Nineveh: The crown jewel of the Neo-Assyrian empire

Nineveh, one of the most illustrious cities of the ancient world, served as the final capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and a center of political, cultural, and architectural innovation. Situated on the eastern bank of the Tigris River near modern-day Mosul in Iraq, Nineveh was a city of immense grandeur and significance. Its prominence was not only a symbol Assyrian power but also a reflection of its rulers’ ambitions to craft a city that embodied their dominance and vision for the ancient Near East.

Artist’s impression of Assyrian palaces from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Nineveh reached its zenith during the reign of Ashurbanipal in the 7th century BCE, becoming a hub of intellectual, artistic, and administrative achievements. The city’s grandeur and eventual destruction in 612 BCE encapsulate the dramatic rise and fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, providing an enduring legacy in both historical records and cultural memory.

Origins and early history

Nineveh’s origins trace back to the early third millennium BCE, with archaeological evidence suggesting continuous habitation for thousands of years. Initially a modest settlement, Nineveh gained prominence during the Middle Assyrian period (ca. 1350–1000 BCE) as a regional administrative center. Its strategic location near the Tigris River and its position on key trade routes linking Mesopotamia with Anatolia and the Levant contributed to its growth.

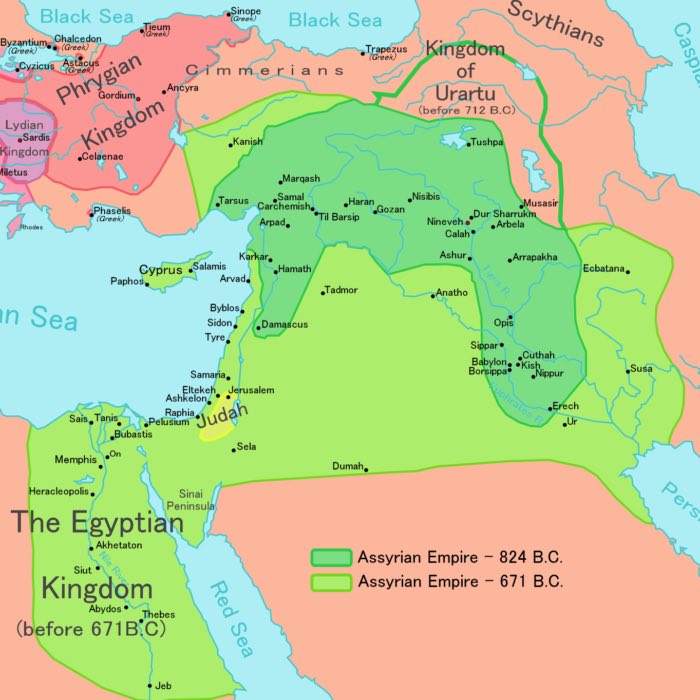

The ancient Assyrian heartland (red) and the later Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 7th century BCE (orange). Niniveh is indicatet by a red dot. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The ancient Assyrian heartland (red) and the later Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 7th century BCE (orange). Niniveh is indicatet by a red dot. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The city’s patron deity was Ishtar, the goddess of love, war, and fertility, whose temple, the E-mashmash, was one of Nineveh’s most significant religious sites. Devotion to Ishtar underscores Nineveh’s early role as both a spiritual and commercial hub, with religious practices closely tied to its civic identity.

Left: Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler, discovered in Nineveh in 1931, presumably depicting Sargon of Akkad’s son Manishtushu, c. 2270 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Painted jar, Ninevite 5 period (c. 3000-2700 BCE), from Nineveh. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nineveh as the Neo-Assyrian capital

Nineveh reached the height of its glory during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, particularly under the reign of Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BCE). Sennacherib transformed Nineveh into the empire’s capital, embarking on an ambitious program of urban development that reshaped the city into a monumental center of power and administration.

Left: Simplified representation of the city wall with the gates. The Kujundschik and Nebi Jenus excavation mounds can also be seen. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Palace remains and temple complex on the Kujundschik. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The city was fortified with massive walls stretching approximately 12 kilometers, encompassing an area of over 750 hectares. These walls, punctuated by 15 gates, were among the largest and most impressive defensive structures of their time. Inside the city, Sennacherib commissioned grand palaces, temples, and gardens, including what some scholars speculate may have been the inspiration for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Sennacherib’s “Palace Without Rival” epitomized Nineveh’s splendor. Decorated with intricate reliefs, the palace served as both a royal residence and a statement of Assyrian dominance. The reliefs depict scenes of military conquest, religious rituals, and the king’s achievements, illustrating the interconnectedness of power, divinity, and art in Assyrian ideology.

Artist’s impression of a hall in an Assyrian palace from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Artist’s impression of a hall in an Assyrian palace from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Under Sennacherib, Nineveh also became a center of technological innovation. The city’s extensive canal and aqueduct systems brought water from distant sources, ensuring a reliable supply for its inhabitants and its famed gardens. This hydraulic engineering reflects the Neo-Assyrian emphasis on controlling and transforming the environment to reinforce imperial authority.

Restored Adad Gate, taken prior to the gate’s destruction by ISIL in April 2016. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nineveh under Ashurbanipal: A hub of culture and learning

Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BCE), one of Assyria’s most renowned rulers, further enhanced Nineveh’s status, not only as a political capital but also as a cultural and intellectual center. His reign is particularly notable for the establishment of the Library of Ashurbanipal, a vast collection of texts that preserved the knowledge of Mesopotamia and beyond.

The walls of Nineveh at the time of Ashurbanipal. 645–640 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The walls of Nineveh at the time of Ashurbanipal. 645–640 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

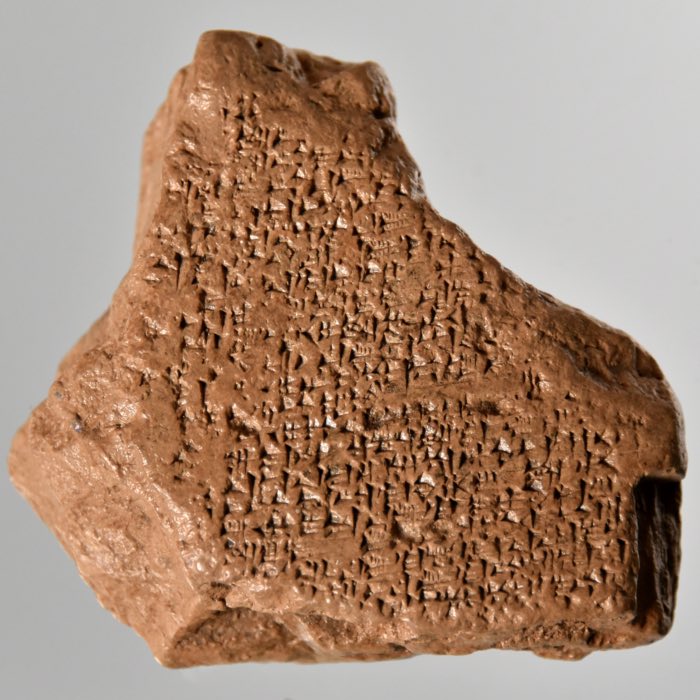

The library housed thousands of cuneiform tablets, encompassing a wide range of subjects, including mythology, astronomy, medicine, and law. Among its most famous holdings are the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Enuma Elish (Babylonian creation myth), and numerous scholarly and administrative texts. Ashurbanipal’s library reflects the king’s ambition to compile and safeguard the intellectual heritage of the ancient world, creating a repository of knowledge that has proven invaluable to modern scholarship.

Relief of Ashurbanipal hunting a Mesopotamian lion, from the Northern Palace in Nineveh, 645-635 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Relief of Ashurbanipal hunting a Mesopotamian lion, from the Northern Palace in Nineveh, 645-635 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nineveh during Ashurbanipal’s reign also witnessed a flourishing of artistic and literary expression. The palace reliefs from this period depict detailed scenes of the king’s lion hunts, military victories, and royal ceremonies, showcasing the technical and aesthetic sophistication of Assyrian art. These works not only glorified the king but also conveyed the themes of divine favor and imperial order.

Religion and spiritual significance

Religion played a central role in Nineveh’s identity, with the worship of Ishtar as its focal point. The city’s temples and rituals reinforced the connection between divine will and Assyrian power, emphasizing the king’s role as a mediator between the gods and his people.

In addition to Ishtar, Nineveh’s pantheon included other major Assyrian deities, such as Ashur, the supreme god of the empire, and Nabu, the god of wisdom and writing. Religious festivals, including those dedicated to Ishtar, were occasions of communal participation and political affirmation, reinforcing the city’s position as a spiritual heart of the empire.

The fall of Nineveh

Despite its grandeur, Nineveh’s fate was tied to the fortunes of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. By the late 7th century BCE, Assyria faced mounting challenges, including internal instability, economic strain, and external pressures from emerging powers such as the Medes and Babylonians.

In 612 BCE, a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, and Scythians besieged Nineveh. The city fell after intense fighting, and its destruction marked the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Archaeological evidence reveals widespread devastation, with many of Nineveh’s grand structures reduced to rubble. The fall of Nineveh was so complete that the city disappeared from historical records, becoming a symbol of divine retribution and imperial hubris in later traditions, including the Hebrew Bible.

Legacy and rediscovery

Although Nineveh was abandoned as a political center, its legacy endured through its contributions to art, architecture, and scholarship. The Library of Ashurbanipal, rediscovered during 19th-century excavations, has provided unparalleled insights into Mesopotamian history, literature, and science. The city’s monumental reliefs and artifacts, now housed in museums around the world, continue to inspire awe and admiration.

Nineveh’s rediscovery in the 19th century marked a turning point in the study of ancient Mesopotamia, with archaeologists such as Austen Henry Layard uncovering its palaces, temples, and archives. These findings have illuminated the grandeur of Assyrian civilization, offering a glimpse into one of history’s most extraordinary urban centers.

Conclusion

Nineveh represents the heights of Assyrian ambition and the complexities of ancient imperial rule. Its grandeur as the Neo-Assyrian capital, its contributions to art and scholarship, and its dramatic fall encapsulate the rise and fall of one of history’s great civilizations. As both a physical and symbolic entity, Nineveh reflects the interplay between power, culture, and memory in the ancient Near East.

References and further reading

- Reade, J. E., Assyrian Sculpture, 1998, British Museum Press, ISBN: 978-0714121413

- Kuhrt, A., The Ancient Near East, c. 3000–330 BC, 1997, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 978-0415167635

- Radner, K., & Robson, E., The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, 2020, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198856030

- Grayson, A. K., Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC, 1991, University of Toronto Press, ISBN: 978-0802059659

comments