Mesopotamian technologies and sciences: The foundations of human progress

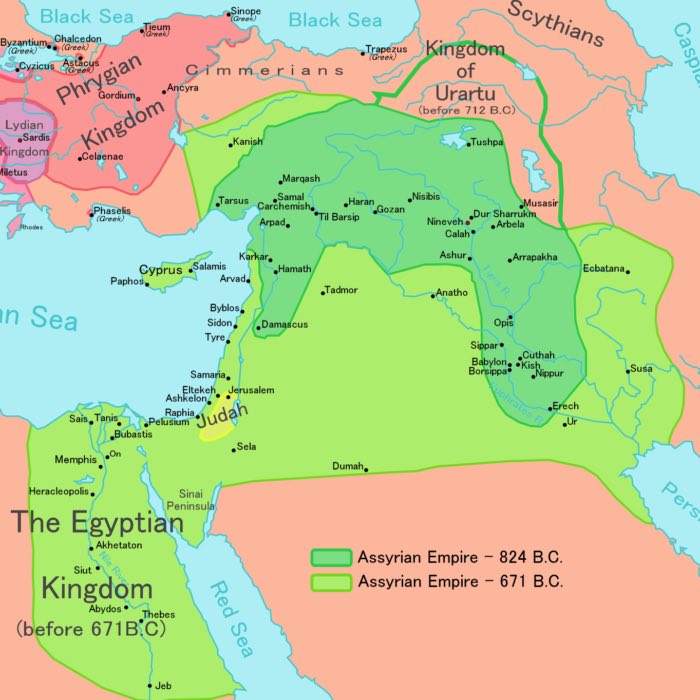

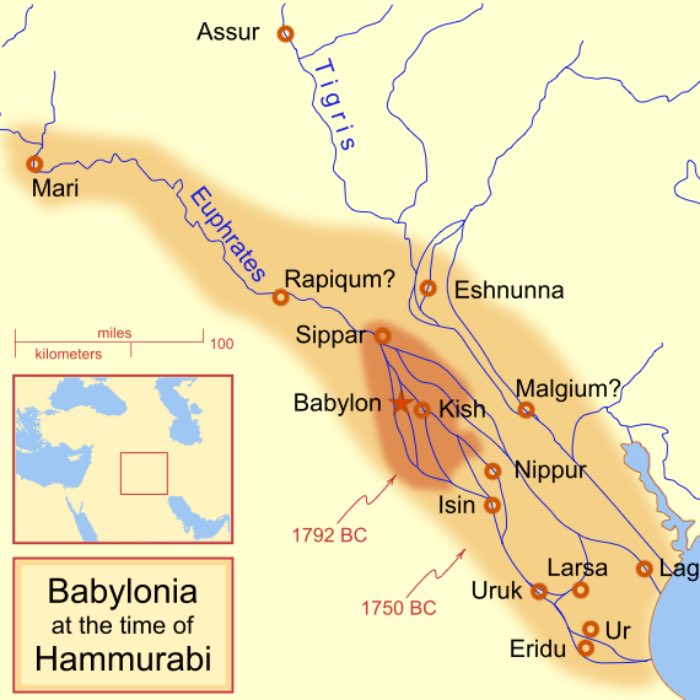

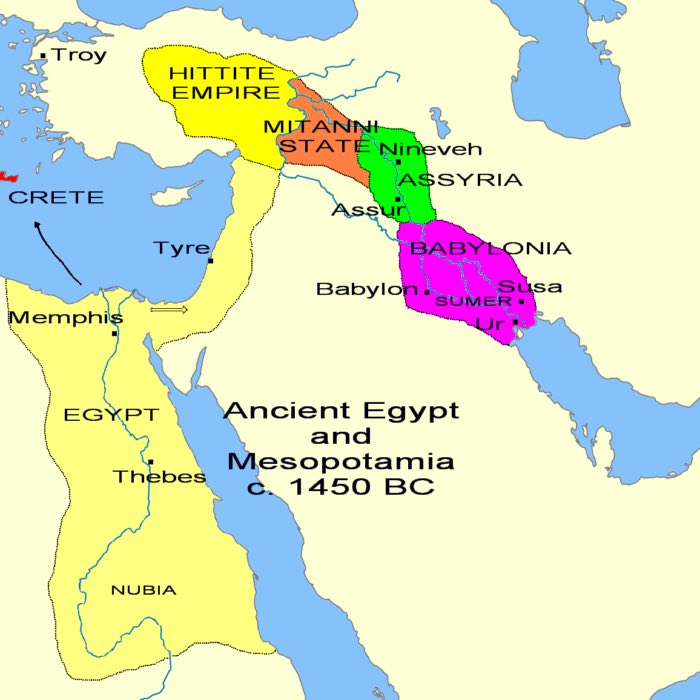

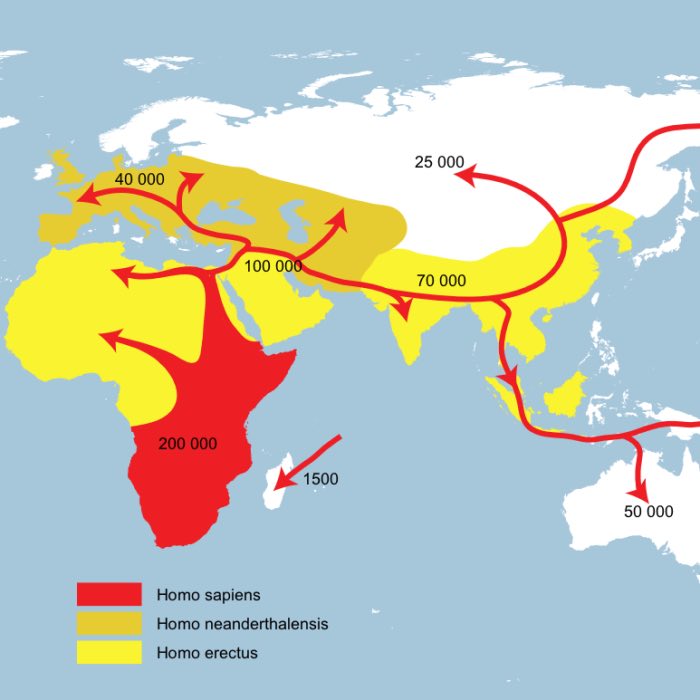

The ancient Mesopotamians, inhabitants of the fertile region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, were pioneers in the development of techniques and sciences that profoundly influenced the trajectory of human civilization. From innovative agricultural practices and engineering feats to the formulation of mathematical, astronomical, and medical knowledge, Mesopotamia represents a crucible of early scientific and technological progress.

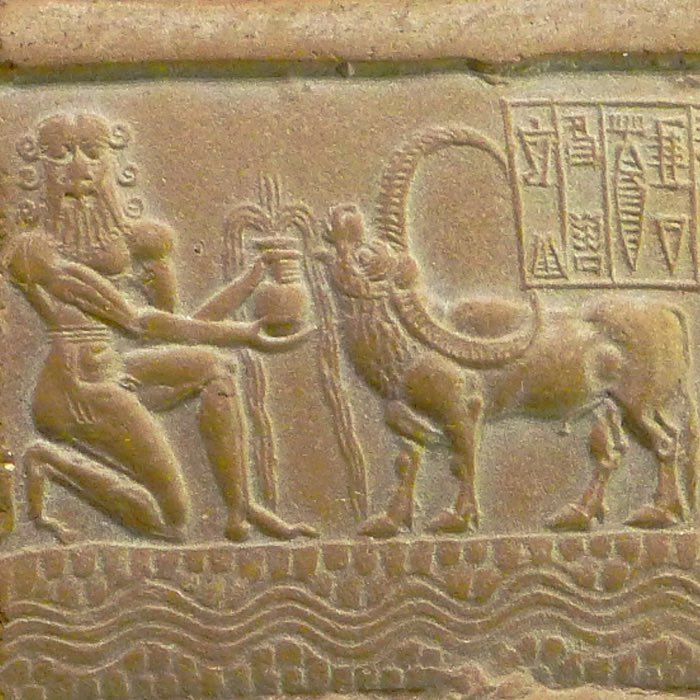

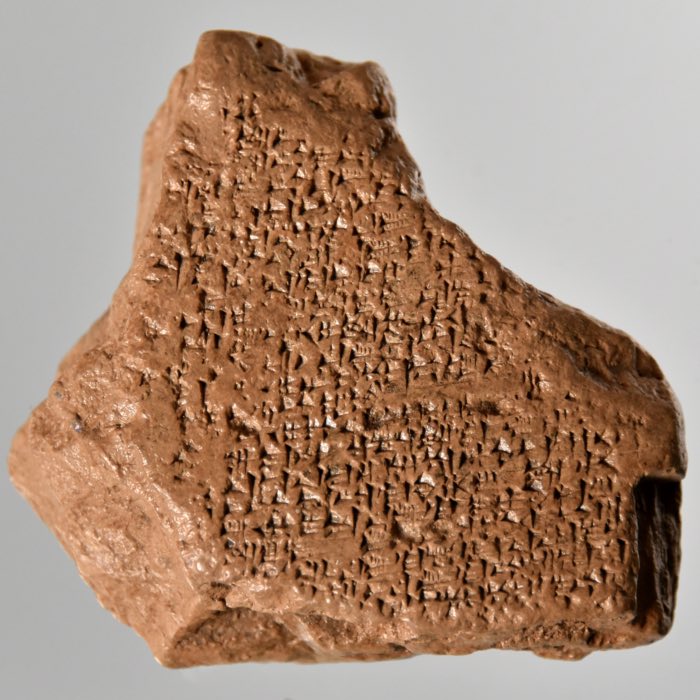

The Babylonian map of the world, from Sippar, Mesopotamia, 700-500 BCE. This partially broken clay tablet contains both cuneiform inscriptions and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. The more vertical lines indicate the Euphrates, and the triangles mountains at the world’s edge, including the Ararat, on which Utnapishtim Noah stranded (see Gilgamesh Epos). The small circles show city-states such as Uruk, and the belt the goodess salt sea serpent Tiamat. She, the Abzu and the Flood are probably sources of the Leviathan, a human-consuming cosmic sea monster. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Agricultural innovations: The basis of civilization

Agriculture was the backbone of Mesopotamian society, and its success hinged on the development of advanced techniques to manage the region’s challenging environment. Mesopotamian farmers faced the dual challenges of arid conditions and unpredictable flooding from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. To address these, they developed a sophisticated system of irrigation, which became a hallmark of their ingenuity.

Left: Hypothetical plan of a village’s hinterland in ancient lower Mesopotamia. The plan illustrates the careful organization of agricultural fields, irrigation canals, and residential areas, reflecting the importance of resource management and urban planning in early Mesopotamian societies. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Field of cereal near the Euphrates in the northwest of modern Iraq. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Irrigation involved the construction of canals, levees, and reservoirs to control and distribute water. These structures required collective labor and precise engineering, often coordinated by temple or palace authorities. Irrigation not only enabled the cultivation of staple crops such as barley, wheat, and dates but also supported the growth of surplus agricultural production, fueling urbanization and trade.

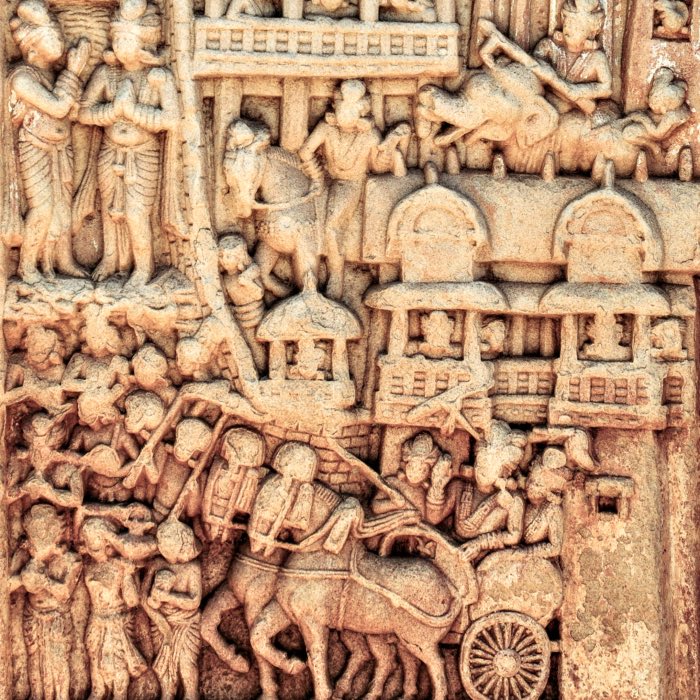

Left: Bas-relief from the palace of Tell Halaf, 9th century BCE, depicting a man slaughtering a sheep. Reliefs like this provide insights into the daily life and practices of ancient Mesopotamians, highlighting evidence of animal husbandry and offering a glimpse into the agricultural richness of the time. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Bronze statuette of a bull inlaid with silver, Early Dynastic Period III of Mesopotamia, 2900-2350 BCE, Louvre. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Mesopotamians were also among the first to experiment with crop rotation and soil management to maintain agricultural productivity. Clay tablets from the third millennium BCE provide detailed accounts of farming techniques, demonstrating an understanding of seasonal cycles and their impact on planting and harvesting.

Architecture and engineering: Mastery of materials and space

Mesopotamian architecture and engineering showcased remarkable adaptability and innovation, particularly in their use of available materials. The scarcity of stone and timber in southern Mesopotamia led to the widespread use of mudbrick, a versatile material suited to the region’s climate.

One of the most iconic architectural achievements of Mesopotamia is the ziggurat, a stepped temple structure that served as a religious and administrative center. Ziggurats, such as the Great Ziggurat of Ur, required meticulous planning and construction techniques, including the use of bitumen as a binding agent and waterproofing material.

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the ‘Anu Ziggurat’, dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BCE. The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BCE. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0); Bottom source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the ‘Anu Ziggurat’, dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BCE. The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BCE. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0); Bottom source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Beyond monumental architecture, the Mesopotamians excelled in urban planning. Cities like Uruk and Babylon featured organized street layouts, drainage systems, and public spaces, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of communal living. Canals and bridges facilitated trade and transportation, while walls and fortifications demonstrated their expertise in defensive engineering.

Mathematics: The foundation of quantitative knowledge

The Mesopotamians were pioneers in the field of mathematics, developing systems that laid the groundwork for future civilizations. Their numerical system was sexagesimal, or base-60, a choice that allowed for flexible division and multiplication. This system persists in modern measurements of time and angles.

Clay tablets from the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000–1600 BCE) reveal advanced mathematical practices, including the use of place value and the concept of zero. These texts demonstrate their ability to solve complex problems involving geometry, algebra, and ratios. For example, the Plimpton 322 tablet contains a list of Pythagorean triples, indicating an understanding of the relationship between the sides of right triangles long before Pythagoras.

The Plimpton 322 clay tablet, with numbers written in cuneiform script. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Plimpton 322 clay tablet, with numbers written in cuneiform script. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Mathematics was integral to Mesopotamian society, underpinning activities such as land surveying, tax calculation, and the construction of monumental structures. The precision of their calculations reflects a practical application of mathematical knowledge to real-world problems.

Left: A clay tablet, mathematical, geometric-algebraic, similar to the Euclidean geometry, from Shaduppum, Iraq, 2003–1595 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Clay tablet, mathematical, geometric-algebraic, similar to the Pythagorean theorem, from Tell al-Dhabba’i, Iraq, 2003–1595 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Astronomy: Mapping the heavens

The Mesopotamians’ interest in astronomy was deeply intertwined with their religious and practical concerns. They observed the movements of celestial bodies to create some of the earliest known calendars, enabling the prediction of seasonal changes and the timing of agricultural activities. The lunisolar calendar they developed consisted of 12 lunar months, with intercalary months added to synchronize with the solar year.

Star list with distance information, Uruk (today: Iraq), 320-150 BCE, the list gives each constellation, the number of stars and the distance information to the next constellation in ells. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

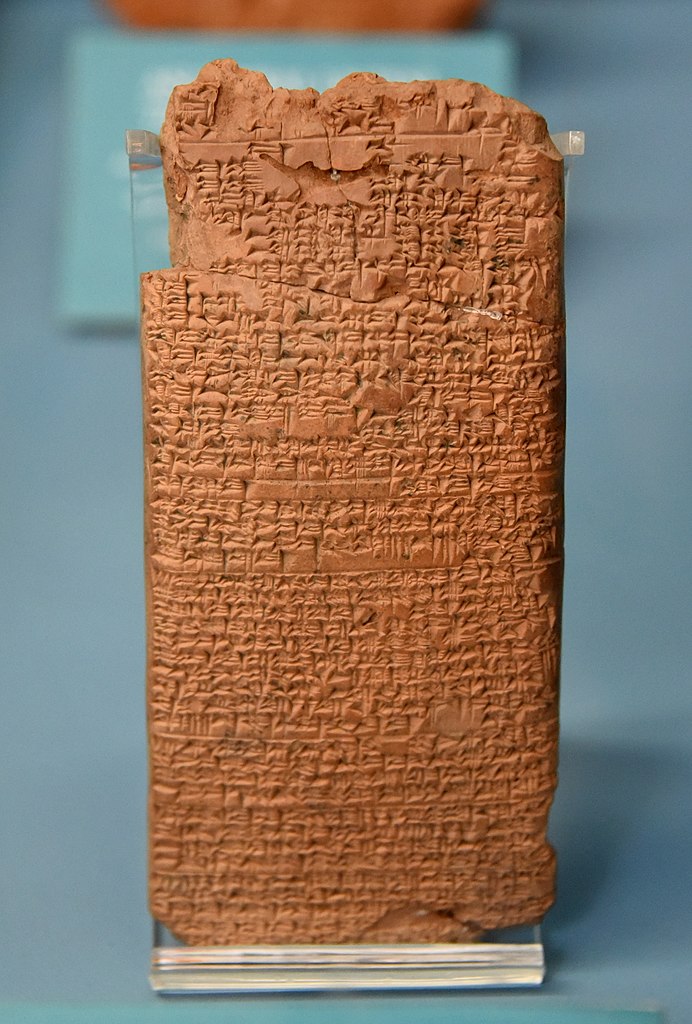

Astronomical knowledge was also used for divination, as celestial events were believed to reflect the will of the gods. Mesopotamian priests meticulously recorded astronomical observations, documenting phenomena such as eclipses, planetary movements, and the appearance of constellations. These records, preserved in texts such as the Mul.Apin, represent some of the earliest systematic studies of the heavens.

One of the Mul.apin cuneiform tablets. The tablets are a compendium that deals with many diverse aspects of Babylonian astronomy and astrology. For example, the Babylonian zodiac divides the sky into 12 zodiacal regions – a concept later adopted by the Greeks and Romans and still in use today. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The legacy of Mesopotamian astronomy is profound, influencing the later astronomical traditions of the Greeks, Persians, and Indians. Their division of the sky into 12 zodiacal regions and their methods of recording celestial events became integral to the development of astrological and scientific astronomy.

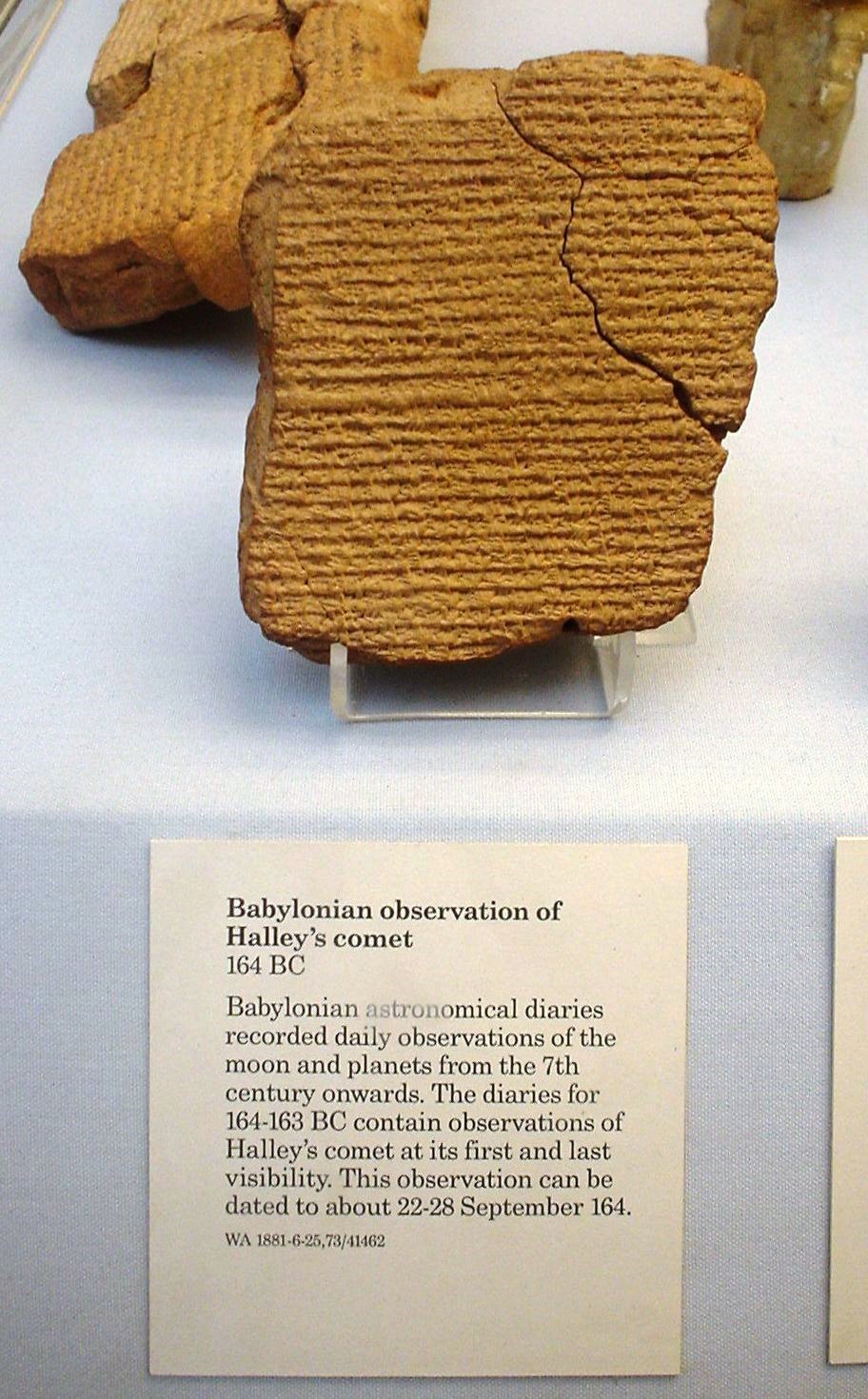

A Babylonian tablet recording Halley’s comet in 164 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Medicine: early practices of healing and diagnosis

Mesopotamian medicine combined empirical observation with spiritual practices, reflecting their holistic view of health and disease. Medical texts, such as those from the library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, contain detailed descriptions of symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments. These texts demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of anatomy and the effects of various ailments.

A medical recipe concerning poisoning. Terracotta tablet, from Nippur, Iraq. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Treatments often involved a combination of herbal remedies, surgical procedures, and incantations, underscoring the dual role of the physician as both healer and spiritual mediator. For example, texts describe the use of bandages, splints, and antiseptic treatments alongside prayers to specific gods associated with healing, such as Gula.

The Mesopotamians also recognized the importance of prognosis, classifying diseases based on their expected outcomes. This approach reflects an early understanding of pattern recognition and the systematic study of illness.

Writing and record-keeping: The technology of knowledge

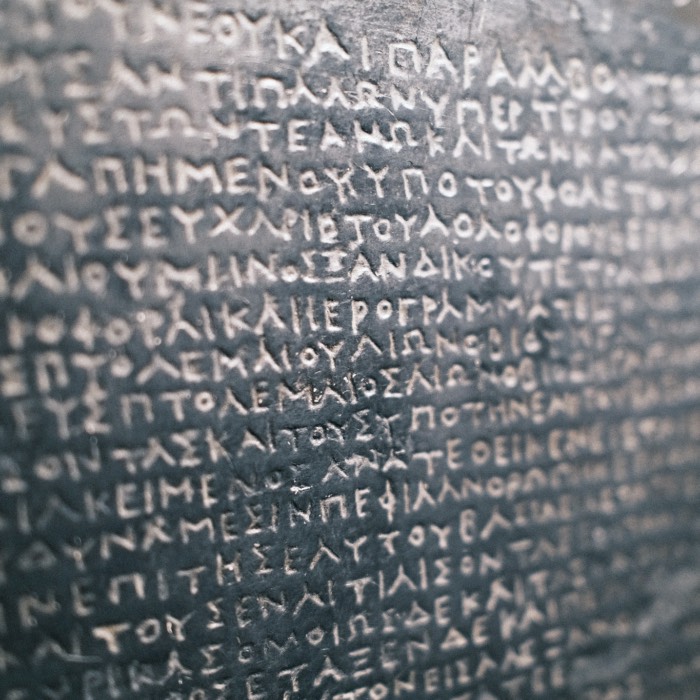

The development of cuneiform writing around 3100 BCE was one of Mesopotamia’s most transformative achievements. Initially used for administrative purposes, writing evolved into a tool for recording scientific, legal, and literary knowledge. Clay tablets served as durable records, preserving a vast corpus of information that provides insights into Mesopotamian techniques and sciences.

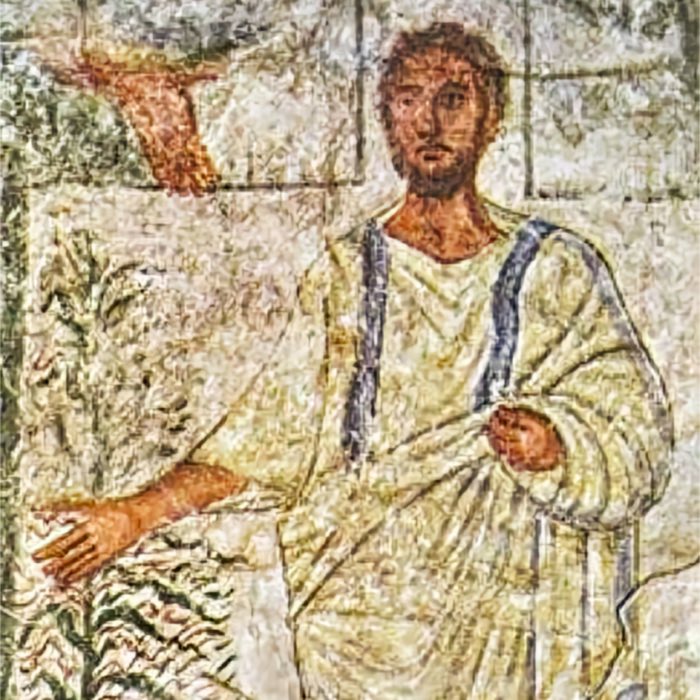

Code of Hammurabi on the stele, with a relief of Hammurabi receiving the laws from Shamash (or Marduk). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Administrative texts, such as those from the city of Uruk, detail the allocation of labor and resources, while legal codes, like the Code of Hammurabi, reflect an advanced understanding of societal organization. Literary works, including the Epic of Gilgamesh, showcase the interplay between science, religion, and culture.

One of the tablets of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

One of the tablets of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Legacy of Mesopotamian technologies and sciences

The techniques and sciences developed in Mesopotamia laid the foundation for subsequent civilizations in the ancient Near East and beyond. Their irrigation systems influenced agricultural practices across the region, while their mathematical and astronomical innovations informed Greek, Persian, and Indian scholarship. The integration of empirical observation with spiritual and cultural frameworks reflects a holistic approach to knowledge that continues to inspire contemporary studies of early science.

Mesopotamia’s achievements underscore the ingenuity and adaptability of early civilizations in addressing complex challenges. By harnessing their environment, organizing society, and systematizing knowledge, the Mesopotamians created a legacy that remains central to the history of human progress.

References and further reading

- Robson, E., Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History, 2008, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691091822

- A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia - Portrait Of A Dead Civilization, 1977, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 9780226631875

- Bottéro, J., Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, 1995, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226067278

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521533386

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, The Sumerian World, 2013, Routledge, ISBN: 9780415569675

- Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia - The invention of the city, 2001, Allan Lane, ISBN: 9780713991987

comments