The Akkadian Empire: The first unified empire in history

The Akkadian Empire, founded by Sargon of Akkad around 2334 BCE, represents a transformative epoch in human history. It is often celebrated as the first empire to unify diverse peoples and territories under a centralized authority. Spanning large swathes of Mesopotamia and extending its influence into surrounding regions, the Akkadian Empire established new paradigms in governance, culture, and military strategy. Its achievements and challenges laid the foundations for future empires in the ancient Near East and beyond.

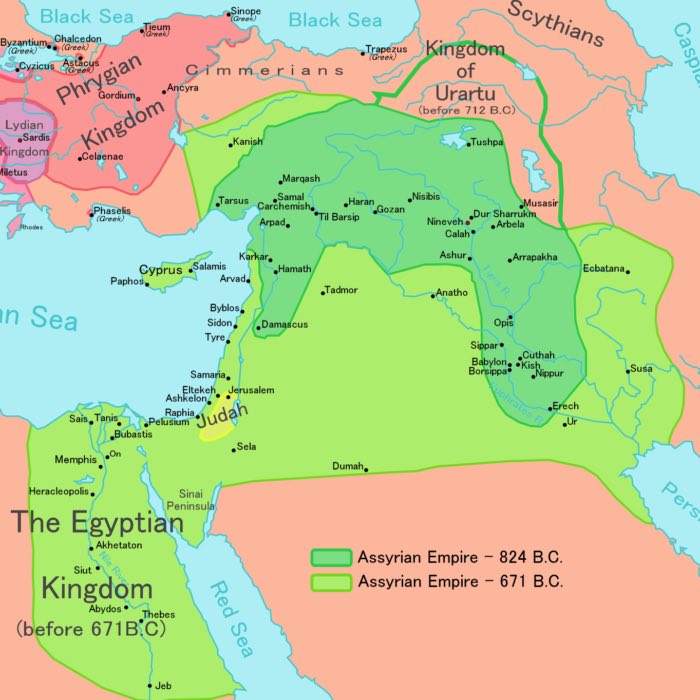

Map of the Akkadian Empire (brown) and the directions in which military campaigns were conducted (yellow arrows). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical and geographical context

Before the rise of Akkad, Mesopotamia was a mosaic of independent city-states, such as Uruk, Ur, and Lagash. These city-states, though culturally interconnected, were often embroiled in territorial disputes and competition for resources. The Sumerians, who dominated southern Mesopotamia, had made significant advancements in writing, religion, and governance, but their fragmented political structure limited large-scale unification.

Akkad before expansion (in green). The territory of Sumer under its last king Lugal-Zage-Si appears in orange. Circa 2350 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Akkadian Empire emerged in this context, unifying the city-states of Sumer under a centralized government for the first time. Geographically, the empire extended from the Persian Gulf in the south to parts of modern-day Syria and Anatolia in the north and west, encompassing both the fertile alluvial plains of southern Mesopotamia and the more arid and resource-rich northern regions.

The rise of Sargon and the formation of the empire

The founder of the Akkadian Empire, Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2334–2279 BCE), rose from humble origins. According to later legends, he was a cupbearer to the king of Kish before seizing power and embarking on a campaign of conquest. Sargon established Akkad (or Agade) as his capital, though its precise location remains uncertain.

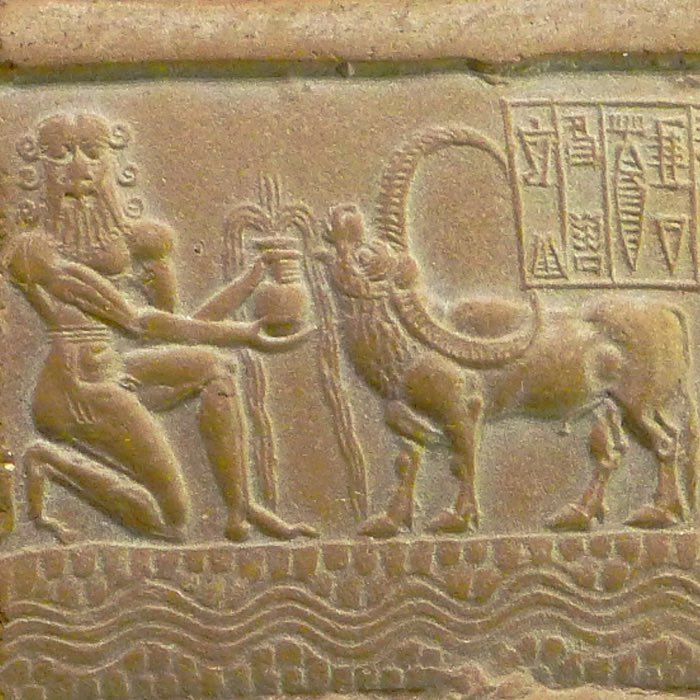

Sargon on his victory stele, with a royal hair bun, holding a mace and wearing a flounced royal coat on his left shoulder with a large belt (left), followed by an attendant holding a royal umbrella. The name of Sargon in cuneiform (“King Sargon”) appears faintly in front of his face. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

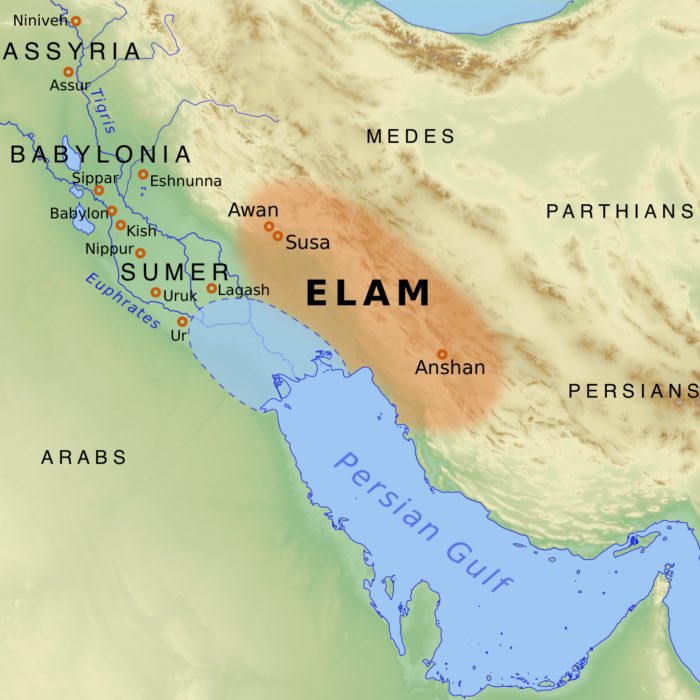

Sargon’s military campaigns were instrumental in the empire’s formation. He is credited with conquering key Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, and Lagash and extending Akkadian influence into Elam (modern-day southwestern Iran) and the northern Levant. Sargon’s ability to integrate these diverse regions under a centralized administration marked a significant departure from the fragmented political landscape of the Sumerians.

Left: Prisoners escorted by a soldier, on a victory stele of Sargon of Akkad, circa 2300 BCE. The hairstyle of the prisoners (curly hair on top and short hair on the sides) is characteristic of Sumerians, as also seen on the Standard of Ur. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Akkadian official in the retinue of Sargon of Akkad, holding an axe. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Administrative and cultural achievements

The Akkadian Empire introduced innovative administrative practices that enabled the effective governance of a vast and diverse territory. Sargon appointed trusted officials, often members of his family, to govern distant provinces, ensuring loyalty to the central authority. This system of provincial administration provided a blueprint for later empires in the region, including Babylon and Assyria.

One of the most notable aspects of Akkadian governance was the promotion of the Akkadian language. Previously, Sumerian had been the dominant language of administration and culture. The Akkadians, however, adopted their Semitic tongue as the lingua franca of the empire, using it alongside Sumerian in official documents. This linguistic policy not only facilitated communication across the empire but also marked the beginning of a cultural synthesis between Sumerian and Akkadian traditions.

Art and literature flourished under the Akkadian Empire. Monumental works, such as the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, exemplify the empire’s artistic achievements and its emphasis on royal power. The stele depicts Naram-Sin, Sargon’s grandson, as a godlike figure triumphing over his enemies, symbolizing the divine legitimacy of Akkadian rule. Akkadian literature also included royal inscriptions and mythological texts that blended Sumerian and Akkadian elements, reflecting the cultural integration of the empire.

Military prowess and challenges

The Akkadian Empire’s expansion and maintenance were underpinned by its military strength. Sargon and his successors deployed well-organized and disciplined armies, equipped with advanced weaponry such as composite bows and copper weapons. The empire also utilized innovative siege tactics, enabling the conquest of fortified cities.

Akkadian soldiers slaying enemies, circa 2300 BCE, possibly from a Victory Stele of Rimush. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

However, the empire faced significant challenges, particularly from external threats. The Gutians, a group of mountain people from the Zagros region, repeatedly raided Akkadian territories, destabilizing the empire. Internal dissent and economic strain further compounded these difficulties, as the vastness of the empire made it difficult to maintain cohesion and control.

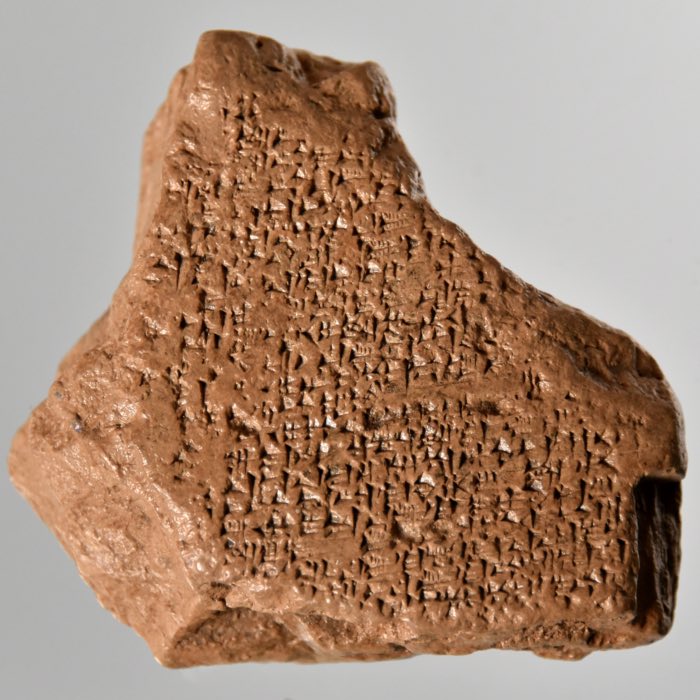

Treaty of alliance concluded between Naram-Sin of Akkad and Khita (?), a prince of Awan; Elamite language written in Akkadian script. Clay, ca. 2250 BCE. From Susa, Iran. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

The reign of Naram-Sin and the apex of Akkadian power

Naram-Sin (ca. 2254–2218 BCE), Sargon’s grandson, presided over the empire’s zenith. His military campaigns extended Akkadian influence to new heights, including victories in the Zagros Mountains and Anatolia. Naram-Sin’s declaration of himself as a god, a departure from the traditional Mesopotamian view of kingship, marked a significant moment in the conceptualization of royal authority. This act of self-deification, however, provoked both admiration and controversy, as it challenged long-standing religious norms.

Palace of Naram-Sin at Tell Brak. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Naram-Sin’s reign is also notable for its artistic achievements, such as the aforementioned Victory Stele, which immortalized his divine kingship and military triumphs. His efforts to fortify and centralize the empire exemplify the Akkadian rulers’ vision of creating a stable and enduring state.

Naked captives, on the Nasiriyah stele of Naram-Sin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Bassetki statue, another example of Akkadian artistic realism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Decline and legacy

The Akkadian Empire began to decline shortly after Naram-Sin’s reign, beset by a combination of internal and external factors. The Gutian incursions continued to weaken the empire, while economic difficulties and environmental challenges, such as droughts, exacerbated its instability. By the early 22nd century BCE, the empire had fragmented, and Mesopotamia returned to a landscape of competing city-states.

This bronze head traditionally attributed to Sargon is now thought to actually belong to his grandson Naram-Sin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Despite its relatively short duration, the Akkadian Empire left an enduring legacy. It established the concept of empire as a political and cultural entity, influencing later civilizations such as Babylon and Assyria. The Akkadians’ integration of diverse cultures and their administrative innovations provided a model for governance that resonated throughout the ancient Near East. Moreover, the Akkadian language continued to serve as a diplomatic and scholarly lingua franca for centuries, underscoring the cultural significance of Sargon’s empire.

Copy of an inscription of Naram-Sin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Conclusion

The Akkadian Empire stands as a landmark in human history, representing the first attempt to unify a vast and diverse territory under centralized rule. Its achievements in administration, language, art, and culture set the stage for the empires that followed, while its challenges and eventual decline highlight the complexities of maintaining imperial power. By examining the Akkadian Empire, we gain insight into the dynamics of early state formation and the enduring impact of one of humanity’s first great civilizations.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on the Akkadian Empireꜛ

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC, 2024, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 9781394210220

- Foster, B. R., The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia, 2015, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1138909755

- Roaf, M., Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, 1990, Facts on File, ISBN: 978-0816022182

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521533386

- Harriet E. W. Crawford, The Sumerian World, 2013, Routledge, ISBN: 9780415569675

- Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia - The invention of the city, 2001, Allan Lane, ISBN: 9780713991987

comments