The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh, widely regarded as the oldest surviving work of epic literature, stands as a monumental achievement of ancient Mesopotamian culture. Composed in the Sumerian and later Akkadian languages, the poem explores profound themes of friendship, mortality, and the human desire for meaning. Originating in the third millennium BCE and refined into a cohesive epic during the second millennium BCE, it tells the story of Gilgamesh, a historical king of Uruk, whose legendary exploits transcend his earthly reign to grapple with universal questions of existence.

Fragment of Tablet II of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq, Old-Babylonian period (2003-1595 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Fragment of Tablet II of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq, Old-Babylonian period (2003-1595 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Epic of Gilgamesh also contains a striking parallel to the biblical story of Noah and the Flood, as seen in its depiction of Utnapishtim, a character who survives a divine deluge. This shared narrative highlights the cultural and literary interplay between Mesopotamian mythology and later religious traditions, demonstrating how ancient stories evolved and were adapted across civilizations.

Historical and cultural context of the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is deeply rooted in the cultural and religious milieu of Mesopotamia. Gilgamesh, a semi-mythical king of Uruk who likely reigned during the early Dynastic Period (circa 2700 BCE), was venerated for his achievements in building and governance. Over time, his exploits were transformed into legendary tales, reflecting the Mesopotamian fascination with heroic figures who bridged the human and divine realms.

One of the tablets of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

One of the tablets of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

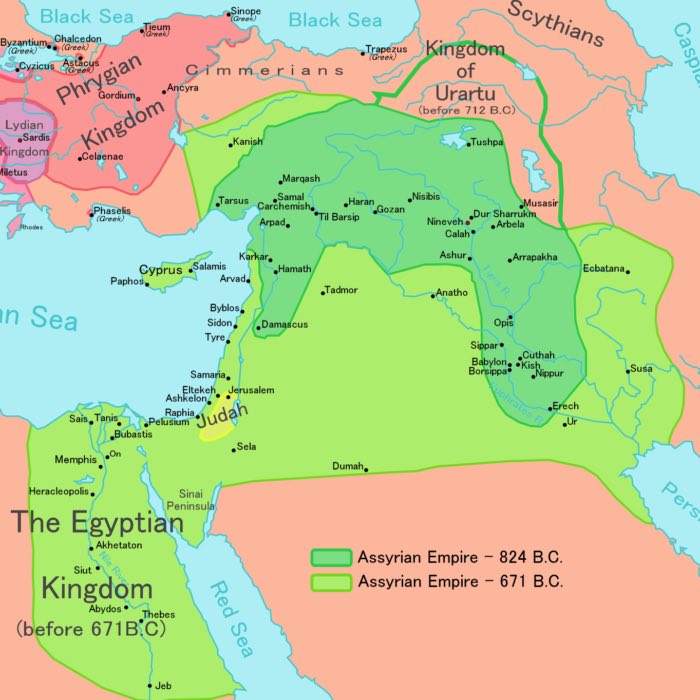

The epic in its final, standardized form, often referred to as the “Standard Babylonian Version”, was compiled by the scholar Sin-leqi-unninni around 1200 BCE. This version draws from older Sumerian texts, integrating their narratives into a unified work that reflects the values, concerns, and aspirations of Mesopotamian society. The text was widely disseminated, as evidenced by its discovery in libraries across the Near East, including the renowned Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

The narrative of the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh unfolds as a journey of transformation, beginning with Gilgamesh as an arrogant and oppressive king. His tyranny over the people of Uruk prompts the gods to create Enkidu, a wild man who becomes Gilgamesh’s equal and companion. Their initial confrontation evolves into a profound friendship, and together they embark on heroic quests, including the slaying of the monstrous Humbaba in the Cedar Forest and the killing of the Bull of Heaven.

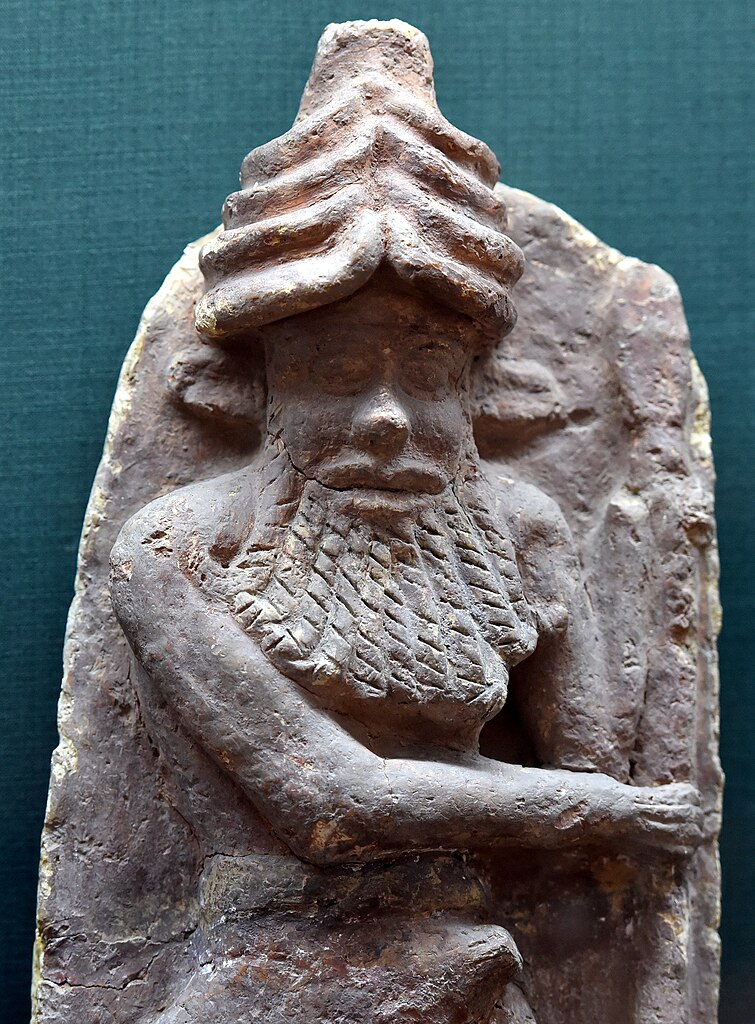

Left: Hero mastering a lion, 8th century BCE, palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II in Dur-Sharrukin, current Khorsabad in Iraq at the Louvre Museum. This ancient Assyrian statue possibly represents Gilgamesh. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Terracotta wall panel depicting Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s friend. He wears a horned helmet and his lower body is bull-like (not shown here). From Ur, Iraq. 2027-1763 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

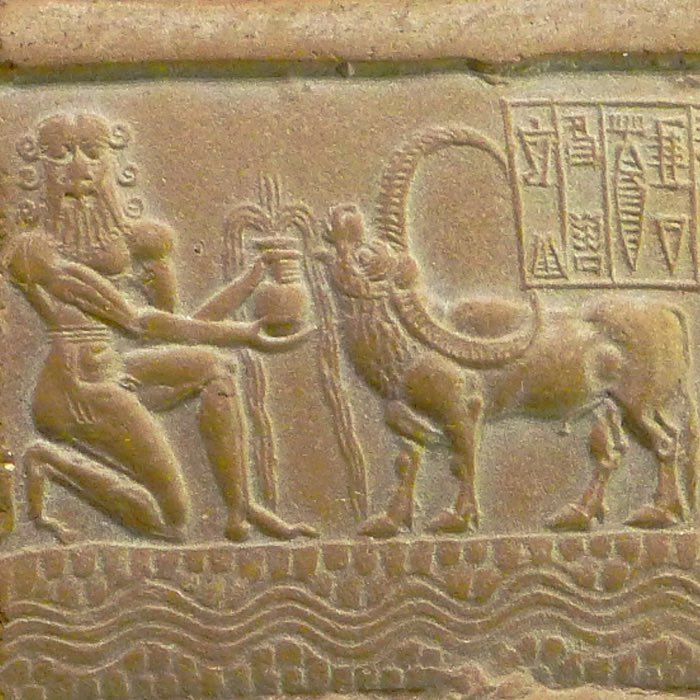

Tragedy strikes when the gods punish their hubris by decreeing Enkidu’s death. Enkidu’s demise plunges Gilgamesh into despair, forcing him to confront his own mortality. This existential crisis drives the second half of the epic, in which Gilgamesh seeks the secret of eternal life. His journey leads him to Utnapishtim, a man who has been granted immortality by the gods after surviving a great flood.

The Babylonian map of the world, from Sippar, Mesopotamia, 700-500 BCE. This partially broken clay tablet contains both cuneiform inscriptions and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. The more vertical lines indicate the Euphrates, and the triangles mountains at the world’s edge, including the Ararat, on which Utnapishtim Noah stranded. The small circles show city-states such as Uruk, and the belt the goodess salt sea serpent Tiamat. She, the Abzu and the Flood are probably sources of the Leviathan, a human-consuming cosmic sea monster. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Utnapishtim recounts the story of the deluge, explaining how he was instructed by the god Ea to build a boat and preserve life during the cataclysm. Despite his best efforts to gain immortality, Gilgamesh ultimately fails, returning to Uruk with a newfound acceptance of his human limitations and a recognition of the enduring legacy he can achieve through his works and his city.

The Sumerian Genesis describes the Abzu as a cosmic freshwater ocean surrounding our planet created in its midst, so the sketch shows the same as Babylon’s map, now in sideview. A breathable bubble of air clings to earth’s surface; the mountains of Lebanon and Zagros serve as pillars of the freshwater sky; and the tunnel enables the sun god to rush at night from west to east. There, close to sunrise and Siduris pub, lies Dilmun, Utnahpishtim’s island, where Gilgamesh dived into the depths, founding the herb of eternal life. The sluice gates set into sky are an important detail: through them, the gods with their skills at building irrigation systems were able to fertilise Mesopotamia with rain, but also to unleash the great flood. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Sumerian Genesis describes the Abzu as a cosmic freshwater ocean surrounding our planet created in its midst, so the sketch shows the same as Babylon’s map, now in sideview. A breathable bubble of air clings to earth’s surface; the mountains of Lebanon and Zagros serve as pillars of the freshwater sky; and the tunnel enables the sun god to rush at night from west to east. There, close to sunrise and Siduris pub, lies Dilmun, Utnahpishtim’s island, where Gilgamesh dived into the depths, founding the herb of eternal life. The sluice gates set into sky are an important detail: through them, the gods with their skills at building irrigation systems were able to fertilise Mesopotamia with rain, but also to unleash the great flood. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Ancient Mesopotamian terracotta relief showing Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven, which Anu gives to his daughter Ishtar in Tablet IV of the Epic of Gilgamesh after Gilgamesh spurns her amorous advances. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Themes and symbolism in the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a profound exploration of universal human concerns. At its core, it grapples with the transient nature of life and the pursuit of meaning in the face of mortality. Gilgamesh’s journey reflects a transformation from hubris to humility, as he learns that true immortality lies not in escaping death but in leaving a lasting impact through one’s deeds and creations.

Friendship is another central theme, as the bond between Gilgamesh and Enkidu humanizes the otherwise divine-like king. Their relationship emphasizes the importance of companionship, loyalty, and shared experience in navigating life’s challenges.

The story of the flood, recounted by Utnapishtim, serves as a pivotal moment in the epic. It encapsulates the Mesopotamian worldview, in which divine judgment and favor are integral to human existence. The flood narrative also highlights the fragility of human life and the necessity of divine intervention for survival.

The flood narrative: Parallels with the story of Noah

The flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh bears remarkable similarities to the biblical account of Noah in the Book of Genesis. Both narratives describe a divine decision to destroy humanity due to its wickedness, the selection of a righteous individual to preserve life, and the construction of a boat to withstand the deluge. In both stories, the survivors release birds to determine whether the floodwaters have receded, and both end with a divine covenant or blessing.

Noah’s Ark (1846), by the American folk painter Edward Hicks. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Noah’s Ark (1846), by the American folk painter Edward Hicks. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

These parallels suggest that the Genesis account may have been influenced by earlier Mesopotamian traditions, particularly the Epic of Gilgamesh and the older Sumerian tale of Ziusudra. The transfer of this narrative likely occurred through cultural exchange and interaction between Mesopotamian and Levantine societies during the second millennium BCE.

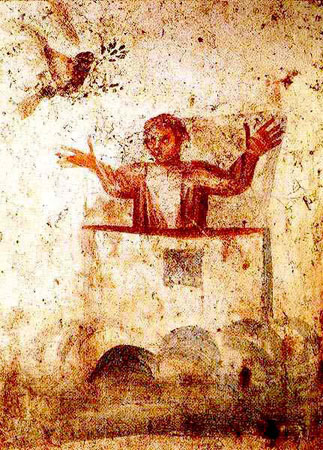

Left: A Jewish depiction of Noah, depicting Noah’s ark landing on the ‘mountains of Ararat’. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: An early Christian depiction showing Noah giving the gesture of orant as the dove returns. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Despite their similarities, the two stories also reflect distinct theological perspectives. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the flood highlights the capriciousness of the gods and the precariousness of human existence. In contrast, the Genesis account emphasizes the moral and covenantal relationship between humanity and a singular, omnipotent deity.

Legacy and influence of the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is not only a literary masterpiece but also a foundational text in the history of human storytelling. Its exploration of existential themes, coupled with its rich symbolism and intricate narrative structure, has influenced countless works of literature and philosophy.

The epic’s rediscovery in the 19th century had a profound impact on the study of ancient Near Eastern cultures and their influence on Western traditions. Its flood narrative, in particular, has sparked debates about the origins and dissemination of shared mythological motifs, highlighting the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations.

In contemporary times, the Epic of Gilgamesh continues to resonate as a timeless exploration of human aspirations and limitations. It serves as a reminder of our shared humanity and the enduring quest for meaning in a transient world.

Conclusion

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a testament to the intellectual and spiritual depth of Mesopotamian civilization. Through its narrative, rich symbolism, and profound themes, it addresses fundamental questions about life, death, and the human condition that remain relevant today. Its parallels with the story of Noah underscore the interconnectedness of ancient cultures and the enduring of myth to transcend boundaries of time and place.

References and further reading

- Dalley, S., Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199538362

- George, A. R., The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, 2003, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198149224

- Heidel, A., The Babylonian Genesis: The Story of Creation, 1963, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226323992

- Foster, B. R., The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation, Analogues, Criticism, 2001, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN: 978-0393975161

- Bottéro, J., Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, 1995, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226067278

comments