The Japanese language and writing systems: Origins of a unique linguistic heritage

The Japanese language holds a unique place in the world’s linguistic and cultural heritage. Renowned for its complex writing system and intricate grammar, Japanese remains a subject of fascination for linguists and historians alike. Despite extensive research, the origins of Japanese are still a matter of debate, with competing theories pointing to influences from Austro-Tai, Altaic, and other linguistic families. Additionally, its writing system, characterized by a combination of three distinct scripts, is unparalleled in its structure and evolution. In this post, we explore the origins, development, and characteristics of the Japanese language and its writing systems.

The kanji for “Japanese” (read nihongo). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Origins of the Japanese language

Unlike other languages with clear genetic affiliations such as Indo-European or Sino-Tibetan, the Japanese language is a linguistic enigma, characterized by its unique structure and lack of clear genetic affiliation. While its precise origins remain uncertain, several theories have been proposed to explain its development and relationship to other languages.

Prehistoric roots

The precise origins of the Japanese language remain elusive, but its development is closely tied to the early inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Jōmon people, who inhabited the region from around 14,000 BCE to 300 BCE, spoke an unknown language that may have influenced early Japanese. Linguistic shifts occurred during the Yayoi period (900 BCE–300 CE), when migrants from the Korean Peninsula introduced new cultural and linguistic elements, including agriculture and metallurgy.

Reconstruction of Jōmon period houses in the Aomori Prefecture, Japan. It shares cultural similarities with settlements of Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula, as well as with later Japanese culture. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Reconstructed Yayoi-style dwellings at Yoshinogari. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Northern Kyushu is the part of Japan closest to the Asian mainland. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Language family and theoretical links

Japanese is classified as a language isolate, meaning it has no conclusively proven genetic relationship with other languages. However, several hypotheses have been proposed to explain its origins:

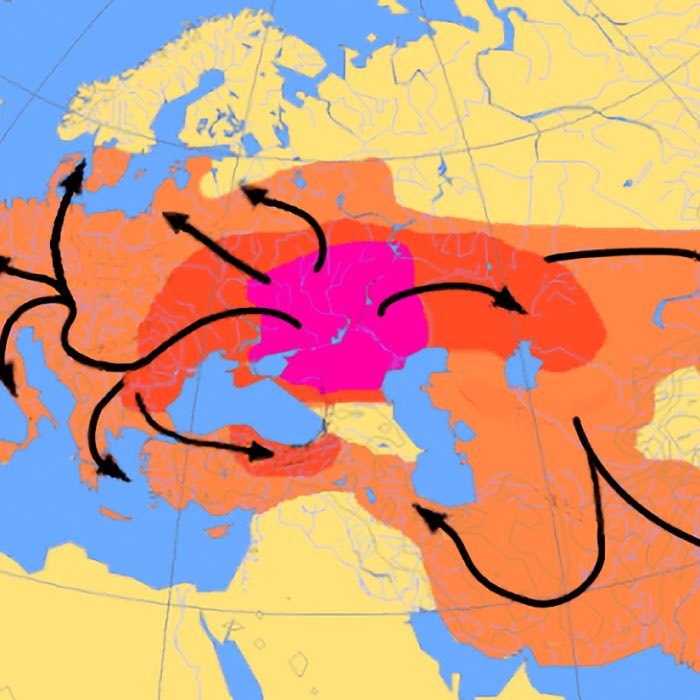

Altaic hypothesis

This theory suggests that Japanese is related to the Altaic language family, which includes Korean, Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic languages. Shared features, such as subject-object-verb word order and agglutinative morphology, support this view, though it remains controversial.

The branches of the Altaic language family: Blue: Turkic languages, Green: Mongolic languages, Red: Tungusic languages, Yellow: Koreanic languages, Purple: Japonic languages, Brown: Ainu languages. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The branches of the Altaic language family: Blue: Turkic languages, Green: Mongolic languages, Red: Tungusic languages, Yellow: Koreanic languages, Purple: Japonic languages, Brown: Ainu languages. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Austro-Tai and Austronesian influence

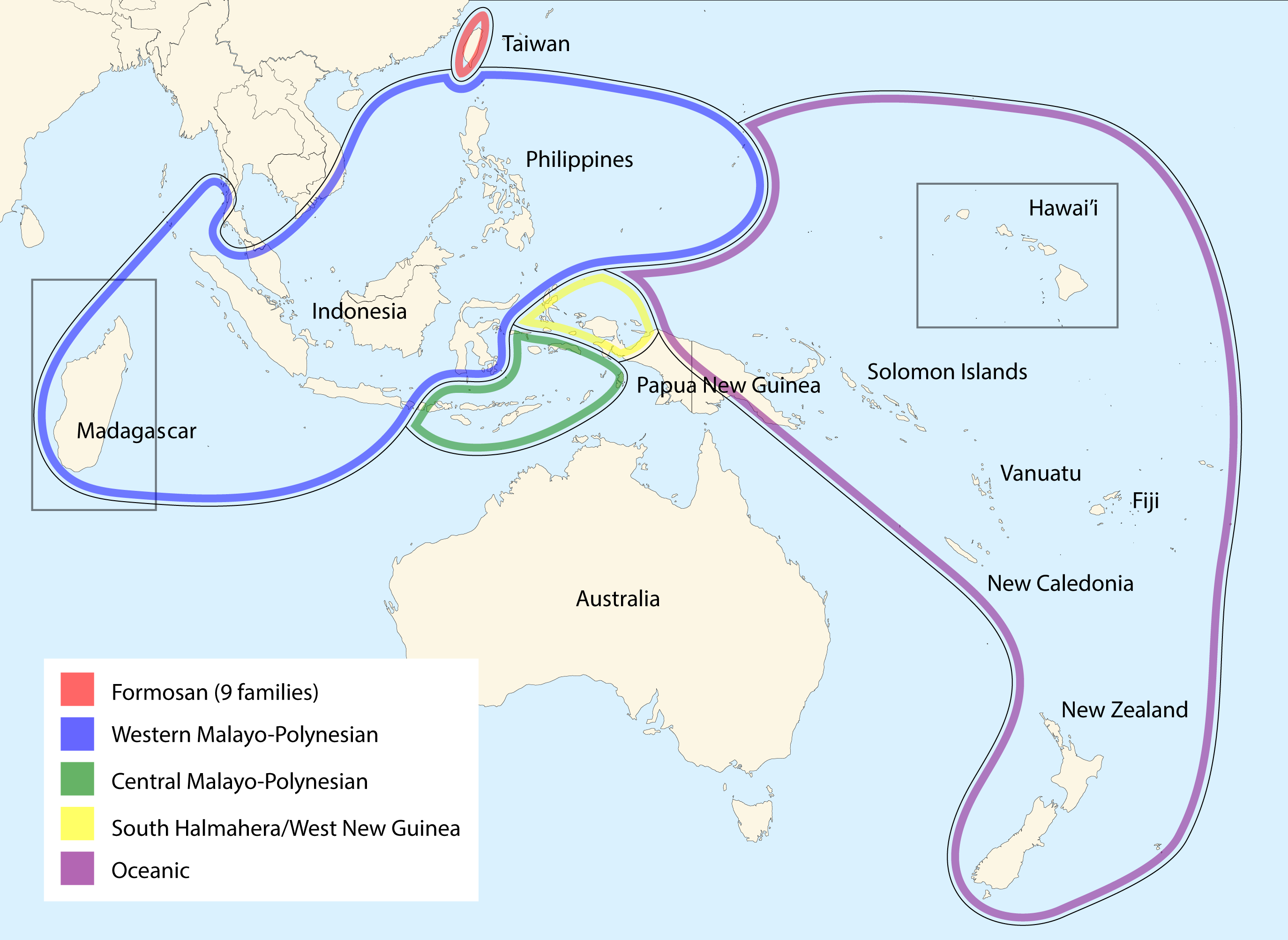

Some linguists argue for a distant connection between Japanese and Austronesian languages, based on similarities in phonology and certain grammatical markers. Early contact with Austronesian-speaking peoples during the Jōmon period may have introduced these elements.

The historical distribution of Austronesian languages. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). Bottom source after Blust (1999): Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The historical distribution of Austronesian languages. Top source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). Bottom source after Blust (1999): Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Austro-Tai languages are a proposed language family that comprises the Austronesian languages and Kra–Dai languages. The map shows Tai-Kadai migration route according to Matthias Gerner’s Northeast to Southwest Hypothesis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Austro-Tai languages are a proposed language family that comprises the Austronesian languages and Kra–Dai languages. The map shows Tai-Kadai migration route according to Matthias Gerner’s Northeast to Southwest Hypothesis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Korean influence

The relationship between Japanese and Korean is a topic of intense study. While the two languages share structural similarities, such as agglutination and honorifics, most scholars attribute these to contact rather than a direct genetic link.

Left: Current extent of Koreanic as majority and minority (dashed) languages in East Asia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0). – Right: Dialects of the Korean language. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Despite these theories, Japanese’s origins remain uncertain, highlighting its status as a linguistic enigma.

Old Japanese

The earliest written records of Japanese date to the 8th century CE, during the Nara period (710–794 CE). Old Japanese, preserved in texts such as the Kojiki (古事記, Records of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Man’yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), exhibits a phonological system distinct from modern Japanese. It lacked modern pitch accent and featured sounds and grammatical forms no longer in use. Old Japanese also displayed evidence of influence from Classical Chinese, introduced through trade and political contact.

Development and characteristics of Japanese

Japanese has evolved over centuries, absorbing influences from neighboring cultures and adapting to changing social and political contexts. Its linguistic features reflect this complex history, shaping its phonology, syntax, and writing systems.

Phonology and syntax

Japanese is an agglutinative language, meaning it forms words and grammatical structures by adding affixes to base stems. Its phonetic inventory is relatively simple, with five vowel sounds (a, i, u, e, o) and a limited set of consonants. Syllables are typically structured as consonant-vowel pairs, contributing to its rhythmic and melodic quality.

The syntax of Japanese follows a subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, a feature it shares with Korean and other Altaic languages. This structure influences sentence formation, with verbs and grammatical markers appearing at the end of clauses.

The following table provides examples of common Japanese words, their pronunciation, and their meanings:

| Japanese word | Pronunciation (Romaji) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| たべる | taberu | to eat |

| はなす | hanasu | to speak |

| あい | ai | love |

| さん | san | Mr./Ms. |

| さくら | sakura | cherry blossom |

| こんにちは | konnichiwa | hello |

| すし | sushi | sushi |

| みず | mizu | water |

Honorifics and politeness

One of the defining features of Japanese is its system of honorifics (keigo), which reflects social hierarchies and interpersonal relationships. Honorifics modify verbs, nouns, and pronouns to indicate respect, humility, or formality. This system underscores the importance of social context and has deeply influenced Japanese culture and communication.

Honorifics in Japanese are expressed through various linguistic forms, including:

- Respectful language (Sonkeigo): Used to elevate the listener or third party, often modifying verbs or expressions. Example: 行く (iku, “to go”) → いらっしゃる (irassharu, “to go/honorific”).

- Humble language (Kenjougo): Used to lower the speaker’s status to show humility toward the listener or third party. Example: 行く (iku, “to go”) → 参る (mairu, “to go/humble”).

- Polite language (Teineigo): Indicates politeness without showing hierarchy; commonly used in formal or neutral situations. Example: 行く (iku, “to go”) → 行きます (ikimasu, “to go/polite”).

- Honorific prefixes: Prefixes like お- (o-) or ご- (go-) are added to words to show politeness or respect. Example: お名前 (onamae, “name [polite]””), ご案内 (goannai, “guidance [polite]””).

- Titles and suffixes: Attached to names to indicate social relationships and formality. Examples: さん (san, “Mr./Ms.””), さま (sama, “formal Mr./Ms.”), ちゃん (chan,”affectionate suffix”).

The following table illustrates the use of honorifics in Japanese, demonstrating how verbs and nouns change based on the level of politeness and respect:

| Meaning | Basic form | Sonkeigo | Kenjougo | Teineigo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | 人 hito | 方 kata | 者 mono | |

| company | 会社 kaisha | 御社 onsha | 弊社 heisha | |

| wife | 女房 nyōbō | 奥さま oku-sama | 妻 tsuma | |

| to eat | 食べる taberu | 召しあがる meshi-agaru | 頂く itadaku | |

| to drink | 飲む nomu | 召しあがる meshi-agaru | 頂戴する chōdai suru | |

| to be | いる iru | いらっしゃる irassharu | おる oru | |

| to be / to have | ある aru | おありである o ari de aru | ござる gozaru | |

| to get | もらう morau | 頂く itadaku | ||

| to do | する suru | なさる nasaru | 致す itasu | 致す itasu |

| to read | 読む yomu | 御覧になる goran ni naru | 拝見する haiken suru | |

| to see | 見る miru | 御覧になる goran ni naru | 拝見する haiken suru | |

| to hear | 聞く kiku | 伺う ukagau | ||

| to come / to go | 来る kuru / 行く iku | いらっしゃる irassharu | 参る mairu | 参る mairu |

Modern Japanese and dialects

Modern Japanese, or Nihongo, emerged during the Edo period (1603–1868) as a standardized form of the language. It is based primarily on the Tokyo dialect, which was adopted as the national standard during the Meiji era (1868–1912). Despite this standardization, Japanese retains significant dialectal diversity, with regional variations in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. Notable dialects include Kansai-ben, spoken in the Osaka-Kyoto region, and Okinawan, which is part of the Ryukyuan language group.

Map of Japanese dialects and Japonic languages (without Ryukyuan islands). Blue: Tokyo accent (standard accent pattern), orange: Kyōto-Ōsaka accent, white: no accent. Descriptions are in German. At the time I wrote this post, there was no English version available. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5).

Map of Japanese dialects and Japonic languages (without Ryukyuan islands). Blue: Tokyo accent (standard accent pattern), orange: Kyōto-Ōsaka accent, white: no accent. Descriptions are in German. At the time I wrote this post, there was no English version available. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5).

Map of Ryukyuan languages (the Ryukyuan islands are in the south of Japan). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Map of Ryukyuan languages (the Ryukyuan islands are in the south of Japan). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Writing Systems of Japanese

Historical Context

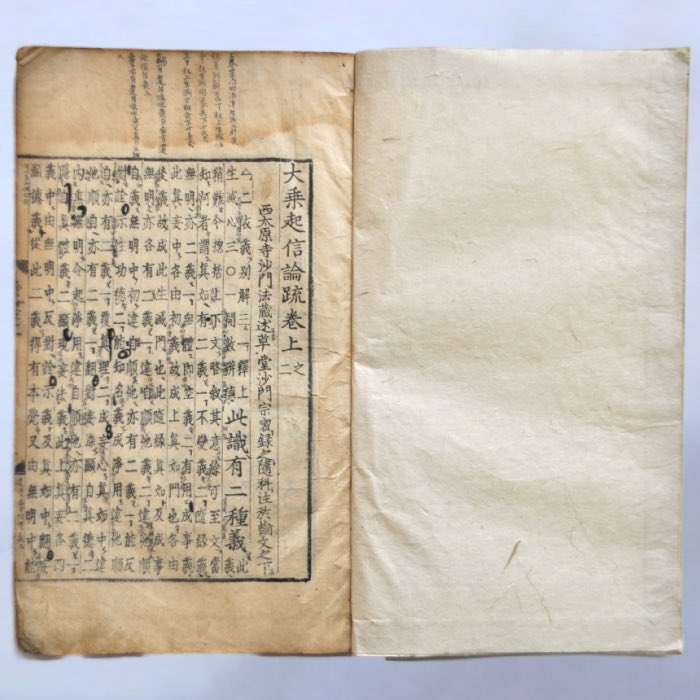

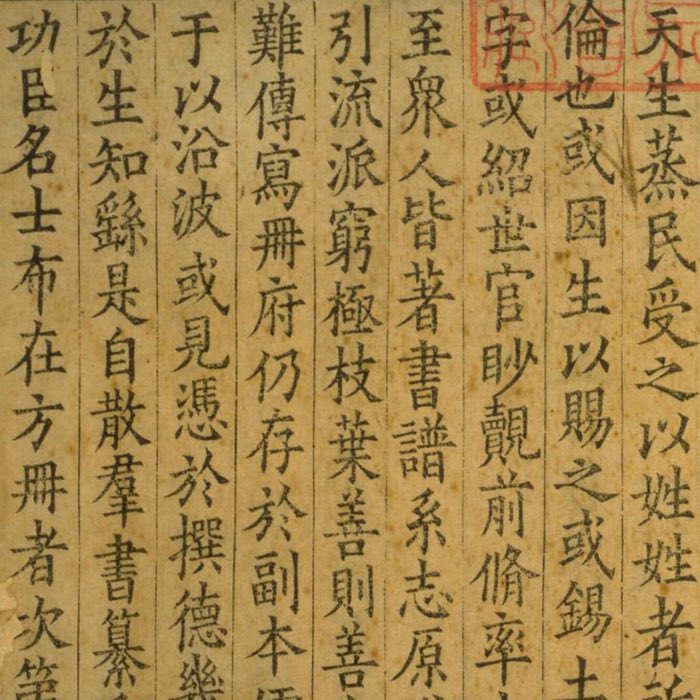

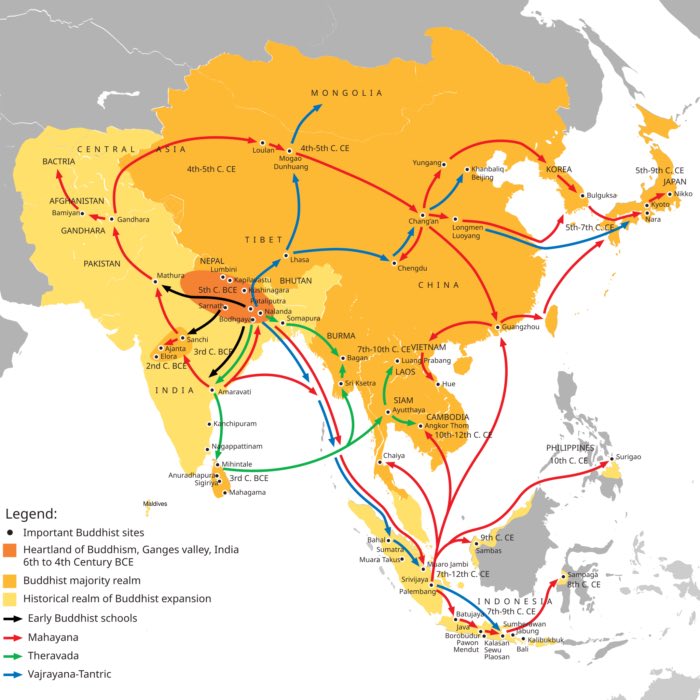

The Japanese writing system developed through interaction with Chinese culture, which introduced the use of Chinese characters (kanji) to Japan around the 5th century CE. Initially used for official documents and religious texts, kanji were gradually adapted to fit the Japanese language, resulting in the creation of two additional scripts: hiragana and katakana. These scripts, along with kanji, form the foundation of modern Japanese writing.

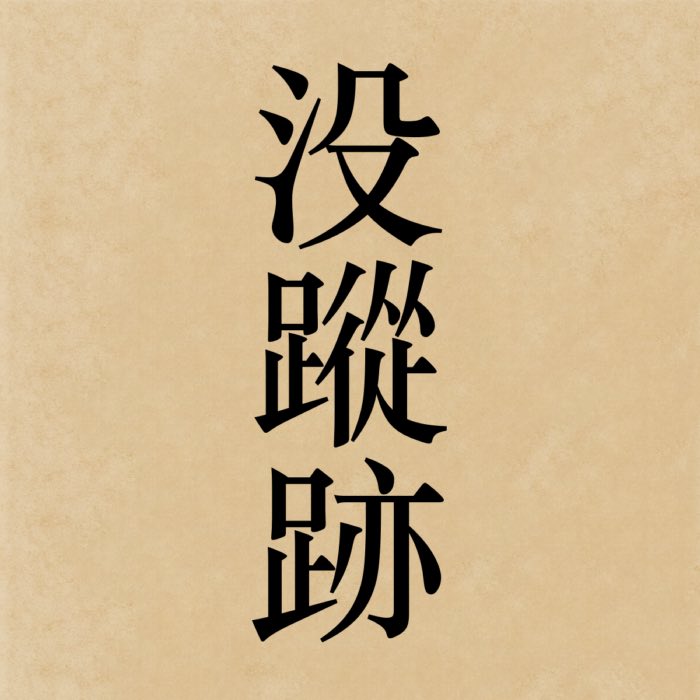

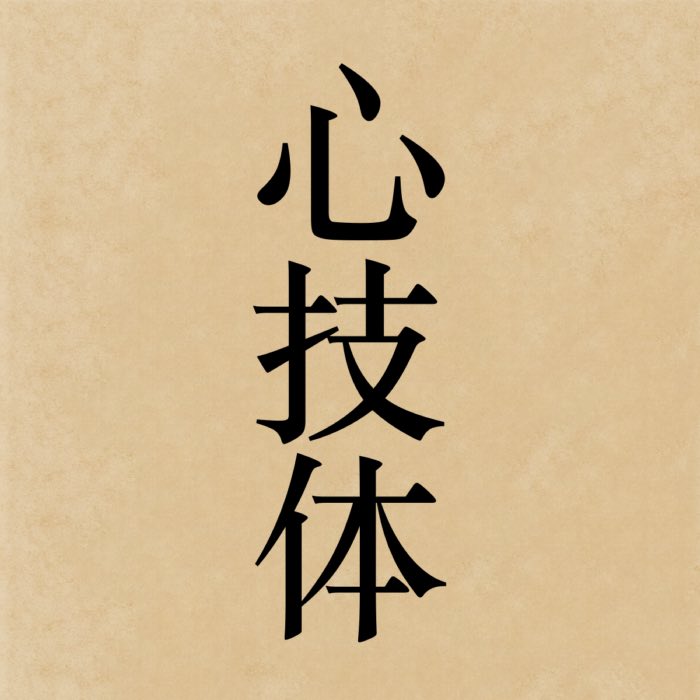

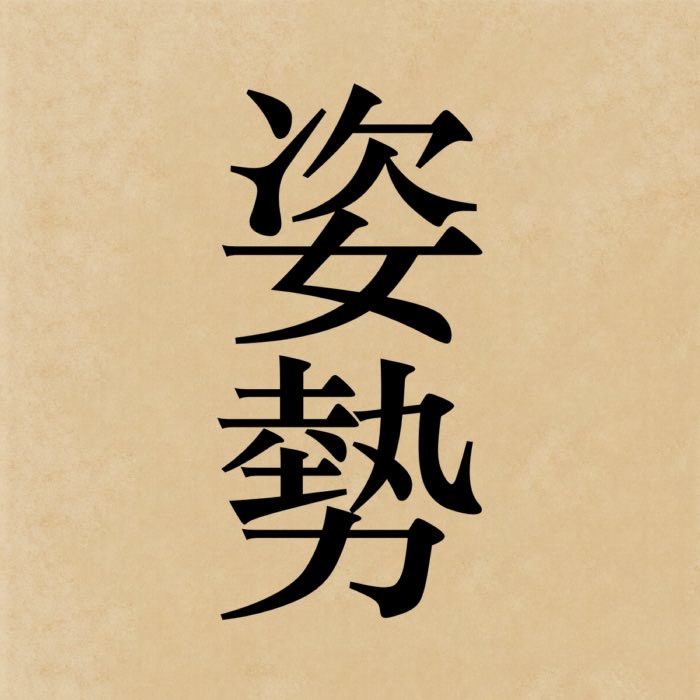

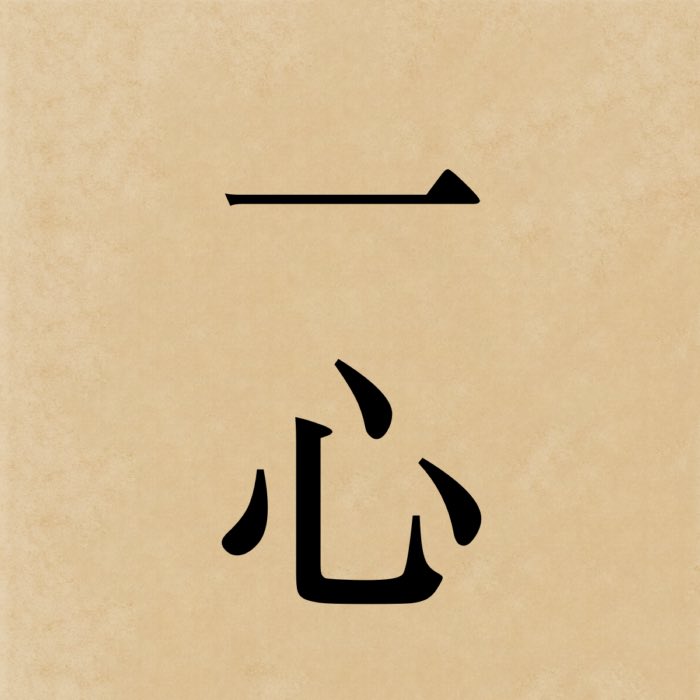

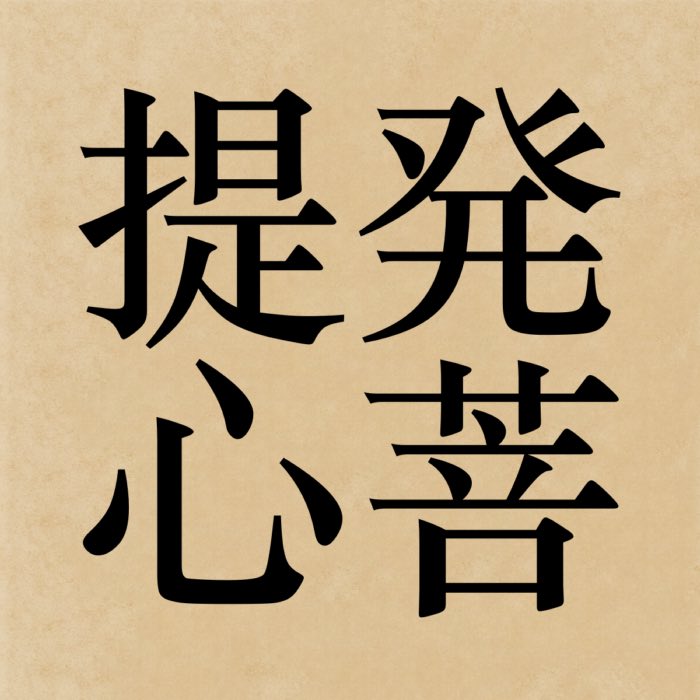

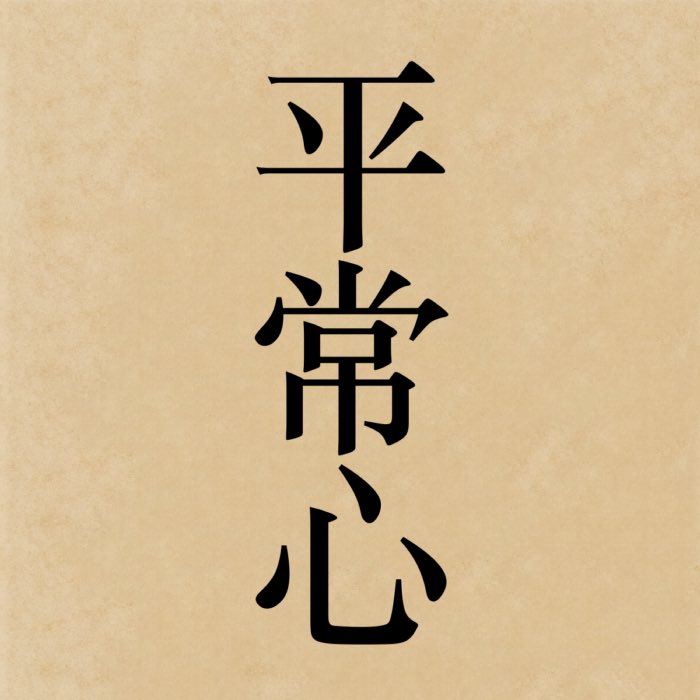

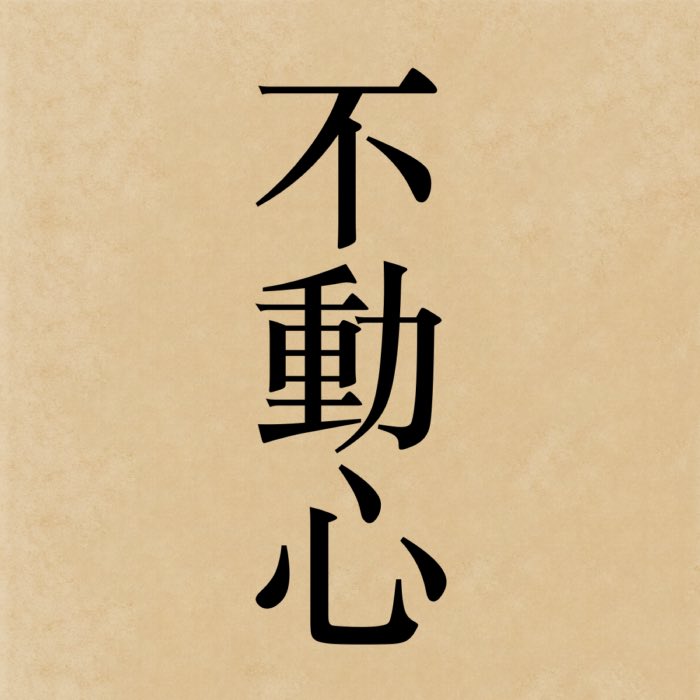

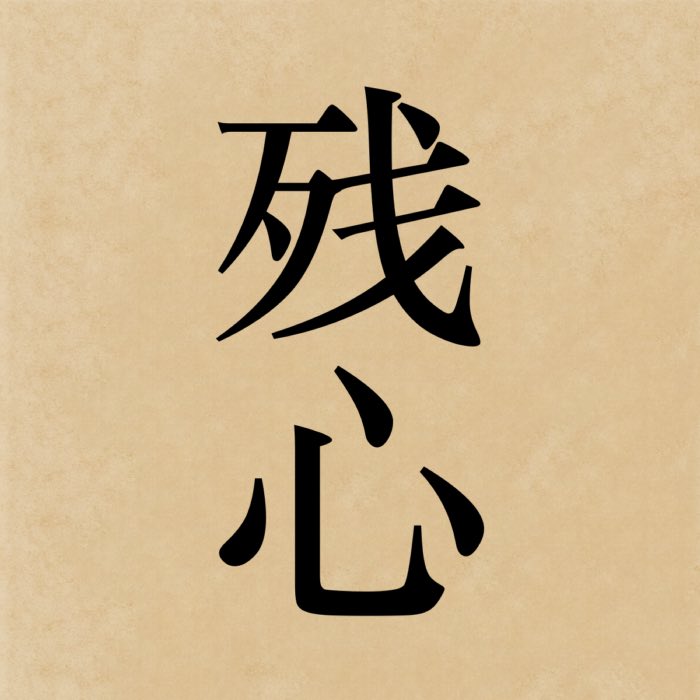

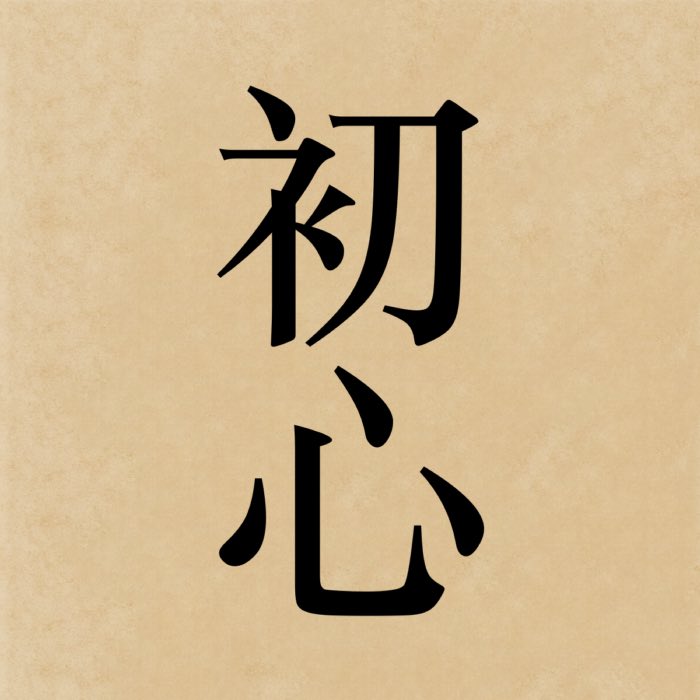

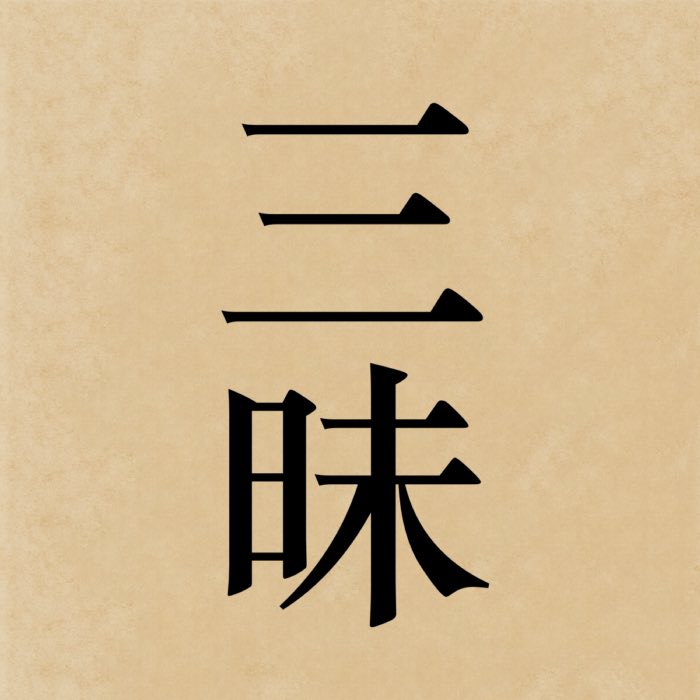

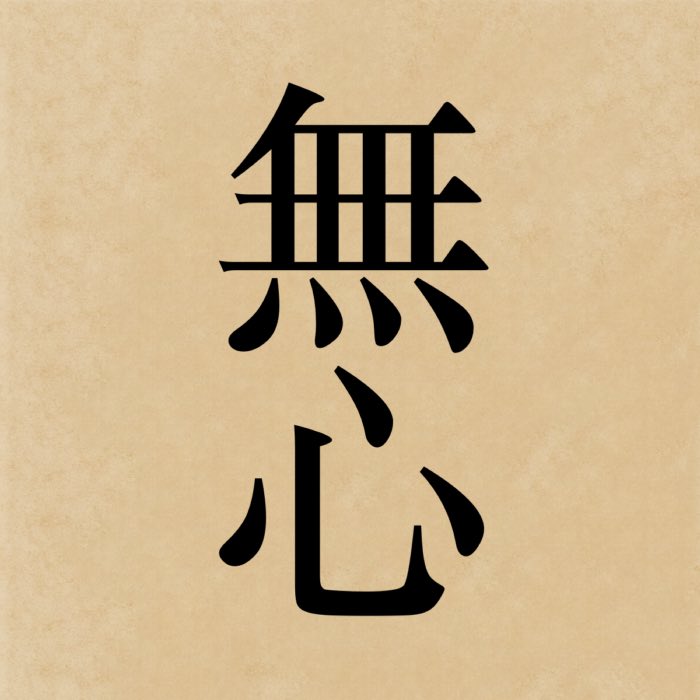

Kanji

Kanji are logographic characters borrowed from Chinese, each representing a meaning or concept. Unlike Chinese, Japanese uses kanji in conjunction with phonetic scripts to represent both meaning and grammatical function. Kanji can have multiple readings (on’yomi, the Chinese reading, and kun’yomi, the Japanese reading), depending on whether they are used in Chinese-derived compounds or native Japanese words.

Kanji are employed primarily for nouns, verbs, adjectives, and other core vocabulary, lending precision and depth to written Japanese. For instance, the kanji 本 (hon) means “book” or “origin”, depending on context.

The following table highlights some common kanji, their Japanese pronunciation (both on’yomi and kun’yomi) and Chinese (Pinyin), and their meanings:

| Kanji | Pronunciation (On’yomi / Kun’yomi) | Pinyin | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 日 | nichi / hi | rì | day, sun |

| 本 | hon / moto | běn | book, origin |

| 人 | jin / hito | rén | person |

| 月 | getsu / tsuki | yuè | month, moon |

| 水 | sui / mizu | shuǐ | water |

| 火 | ka / hi | huǐ | fire |

| 山 | san / yama | shān | mountain |

| 木 | moku / ki | mù | tree, wood |

These examples illustrate the versatility and depth of kanji, showcasing how a single character can convey multiple meanings and pronunciations depending on its usage.

Hiragana

Hiragana is a phonetic script developed in the 9th century from simplified kanji during the Heian period (794–1185 CE). It is used for grammatical elements, such as particles, verb endings, and native Japanese words without associated kanji. Hiragana’s flowing, cursive style made it popular in early Japanese literature.

The origin of hiragana is closely tied to the adaptation of Chinese characters to represent Japanese phonetics. The smallest phonological units, so-called morae or kana (仮名) in Japanese, are similar to syllables but can be shorter. The term kana is derived from the Chinese characters for “interim” (仮) and “name” (名), reflecting their role as phonetic symbols borrowed from Chinese characters.

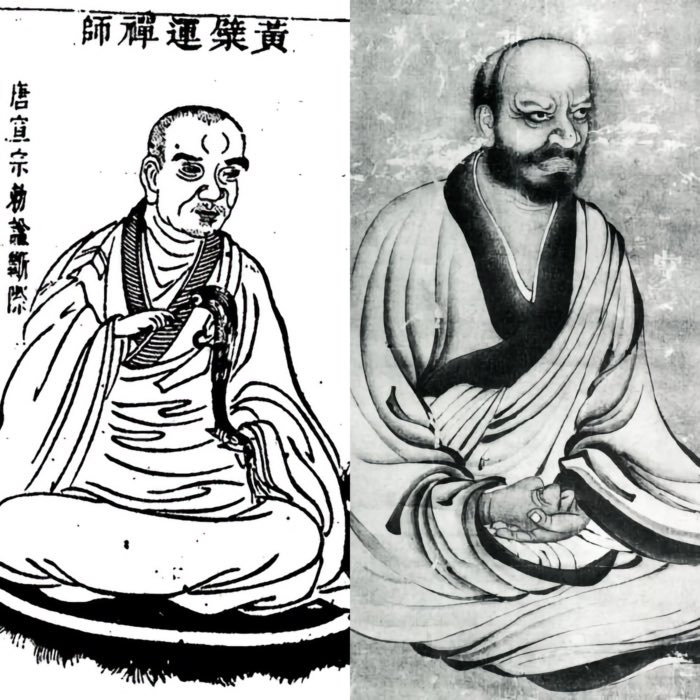

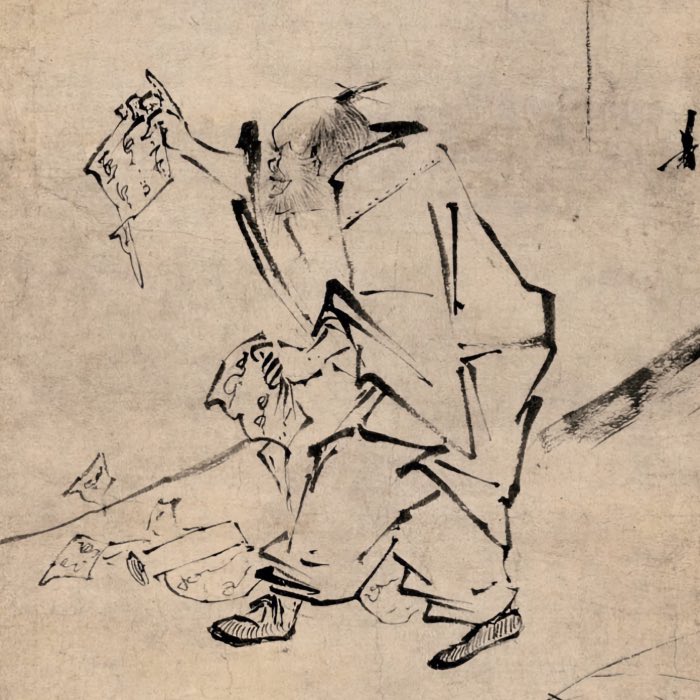

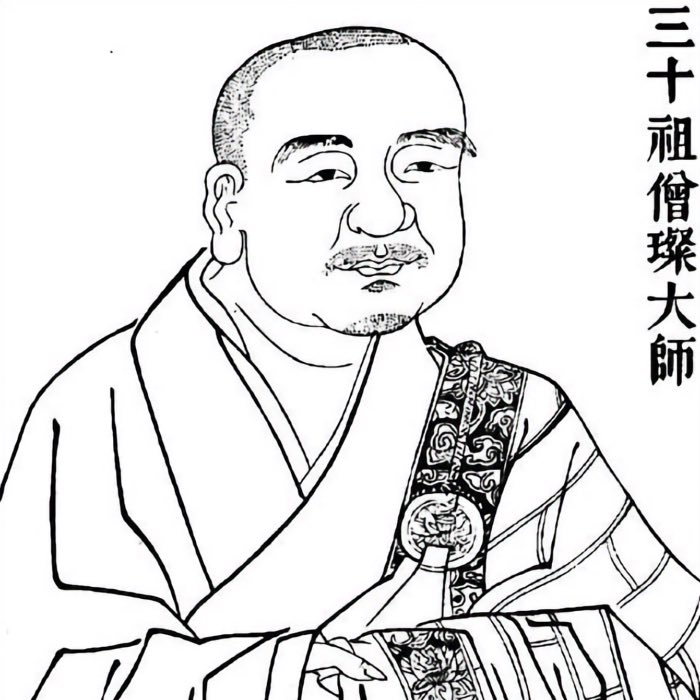

While he didn’t invent them, the Buddhist monk Kūkai (空海; 774-835) is credited with the standardization of the kana. In 804, Kūkai studied Sanskrit under two Indian masters to read sutras in their original language, which are still studied in Japan, mainly via Chinese translations. He also learned the syllabary Siddham, in which the sutras were written. After returning to Japan, he translated Sanskrit texts into Japanese, noting that Japanese syllables allowed for more accurate pronunciation than the limited Chinese transcription. In his Shingon-shū (真言宗) school of Buddhism, he began to phonetic symbols to transcribe Sanskrit sounds. After his death, this practice was continued by his followers and as a result, phonetic symbols were increasingly used in writing. Writing in phonetic script became common around 900, encouraged by Japanese poets who wrote their works using kana. This in turn ensured that Japanese literature began to break away from Chinese literature.

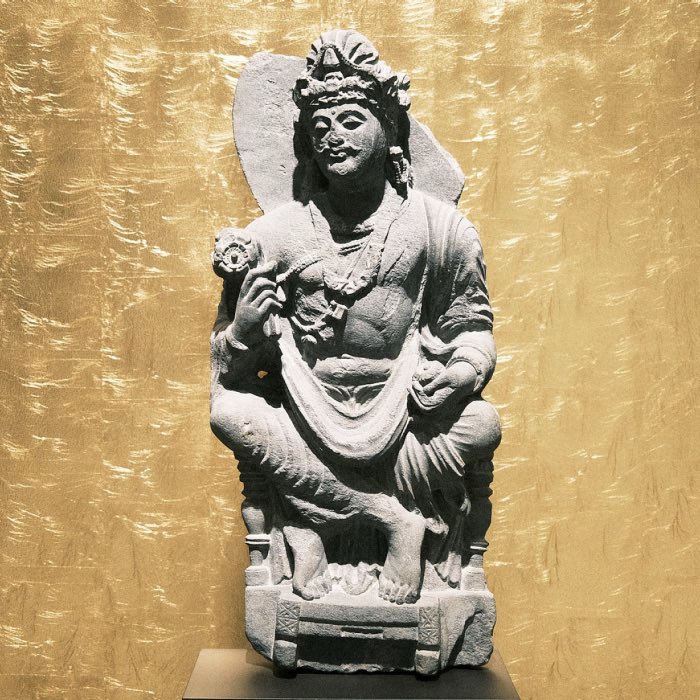

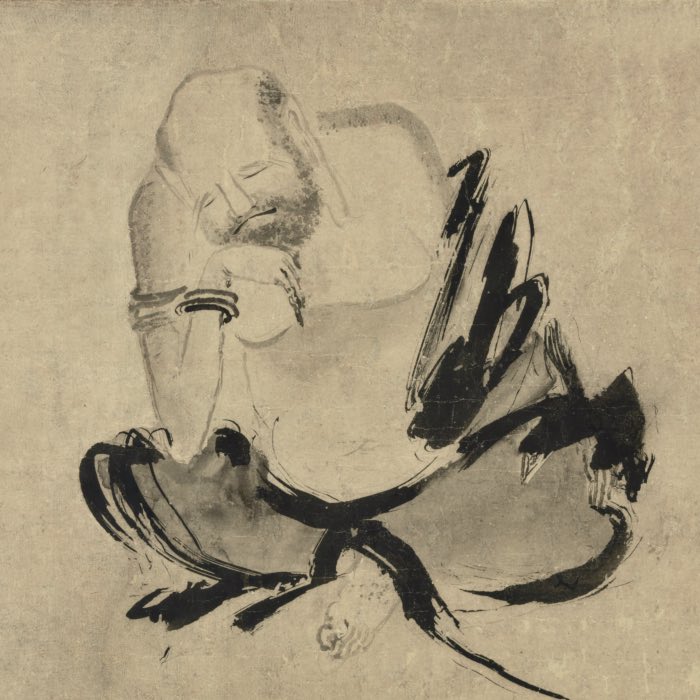

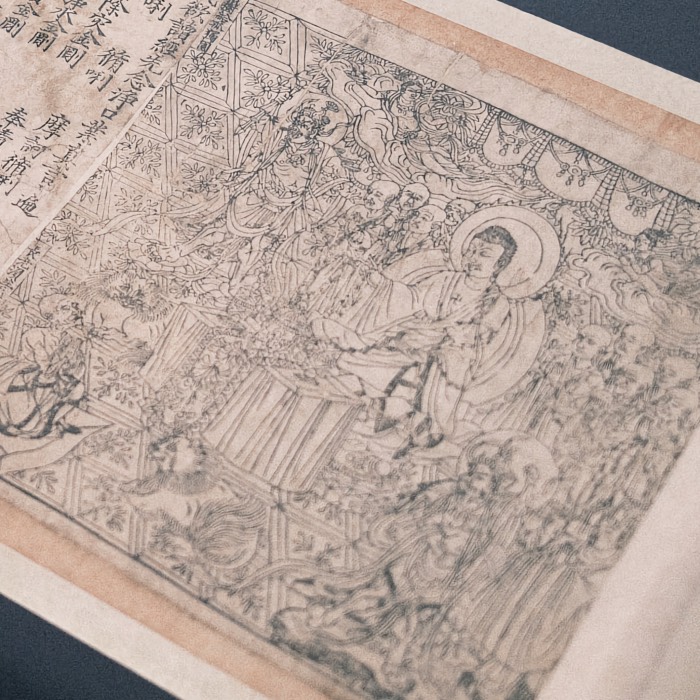

Painting of Kūkai (空海; his posthumous name is Kōbō Daishi, 弘法大師, which means “The Grand Master who Propagated the Dharma”) from the Shingon Hassozō, a set of scrolls depicting the first eight patriarchs of the Shingon-shū (真言宗), Japan, Kamakura period (13th-14th centuries). Kūkai, who played a crucial role in the development of the Japanese writing system, is generally a prominent figure in Japanese Buddhism. He is the founder of the esoteric Shingon school of Buddhism, which is one of the major schools of Japanese Buddhism. He is also prominent as a calligrapher, poet, and scholar. It is also said, that he never died but rather meditating in the mausoleum on Mount Kōya (高野山, Kōya-san), a large temple settlement in Wakayama Prefecture. At his mausoleum in Oku-no-in, food offerings are presented daily to him in the early morning and before noon. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

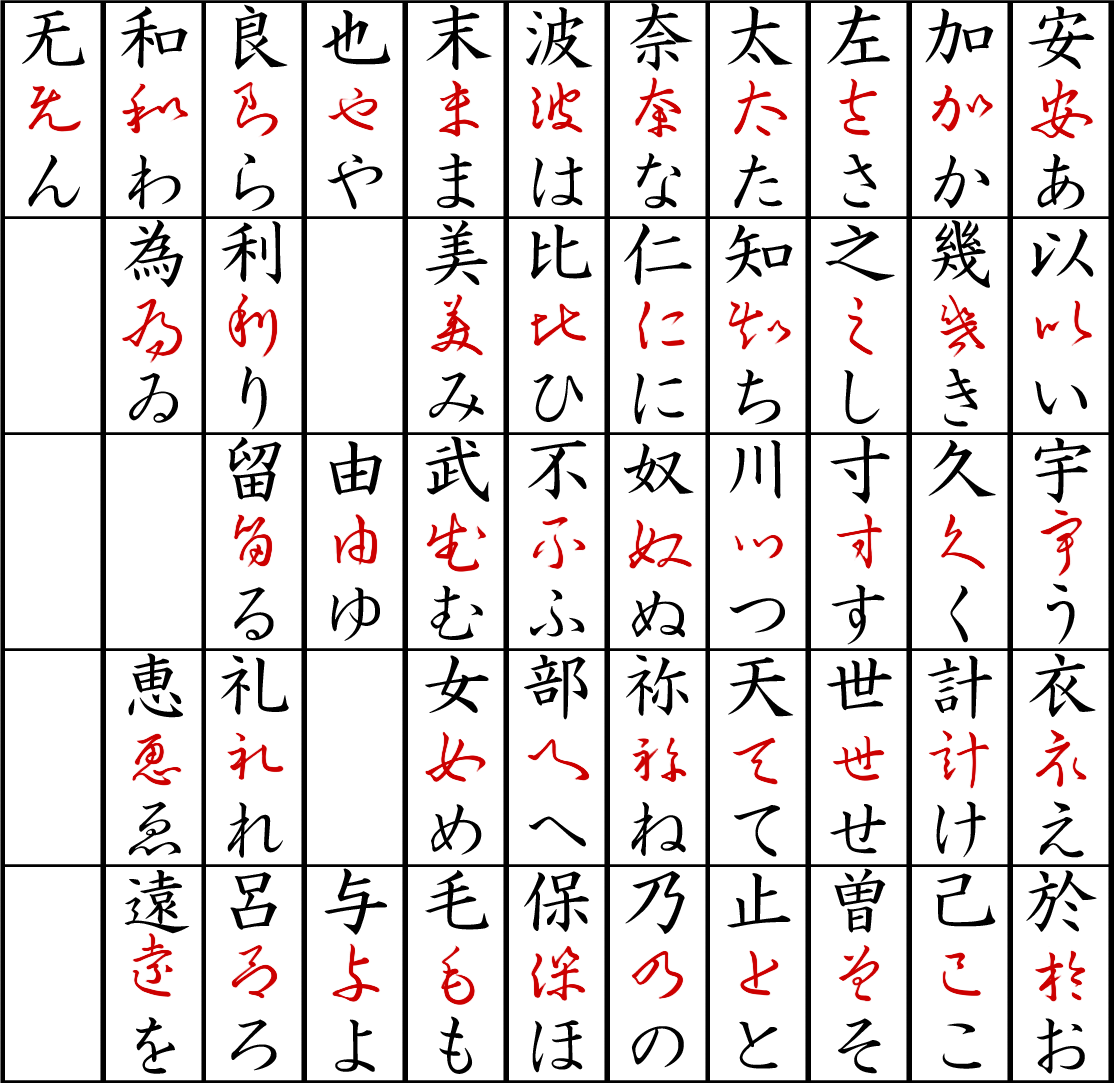

The earliest form of a kana-based writing system was man’yōgana (真仮名, ‘true kana’). It was already used in the early-7th century Kojiki (古事記, “Records of Ancient Matters”, 712) and Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, “Chronicles of Japan”, 720). The later development hentaigana is the historical variant of the now-standard hiragana. The forms of the hiragana originate from the cursive script style (sōsho) of Chinese calligraphy. The table below illustrates the the derivation from the regular Chinese script (upper letter) and cursive Chinese script (middle letters in red) to hiragana (lower letters):

Derivation of hiragana from Chinese characters (kanji). The upper letters show the regular Chinese script, the middle letters in red show the cursive Chinese script, and the lower letters show the hiragana. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Unlike kanji, which often carries semantic weight, each hiragana represents a single syllable, making it an essential tool for phonetic writing and grammatical precision. The following table provides examples of common hiragana, their pronunciation, and their meanings:

| Hiragana | Pronunciation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| あ | a | ah (sound) |

| い | i | ee (sound) |

| う | u | oo (sound) |

| え | e | eh (sound) |

| お | o | oh (sound) |

| か | ka | syllable “ka” |

| さ | sa | syllable “sa” |

| と | to | syllable “to” |

These examples highlight the phonetic nature of hiragana, where each character corresponds to a single sound, making it a foundational component of Japanese writing. However, some hiragana characters also carry grammatical functions. For example, the hiragana の (no) indicates possession or relation, as in watashi no hon (わたしの本, “my book”), as well as the hiragana は (ha), which is used as a topic marker, as in watashi wa gakusei desu (わたしは学生です, “I am a student”), where は highlights ‘I’ (わたし, watashi) as the topic of the sentence.

The hiragana script consists of 48 base characters, of which two (ゐ and ゑ) are only used in some proper names:

- 5 singular vowels: あ (a), い (i), う (u), え (e), お (o)

- 42 consonant–vowel unions: for example き (ki), て (te), ほ (ho), ゆ (ju), わ (wa)

- 1 singular consonant ん, romanized as n.

These characters are organized into a 5×10 grid, known as the gojūon (五十音, “fifty sounds”), as shown in the table below. The grid is read in such a way, that you combine the consonant with the vowel, e.g., the second row is read ka (か), ki (き), ku (く), ke (け), ko (こ) and so on. The first row is reserved for the vowels, a (あ), i (い), u (う), e (え), o (お):

| a | i | u | e | o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | あ | い | う | え | お |

| k | か | き | く | け | こ |

| s | さ | し | す | せ | そ |

| t | た | ち | つ | て | と |

| n | な | に | ぬ | ね | の |

| h | は | ひ | ふ | へ | ほ |

| m | ま | み | む | め | も |

| y | や | ゆ | よ | ||

| r | ら | り | る | れ | ろ |

| w | わ | ゐ | ゑ | を | |

| ん (n) |

There are some exceptions to the pronunciations: si→shi, ti→chi, tu→tsu, hu→fu, wi→i, we→e, wo→o.

The basic characters shown above can be further modified by, e.g. adding a double dot or dakuten marker ( ゛), which turns a voiceless consonant into a voiced consonant: k→g, ts/s→z, t→d, h/f→b and ch/sh→j (also u→v(u)). For example, ka (か) becomes ga (が). Hiragana beginning with an h (or f) sound can also add a handakuten marker ( ゜) changing the h (f) to a p. For example, ha (は) becomes pa (ぱ).

A so-called sokuon, っ, which looks like a small つ (tsu), signals that the following consonant is doubled. This distinction is crucial in Japanese pronunciation. For example:

- さか: saka, “hill”

- さっか: sakka, “author.

However, the sokuon cannot be used to double the consonant n. Instead, the singular ん (n) is placed before the syllable, as in みんな (minna, “all”). Additionally, the sokuon may occasionally appear at the end of an utterance, representing a glottal stop, as in “いてっ!” (ite, “Ouch!”).

Katakana

Katakana (片仮名 or カタカナ, “fragmentary kana”) is another phonetic script derived from kanji, i.e., from the introduction of kana. Like hiragana, it was developed in the 9th century by Buddhist monks in Nara to annotate Chinese texts and to translate Buddhist scriptures from India. Katakana is characterized by its angular, straight lines, in contrast to the curvilinear nature of hiragana. It is primarily used for foreign loanwords, onomatopoeia, and emphasis. For instance, the word “computer” is written as コンピューター (konpyūtā) in katakana. Katakana also serves specialized purposes, such as scientific terminology and the names of plants and animals.

Katakana was significantly influenced by Sanskrit, as its original creators interacted and collaborated with Indian Buddhists in East Asia during that period. Katakana was developed by simplifying parts of man’yōgana characters into a form of shorthand. For instance, ka (カ) is derived from the left side of the character ka (加, originally meaning “increase”, though this meaning is no longer relevant to kana). The table below illustrates the origins of each katakana symbol, with the red markings on the original Chinese characters (used as man’yōgana) showing how they evolved into their corresponding forms:

Table of katakana characters, and the kanji from which they derive. The roots of katakana are highlighted in red. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The following table provides examples of common katakana characters, their pronunciation, and their typical usage:

| Katakana | Pronunciation | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| ア | a | ah (sound) |

| イ | i | ee (sound) |

| ウ | u | oo (sound) |

| エ | e | eh (sound) |

| オ | o | oh (sound) |

| カ | ka | syllable “ka” |

| サ | sa | syllable “sa” |

| ト | to | syllable “to” |

| ス | su | syllable “su” |

| ノ | no | possession, relation |

These examples illustrate the phonetic role of katakana, particularly in adapting foreign words and representing sounds that are not typically written in kanji or hiragana.

The katakana script consists of 48 characters, not counting functional and diacritic marks:

- 5 vowel nucleus characters

- 42 core syllabograms (onset-nucleus combinations), formed by pairing nine consonants with the five vowels, with three non-canonical combinations (yi, ye, and wu)

- 1 coda consonant

Like hiragana, these characters are organized into gojūon (5x10 grid). The grid is read in such a way, that you combine the consonant with the vowel, e.g., the second row is read ka (カ), ki (キ), ku (ク), ke (ケ), ko (コ) and so on. The first row is reserved for the vowels, a (ア), i (イ), u (ウ), e (エ), o (オ):

| a | i | u | e | o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | ア | イ | ウ | エ | オ |

| k | カ | キ | ク | ケ | コ |

| s | サ | シ | ス | セ | ソ |

| t | タ | チ | ツ | テ | ト |

| n | ナ | ニ | ヌ | ネ | ノ |

| h | ハ | ヒ | フ | ヘ | ホ |

| m | マ | ミ | ム | メ | モ |

| y | ヤ | ユ | ヨ | ||

| r | ラ | リ | ル | レ | ロ |

| w | ワ | ヰ | ヱ | ヲ | |

| ン (n) |

A dakuten ( ゛) indicates a primary alteration; most often it voices the consonant: k→g, s→z, t→d and h→b; for example, ka (カ) becomes ga (ガ). Secondary alteration, where possible, is shown by a circular handakuten: h→p; for example; ha (ハ) becomes pa (パ ).

Romanization (Rōmaji)

In addition to the three main scripts, Japanese can be transcribed using the Roman alphabet (rōmaji), which is often employed for language learners, brand names, and digital input methods. However, rōmaji is not used in traditional Japanese writing.

The following table illustrates some examples of rōmaji, their corresponding Japanese words, and meanings:

| Rōmaji | Japanese word | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| taberu | たべる | to eat |

| hanasu | はなす | to speak |

| ai | あい | love |

| san | さん | Mr./Ms. |

| sakura | さくら | cherry blossom |

| konnichiwa | こんにちは | hello |

| sushi | すし | sushi |

| mizu | みず | water |

Writing directions

Japanese is traditionally written vertically from right to left, with columns arranged from top to bottom. This format is known as tategaki (縦書き, “vertical writing”) and roots in the Chinese origin of the writing system. However, horizontal writing from left to right, known as yokogaki (横書き, “horizontal writing”), has become more common in modern contexts, such as newspapers and novels. The choice of writing direction depends on the medium and the writer’s preference.

A book printed in tategaki opens with the spine of the book to the right, while a book printed in yokogaki opens with the spine to the left.

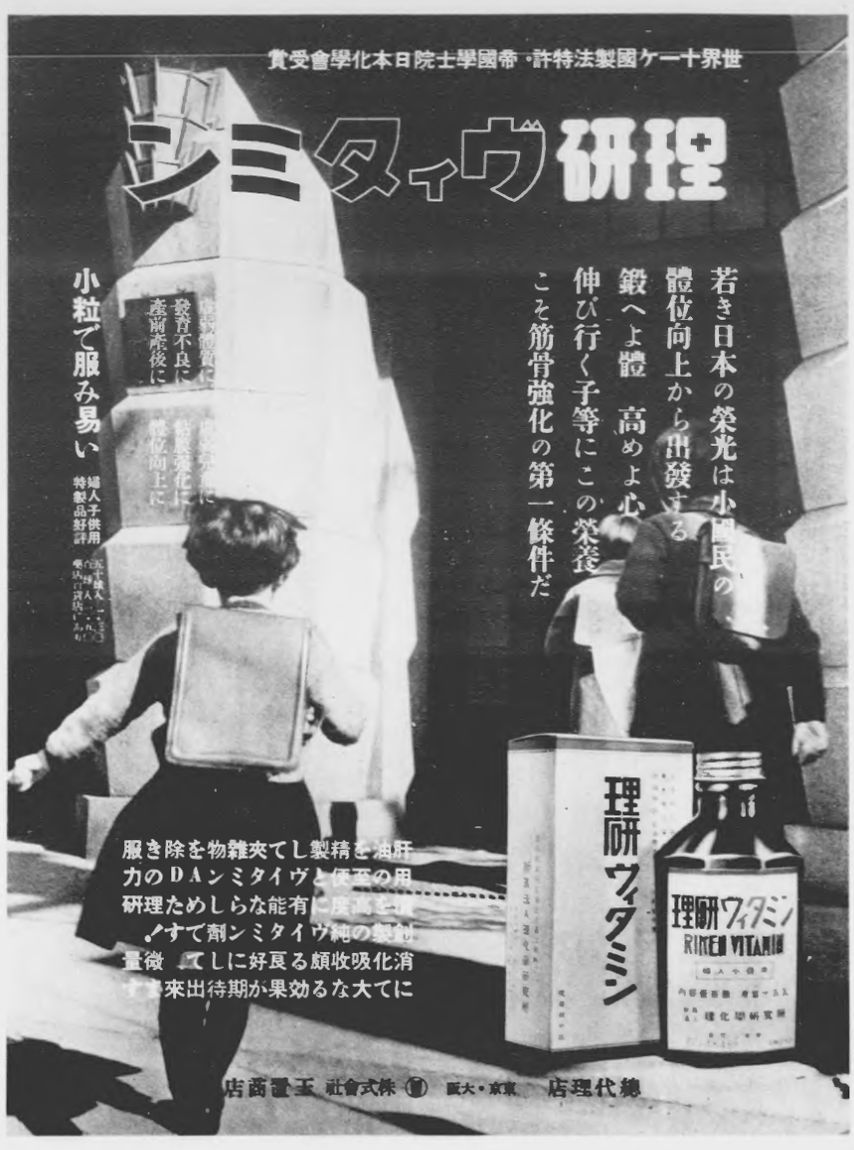

Integration and complexity

The coexistence of kanji, hiragana, and katakana (and rōmaji) makes the Japanese writing system one of the most complex in the world. Each script serves a distinct purpose, creating a dynamic interplay between meaning, sound, and grammar. Often, all three scripts as well as the two writing directions are used at the same time, for example in newspapers.

Advertising poster from 1938 with three font directions. At the top, the name of the product on the right: ンミタィヴ研理 (n mi ta vi ken ri), on the bottle shown the same name on the left: 理研ヴィタミン (ri ken vi ta mi n), on the box next to it from top to bottom. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: Public domain).

Conclusion

The Japanese language and its writing systems embody a remarkable blend of historical influences, cultural innovation, and linguistic evolution. From its uncertain origins to its development as a sophisticated modern language, Japanese offers unique insights into the interplay between language, society, and identity. Its writing system, with the harmonious integration of kanji, hiragana, and katakana, stands as a testament to Japan’s ability to adapt and innovate while preserving its rich cultural heritage.

References and further reading

- Frellesvig, Bjarke, A history of the Japanese language, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0-521-65320-6

- Kindaichi, Haruhiko, Hirano, Umeyo, The Japanese Language, 1978, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 978-0-8048-1579-6

- Kuno, Susumu, The structure of the Japanese language, 1973, MIT Press, ISBN: 0-262-11049-0

- Coulmas, F., Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis, 2003, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521787376

- Beckwith, Christopher I., Koguryo, the Language of Japan’s Continental Relatives, 2004, Brill, ISBN: 978-90-04-13949-7

- Shibatani, Masayoshi, The languages of Japan; 1990, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 0-521-36070-6

- Tsujimura, Natsuko, An introduction to Japanese linguistics, 1996, Blackwell Publishers, ISBN: 0-631-19855-5

- Habu, Junko, Ancient Jomon of Japan, 2004, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Press, ISBN: 978-0-521-77670-7

- Imamura, Keiji, Prehistoric Japan, 1996, University of Hawai`i Press,ISBN: 0-8248-1852-0

- Robbeets, Martine Irma, Is Japanese Related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic?, 2005, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN: 978-3-447-05247-4

- Labrune, Laurence, The Phonology of Japanese, 2012, Oxford University Press, doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199545834.003.0003ꜛ

- Martin, Samuel E., The Japanese Language Through Time, 1987, Yale University, ISBN: 0-300-03729-5

- Nanette Gottlieb, Kanji Politics. Language Policy and Japanese Script, 1996 Kegan Paul International, ISBN: 0-7103-0512-5.

- Yaeko Sato Habein, The History of the Japanese Written Language, 1984, University of Tokyo Press, ISBN: 0-86008-347-0.

- Wolfgang Hadamitzky, Kanji & Kana – Die Welt der japanischen Schrift in einem Band, 2012, Iudicium, München, ISBN: 978-3-86205-087-1

- Christopher Seeley, A History of Writing in Japan, 1991, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN: 90-04-09081-9

- Miyake, Marc Hideo, Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction, 2003, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN: 0-415-30575-6

- Yujiro Nakata, The Art of Japanese Calligraphy, 1976, Weatherhill/Heibonsha, 2nd print, ISBN: 0-8348-1013-1

- McAuley, Thomas E., Language change in East Asia, 2001, Routledge, ISBN: 0700713778

- Roy Andrew Miller, The Japanese language, ISBN 0-226-52718-2; or Language and Literature - Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages: Studies in Honour of Roy Andrew Miller on His 75th Birthday by Karl H Menges and Nelly Naumann, 1999, Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN: 978-3447041799

- Comrie, Bernard, The World’s Major Languages, 2018, Taylor & Francis Ltd., ISBN: 978-1138184824

- Wikipedia article on Japonic languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Classification of the Japonic languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Ryukyuan languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Altaic languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Austronesian languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Austro-Tai languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Kra–Dai languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Koreanic languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Japanese diasporaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Old Japaneseꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Early Middle Japaneseꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Late Middle Japaneseꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Honorific speech in Japaneseꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Japanese dialectsꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Japanese writing systemꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Hiraganaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Katakanaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Kanaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Kūkaiꜛ

comments