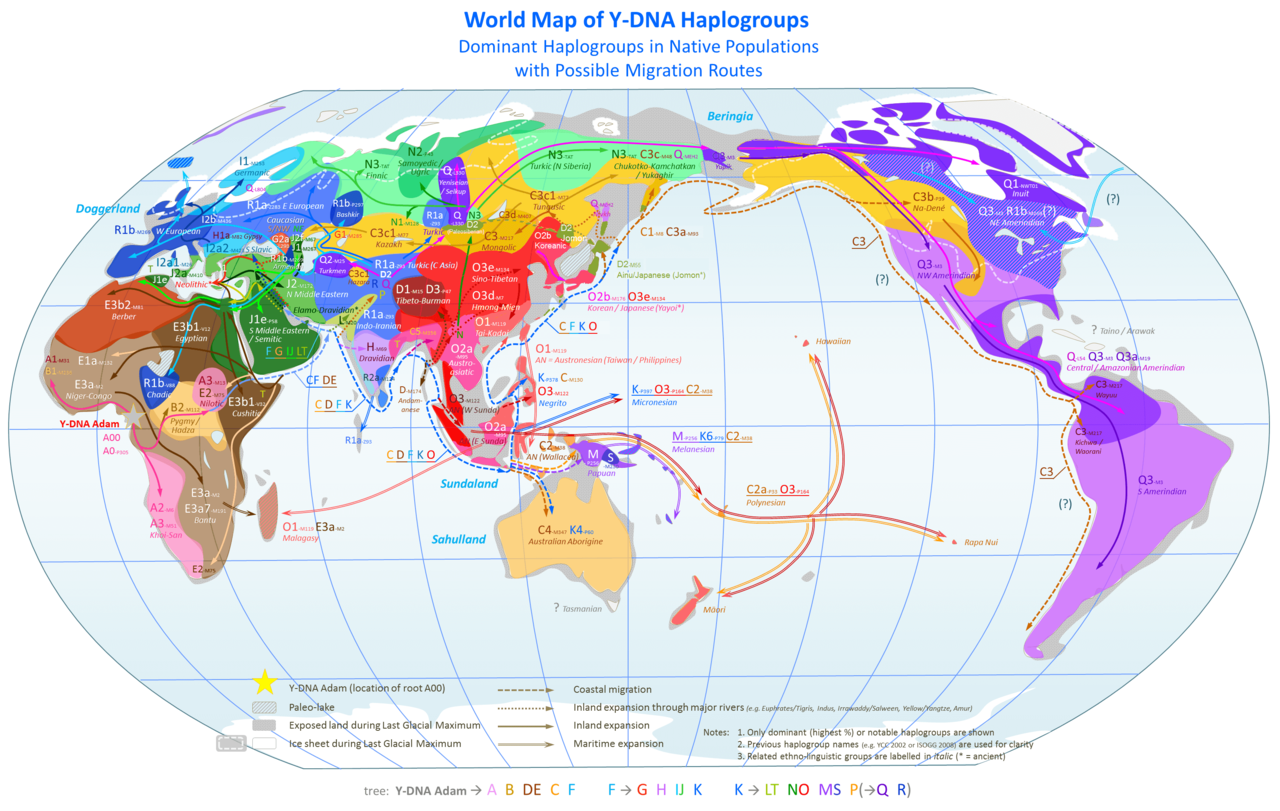

Similarly, studies of the Y-chromosome, which tracks paternal lineages, confirm African origins, demonstrating congruence between maternal and paternal genetic evidence. These patterns highlight the migratory pathways of early humans as they dispersed across continents.

PCA calculated on DNA data of present-day and ancient individuals from eastern Eurasia and Oceania. PC1 (23,8%) distinguishes East-Eurasians and Australo-Melanesians, while PC2 (6,3%) differentiates East-Eurasians along a North to South cline. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

PCA calculated on DNA data of present-day and ancient individuals from eastern Eurasia and Oceania. PC1 (23,8%) distinguishes East-Eurasians and Australo-Melanesians, while PC2 (6,3%) differentiates East-Eurasians along a North to South cline. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Furthermore, genomic diversity offers another layer of support. African populations display the greatest genetic variation among all human groups, reflecting a longer evolutionary history compared to populations in other regions. This genetic diversity, shaped by the extensive time Homo sapiens spent evolving in Africa before migrating outward, underscores the continent’s foundational role in the story of human development.

Archaeological evidence

Archaeological discoveries provide tangible support for the “Out of Africa” theory, complementing genetic evidence with material insights into human migrations. Stone tools discovered in the Arabian Peninsula, for example, point to early human presence during significant migration waves out of Africa. These tools, often associated with sophisticated hunting and processing techniques, reveal the adaptive strategies early humans employed as they ventured into new environments.

Layer sequence at Ksar Akil in the Levantine corridor, and discovery of two fossils of Homo sapiens, dated to 40,800 to 39,200 years BP for ‘Egbert’, and 42,400–41,700 BP for ‘Ethelruda’. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Layer sequence at Ksar Akil in the Levantine corridor, and discovery of two fossils of Homo sapiens, dated to 40,800 to 39,200 years BP for ‘Egbert’, and 42,400–41,700 BP for ‘Ethelruda’. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Europe and Asia, cave paintings and artifacts offer a glimpse into the cultural and technological innovations that accompanied these migrations. Sites like Lascaux in France and Chauvet Cave showcase intricate depictions of animals and symbolic motifs, indicating advanced cognitive and artistic abilities. These cultural artifacts also highlight how migrating populations preserved and adapted their traditions to diverse ecological settings.

Anatomically Modern Humans known archaeological remains in Europe and Africa, directly dated, calibrated carbon dates as of 2013. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Anatomically Modern Humans known archaeological remains in Europe and Africa, directly dated, calibrated carbon dates as of 2013. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

In the Americas, the Clovis culture, characterized by distinct fluted projectile points, exemplifies the ingenuity of human populations adapting to novel ecosystems. Found across North America, these tools reflect a blend of technological innovation and environmental knowledge, marking a significant milestone in human adaptation and cultural expression during the peopling of the Americas.

The earliest-branching non-African paternal lineages (C, D, F) after the Out-of-Africa event (a), and their deepest divergence among modern day East or Southeast Asia (b), suggesting rapid coastal expansions. Simplified Y-chromosome tree is shown as reference for colours. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The earliest-branching non-African paternal lineages (C, D, F) after the Out-of-Africa event (a), and their deepest divergence among modern day East or Southeast Asia (b), suggesting rapid coastal expansions. Simplified Y-chromosome tree is shown as reference for colours. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Implications for civilization development

The “Out of Africa” theory underscores the shared origins of humanity while highlighting the remarkable adaptability that allowed humans to thrive in diverse environments. This adaptability laid the groundwork for transformative developments that would later define the trajectory of civilizations. As humans migrated, they established settlements in ecologically favorable regions, choosing areas with abundant resources, such as river valleys and fertile plains, which eventually became the nuclei of later complex societies. These settlements provided the stability necessary for agricultural experimentation, social organization, and population growth.

Migration also facilitated the exchange of ideas, tools, and practices, enriching human cultures and spurring innovation. For example, early humans developed and refined stone tools, navigational techniques, and hunting strategies, which were shared and adapted as populations moved into new ecological niches. This dynamic process of cultural and technological innovation set the stage for the later advancements seen in early civilizations.

Moreover, regional adaptations to different climates and resources led to the emergence of distinct cultures, languages, and societal structures. Populations in temperate zones developed tools and shelters suited for cold weather, while those in tropical regions adapted to humid environments and diverse ecosystems. These variations fostered a rich human diversity, which would later influence the cultural and technological uniqueness of emerging civilizations.

Links to early civilizations

Map of the world showing approximate centres of origin of agriculture and its spread in prehistory: the Fertile Crescent (11,000 Before Present (BP)), the Yangtze and Yellow River basins (9,000 BP) and the Papua New Guinea Highlands (9,000–6,000 BP), Central Mexico (5,000–4,000 BP), Northern South America (5,000–4,000 BP), sub-Saharan Africa (5,000–4,000 BP, exact location unknown), eastern North America (4,000–3,000 BP). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of the world showing approximate centres of origin of agriculture and its spread in prehistory: the Fertile Crescent (11,000 Before Present (BP)), the Yangtze and Yellow River basins (9,000 BP) and the Papua New Guinea Highlands (9,000–6,000 BP), Central Mexico (5,000–4,000 BP), Northern South America (5,000–4,000 BP), sub-Saharan Africa (5,000–4,000 BP, exact location unknown), eastern North America (4,000–3,000 BP). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

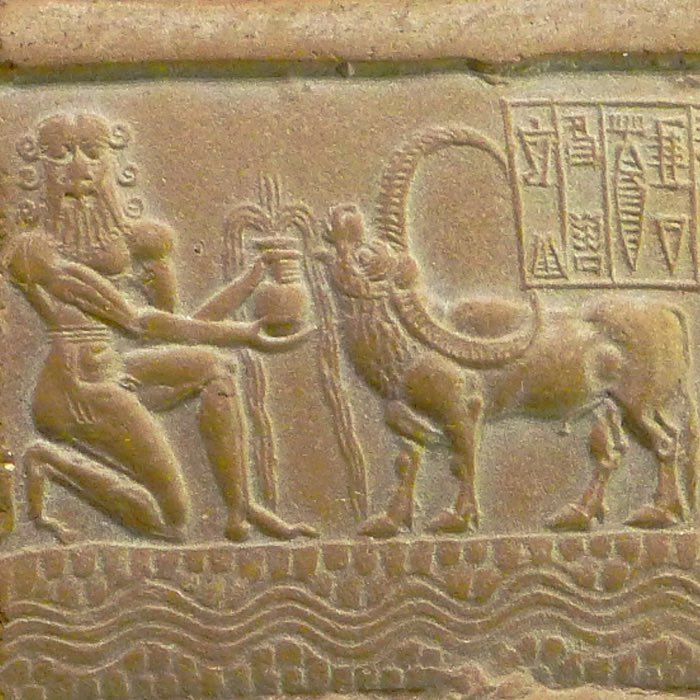

Mesopotamia and the fertile crescent

The agricultural revolution in Mesopotamia, often regarded as the cradle of civilization, was preceded by thousands of years of hunter-gatherer migrations and adaptations. These early populations learned to exploit the fertile alluvial plains of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, developing methods of irrigation and plant cultivation that would later support urban centers like Uruk and Babylon. Their innovations in agriculture and resource management laid the foundation for the complex societal structures that characterized Mesopotamian civilization.

Map of Southwest Asia showing the main archaeological sites of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, c. 7500 BCE, in the ‘Fertile Crescent’. This period marks the transition to agrarian lifestyles. The map illustrates the early centers of human settlement in the Near East, beginning in the Levant and subsequently expanding agriculture into the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of Southwest Asia showing the main archaeological sites of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, c. 7500 BCE, in the ‘Fertile Crescent’. This period marks the transition to agrarian lifestyles. The map illustrates the early centers of human settlement in the Near East, beginning in the Levant and subsequently expanding agriculture into the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

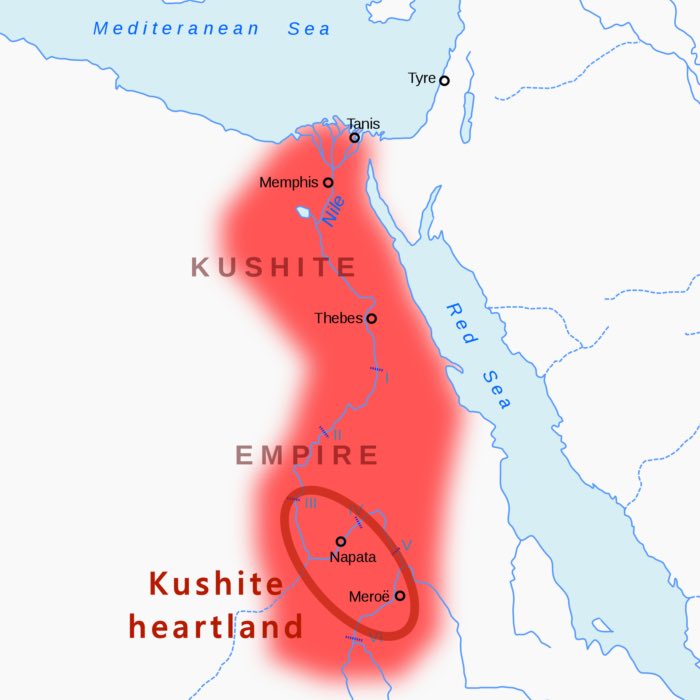

Egypt and the Nile Valley

The settlement of the Nile Valley exemplifies human ingenuity in adapting to riverine ecosystems. Early populations, drawn by the annual flooding of the Nile and its nutrient-rich silt, established a sustainable agricultural base that supported increasingly complex social and political organizations. Skills honed during earlier migrations, such as water management and communal cooperation, were instrumental in transforming the Nile Valley into one of the most enduring centers of ancient civilization.

Map of ancient Egypt, showing major cities and sites of the Dynastic period (c. 3150 to 30 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

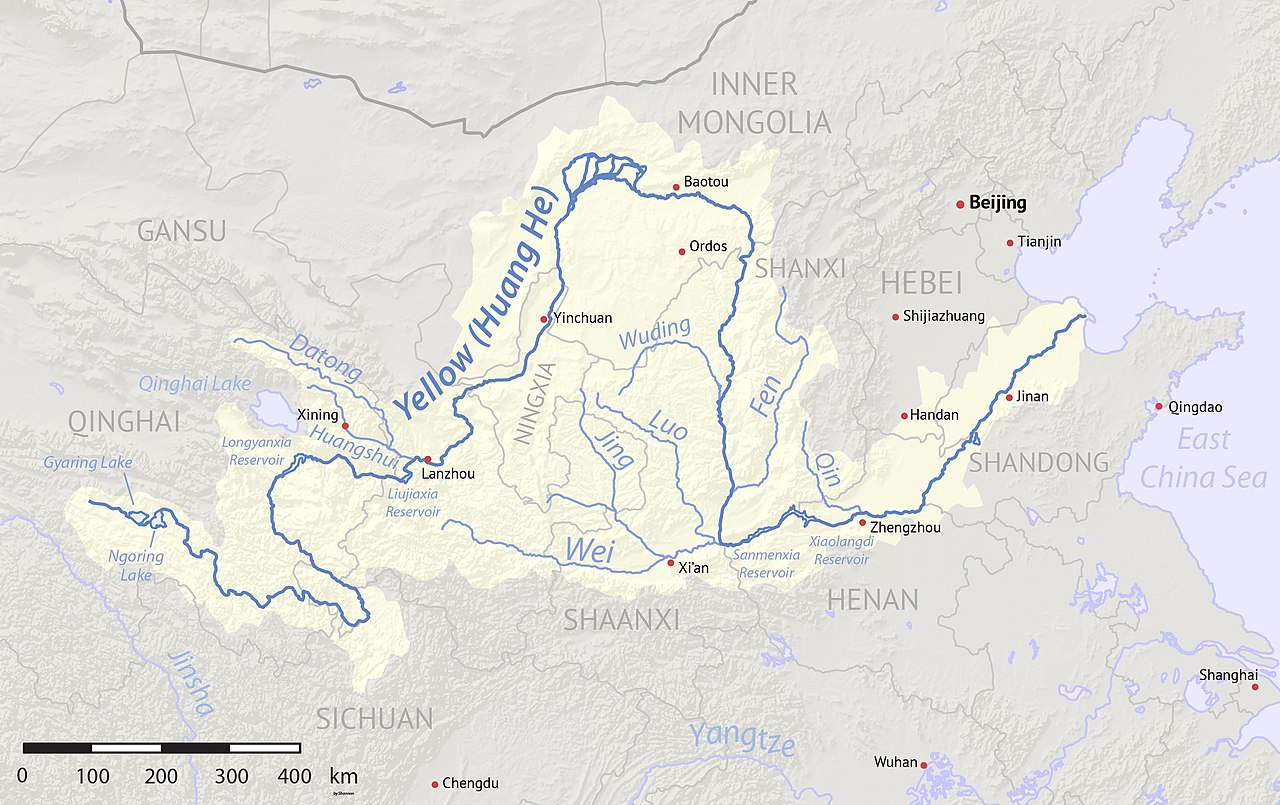

China and the Yellow River

In East Asia, early human populations brought with them stone tool technologies and farming practices that enabled the settlement of the Yellow River basin. The fertile loess soils of this region supported the cultivation of millet and rice, underpinning the rise of Neolithic cultures such as the Yangshao and Longshan. These communities laid the groundwork for the emergence of dynastic China, demonstrating the transformative impact of early agricultural and technological adaptations.

Map of the Yellow River, whose watershed covers most of northern China and drains to the Yellow Sea. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Map of the Yellow River, whose watershed covers most of northern China and drains to the Yellow Sea. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Americas

The migration of humans into the Americas via the Bering land bridge and subsequent coastal routes paved the way for the development of complex societies such as the Olmec, Maya, and Inca civilizations. Early settlers adapted to diverse environments ranging from the Arctic tundra to tropical rainforests and high-altitude Andean plateaus. Their innovative approaches to agriculture, such as the construction of terraced fields and the domestication of crops like maize, were key factors in the flourishing of these civilizations.

Simple map of subsistence methods in the Americas at 1000 BCE. Yellow: hunter-gatherers, Green: simple farming societies, Orange: complex farming societies (tribal chiefdoms or civilizations). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Challenges and alternate theories

While the “Out of Africa” theory remains the most widely accepted model, alternate models, such as the “Multiregional Hypothesis”, have suggested that modern humans evolved simultaneously in multiple regions from earlier hominin populations. Proponents of this hypothesis argue for localized evolutionary continuities between archaic humans and modern populations. However, these models are less supported by the extensive genetic evidence, which overwhelmingly points to a single African origin for modern Homo sapiens.

Recent advances in genomics and archaeology continue to refine our understanding of early human migrations, revealing a more complex picture of interactions with other archaic human species. For instance, genetic studies have shown that Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals in Europe and Asia, contributing approximately 1-2% of the DNA found in modern non-African populations. Similarly, Denisovans, an enigmatic group of archaic humans identified through fossil DNA from Siberia, also interbred with early modern humans, particularly those migrating into Southeast Asia and Oceania. These interbreeding events highlight a dynamic period of coexistence and genetic exchange, enriching the evolutionary story of Homo sapiens and shaping their adaptations to diverse environments.

Conclusion and upcoming posts

The “Out of Africa” theory offers a cohesive narrative for humanity’s origins and dispersal, highlighting our shared ancestry and the adaptive diversity that enabled humans to thrive globally. By tracing these migratory journeys, we uncover the resilience, innovation, and cooperation that allowed early humans to overcome environmental challenges. These migrations not only spread human populations but also facilitated the exchange of ideas, tools, and practices, laying the foundation for diverse cultures and complex societies. This narrative connects our biological origins to the cultural and technological achievements that define human history, serving – in my opinion – as a compelling introduction to the broader story of civilization’s rise and the enduring legacy of human ingenuity.

Map of Y-chromosome haplogroups – dominant haplogroups in pre-colonial populations with proposed migrations routes. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of Y-chromosome haplogroups – dominant haplogroups in pre-colonial populations with proposed migrations routes. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

My research into the “Out of Africa” theory has actually inspired me to further explore how human societies have evolved and interacted around the globe. I will therefore continue with a series of posts exploring the specific regions and cultures that emerged from these ancient migrations, hopefully shedding some light on the diverse paths that human societies took in their development and explore the rich diversity of human cultures that emerged from these ancient migrations. Here’s what’s coming up:

1. Mesopotamian civilization – Exploring the the roots of urbanization, governance, and culture in one of humanity’s first cradles of civilization:

- The emergence of civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt: A comparative analysis

- The Sumerians: The first civilization

- Uruk: The first mega-city of humanity

- The Akkadian Empire: The first unified empire in history

- Ur and the Neo-Sumerian period: The resurgence of Sumerian civilization

- Babylon and the rise of Hammurabi: Foundations of Mesopotamian hegemony

- The Hittite Empire

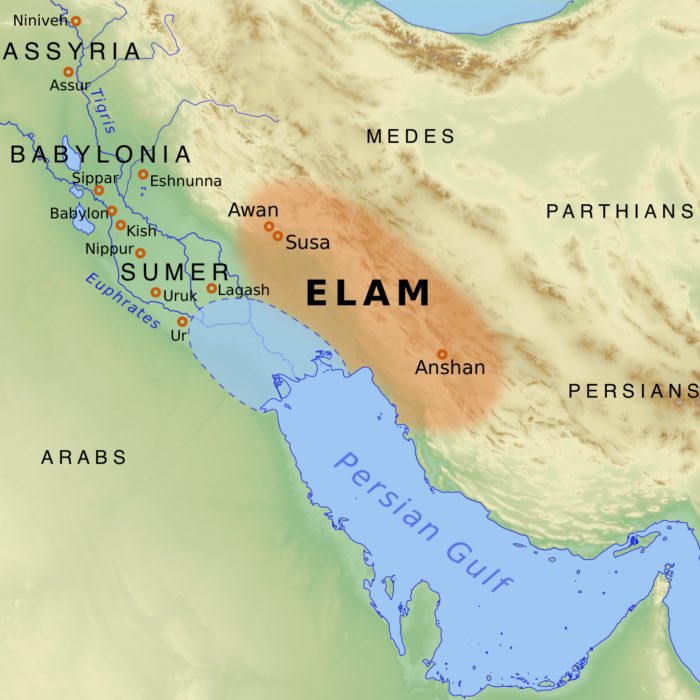

- The Elamite civilization

- Mesopotamian trade networks

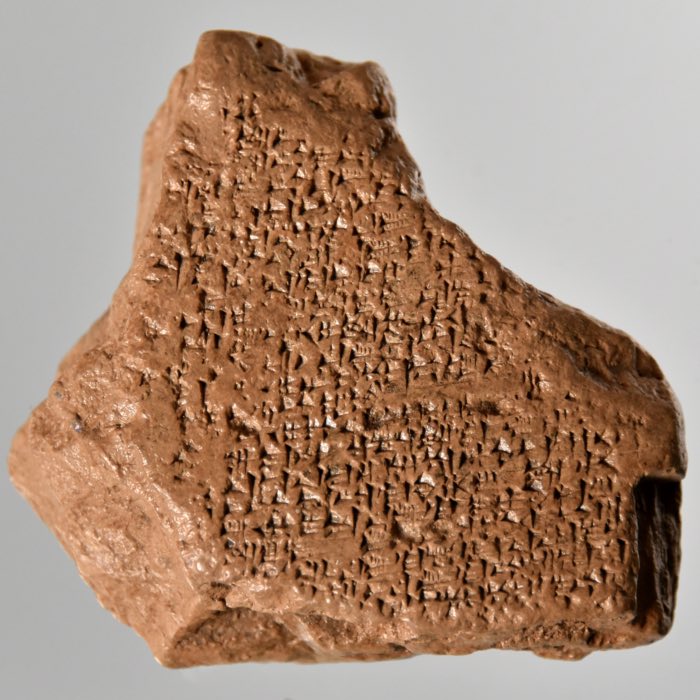

- Technologies and sciences of Mesopotamia

- The Babylonian creation myth

- The Epic of Gilgamesh

- Ugarit: A crossroads of ancient cultures

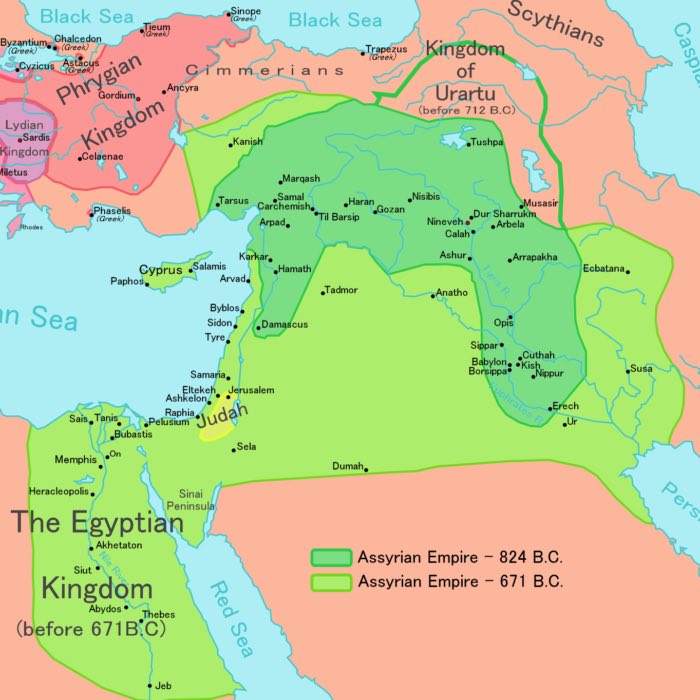

- Assyria and Nineveh

2. Religious and cultural legacy of Mesopotamia – Religious beliefs, myths, and cultural practices that shaped the ancient Mediterranean and Near East world:

- Overview of the religions of Mesopotamia

- The influence of Mesopotamian religions on neighboring civilizations

- Zoroastrianism

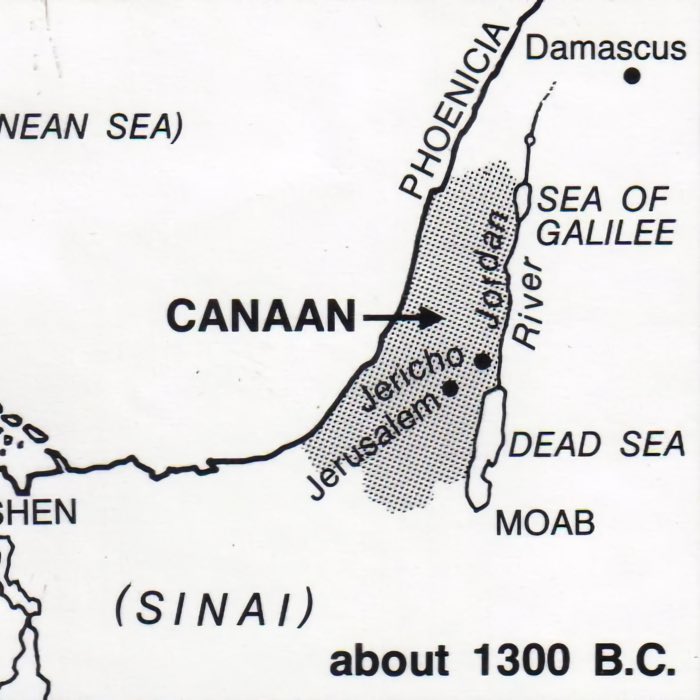

3. The Canaanites – Cultural and religious bridge of the ancient Near East:

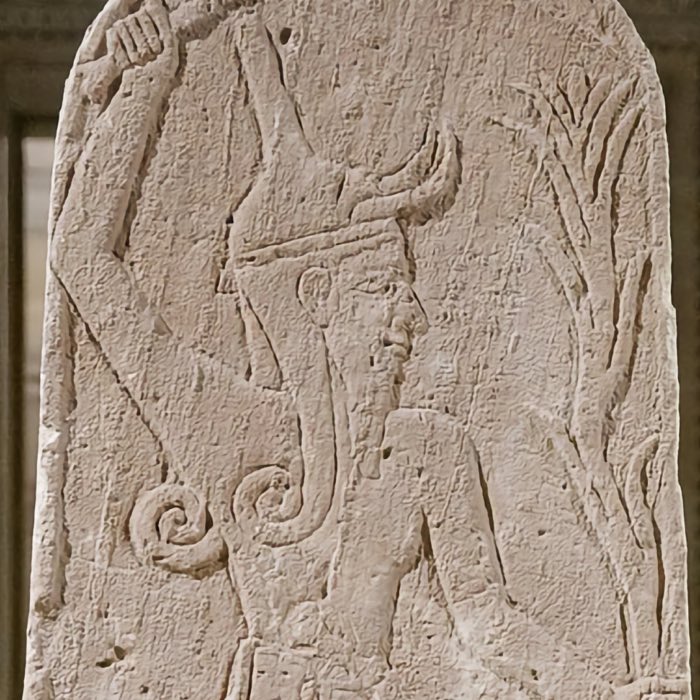

- The Canaanite civilization

- The Canaanite religion and its influence on the early development of Judaism

4. Aegean civilizations – Uncovering the earliest maritime cultures of the Mediterranean:

5. East Asian civilizations – Charting the unique developments of early societies in East Asia:

6. Indian subcontinent – Philosophical and urban innovations of ancient India:

- The development of Indian civilization

- The Vedas: Foundations of Indian civilization

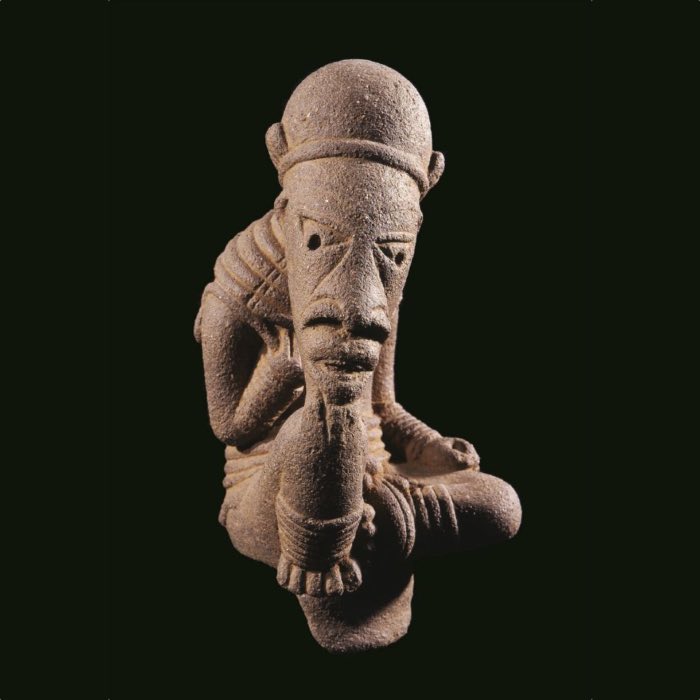

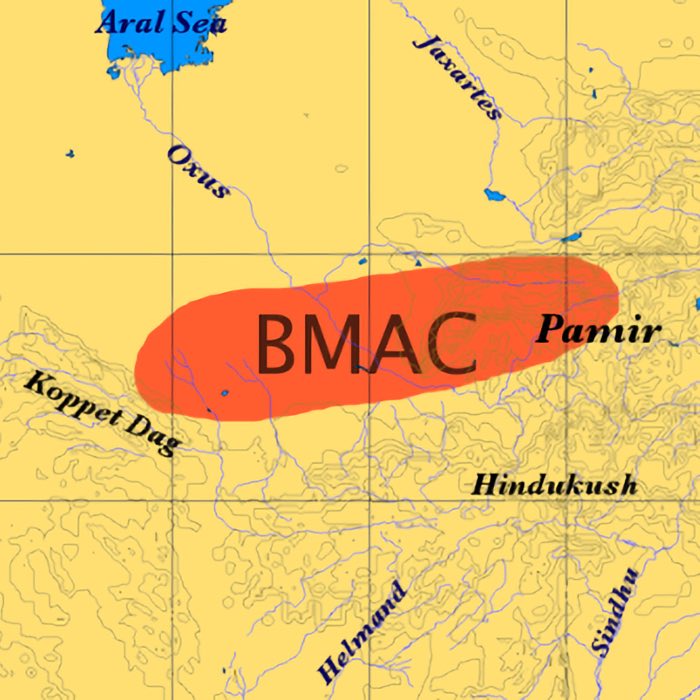

- The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)

7. African civilizations – Highlighting the rich history of Africa’s early societies, exemplified by:

8. American civilizations – Investigating ancient societies in the Americas:

9. Synthesis and reflection – Summarizing some key themes and insights:

- A comprehensive overview of early civilizations

- Multicultural interconnections and independent developments in early civilizations

References and further reading

- Richard G. Klein, The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins, 2009, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226439655

- Chris Stringer, The Origin of Our Species, 2012, Allen Lane, ISBN: 978-1846141409

- Svante Pääbo, Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes, 2014, Basic Books, ISBN: 978-0465054954

- Ian Tattersall, Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins, 2012, St. Martin’s Griffin, ISBN: 978-1137278302

- Jean-Jacques Hublin and Shannon P. McPherron (Eds.), Modern Origins: A North African Perspective, 2012, Springer, ISBN: 978-9400729285

- Clive Gamble, Settling the Earth: The Archaeology of Deep Human History, 2013, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1107601079

- Peter Bellwood, First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective, 2013, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405189088

- Curtis Marean, The Most Invasive Species of All Time: The Colonization of the Globe by Modern Humans, 2015, Princeton University Press (in edited volume), doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0815-32ꜛ

- Robin Dennell, The Palaeolithic Settlement of Asia, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1598744705

- Stephen Oppenheimer, Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World, 2004, Robinson Publishing, ISBN: 978-1841198941

- Diamond, J., Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions, 2003, Science 300: 597–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1078208ꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Out of Africa theoryꜛ

comments