Sanskrit: Sacred language of ancient India

Sanskrit, one of the oldest attested languages of the Indo-European family, occupies a unique position in the linguistic, cultural, and religious history of humanity. Renowned for its systematic grammar and immense literary corpus, Sanskrit offers invaluable insights into the evolution of languages, the spread of Indo-European peoples, and the intellectual traditions of South Asia. In this post, we briefly explore the origins, evolution, and significance of Sanskrit as a sacred language and as a vehicle for profound philosophical and literary expression.

The word ‘Sanskrit’ in the nominative singular in Devanagari script; writing and reading direction is from left to right. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Sanskrit and the Indo-European language family

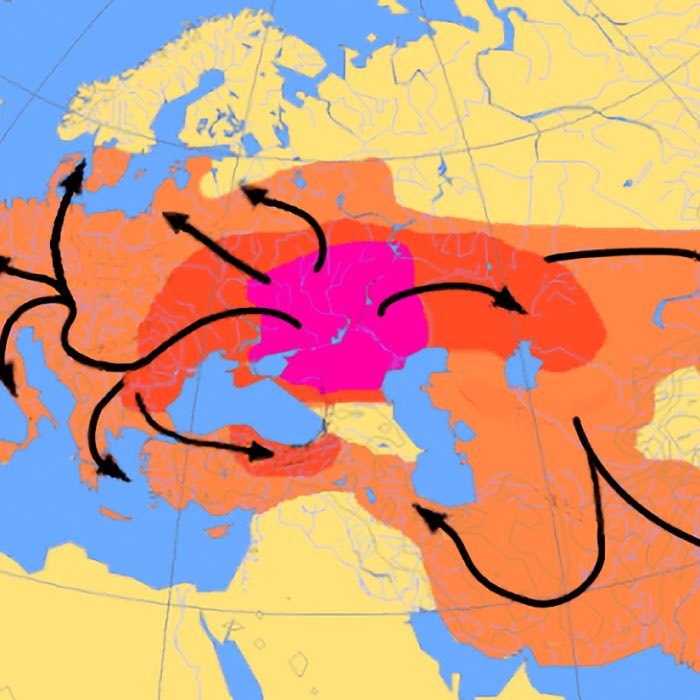

Sanskrit, specifically its earliest form, Vedic Sanskrit, is a member of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Alongside Avestan and Old Persian, it represents the easternmost expansion of Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The meticulous preservation of Sanskrit through oral traditions and its codification in the seminal grammar of Pāṇini has rendered it one of the most thoroughly documented ancient languages.

Language families of the world, Indo-European in yellow. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Language families of the world, Indo-European in yellow. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The linguistic ties between Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages became evident in the late 18th century, when Sir William Jones observed systematic correspondences between Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. For example, the Sanskrit word pitṛ (father) corresponds to Latin pater and Greek patēr, all derived from the PIE root pətér. Such cognates highlight shared origins and sound changes that shaped these languages over millennia.

Evolution and spreading of sanskrit

Sanskrit’s development and diffusion reflect the cultural and religious dynamics of ancient India and beyond. From its origins in the Vedic period to its spread across South and Southeast Asia, Sanskrit played a pivotal role in shaping literary, religious, and philosophical traditions.

Vedic Sanskrit

The earliest form of Sanskrit, Vedic Sanskrit, emerged around 1500 BCE and is preserved in the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. This language exhibits features of early Indo-Iranian, such as the preservation of PIE aspirated stops (bʰ, dʰ, gʰ) and complex vowel alternations (ablaut). Vedic Sanskrit was primarily an oral language, and its phonetic precision was crucial for preserving sacred hymns across generations.

Classical Sanskrit

By the mid-1st millennium BCE, Vedic Sanskrit evolved into Classical Sanskrit, as codified in Pāṇini’s grammar (Aṣṭādhyāyī). Pāṇini’s work formalized the language’s phonetics, morphology, and syntax, setting a standard for its use in literature and religious texts. Classical Sanskrit became the language of scholarship, epic poetry, and religious discourse, transcending regional dialects to become a pan-Indian lingua franca.

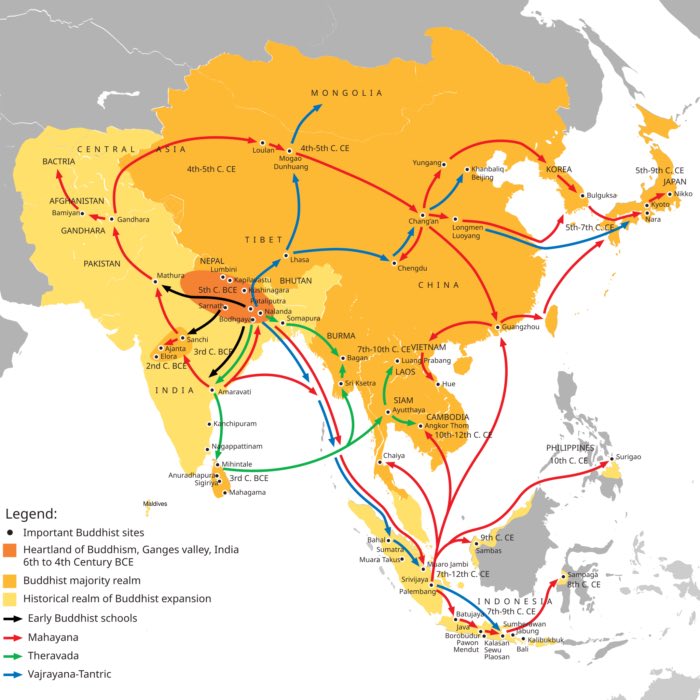

Spread beyond India

Sanskrit’s influence extended beyond the Indian subcontinent through trade, migration, and the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism. In Southeast Asia, Sanskrit loanwords enriched local languages, and inscriptions in Sanskrit are found in Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand. Buddhist missionaries carried Sanskrit texts to Central Asia, China, and Tibet, fostering cultural and linguistic exchanges along the Silk Road.

Phonetics and grammatical structure

Phonetics

Sanskrit’s phonetic system is one of the most sophisticated in the Indo-European family, reflecting its oral tradition and the importance of precise articulation in Vedic rituals. It preserves PIE consonants, including aspirated stops and labiovelars, albeit with some transformations. For instance, PIE *gʷ* became j in Sanskrit (e.g., PIE *gʷén* > Sanskrit janá- ‘person’).

The vowel system of Sanskrit, derived from PIE, exhibits both short and long vowels, diphthongs, and a systematic use of vowel gradation (ablaut) to indicate grammatical and semantic distinctions. For example, the root *vid-* (‘to know’) alternates as *ved-* in the present tense (veda: ‘he knows’) and *vid-* in the infinitive (viditum: ‘to know’).

Grammatical structure

Sanskrit is a highly inflectional language, preserving the case system of PIE. It uses eight cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative, locative, instrumental, and vocative) to mark noun roles, along with three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter) and three numbers (singular, dual, plural). Verbs are conjugated for tense, mood, voice, person, and number, reflecting the rich morphology of PIE.

The use of compounds (samāsa) is a hallmark of Sanskrit, enabling concise expressions of complex ideas. For example, bhagavad-gītā (‘Song of the Lord’) combines bhagavad- (‘Lord’) and gītā (‘song’). This feature parallels compounding in Greek and other Indo-European languages, underscoring a shared grammatical heritage.

Similarities with Greek and Latin

Sanskrit shares numerous cognates with other Indo-European languages. In the following, we compare Sanskrit with Greek and Latin to illustrate these connections and the divergent developments that shaped each language.

Cognates

Sanskrit shares numerous cognates with Greek and Latin, illustrating their common PIE ancestry. Words for fundamental concepts, such as kinship terms, natural elements, and numbers, exhibit systematic correspondences:

- Sanskrit mātṛ (‘mother’) ~ Latin mater ~ Greek mētēr.

- Sanskrit saptá (‘seven’) ~ Latin septem ~ Greek hepta.

- Sanskrit agní (‘fire’) ~ Latin ignis ~ Greek pyr (with divergent evolution).

Sound changes

The comparison of Sanskrit with Greek and Latin reveals predictable sound changes from PIE. For instance, PIE palatovelars (kʷ, gʷ) were retained as labials in Latin (quod: ‘what’) but became velars or plain stops in Sanskrit (kas: ‘who’). Similarly, PIE voiced aspirates (bʰ, dʰ) remained in Sanskrit (bʰarati: ‘he carries’) but became unaspirated in Greek (phérō: ‘I carry’) and Latin (ferō: ‘I carry’).

Grammatical correspondences

The inflectional systems of Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin share striking parallels. All three languages use declensions and conjugations derived from PIE to indicate grammatical relations. For example:

- Sanskrit devasya (‘of the god’) ~ Latin dei ~ Greek theou (genitive singular).

- Sanskrit dattam (‘given’) ~ Latin datum ~ Greek dedomenon (past participle).

Such correspondences highlight the shared structural framework of these languages, while their divergences reflect independent developments.

Sanskrit in sacred texts

Sanskrit is unparalleled in its association with sacred literature, serving as the vehicle for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain texts.

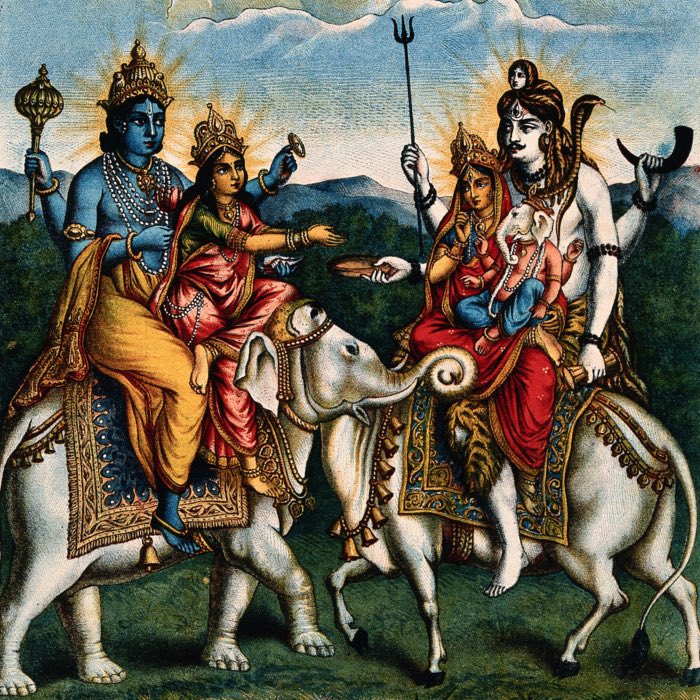

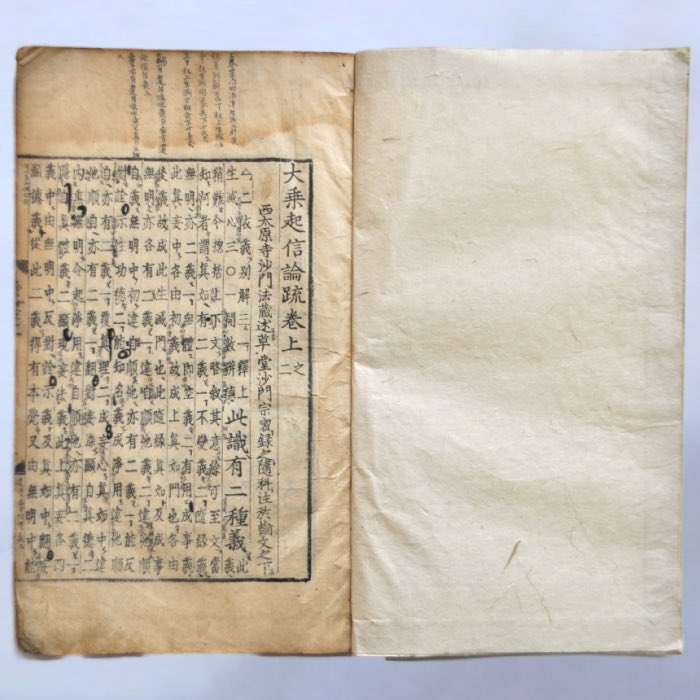

Religious text in Sanskrit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Religious text in Sanskrit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Hinduism

In Hinduism, Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, Upanishads, and epics like the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa. These texts articulate philosophical concepts, rituals, and moral narratives central to Hindu tradition. The Bhagavad Gītā, a portion of the Mahābhārata, remains a cornerstone of Hindu spiritual discourse.

The Vedas and the early religious canon

Sanskrit’s association with the sacred begins with the Vedas, the oldest texts of Hinduism and among the earliest religious compositions in human history. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the Rigveda (circa 1500–1200 BCE) is the earliest of the four Vedas, followed by the Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda. These texts encompass hymns, rituals, and philosophical discourses central to Vedic religion, emphasizing themes of cosmology, divine order (ṛta), and sacrifice.

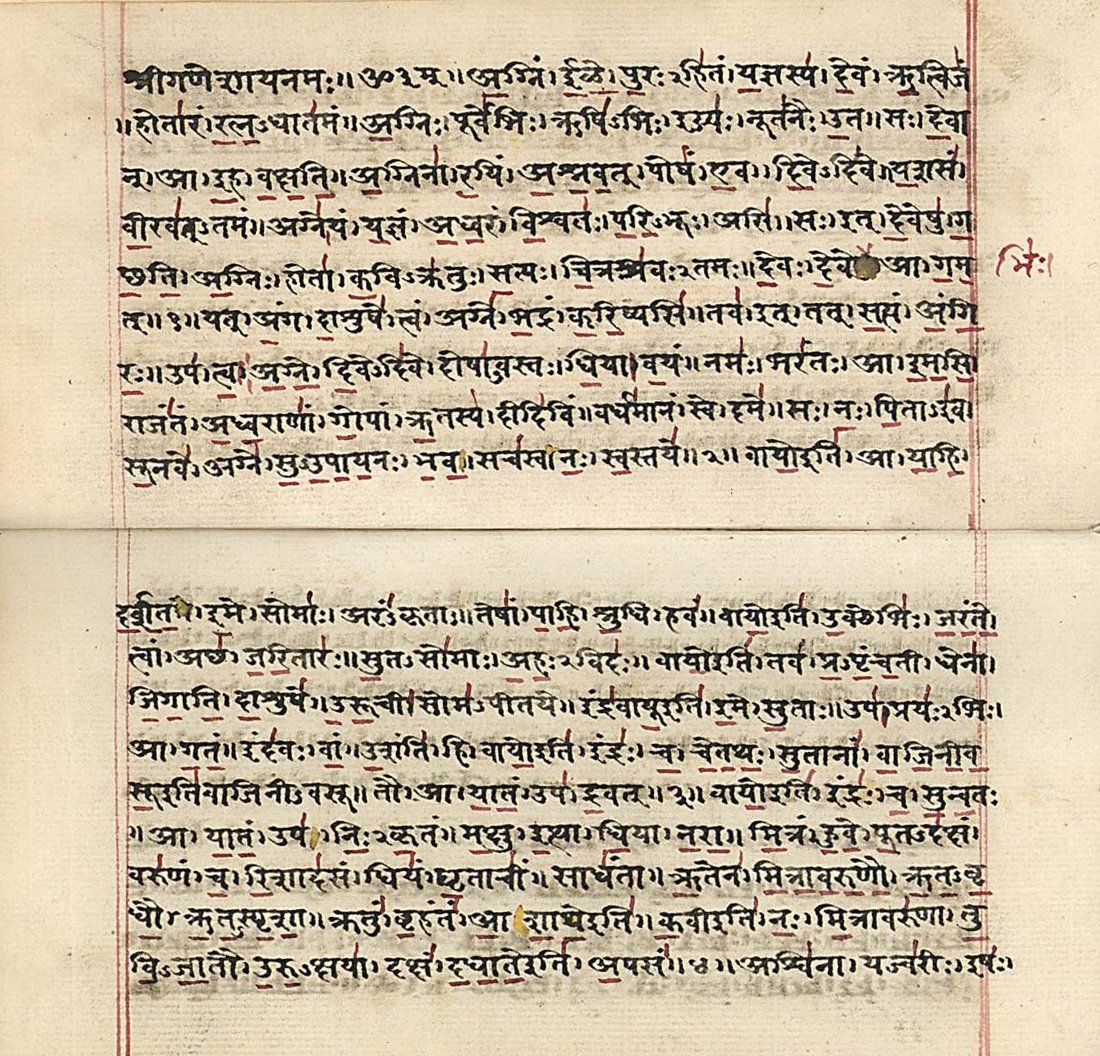

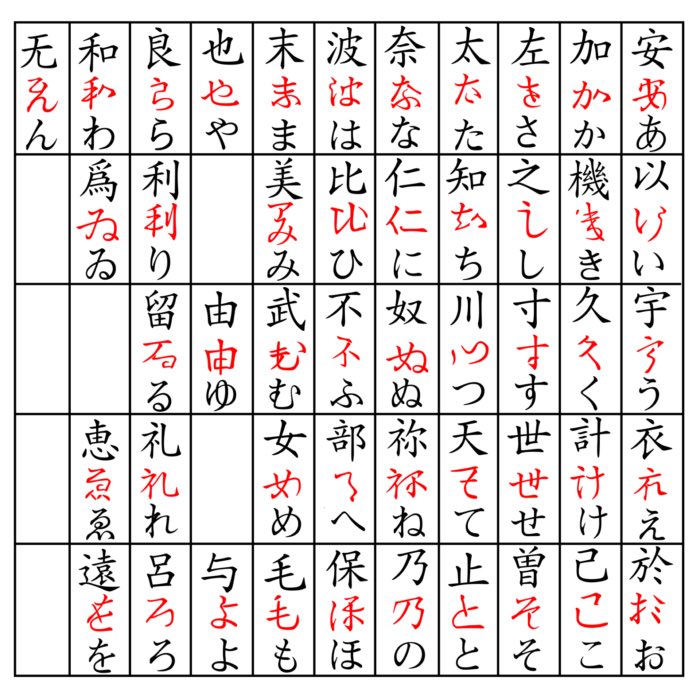

Rigveda (padapatha) manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century. The red horizontal and vertical lines mark low and high pitch changes for chanting. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Rigveda (padapatha) manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century. The red horizontal and vertical lines mark low and high pitch changes for chanting. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The precise oral transmission of the Vedas through recitation (śruti) ensured their preservation over millennia. The linguistic complexity and structure of Sanskrit made it uniquely suited for this purpose, as its phonetic precision and grammatical rules facilitated accurate memorization and reproduction.

Post-Vedic texts and philosophical works

Sanskrit continued to be the medium for Hindu religious and philosophical texts long after the Vedic period. The Upanishads (circa 800–300 BCE) transitioned from ritual-centric teachings to philosophical explorations of the self (ātman), ultimate reality (Brahman), and liberation (moksha). These texts laid the foundation for Indian metaphysics and were instrumental in shaping subsequent Hindu thought.

The Mahabharata and Ramayana, two epic Sanskrit texts, provided narratives that combined theological insights with cultural and moral guidance. The Bhagavad Gita, embedded within the Mahabharata, is a cornerstone of Hindu philosophy, presenting a synthesis of devotion, knowledge, and selfless action.

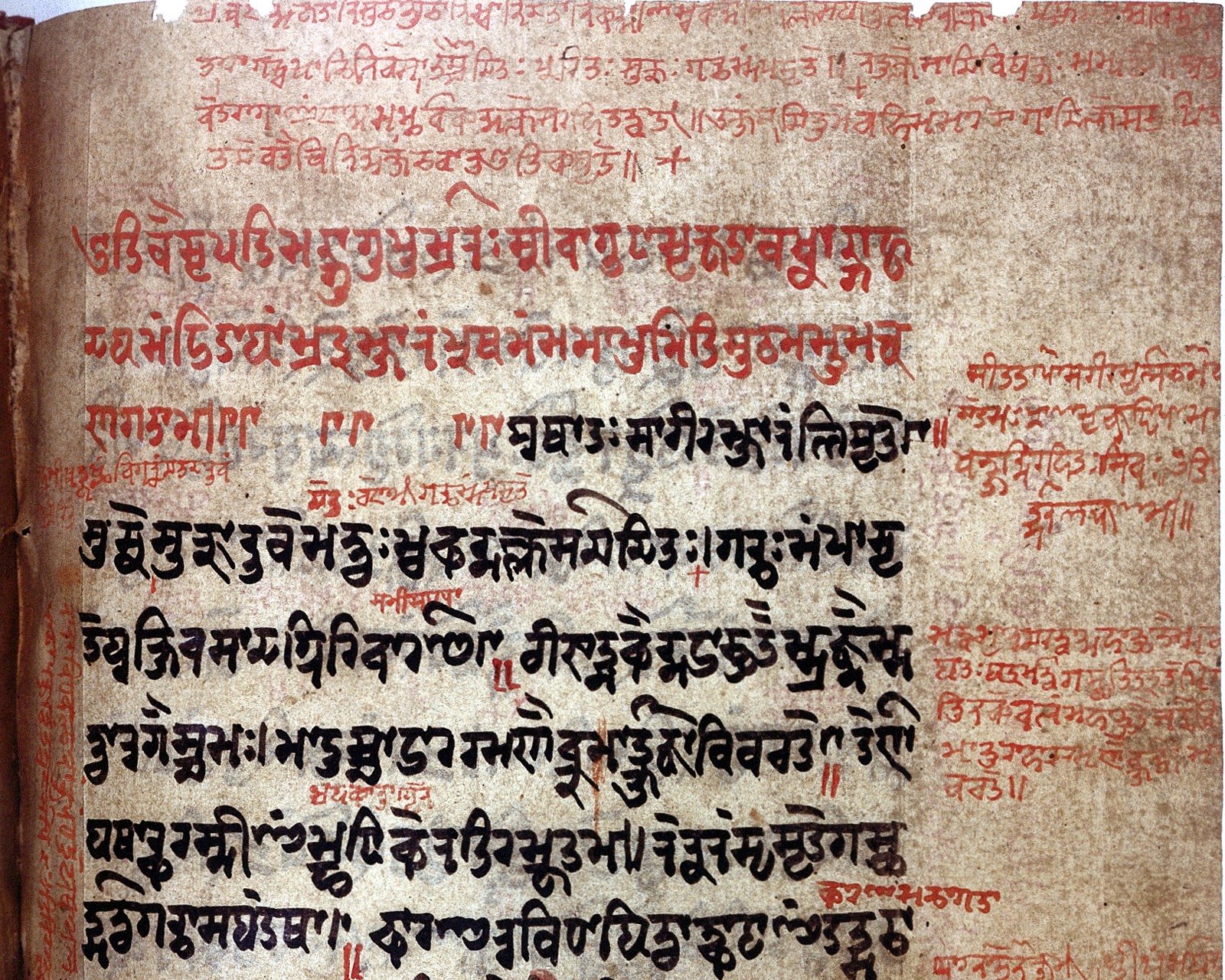

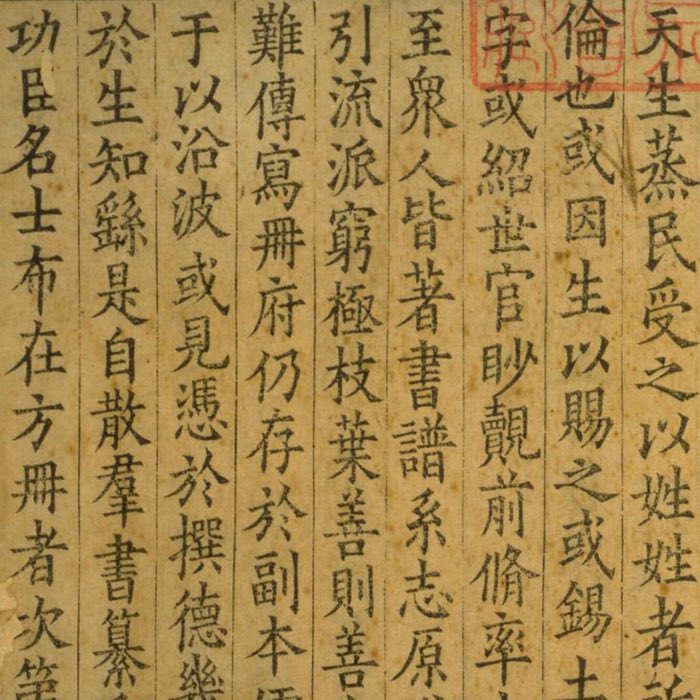

Text of colophon from manuscript on medicine, written in Sanskrit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Text of colophon from manuscript on medicine, written in Sanskrit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

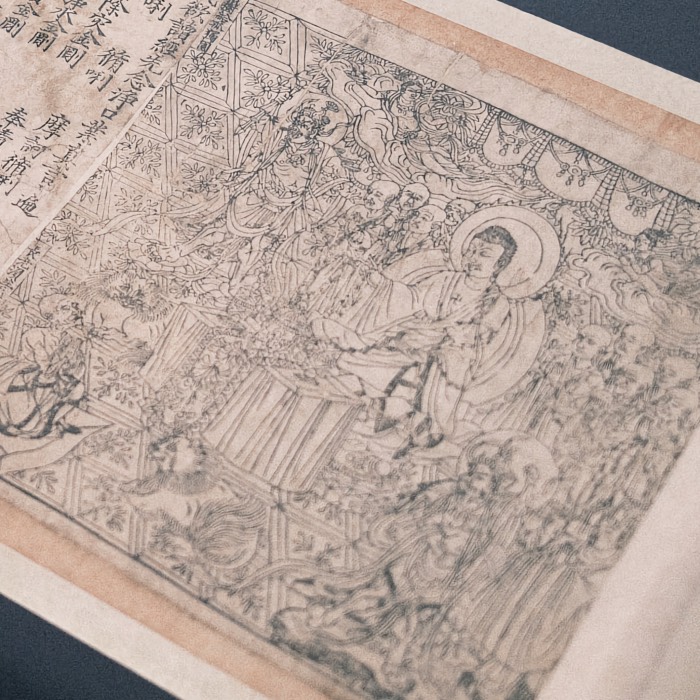

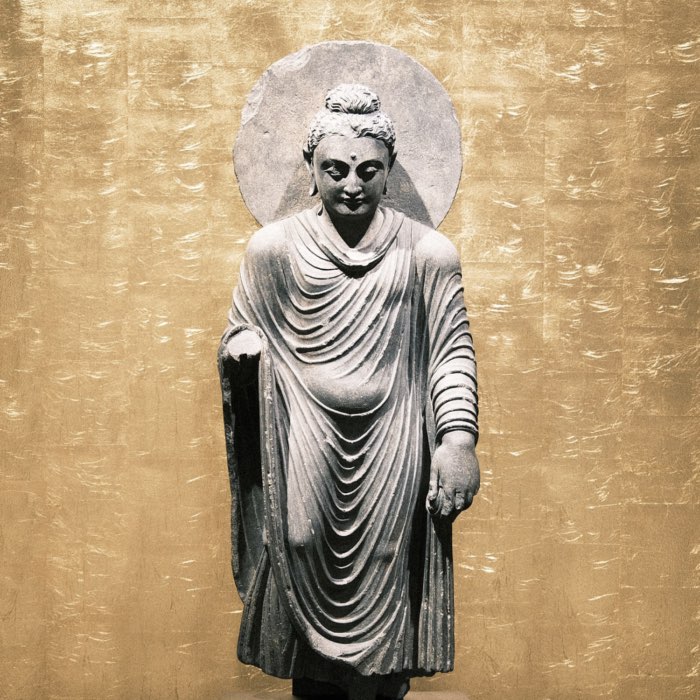

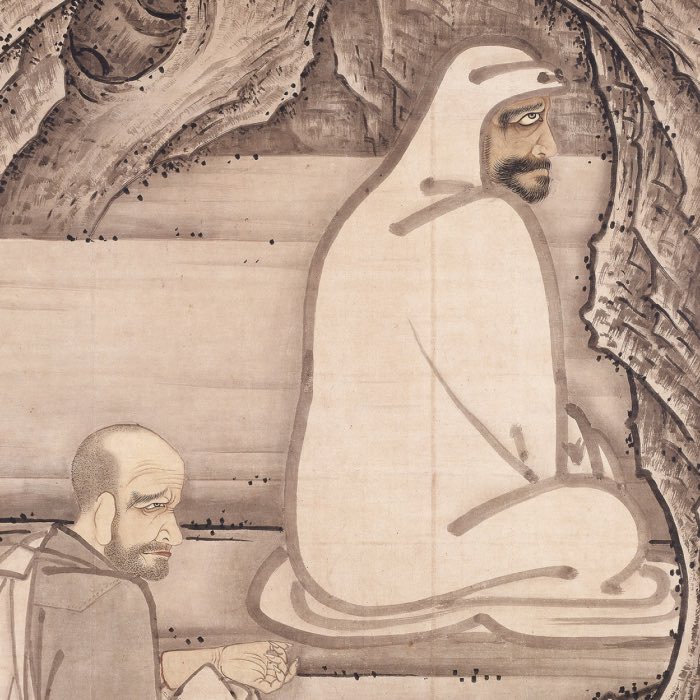

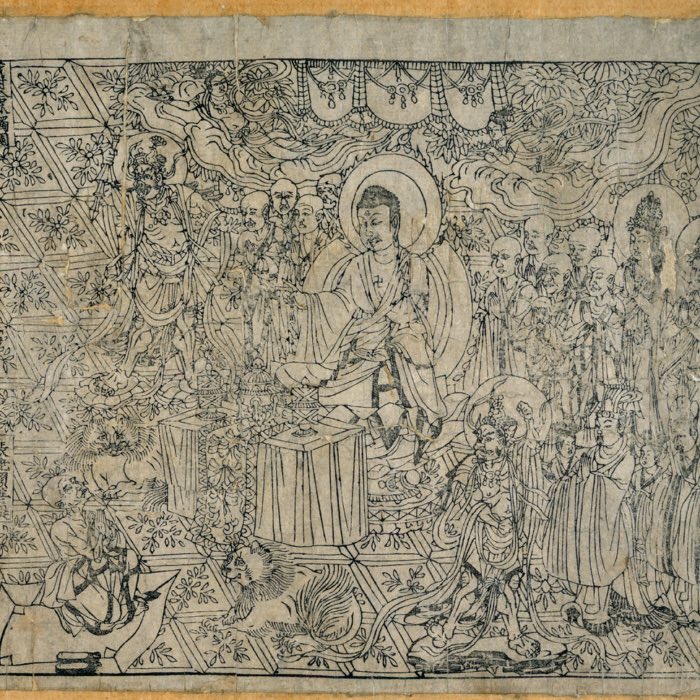

Buddhism

Buddhism – particularly in Mahāyāna traditions – adopted Sanskrit as a sacred language alongside Pāli, a language closely related to Sanskrit but simpler in grammar and structure. Texts like the Heart Sutra and the Lotus Sutra were composed in Sanskrit, facilitating their transmission to China, Tibet, and beyond. Sanskrit Buddhist literature contributed to the development of Buddhist philosophy, linguistics, and art across Asia.

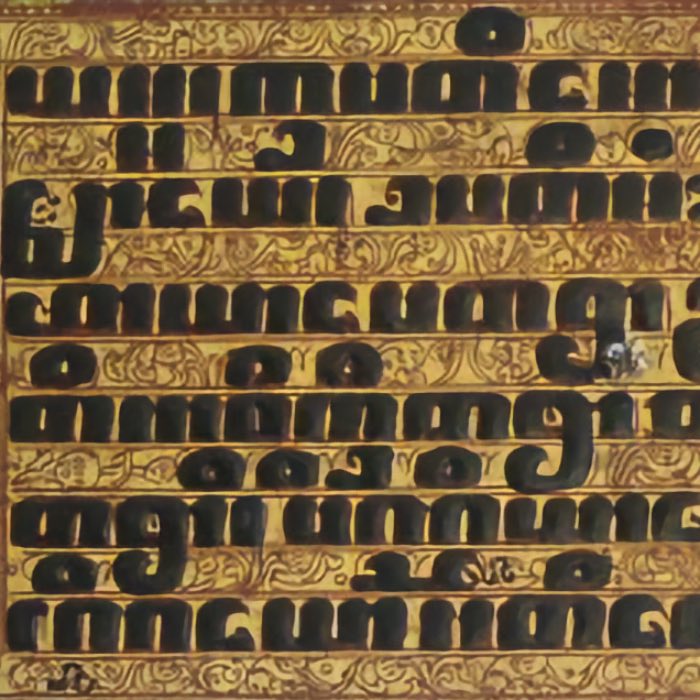

Sanskrit manuscript of the Heart Sūtra, written in the Siddhaṃ script. This original copy may be the earliest extant Sanskrit manuscript dated to the 7th–8th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sanskrit manuscript of the Heart Sūtra, written in the Siddhaṃ script. This original copy may be the earliest extant Sanskrit manuscript dated to the 7th–8th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Transition to Sanskrit

The earliest Buddhist scriptures, preserved in the Pāli Canon (Tipitaka), were composed in Pāli. However, as Buddhism expanded and engaged with diverse cultures and intellectual traditions, Sanskrit’s prestige as a literary and scholarly language – like Greek in the Roman Empire and Latin in the medieval West – led to its adoption for Buddhist works, particularly in the Mahāyāna tradition.

By the 2nd century CE, Sanskrit had become the primary language for Mahāyāna Buddhist texts. These texts, known as the Sanskrit Buddhist Canon, include seminal works such as the Lotus Sutra (Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra), the Heart Sutra (Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya), and the Avatamsaka Sutra (Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra). Sanskrit’s rich vocabulary and grammatical precision allowed Buddhist thinkers to articulate intricate philosophical concepts, such as emptiness (śūnyatā) and dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda), with remarkable clarity.

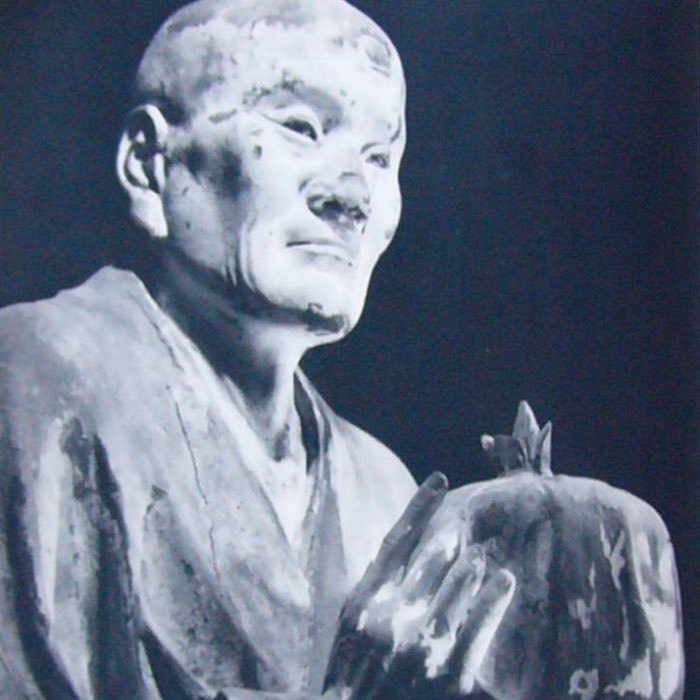

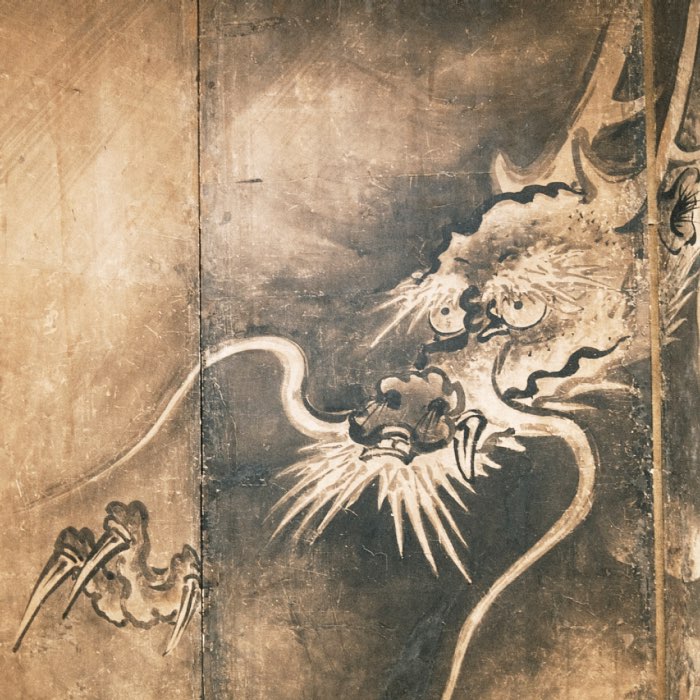

A reproduction of the above palm-leaf manuscript in Siddham script, originally held at Hōryū-ji, Japan; now located in the Tokyo National Museum at the Gallery of Hōryū-ji Treasure. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

A reproduction of the above palm-leaf manuscript in Siddham script, originally held at Hōryū-ji, Japan; now located in the Tokyo National Museum at the Gallery of Hōryū-ji Treasure. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Philosophical treatises and commentaries

Sanskrit was also the medium for the works of prominent Buddhist philosophers such as Nāgārjuna, Asaṅga, and Vasubandhu. Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way) is a foundational text of the Madhyamaka school, written in concise and rigorous Sanskrit verse. Similarly, Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośa (Treasury of Abhidharma) systematically analyzes Buddhist metaphysics and psychology.

Spread to Central and East Asia

Sanskrit’s role in Buddhist literature was instrumental in the transmission of Buddhist teachings beyond India. Texts written in Sanskrit were translated into Chinese, Tibetan, and other languages, often by scholar-monks who traveled along the Silk Road. These translations facilitated the spread of Buddhist philosophy and practices to Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia, ensuring the global influence of Buddhist thought.

Sanskrit language’s historical presence has been attested in many countries. The evidence includes manuscript pages and inscriptions discovered in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Central Asia. These have been dated between 300 and 1800 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sanskrit language’s historical presence has been attested in many countries. The evidence includes manuscript pages and inscriptions discovered in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Central Asia. These have been dated between 300 and 1800 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

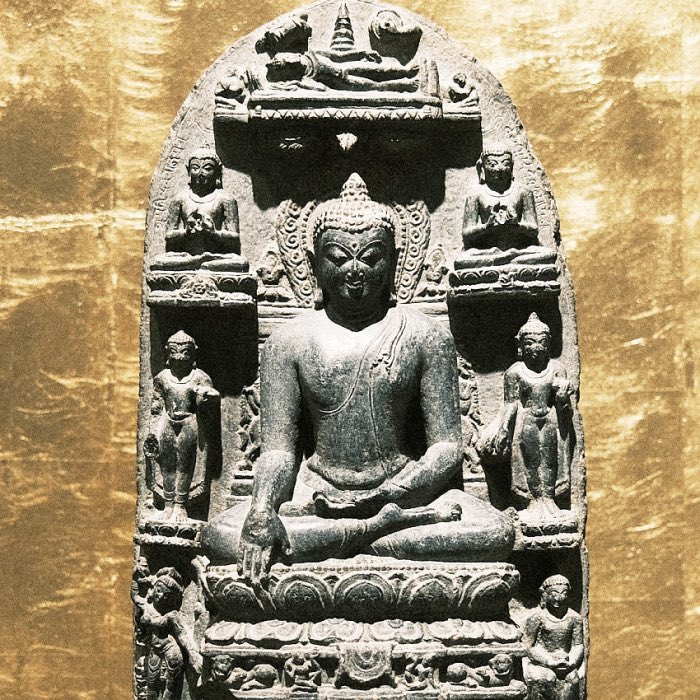

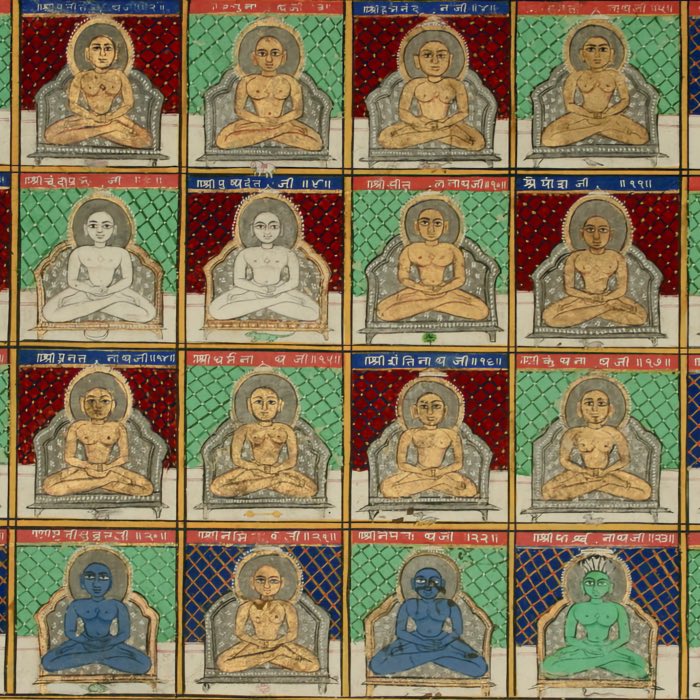

Jainism

Sanskrit also played a role in Jain, particularly in later philosophical and narrative works. While early Jain scriptures were composed in Prakrit, Sanskrit later became a medium for systematizing Jain philosophy and cosmology, as seen in works like the Tattvārtha Sūtra.

Writing systems and their evolution

Sanskrit, known primarily as an oral language in its early history, was eventually transcribed into writing to preserve its extensive corpus of religious, literary, and philosophical texts. The transition from oral to written transmission began during the post-Vedic period and coincided with the development of ancient Indian scripts.

Brāhmī: The foundation

The earliest known script used for Sanskrit texts was the Brāhmī script, which originated around the 3rd century BCE. Brāhmī is considered the precursor to most South and Southeast Asian scripts. It was used for inscriptions and early manuscripts, marking the first efforts to preserve Sanskrit in written form.

Diverse regional scripts

As Sanskrit spread across the Indian subcontinent, it was adapted to various regional scripts, reflecting the cultural and linguistic diversity of ancient India:

- Devanāgarī Script: Today, Devanāgarī is the script most commonly associated with Sanskrit. It emerged around the 7th century CE and became the standard for classical texts in northern India.

- Grantha Script: Used primarily in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the Grantha script was developed to write Sanskrit alongside native Dravidian languages.

- Śāradā Script: Popular in Kashmir and adjacent regions, this script was widely used during the first millennium CE.

- Gupta Script: Prevalent during the Gupta Empire (circa 4th–6th century CE), this script was instrumental in the development of later scripts, including Devanāgarī.

Sanskrit’s adaptability to multiple scripts underscores its role as a pan-Indian lingua franca. While its phonetic precision was preserved through oral recitation, writing expanded its accessibility and longevity.

Conclusion

Sanskrit, as a key member of the Indo-European language family, provides a vital link to understanding linguistic evolution, historical migration, and cultural interconnectedness. Its phonetic precision, grammatical sophistication, and literary richness set it apart as a cornerstone of Indo-European linguistics. Beyond its linguistic significance, Sanskrit played an unparalleled role in shaping the spiritual and intellectual traditions of South Asia and influencing cultures across Central and East Asia through its association with Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain texts. The language’s adoption for philosophical, religious, and literary discourse highlights its adaptability and prestige. By studying Sanskrit, we not only uncover the shared heritage of Indo-European languages but also gain deeper insights into the striking capacity of language to convey and shape human thought and experience.

References and further reading

- Annette Wilke, Oliver Moebus, Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, 2011, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 978-3-11-024003-0

- Macdonell, A. A., A Sanskrit Grammar for Students, 1989, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN: 978-8120805040

- Benjamin W. Fortson IV, Indo-European Language and Culture. An Introduction, 2010, 2nd edition, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1-4051-8896-8

- Monier-Williams, M., A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, 2011, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN: 978-8120831056

- Macdonell, A. A., A History of Sanskrit Literature, 1997, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN: 978-8120800953

- Beekes, R. S. P., Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction, 2011, John Benjamins, ISBN: 978-9027211866

- Geldner, Karl Friedrich, Elementarbuch der Sanskrit-Sprache: Grammatik, Texte, Wörterbuch, 2002, De Gruyter, ISBN: 978-3110175899

- Manfred Mayrhofer, Sanskrit-Grammatik mit sprachvergleichenden Erläuterungen, 1978, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 978-3-11-007177-1

- Ulrich Stiehl, Sanskrit-Kompendium. Ein Lehr-, Übungs- und Nachschlagewerk. Devanagari-Ausgabe, 2007, Hüthig Jehle Rehm, 4th edition, ISBN: 978-3-87081-539-4

- Walter H. Maurer, The Sanskrit Language, 2009, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0-415-49143-3

comments