Pali: Language of Buddha’s teachings

Pāli holds a distinguished position as the language of the Theravāda Buddhist canon, known as the Tipiṭaka or Pāli Canon. It serves not only as a vital linguistic link to early Buddhist teachings but also reflects the cultural and religious exchanges of ancient South Asia. Although Pāli is often referred to as a “dead” language, it continues to be studied, recited, and revered in Buddhist communities worldwide. In this article, we briefly explore the origins, development, and cultural significance of Pāli and its role in expressing and preserving Buddhist teachings.

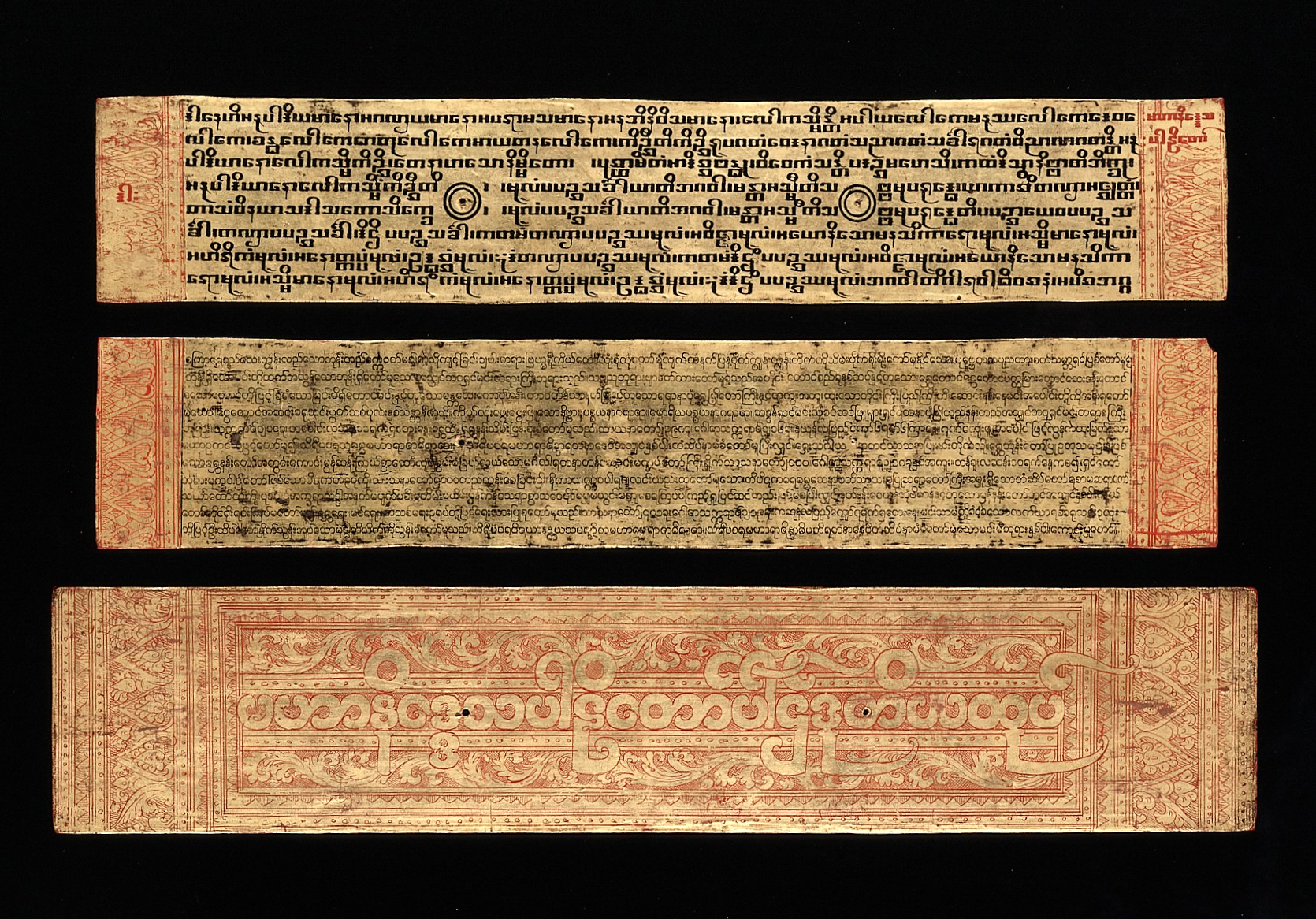

Burmese Kammavaca manuscript written in Pali using the Burmese script. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Burmese Kammavaca manuscript written in Pali using the Burmese script. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Origins and development of Pāli

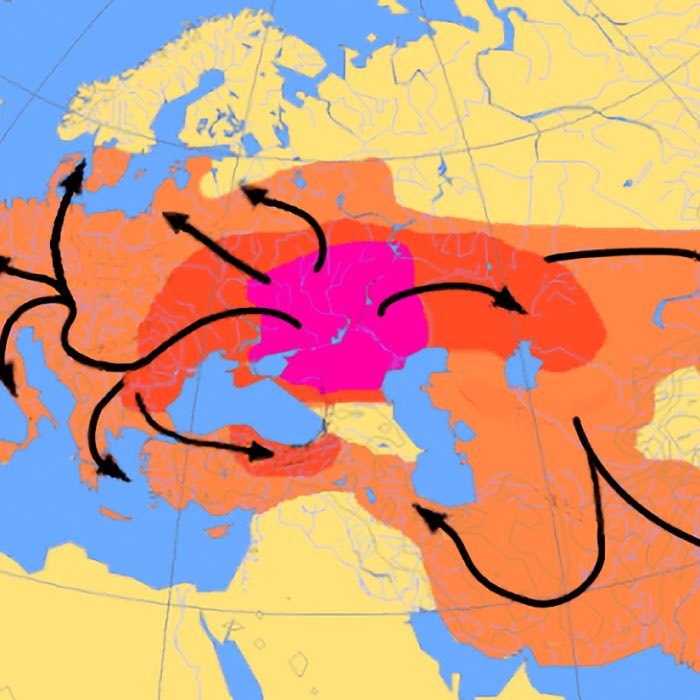

The origins of Pāli are intricately tied to the linguistic and cultural milieu of ancient India during the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE. Linguistically, Pāli belongs to the Middle Indo-Aryan stage of the Indo-European language family, closely related to Prakrit languages. It is widely regarded as a standardized and somewhat artificial dialect, possibly created or selected by early Buddhist communities for its simplicity and widespread comprehensibility.

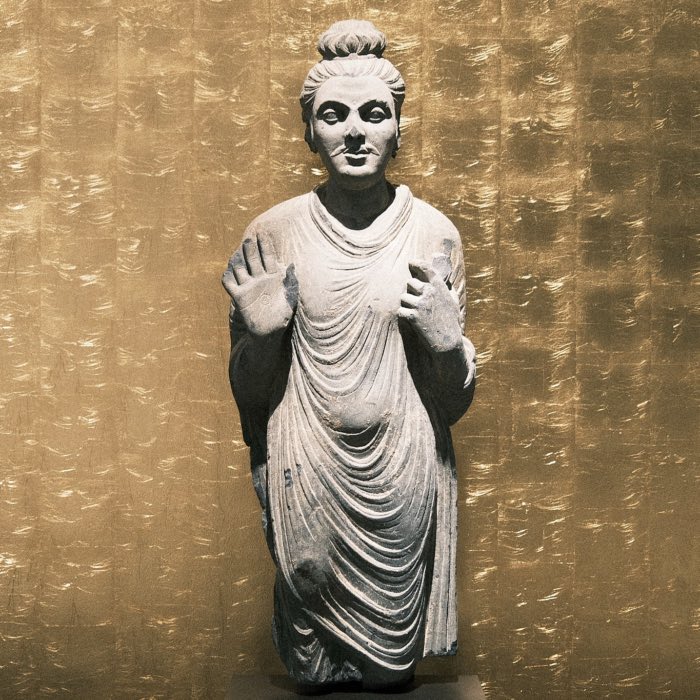

Pāli’s precise geographic and linguistic origins remain debated. While some scholars suggest that it originated in the Magadha region (modern-day Bihar, India), where Gautama Buddha lived and taught, others argue that it represents a composite dialect influenced by various vernaculars. The Buddha himself is believed to have spoken an early form of Magadhi Prakrit from the Magadha region (modern Bihar, India), advocating the use of local languages to convey his teachings rather than the elite language of Sanskrit. The Buddha’s insistence on teaching in vernacular languages, rather than the elite Sanskrit, reflects his commitment to accessibility and inclusivity, which is mirrored in Pāli’s development.

Magadha and other Mahajanapadas in the post-Vedic period, around 500 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Magadha and other Mahajanapadas in the post-Vedic period, around 500 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

By the time of the Buddhist councils, particularly the Third Council convened under Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, Pāli had become the established medium for preserving and disseminating the Buddha’s teachings. Its selection was likely driven by pragmatic considerations, ensuring the teachings could reach a broad audience while maintaining linguistic uniformity across monastic communities.

The role of Pāli in Buddhism

Pāli holds a central place in Theravāda Buddhism, where it serves multiple functions, including preservation, liturgical use, and doctrinal precision.

19th century Burmese Kammavācā (confession for Buddhist monks), written in Pali on gilded palm leaf. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

19th century Burmese Kammavācā (confession for Buddhist monks), written in Pali on gilded palm leaf. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

The Pāli Canon: Preserving the Buddha’s teachings

Pāli’s most significant contribution lies in its preservation of the Tipiṭaka, the foundational scripture of Theravāda Buddhism. Composed of three “baskets” (piṭakas), the Tipiṭaka encompasses the Vinaya Piṭaka (monastic rules), the Sutta Piṭaka (discourses of the Buddha), and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka (philosophical and doctrinal analyses).

The Tipiṭaka reflects a rich oral tradition, meticulously transmitted by monastic communities through recitation (bhāṇaka) and memorization before being written down, likely in Sri Lanka during the 1st century BCE. Pāli’s phonetic simplicity and grammatical regularity made it particularly well-suited for oral preservation, ensuring the accuracy of the teachings over centuries.

Liturgical and ritual use

In Theravāda Buddhist traditions, Pāli serves as the liturgical language for chanting and rituals. Texts like the Mahāparitta (Great Protection) and the Mangala Sutta are recited in Pāli during ceremonies, emphasizing the sanctity and continuity of the Buddha’s teachings. Chanting in Pāli is believed to confer spiritual benefits, creating a direct connection to the Buddha’s words.

Philosophical and doctrinal precision

Pāli’s linguistic structure supports the precise articulation of Buddhist doctrines. The language’s vocabulary is tailored to express nuanced philosophical concepts, such as anicca (impermanence), dukkha (suffering), and anattā (non-self). This precision has made Pāli indispensable for scholars and practitioners seeking to understand the original context of the Buddha’s teachings.

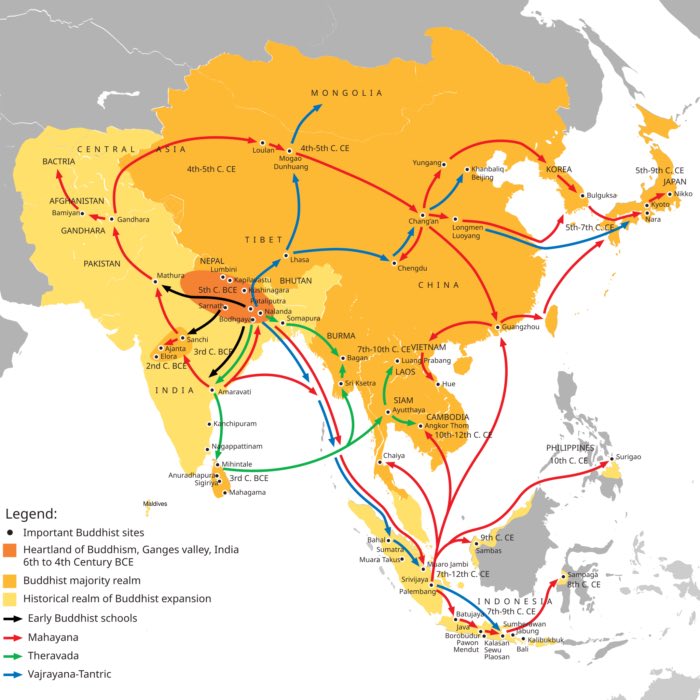

Spread of Pāli and its cultural influence

Ashoka’s missions and Pāli’s expansion

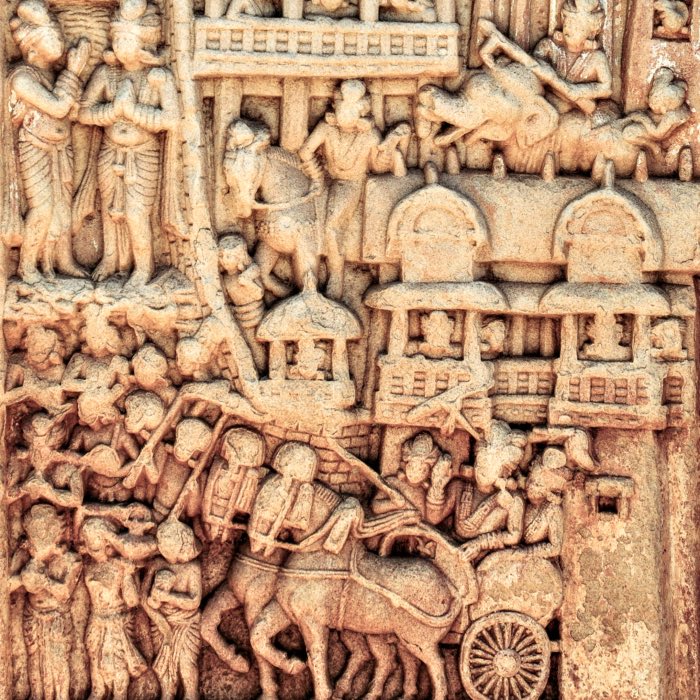

The expansion of Pāli as a canonical language is closely linked to the spread of Buddhism during the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. While Ashoka’s edicts were written in Brahmi script using regional Prakrit dialects, not Pāli itself, his support for Buddhism laid the groundwork for Pāli’s later prominence. Ashoka’s establishment of monastic institutions and his missionary efforts – such as the mission to Sri Lanka led by his son Mahinda – introduced Buddhism to new regions.

Buddhist embassies at the time of Ashoka. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Buddhist embassies at the time of Ashoka. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In Sri Lanka, the Theravāda tradition adopted Pāli as the medium for its scriptures. The Mahāvaṃsa (Great Chronicle), a historical text written in Pāli, chronicles the island’s adoption of Buddhism and its role in preserving the Tipiṭaka. From Sri Lanka, Pāli spread to Southeast Asia, where it influenced local languages and cultures. Thus, Ashoka’s promotion of Buddhism indirectly facilitated the spread of Pāli as the liturgical and scholarly language of Theravāda Buddhism.

Linguistic and literary influence

Pāli’s influence extended beyond the Buddhist canon, enriching the lexicons of Southeast Asian languages such as Sinhala, Burmese, Thai, and Khmer. Many Pāli terms related to religion, philosophy, and governance were adopted into these languages, shaping their cultural and intellectual landscapes.

Burmese-Pali manuscript copy of the Buddhist text Mahaniddesa. Shown are three different types of Burmese script, medium square (top), round (centre) and outline round in red lacquer from the inside of one of the gilded covers (bottom). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

For instance, in Thailand, Pāli remains a key component of Buddhist education, with monastic schools teaching Pāli grammar and literature. Similarly, in Myanmar, the study of Pāli is integral to monastic training, ensuring the continuity of Buddhist traditions.

The decline and revival of Pāli

Although Pāli’s use as a spoken language declined over time, its role as a liturgical and scholarly language persisted. In the 19th and 20th centuries, efforts to revive Pāli studies emerged, driven by both Buddhist reform movements and Western academic interest. Today, Pāli is taught in universities and monastic institutions worldwide, fostering a renewed appreciation for its linguistic and cultural heritage.

Writing systems and regional adaptations

Pāli, like Sanskrit, was initially transmitted orally, relying on the meticulous memorization and recitation techniques of monastic communities. The oral tradition ensured the preservation of the Buddha’s teachings for centuries before they were committed to writing. The first written records of Pāli likely appeared in Sri Lanka around the 1st century BCE.

Brāhmī: The script of the Pāli Canon

The earliest written Pāli texts, including the Tipiṭaka (Pāli Canon), were inscribed using the Brāhmī script in Sri Lanka. Brāhmī’s straightforward design made it well-suited for recording the voluminous Buddhist scriptures. This transition marked a significant milestone in preserving the Buddha’s teachings for posterity.

A Major Pillar Edict of Ashoka written in the Brahmi script, 3rd century BCE, found in Lauriya Araraj, Bihar, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 3.0)

Regional adaptations

As Pāli spread to Southeast Asia, it was transcribed into various regional scripts, each tailored to local linguistic and cultural contexts:

- Sinhala Script: In Sri Lanka, the Sinhala script became the primary medium for Pāli texts. This script evolved directly from Brāhmī and remains central to Buddhist scholarship in Sri Lanka.

- Burmese Script: In Myanmar, Pāli texts were adapted to the Burmese script, facilitating the integration of Theravāda Buddhism into Burmese culture.

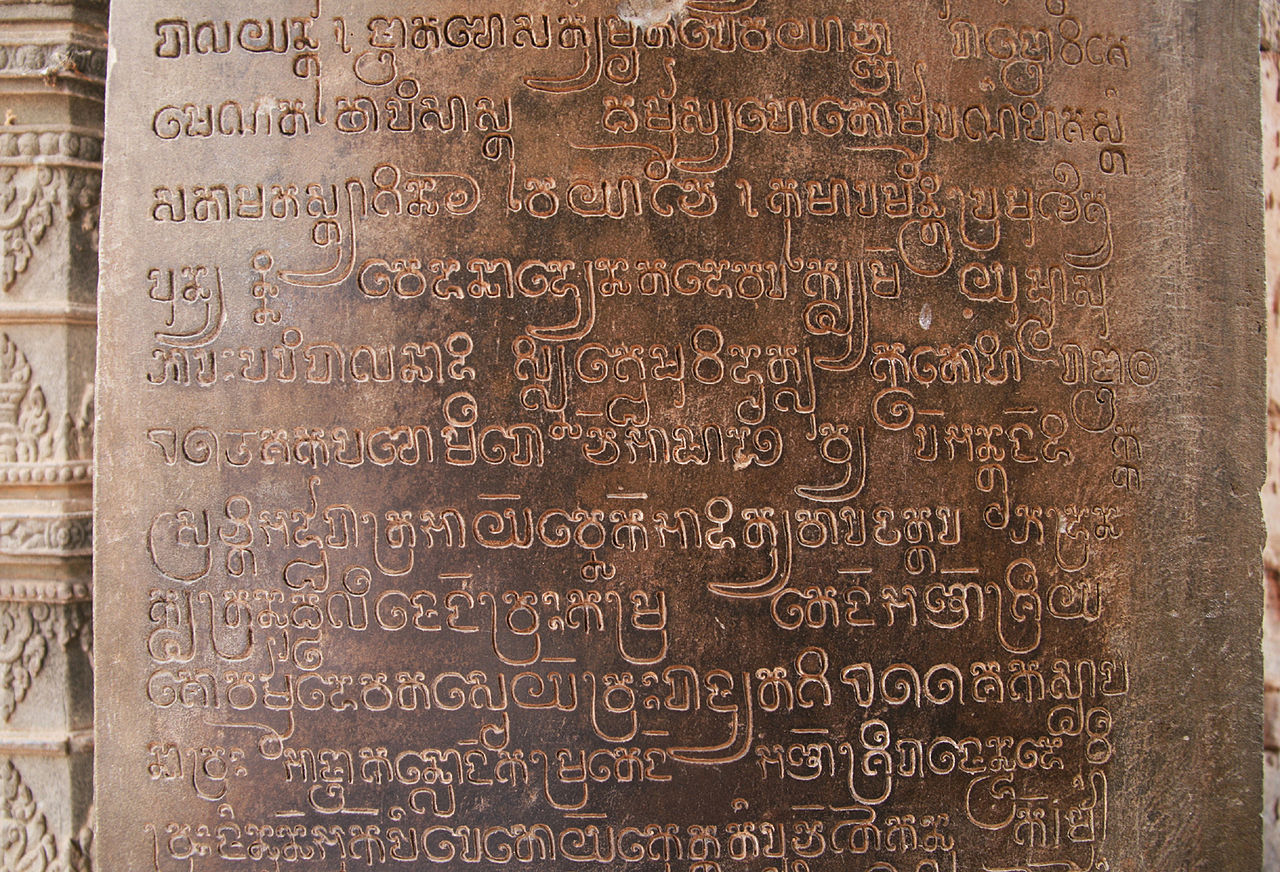

- Khmer Script: In Cambodia, Pāli was transcribed into the Khmer script, which similarly derived from Brāhmī.

- Thai Script: In Thailand, Pāli is written using the Thai script, where it continues to play a vital role in Buddhist education and liturgy.

Unlike Sanskrit, which is often associated with Devanāgarī in modern times, Pāli does not have a single standardized script. Instead, its use of diverse scripts reflects the language’s adaptability and its integration into various Theravāda Buddhist traditions.

The Ram Khamhaeng Inscription, the oldest inscription using proto-Thai script, Bangkok National Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 1.0)

Comparison between Pāli and Sanskrit

Pāli and Sanskrit represent two distinct linguistic traditions within the broader context of ancient Indian languages. While Sanskrit served as the language of elite culture and religious scholarship, Pāli emerged as a vernacular dialect tailored to convey the Buddha’s teachings to a wider audience. A comparison of Pāli and Sanskrit reveals differences in phonetics, grammar, vocabulary, and cultural roles.

Linguistic origins and status

Pāli and Sanskrit share a common ancestry as members of the Indo-European language family but represent different stages of linguistic evolution. Sanskrit, specifically Classical Sanskrit, is a highly formalized language, codified by Pāṇini in his Aṣṭādhyāyī. It was the language of the elite, used in religious, literary, and scholarly contexts. In contrast, Pāli is derived from the vernacular Prakrits and represents a Middle Indo-Aryan language, chosen for its accessibility to a broader audience.

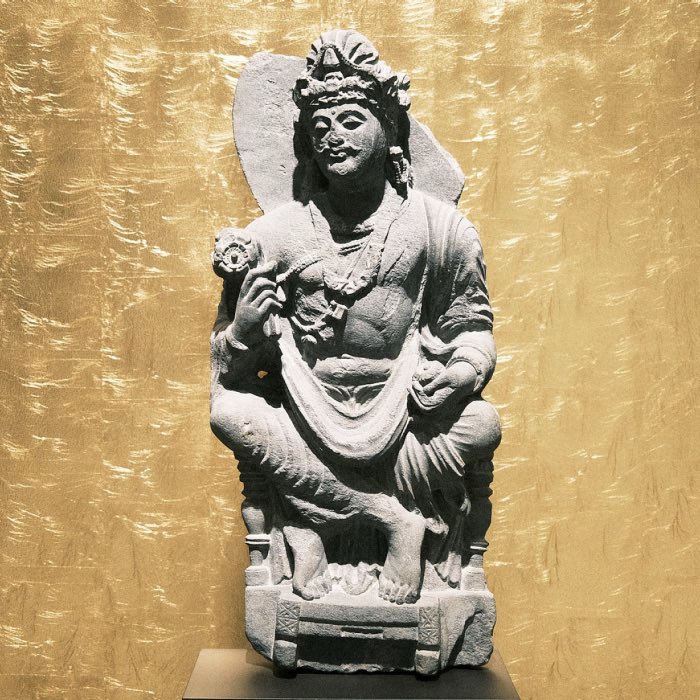

While Sanskrit retained its status as the liturgical and scholarly language of Hinduism and Mahāyāna Buddhism, Pāli became the sacred language of Theravāda Buddhism. This division reflects their respective roles: Sanskrit aimed to preserve the high culture of ancient India, whereas Pāli sought to democratize religious teachings.

Phonetic and grammatical differences

Phonetically, Pāli simplifies many of the sounds found in Sanskrit. For instance, aspirated consonants like bh and dh are retained in Sanskrit but often become unaspirated in Pāli. Sanskrit’s consonant clusters are also reduced in Pāli for ease of pronunciation (kṣetra in Sanskrit becomes ketta in Pāli).

The following table highlights some Sanskrit and Pāli corresponding words, illustrating their phonetic and morphological adaptations:

| Sanskrit | Pāli | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| dharma | dhamma | teaching, law |

| anitya | anicca | impermanent |

| anātman | anattā | non-self |

| duḥkha | dukkha | suffering |

| śūnya | suñña | emptiness |

| kṣetra | ketta | field |

| vṛkṣa | rukkha | tree |

| nāga | nāga | serpent, deity |

| yajña | yañña | sacrifice |

| mārga | magga | path |

| aṣṭa | aṭṭha | eight |

| śrāvaka | sāvaka | disciple |

| nirvāṇa | nibbāna | liberation, enlightenment |

| dhyāna | jhāna | meditation |

| bodhisattva | bodhisatta | enlightened being |

| arhati | arahant | worthy one, saint |

| saṃgha | saṅgha | monastic community |

| cakra | cakka | wheel |

| citta | citta | mind |

| vijñāna | viññāṇa | consciousness |

Grammatically, Sanskrit is more complex, with eight cases for nouns and a rich system of verb conjugations. Pāli, while retaining the fundamental Indo-Aryan grammatical structure, simplifies these forms. For example, Sanskrit’s dual number is largely absent in Pāli, reflecting its more streamlined syntax.

Vocabulary and usage

Many Pāli words are directly borrowed from or influenced by Sanskrit, though often adapted to its simpler phonology. For example, the Sanskrit word dharma becomes dhamma in Pāli. However, Pāli’s vocabulary reflects its emphasis on conveying the teachings of the Buddha, with terminology tailored to Buddhist philosophy.

In terms of usage, Sanskrit was primarily used for composing complex philosophical texts, hymns, and epics, while Pāli focused on preserving the Buddha’s teachings and making them accessible through oral transmission and recitation.

Cultural and religious roles

The roles of Pāli and Sanskrit in their respective traditions illustrate their unique contributions. Sanskrit’s association with Hinduism, Jainism, and Mahāyāna Buddhism underscores its versatility and widespread influence. Pāli’s role is more narrowly focused but no less significant, as it preserved the earliest Buddhist canon and became a cornerstone of Theravāda practice and philosophy.

Despite these differences, both languages share a deep interconnectedness, reflecting the rich linguistic and cultural heritage of ancient India.

Conclusion

Pāli’s legacy endures not only in the preservation of early Buddhist teachings but also in its ongoing relevance to Buddhist practice and scholarship. As the language of the Tipiṭaka, Pāli provides a direct link to the historical Buddha and his teachings, offering insights into the philosophical and ethical foundations of Buddhism.

The study of Pāli also bridges cultural and historical divides, connecting contemporary practitioners and scholars to the rich heritage of South and Southeast Asia. Through its phonetic elegance, grammatical precision, and doctrinal significance, Pāli continues to inspire devotion, reflection, and intellectual inquiry, affirming its place as one of humanity’s great linguistic and cultural treasures.

References and further reading

- Gethin, R., The Foundations of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192892232

- Oskar von Hinüber, A Handbook of Pali Literature, 2000, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 978-3110167382

- Oskar von Hinüber, Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien, 1990, Franz Steiner Verlag

- Wilhelm Geiger, Pali Literature and Language, 1996, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN: 978-8121507165

- Asha Das, The Glimpses of Pali Literature, 2004, Punthi Pustak, ISBN: 978-8186791257

- R. Webb, Bhikkhu Nyanatusita, An Analysis of the Pali Canon: And a Reference Table of Pali Literature, 2012, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka, ISBN: 978-9552403767

- Collins, S., Selfless Persons: Imagery and Thought in Theravada Buddhism, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521397261

- Warder, A. K., Indian Buddhism, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120817418

- Eugène Burnouf, Katia Buffetrille, Donald S. Lopez Jr., Introduction to the History of Indian Buddhism, 2015, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226269689

- Richard Salomon, The Buddhist Literature of Ancient Gandhara: An Introduction with Selected Translations, 2018, Wisdom Publications, ISBN: 978-1614291688

- Conze, E., Buddhist Scriptures, 1958, Penguin Classics, ISBN: 978-0140440881

- Annette Wilke, Oliver Moebus, Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, 2011, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 978-3-11-024003-0

- Bühler, Georg, On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet, 1898, Strassburg K.J. Trübner

- Keay, John, India: A History, 2000, Grove Press, ISBN: 978-0-8021-3797-5

- Masica, Colin, The Indo-Aryan Languages, 1993, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0-521-29944-2

- Falk, Harry, Aśokan Sites and Artefacts: A Source-book with Bibliography, 2006, Von Zabern, ISBN_ 978-3-8053-3712-0

- Nikam, N. A., McKeon, Richard, The Edicts of Aśoka, 1959, University of Chicago Press

- Olivelle, Patrick, Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King, 2024, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0-300-27490-5

- Olivelle, Patrick, Leoshko, Janice, Ray, Himanshu Prabha, Reimagining Asoka: Memory and History; 2012, Oxford University Press India, ISBN: 978-0-19-807800-5

- Mahinda Deegalle, Popularizing Buddhism: Preaching as Performance in Sri Lanka, 2006, State University of New York Press, 2006

comments