The Indo-European language family: Linguistic roots of European and South Asian civilizations

The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language, the reconstructed ancestor of the Indo-European language family, is one of the most significant discoveries in historical linguistics. Spoken thousands of years ago, PIE gave rise to languages such as English, Hindi, Greek, and Russian, which are integral to many of today’s cultures and societies. I believe, that studying PIE and its descendants offers insights into patterns of human migration, cultural exchange, and the evolution of language itself.

Language families of the world, Indo-European in yellow. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Language families of the world, Indo-European in yellow. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Origins and reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European

Both, the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) and the Indo-European language family are also known as the Indo-Germanic language family. However, neither term is entirely accurate, as the languages extend far beyond the borders of India and Germany. The term “Indo-European” is now widely used to encompass the full range of languages within the family.

Evidence and reconstruction methods

The concept of PIE stems from observations made by early comparative linguists. Sir William Jones, in 1786, famously noted similarities between Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin, suggesting a common origin. These insights laid the foundation for reconstructing PIE using the comparative method, which identifies systematic correspondences in sounds, grammar, and vocabulary across descendant languages.

For example, words like pater (Latin), πατήρ (patēr, Greek), and pitṛ (Sanskrit) point to the PIE root *pətér* (father). Additionally, PIE’s inflectional morphology suggests a highly synthetic language with complex noun declensions, verb conjugations, and pronouns. PIE also employed ablaut — a system of vowel alternations — to mark grammatical distinctions, as seen in the root *bher-* (carry), appearing as *bheróti* (he carries) and *bhérti* (he carried). As the PIE roots are reconstructed, they are generally marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate their hypothetical nature. Below are some further examples of PIE roots and their reflexes in descendant languages:

| PIE Root | Meaning | Sanskrit | Ancient Greek | Latin | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *wódr̥* | water | áp-ám (gen.) | hydōr (ἑυδωρ) | aqua | water |

| *pətér* | father | pitá́ | patēr | pater | father |

| *dóm-os* | house | dáma | dómos | domus | domestic |

| *treyes* | three | trayas | treis | trēs | three |

| *bher-* | carry/bear | bhárati | phérō | ferre | bear |

Archaeological and genetic evidence

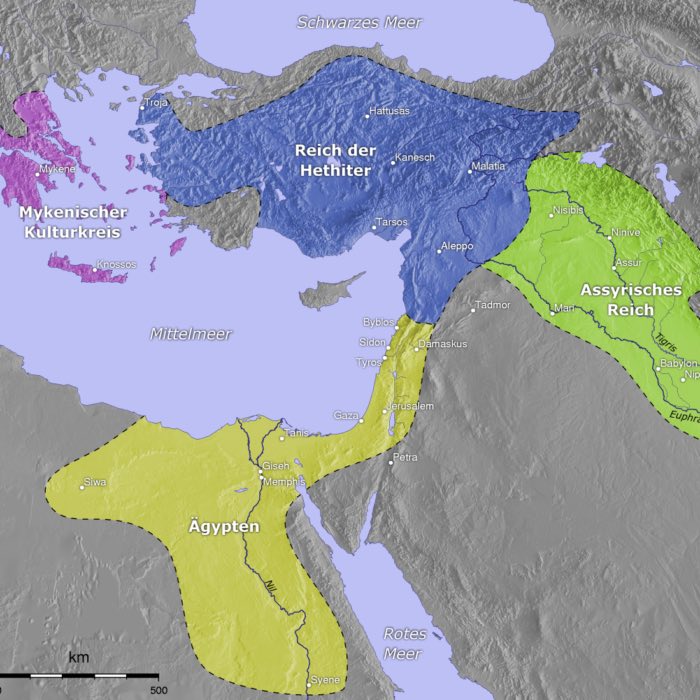

Linguistic findings align with archaeological evidence tracing PIE’s speakers to the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 4000–2500 BCE, as proposed by the Kurgan hypothesis. These early pastoralists likely spread their language through migration, facilitated by innovations like horse domestication and wheeled vehicles. An alternative view, the Anatolian hypothesis, places PIE’s origin in Anatolia (modern Turkey) around 7000–6000 BCE, suggesting agricultural expansion as the primary mechanism for its spread.

Spread and diversification of PIE

As PIE speakers migrated, their language diversified into regional dialects. Contact with other linguistic groups introduced loanwords and structural changes, further accelerating linguistic divergence. Over centuries, these dialects became distinct languages, forming the branches of the Indo-European family.

Indo-European migrations. The animated map gives an overall impression of the migrations of the Indo-European peoples. The map is a simplification; in the details, many things are not exactly right. The first migration into the Danube Valley, for example, did not proceed from the Yamna culture, which started almost a millennium later. But altogether, the idea is to give a general impression of the migrations. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Indo-European migrations. The animated map gives an overall impression of the migrations of the Indo-European peoples. The map is a simplification; in the details, many things are not exactly right. The first migration into the Danube Valley, for example, did not proceed from the Yamna culture, which started almost a millennium later. But altogether, the idea is to give a general impression of the migrations. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Theories of spread

Several theories attempt to explain the spread and diversification of PIE. The Kurgan hypothesis posits a migration from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, while the Anatolian hypothesis associates PIE with early farming practices in Anatolia. These models highlight the complex interplay of cultural, technological, and environmental factors in linguistic evolution. However, they also underscore the challenges of reconstructing ancient migrations and interactions.

Kurgan hypothesis

The Kurgan hypothesis suggests that PIE speakers originated in the Pontic-Caspian steppe (modern Ukraine and southern Russia) around 4000–2500 BCE. These communities were primarily pastoralists who domesticated horses and developed wheeled vehicles. Their technological and social advantages facilitated their migration into Europe and Asia, where they interacted with and often replaced existing populations.

Map of Indo-European migration from around 4000 to 1000 BC (Kurgan hypothesis). The migration to Anatolia could have taken place either via the Caucasus (not shown) or via the Balkans. Pink: original homeland according to the Kurgan hypothesis; blood orange: Indo-European speaking peoples until 2500 BC, orange: colonization around 1000 BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of Indo-European migration from around 4000 to 1000 BC (Kurgan hypothesis). The migration to Anatolia could have taken place either via the Caucasus (not shown) or via the Balkans. Pink: original homeland according to the Kurgan hypothesis; blood orange: Indo-European speaking peoples until 2500 BC, orange: colonization around 1000 BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another map of Indo-European migration according to the Kurgan hypothesis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another map of Indo-European migration according to the Kurgan hypothesis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Anatolian Hypothesis

An alternative view, proposed by Colin Renfrew, posits that PIE emerged in Anatolia (modern Turkey) around 7000–6000 BCE. This hypothesis associates the spread of PIE with the diffusion of early farming practices rather than conquest and migration. While this theory has less linguistic support than the Kurgan hypothesis, it underscores the importance of agriculture in cultural transmission.

Both theories, the Kurgan hypothesis and the Anatolian hypothesis, underscore the interplay of cultural, technological, and environmental factors in linguistic evolution.

Additional theoretical models

Further models have been proposed to explain the diversification of PIE and its daughter languages:

- Family tree model: Proposed by August Schleicher, this model represents the development of PIE and its daughter languages as a branching tree. Each branch signifies a dialect group that evolved into distinct languages over time. While helpful in visualizing relationships, the model simplifies the complex interactions between early dialects.

- Wave theory: Developed by Johannes Schmidt, this theory suggests that linguistic innovations spread like waves from a central point, influencing neighboring dialects. This accounts for overlapping features among languages not strictly on the same branch of the family tree.

- Substrate theory: Hans Krahe and Hermann Hirt proposed that PIE’s diversification was influenced by contact with non-PIE languages. These interactions introduced new features, particularly in vocabulary and syntax, shaping the daughter languages.

- Laryngeal hypothesis: Proposed by Ferdinand de Saussure and later refined, this hypothesis posits the existence of laryngeal consonants in PIE (h₁, h₂, h₃). These sounds left traces in descendant languages, such as vowel coloration in Greek and Sanskrit.

Branches of the Indo-European Language family

The Indo-European family comprises several major branches, each with unique characteristics and historical significance. These branches include:

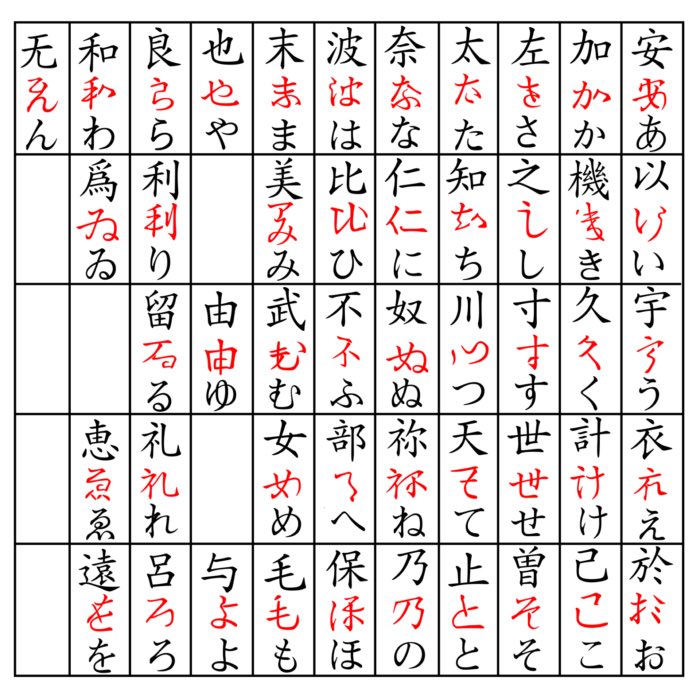

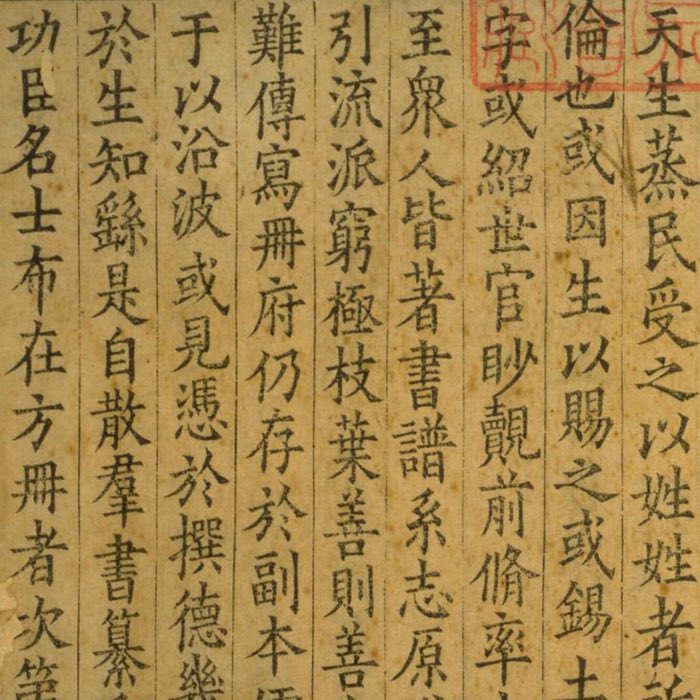

- Indo-Iranian: Sanskrit, Hindi, Persian, and Pashto reflect the easternmost expansion of PIE. Sanskrit, one of the oldest attested Indo-European languages, has deeply influenced South Asian culture.

- Italic: Latin and its Romance descendants, such as Italian, French, and Spanish, were central to European civilization and scholarship.

- Germanic: English, German, and Dutch exhibit unique sound shifts like Grimm’s Law, marking their divergence from other branches.

- Celtic: Once widespread in Western Europe, Celtic languages like Irish and Welsh now survive in limited regions.

- Slavic: Russian, Polish, and Czech dominate Eastern Europe, reflecting a rich literary and cultural tradition.

- Baltic: Lithuanian and Latvian retain archaic features, offering valuable insights into PIE.

- Hellenic: Greek boasts an unbroken literary tradition from the Mycenaean era to modern times.

- Armenian and Albanian: Independent branches with unique linguistic developments.

- Anatolian and Tocharian (Extinct): Early offshoots providing crucial evidence for PIE reconstruction.

Indo-European language family tree based on “Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis of Indo-European languages” by Chang et al. (2015). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Indo-European language family tree based on “Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis of Indo-European languages” by Chang et al. (2015). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Phonology and morphology of PIE

Phonological system

PIE’s reconstructed phonology includes:

- Consonants: Plosives (p, t, k), aspirated plosives (bʰ, dʰ, gʰ), and labiovelars (kʷ, gʷ).

- Ablaut: Vowel alternations (e, o, Ø) that conveyed grammatical distinctions.

- Satem-centum Split: The satem-centum split is a key feature distinguishing early Indo-European branches. Satem languages, like Sanskrit, altered PIE palatovelars to sibilants, while centum languages, such as Latin and Greek, retained velar pronunciations. This distinction highlights early geographic and phonological diversification within the family.

The superscripts in notations such as bʰ and kʷ represent specific phonetic features of PIE consonants, reflecting key articulatory characteristics.

Approximate extent of the centum (blue) and satem (red) areals. The darker red (marking the Sintashta/Abashevo/Srubna archaeological cultures’ range) is the area of the origin of satemization according to von Bradke’s hypothesis, which is not accepted by most linguists. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Approximate extent of the centum (blue) and satem (red) areals. The darker red (marking the Sintashta/Abashevo/Srubna archaeological cultures’ range) is the area of the origin of satemization according to von Bradke’s hypothesis, which is not accepted by most linguists. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Aspirated consonants (ʰ)

Aspirated consonants, marked by ʰ, indicate aspiration – puff of breath accompanying the consonant. These sounds are common in PIE and have evolved differently across its descendant languages. Examples include:

- bʰ: an aspirated voiced bilabial plosive.

- dʰ: an aspirated voiced dental plosive.

Aspirated consonants are preserved in some branches like Sanskrit (bh, dh) but have disappeared or transformed in others (e.g., Greek, Latin).

Labiovelar consonants (ʷ)

Labiovelar consonants, marked by ʷ, signify labialization, where the sound is pronounced with simultaneous lip rounding and velar articulation. Notable examples include:

- kʷ: A voiceless labiovelar plosive.

- gʷ: A voiced labiovelar plosive.

Labiovelars have evolved differently across Indo-European languages:

- In Latin (a centum language), kʷ often appears as “qu” (e.g., kwis → quis).

- In Sanskrit (a satem language), labiovelars simplified into plain velars (e.g., kʷis → kas).

Morphological complexity

PIE was a highly inflectional language. Nouns were marked for cases like nominative and genitive, while verbs distinguished tense, aspect, and mood. The derivational morphology enabled word formation through prefixes and suffixes, as seen in the PIE root *ped-* (foot), which evolved into Latin pes and Sanskrit pāda.

Cultural and historical impact

The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language laid the foundation for the linguistic and cultural frameworks of many influential civilizations. As PIE diversified, it gave rise to linguistic branches such as Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Old Persian, which became integral to the societies that used them.

Sanskrit, with its origins in South Asia, preserved and disseminated ancient Indian spiritual and philosophical traditions through foundational texts like the Rigveda and the Mahabharata. These texts continue to shape the cultural and religious practices of the region. Greek, on the other hand, enabled the articulation of philosophical, scientific, and artistic ideas that became the cornerstone of Western intellectual tradition, with figures such as Plato and Aristotle leading the way. Latin served as the lingua franca of the Roman Empire, facilitating advancements in law, governance, and science, while also influencing the evolution of the Romance languages spoken by millions today.

The interconnectedness of these languages and their societies reflects the deep historical ties within the Indo-European family. By tracing their shared linguistic roots, we uncover a history of migration, cultural exchange, and intellectual development that has profoundly shaped modern civilizations. The enduring legacy of PIE serves as a reminder of the lasting influence of language in shaping and advancing human civilizations.

References and further reading

- Hans J.J.G. Holm, Die ältesten Räder der Welt – von den Indogermanen erfunden oder nur bei ihrer Ausbreitung benutzt? Neueste archäologische und sprachwissenschaftliche Ergebnisse, 2024, Inspiration Unlimited, ISBN: 978-3-94512754-4

- Wolfram Euler, Die Rolle von Etymologie und Grammatik in Sprachentwicklung und Sprachverwandtschaft – Gesetzmäßigkeiten und Regeln, 2012, In: Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, Band 17, S. 25–66, PDFꜛ

- Benjamin W. Fortson IV, Indo-European Language and Culture. An Introduction, 2010, 2nd edition, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1-4051-8896-8

- Matthias Fritz, Michael Meier-Brügger, Indogermanische Sprachwissenschaft, 2021, De Gruyter, 10th edition, ISBN: 978-3-11-059832-2

- Oswald Szemerényi, Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft, 1990, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 4th edition, ISBN: 3-534-04216-6

- Eva Tichy, Indogermanistisches Grundwissen, 2000, Hempen,ISBN: 3-934106-14-5

- Mallory, J. P., & Adams, D. Q., Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, 1997, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1884964985

- Anthony, D. W., The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, 2007, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691148182

- Beekes, R. S. P., Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction, 2011, John Benjamins, ISBN: 978-9027211866

- Chang, Will, Chundra, Cathcart, Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis, 2015, Language. 91 (1): 194–244. doi: 10.1353/lan.2015.0005ꜛ, PDFꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Proto-Indo-European languageꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Indo-European languagesꜛ

- Wikiwand article on Centum and satem languagesꜛ

comments