Origins of the Chinese language and writing system

The Chinese language and its writing system represent one of the most enduring and unique linguistic traditions in human history. Rooted in the Sino-Tibetan language family, Chinese evolved in a completely different cultural and historical context compared to the Indo-European languages, such as Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. In this post, we briefly explore its origins and development, its linguistic characteristics and significance in world history.

Map of today’s Chinese-speaking world. Dark green: Majority Chinese-speaking, Semi-dark green: Significant Chinese-speaking population, Light green: Status as an official or educational language. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Origins of the Chinese language

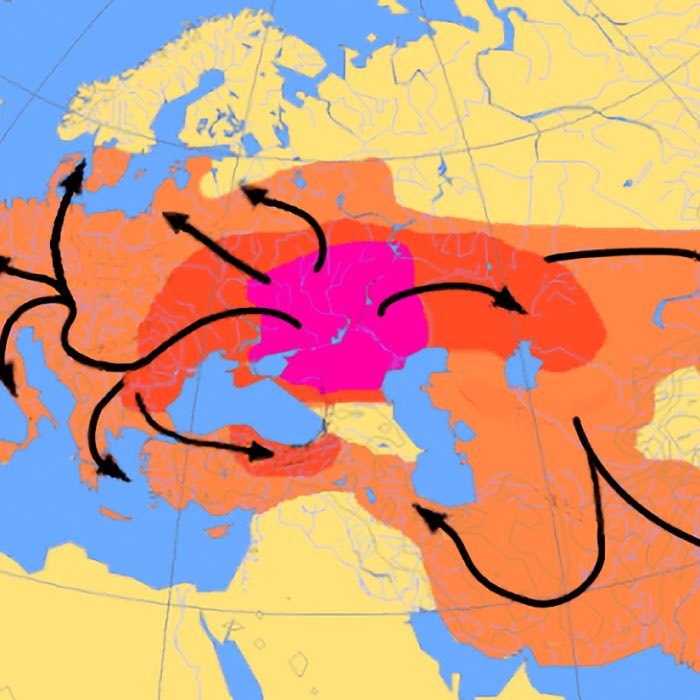

The Chinese language is a member of the Sino-Tibetan language family, which includes languages spoken in China, Tibet, Myanmar, and other parts of East Asia. Scholars estimate that Proto-Sino-Tibetan, the common ancestor of this family, was spoken approximately 4,000 to 6,000 years ago. Unlike the Indo-European family, whose reconstruction has been aided by extensive historical records and linguistic diversity, the reconstruction of Proto-Sino-Tibetan remains challenging due to limited historical documentation and significant divergence among its descendant languages.

Groupings of Sino-Tibetan languages. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Old Chinese

The earliest stage of the Chinese language is known as Old Chinese (Shànggǔ Hànyǔ), spoken during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). Old Chinese forms the linguistic foundation of Classical Chinese, the literary standard for millennia. This language is reconstructed primarily through ancient texts such as the Shījīng (Book of Songs) and bronze inscriptions, as well as phonetic evidence preserved in later Chinese dictionaries.

Western Zhou royal domain (dashed outline), capitals and colonies (black squares) and archaeological sites. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Old Chinese had a relatively simple syllable structure compared to modern Chinese and lacked the tonal distinctions that characterize Mandarin today. It featured a rich inventory of consonants, including clusters that were subsequently simplified over time. Morphologically, Old Chinese relied heavily on word compounding and affixation to form new meanings, a trait that continues to influence the language today.

Middle and modern Chinese

Middle Chinese, spoken from the Sui to Tang dynasties (6th to 10th centuries CE), represents the transitional stage between Old and Modern Chinese. This period saw the emergence of tones as a linguistic feature, likely evolving from earlier phonemic distinctions. The phonological changes during this period laid the groundwork for the diverse Chinese dialects spoken today.

Modern Chinese, particularly Mandarin, emerged as the standard language during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Mandarin’s simplified grammar and pronunciation compared to other dialects facilitated its adoption as the lingua franca of China. However, regional dialects like Cantonese, Wu, and Min continue to preserve features of earlier Chinese.

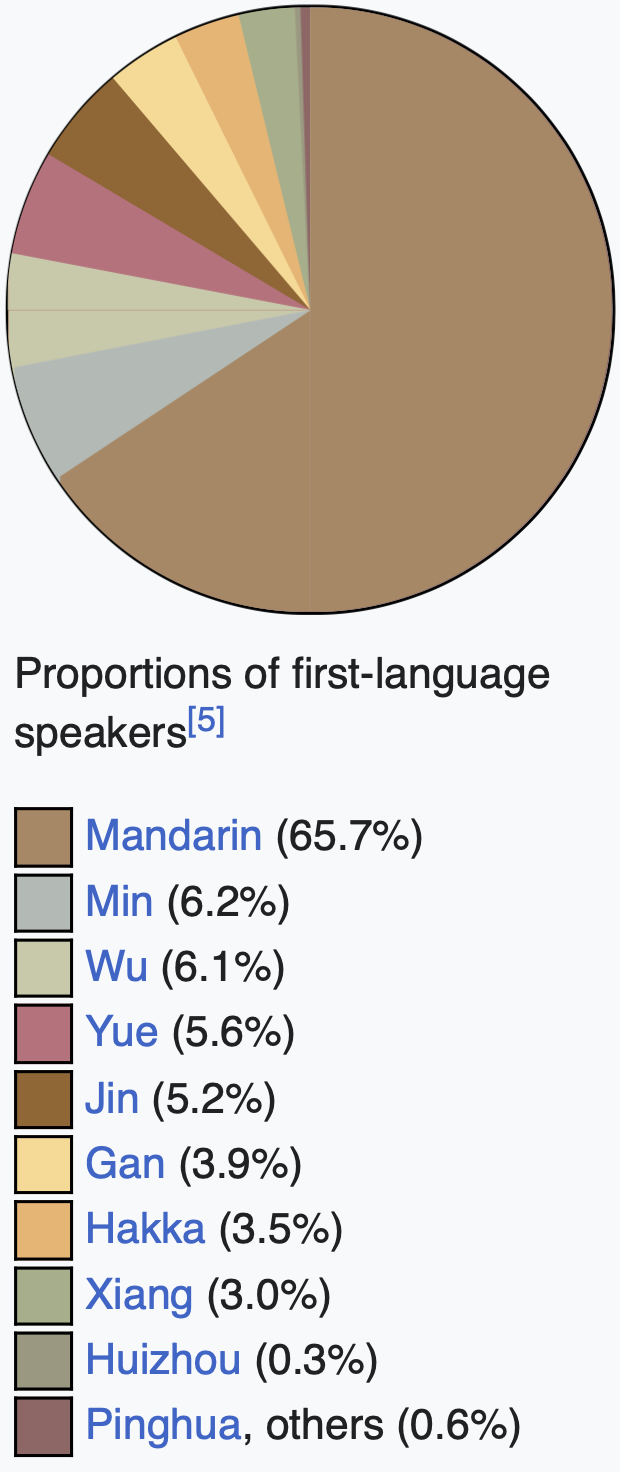

Left: Range of dialect groups in China proper and Taiwan according to the Language Atlas of China Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Proportions of first-language speakers of Chinese dialects. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Phonology

Syllables in the Chinese languages have unique characteristics that link phonology closely to both morphology and the structure of the writing system. Each syllable adheres to fixed phonological rules, which define its composition and tonal properties.

Chinese syllables typically consist of three components:

- Onset: A consonant or consonant-glide combination; in some cases, there may be no onset.

- Nucleus: Usually a vowel, which may be a monophthong, diphthong, or triphthong, though exceptions exist. For instance, in Cantonese, nasal sonorant consonants like /m/ and /ŋ/ can function as a syllable’s nucleus.

- Coda: An optional ending consonant. In Mandarin, the possible codas are limited to nasals (/n/, /ŋ/), the retroflex approximant (/ɻ/), or the absence of a coda altogether.

Mandarin syllables are predominantly open, meaning they lack a coda, though some varieties of Chinese permit a broader range of coda consonants, including voiceless stops such as /p/, /t/, and /k/. Over time, Mandarin and other dialects have seen a reduction in the range of phonetic elements compared to historical Middle Chinese, resulting in fewer syllables overall and an increased reliance on polysyllabic words.

Tones are an essential feature of all spoken Chinese varieties, used to distinguish words that share the same phonetic composition. Tone systems vary widely across dialects:

- Northern dialects: Typically have fewer tones (e.g., three tones in some varieties).

- Southern dialects: Can have up to six or more tones, depending on how they are classified.

- Shanghainese: This variety has simplified its tonal system to a two-tone pitch accent system, resembling Japanese.

In Standard Mandarin, there are four primary tones and a neutral tone. These tones are critical for distinguishing otherwise identical syllables. For instance, the syllable “ma” can mean “mother”, “hemp”, “horse”, or “scold”, depending on its tone:

| Tone | Character | Gloss | Pinyin | Pitch contour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 妈 (媽) | mother | mā | ˥ |

| 2 | 麻 | hemp | má | ˧˥ |

| 3 | 马 (馬) | horse | mǎ | ˨˩˦ |

| 4 | 骂 (罵) | scold | mà | ˥˩ |

| Neutral | 吗 (嗎) | question particle | ma | varies |

The pitch contour represents the variation in pitch over the duration of a tone, which defines the tonal quality of a syllable in tonal languages like Chinese.

Phonological trends

Modern Chinese varieties, especially Mandarin, have experienced a simplification of their phonological systems compared to historical stages like Middle Chinese. This has resulted in:

- Fewer syllables: The total number of distinct syllables in Mandarin, including tonal variations, is around 1,000 — significantly fewer than in languages like English.

- Polysyllabic words: Due to the reduction in syllables, Mandarin relies more heavily on polysyllabic compounds to convey meaning.

Origins of Chinese writing

The Chinese writing system, or Hanzi (汉字 in Simplified Chinese, 漢字 in Traditional Chinese), is one of the oldest and most enduring in the world, with a history spanning over 3,000 years. Rooted in logographic characters, Chinese writing is distinct from the alphabetic scripts of Indo-European languages. The development of Chinese writing reflects the cultural, political, and technological advancements of ancient China, shaping the language’s evolution and its role in Chinese civilization.

Oracle Bone Script

The earliest known Chinese writing, Oracle Bone Script (Jiǎngǔwén), dates back to the Shang Dynasty (circa 1200 BCE). These inscriptions, carved on turtle shells and animal bones, were used for divination and reflect an already advanced stage of script development. Oracle Bone Script reveals the foundational principles of what later became known as Hanzi, the Chinese characters: morphemes or words represented rather than phonetic units.

Left: Locations of the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC) marked in violet, with Shang capitals in marked by red dots. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Right: ‘Shang’ in oracle bone script (top left), bronze script (top right), seal script (bottom left), and regular script (bottom right) forms. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Script on bone, oracle bone script on bone and tortoise shell, Anyang, Henan Province (replica, gifts of the China Printing Museum, Beijing). Before making important decisions, Chinese rulers consulted their ancestors: cattle shoulder blade bones and tortoise shells were placed in the fire. The cracks caused by the heat were read as an omen of things to come. After the ritual, the day and reason for the questioning as well as the answer were carved on the bones. The signs used for this are called called ‘oracle bone writing’ today. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Script on bone, oracle bone script on bone and tortoise shell, Anyang, Henan Province (replica, gifts of the China Printing Museum, Beijing). Before making important decisions, Chinese rulers consulted their ancestors: cattle shoulder blade bones and tortoise shells were placed in the fire. The cracks caused by the heat were read as an omen of things to come. After the ritual, the day and reason for the questioning as well as the answer were carved on the bones. The signs used for this are called called ‘oracle bone writing’ today. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Graphical evolution of pictographs. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Evolution of Chinese script

Over time, Chinese writing underwent significant transformations, evolving through several distinct stages:

- Bronze inscriptions (Jīnwén): Found on ceremonial vessels from the Zhou Dynasty, these inscriptions were more stylized than Oracle Bone Script and show early standardization.

- Seal Script (Zhuànshū): Standardized during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), Seal Script represents a key milestone in the unification of Chinese writing. Its rounded and intricate forms were used for official inscriptions.

- Clerical Script (Lìshū): Emerging during the Han Dynasty, Clerical Script simplified the elaborate strokes of Seal Script, making writing faster and more practical for administrative use. This script further refined the structure of Hanzi, laying the groundwork for its modern forms.

- Cursive Script (Cǎoshū): Developed from Clerical Script, Cursive Script is a highly stylized and fluid form of writing used for personal correspondence and artistic expression.

- Semi-cursive Script (Xíngshū): A hybrid of Clerical and Cursive Scripts, Semi-cursive Script combines legibility with artistic flair, popular during the Tang Dynasty.

- Regular Script (Kǎshū): By the Eastern Jin Dynasty (4th–5th centuries CE), Regular Script became the standard style of writing Hanzi. It emphasizes legibility, balance, and aesthetic precision, becoming the form most commonly taught and used today.

Evolution of Chinese characters, exemplarily shown for the characters “heaven” (天), “horse” (馬), “travel” (旅), and “straight”, (正) and “leather” (韋). The characters are shown in different scripts and styles, from top to bottom: Oracle Bone Script, Bronze Script, Small Seal Script, Clerical Script, Cursive Script, Semi-Cursive Script, and Regular Script. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0).

The first four characters of the 6th-century Thousand Character Classic in different styles. From right to left: seal script, clerical script, regular script, Song type, and sans-serif type. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Hanzi characters are used to write not only Chinese but have also influenced the writing systems of other languages, such as Japanese (Kanji) and Korean (Hanja). Today, there are over 50,000 Hanzi characters, though only around 8,000 are commonly used, and only about 3,000 are frequently used in Chinese media and newspapers. However, Chinese characters should not be confused with Chinese words. Because most Chinese words are made up of two or more characters, there are many more Chinese words than characters. A more accurate equivalent for a Chinese character is the morpheme, as characters represent the smallest grammatical units with individual meanings in the Chinese language.

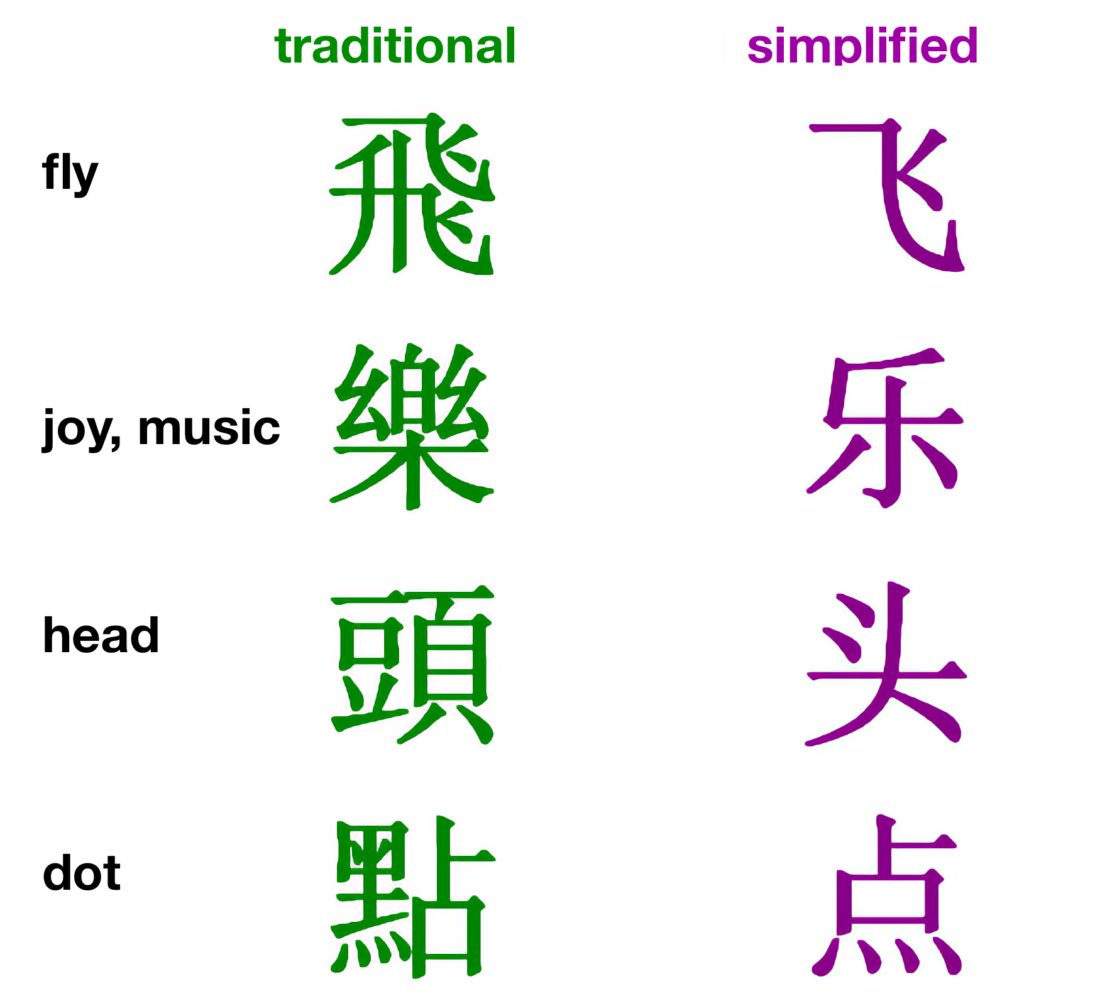

Traditional vs. Simplified Chinese characters. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (modified) (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

In modern China, Hanzi are divided into two main forms: Traditional Chinese characters, used in regions such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, and Simplified Chinese characters, adopted in Mainland China by the government in the 1950s to promote literacy by reducing the number of strokes in many characters.

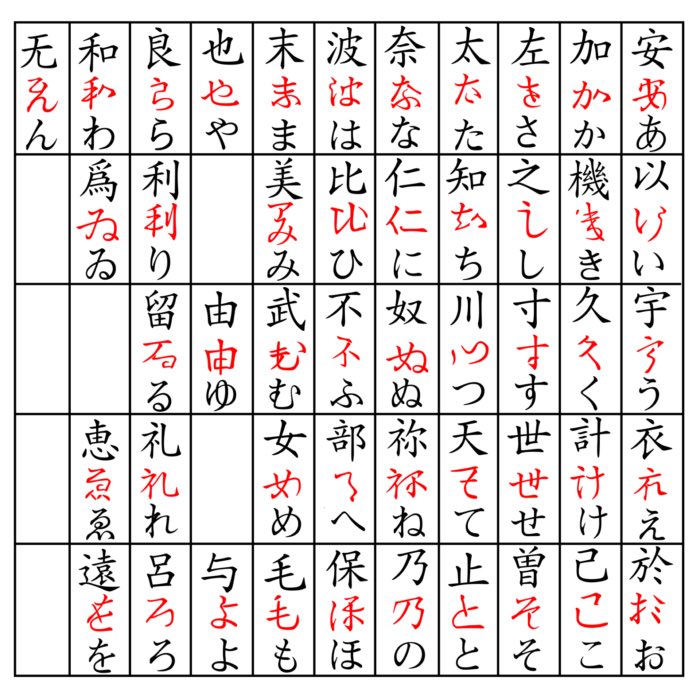

Other countries that historically used Chinese characters also simplified their writing systems. For example, Japan introduced two syllabic scripts, Hiragana and Katakana, in addition to Chinese characters, and Korea developed its own alphabetic script, Hangul, in the 15th century, which is used until today in both North and South Korea.

Radicals: The building blocks of Hanzi

Radicals (bùshǒu, 部首) are fundamental components of Hanzi that play a crucial role in their structure, meaning, and organization. Each Hanzi character is composed of one or more radicals, which serve as semantic or phonetic clues.

The Role of Radicals:

- Semantic clues: Many radicals provide hints about the meaning of a character. For example:

- The radical 水 (shuǐ), meaning “water”, appears in characters related to liquids, such as 海 (hǎi, “sea”).

- The radical 火 (huǒ), meaning “fire”, is found in characters like 炎 (yán, “flame”) and 热 (rè, “hot”).

- Phonetic clues: Some radicals contribute to the pronunciation of a character. For instance:

- The character 海 (hǎi, “sea”) includes the radical 水 (shuǐ, “water”) for meaning and 浩 (hǎo) as a phonetic component.

- Dictionary organization: Radicals are used to categorize and index characters in traditional Chinese dictionaries, making it easier to locate and study specific characters.

There are 214 traditional radicals, though modern systems often use fewer. Some common examples include:

- 人 (rén): “person”

- 口 (kǒu): “mouth”

- 木 (mù): “wood”

- 日 (rì): “sun”

The radical for the Chinese character 媽 (mā; ‘mother’) is the semantic component ⼥ ’woman’ on its left side. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (modified) (license: public domain).

Radicals can appear in various positions within a character, contributing to its overall structure. For instance, the radical 女 typically appears on the left in characters like 姐, 媽, 她, 好, and 姓, but it is positioned at the bottom in 妾. Generally, semantic components are found on the top or left side of a character, while phonetic components are located on the right side or at the bottom. However, these are flexible guidelines, and exceptions are numerous. In some cases, a radical spans multiple sides of a character, as in 園 (where 囗, meaning “enclosure”, surrounds 袁) or 街 (where 行, meaning “go” or “movement”, combines with 圭). Even more intricate combinations exist, such as 勝, which merges 力 (“strength”) with 朕, where the radical occupies the lower-right quadrant. Such configurations illustrate the complexity and versatility of radicals in shaping Chinese characters. In many Chinese characters, the components, including radicals, are often altered or adjusted in form to fit harmoniously within the character’s overall structure.

Radicals not only provide insights into the characters’ meanings and pronunciations but also highlight the interconnectedness of the Chinese writing system. Mastery of radicals is essential for understanding and learning Hanzi efficiently.

Romanization: Wade-Giles and Pinyin

The Romanization of Chinese has played a crucial role in bridging the linguistic gap between Chinese and non-Chinese speakers. Two major systems, Wade-Giles and Pinyin, have been developed for this purpose, each reflecting different historical and linguistic priorities.

Wade-Giles

Developed in the mid-19th century by Thomas Wade and later refined by Herbert Giles, the Wade-Giles system was one of the first systematic attempts to Romanize Mandarin Chinese. It relies on an older phonetic system and employs apostrophes to distinguish aspirated from unaspirated consonants. For example, p’ing in Wade-Giles corresponds to ping in Pinyin, and t’ai corresponds to tai.

Wade-Giles was widely used in Western academia and publications throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, its complexity, including the use of diacritical marks and inconsistent application, posed challenges for learners and users. Despite these limitations, Wade-Giles left a lasting legacy, particularly in older texts and anglicized names still in use today.

For example:

- The character 北京 (Běijīng in Pinyin) was Romanized as Peking in Wade-Giles.

- The name of the Daoist text 道德經 (Dàodéjīng in Pinyin) appeared as Tao Te Ching in Wade-Giles.

Pinyin

To aid in pronunciation and facilitate learning, the Chinese government developed Hanyu Pinyin in the 1950s. Pinyin represents the sounds of Mandarin Chinese using the Roman alphabet and provides a standardized approach to Romanization. While it is not a replacement for Chinese characters, Pinyin serves as a practical tool for teaching, inputting text on digital devices, and transcribing Chinese names and words in international contexts.

Pinyin simplifies the learning process and removes many of the ambiguities present in earlier systems like Wade-Giles. Its systematic approach to Mandarin phonetics has made it the official Romanization system in China and an international standard.

The following table illustrates examples of Traditional Chinese characters and their Romanization in both Pinyin and Wade-Giles, highlighting the differences between the two systems:

| Traditional Character | Pinyin | Wade-Giles | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 水 | shuǐ | shui | water |

| 中國 | Zhōngguó | Chung-kuo | China |

| 人類 | rénlèi | jen-lei | human |

| 家 | jiā | chia | house |

| 一 | yī | i | one |

| 龍 | lóng | lung | dragon |

| 書 | shū | shu | book |

| 月 | yuè | yüe | moon |

| 孔子 | Kǒngzǐ | K’ung Tsu | Confucius |

| 蔣介石 | Jiǎng Jièshí | Chiang Chieh-shih | Chiang Kai-shek |

| 毛澤東 | Máo Zédōng | Mao Tse-tung | Mao Zedong |

| 臺北 | Táiběi | T’ai-pei | Taipei |

| 臺灣 | Táiwān | T’ai-wan | Taiwan |

| 中國 | Zhōngguó | Chung-kuo | China |

Conclusion

The origins of the Chinese language and writing system reveal a rich linguistic and cultural heritage distinct from the Indo-European tradition. While Chinese evolved from the Sino-Tibetan family with a logographic writing system designed for semantic clarity, Indo-European languages like Sanskrit relied on phonetic scripts to preserve their linguistic complexity. These differences underscore the diverse paths of human communication and their adaptation to cultural, historical, and practical needs.

By examining these two traditions side by side, we gain a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity of human language and the role it plays in shaping civilizations.

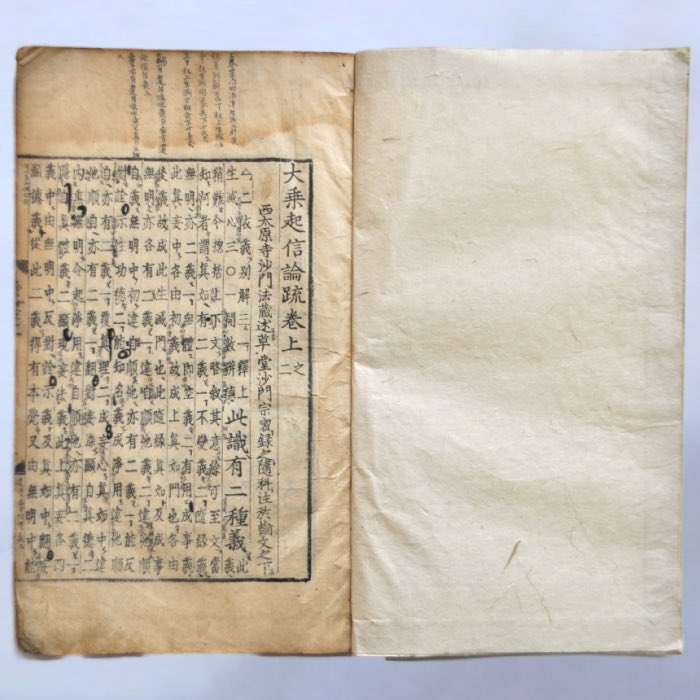

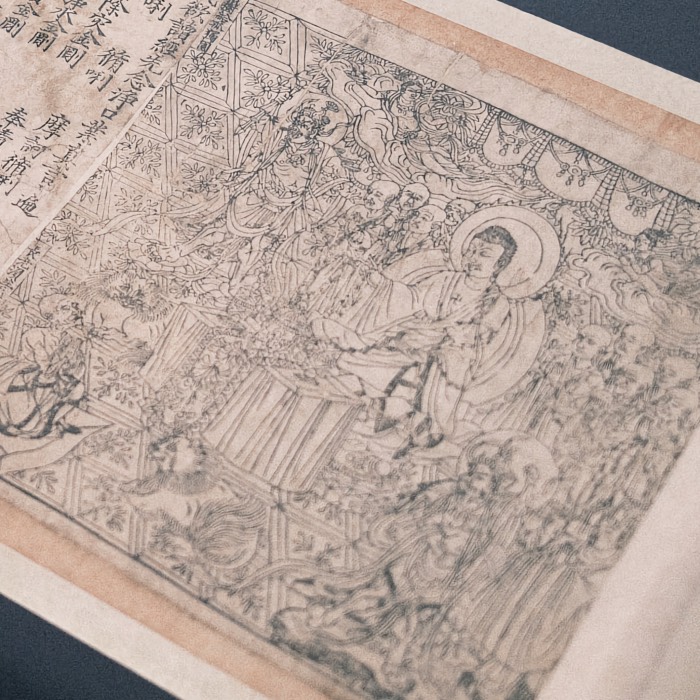

A page from a Song-era publication printed using a regular script style. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

References and further reading

- John DeFrancis, The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy, 1984, University of Hawaii Press

- Bernhard Karlgren, Schrift und Sprache der Chinesen, 2001, Springer, 2nd edition, ISBN: 3-540-42138-6

- S. Robert Ramsey, The Languages of China, 1987, Princeton University Press, 2nd edition, ISBN: 0-691-06694-9

- Norman, J., Chinese, 1988, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521296533

- Graham Thurgood, Randy J. LaPolla, The Sino-Tibetan Languages, 2020, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0367570453

- Demattè, Paola, The origins of Chinese writing, 2022, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-197-63576-6

- William H. Baxter, A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, 1992, Trends in Linguistics, Studies and monographs No. 64 Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN: 3-11-012324-X

- Ping Chen, Modern Chinese. History and Sociolinguistics, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521645720

- Wieger, L., Chinese Characters, 1965, Dover, ISBN: 0-486-21321-8

- Coulmas, F., Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis, 2003, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521787376

- Comrie, Bernard, The World’s Major Languages, 2018, Taylor & Francis Ltd., ISBN: 978-1138184824

- Baxter, W. H., & Sagart, L., Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199945375

- Pulleyblank, E. G., Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin, 1991, University of British Columbia Press, ISBN: 978-0774803663

- Boltz, William, The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system, 1994, American Oriental Society, ISBN: 978-0-940490-78-9

- Fortson, B. W., Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, 2010, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405188968

- Wilkinson, Endymion, Chinese History: A New Manual, 2013, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, Cambridge, Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN: 978-0-674-06715-8

- Wu, Teresa L., The Origin and Dissemination of Chinese Characters, 1990, Taipei: Caves Books, ISBN: 978-957-606-002-1

- Wikipedia article on the Chinese languageꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Sino-Tibetan languagesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the history of writingꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Chinese charactersꜛ and Written Chineseꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Chinese character radicalsꜛ

comments