Book printing before Gutenberg: The Asian roots of printing technology

The history of book printing is a fascinating journey that spans across continents and centuries. Long before Johannes Gutenberg’s famous introduction of the printing press in Europe, significant advancements in printing technology had already taken place in Asia. The Chinese and Koreans were pioneers in developing various printing methods, including woodblock printing and movable type, long before Gutenberg’s later innovations. And although Gutenberg is considered revolutionary in the European context, I believe he can be seen more accurately as an improver and developer of existing technologies. In May this year, I had the opportunity to visit the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, which inspired this brief outline of the history of letterpress printing. All photos shown here were taken by me during my visit to the Museum.

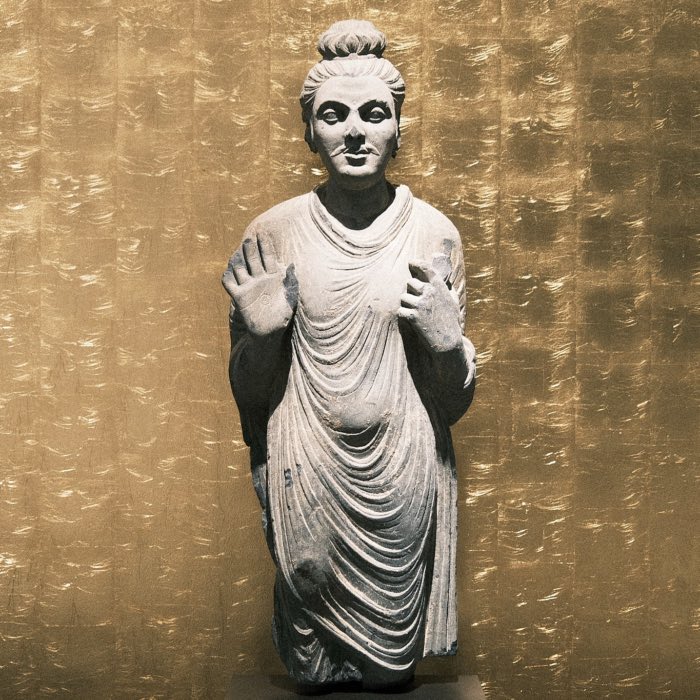

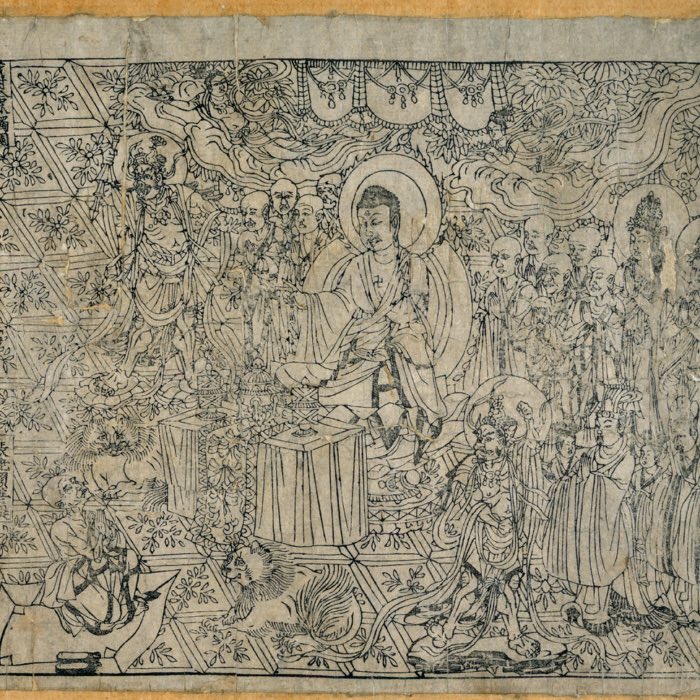

One of the oldest printed books in the world: a copy of the Diamond Sutra handscroll, dated 868 and found in one of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein. The text (see also Buddhist caves) is a Mahayana Buddhist sutra from the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras or ‘Perfection of Wisdom’ sutras, and emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment.

One of the oldest printed books in the world: a copy of the Diamond Sutra handscroll, dated 868 and found in one of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein. The text (see also Buddhist caves) is a Mahayana Buddhist sutra from the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras or ‘Perfection of Wisdom’ sutras, and emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment.

Ancient printing technologies

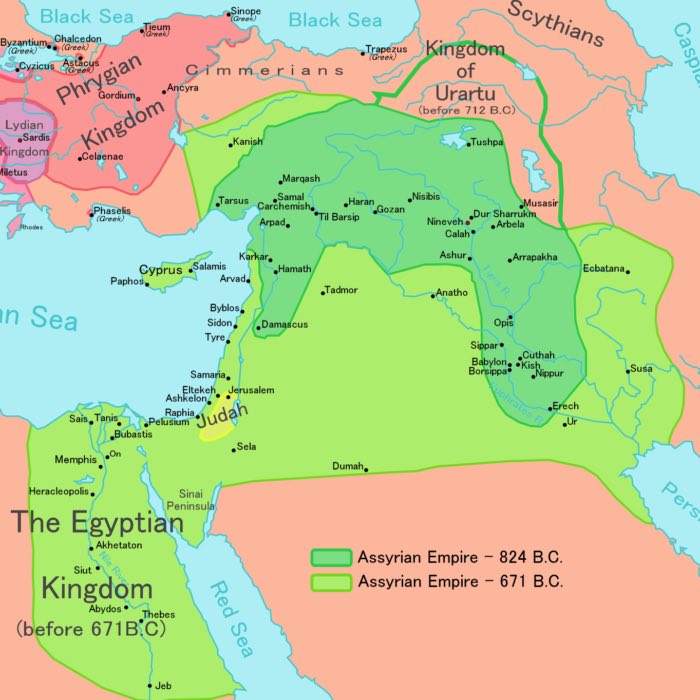

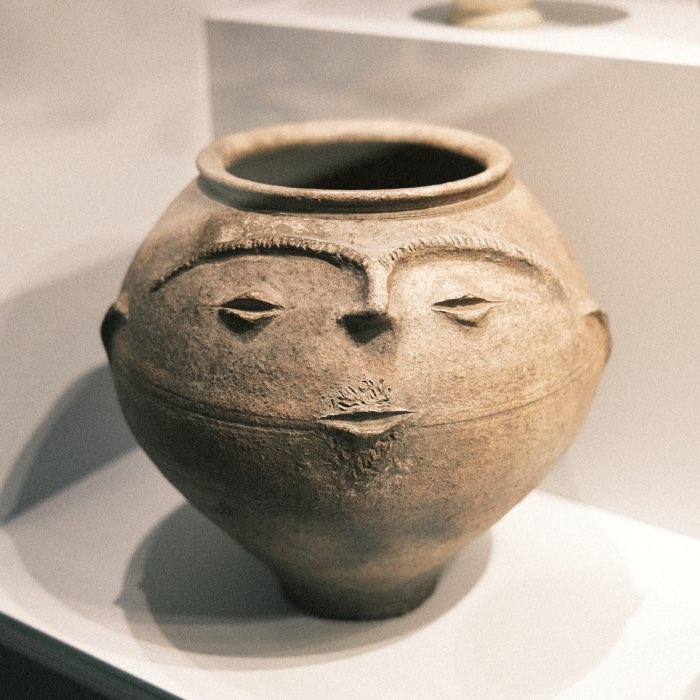

If we think of printing as the reproduction of text or images, the history of printing can be dated back to ancient times. Various civilizations developed methods to reproduce written information, such as the use of stamps, seals, and engraved tablets. For instance, in the tombs of Thebes and Babylon, bricks with inscribed texts have been found. The Assyrians created chronicles using burnt clay cylinders covered with characters made from engraved molds. In Athens, maps were engraved onto thin copper plates. Roman potters stamped their pottery with the names of buyers or the intended use of the items. And wealthy Romans gave their children alphabets made from ivory or metal to help them learn to read.

However, all these methods were limited in their ability to reproduce texts on a large scale. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, papyrus from Egypt became scarce in Europe and no other substitute was found except for expensive parchment. In China, the situation was different as we will see in the next section.

Chinese innovations in book printing

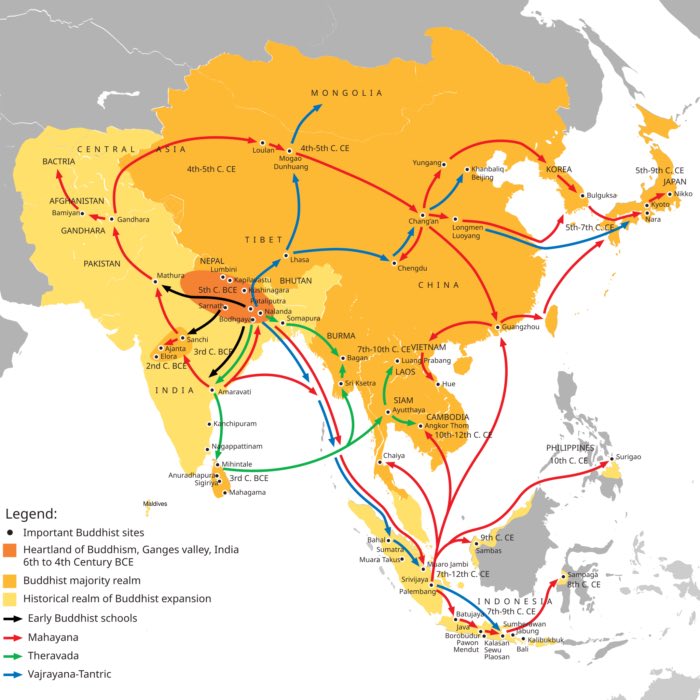

The origins of book printing in China can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). The Chinese developed woodblock printing, a method where text and images were carved into wooden blocks, inked, and pressed onto paper. This method allowed for the reproduction of texts and was primarily used for religious and official documents.

One of the earliest examples of woodblock printing is the “Diamond Sutra”, a Buddhist text printed in 868 CE. The sutra was found in one of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, China, by the archaeologist Aurel Stein in 1907 and is considered one of the oldest surviving printed books in the world. The Diamond Sutra exemplifies the early use of woodblock printing in China and showcases the sophisticated craftsmanship of Chinese woodblock printing that already existed at that time.

The next significant advancement in Chinese printing came with the invention of movable type by Bi Sheng around 1040 CE during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). Bi Sheng’s movable type was made from clay and later from wood, which allowed for individual characters to be rearranged and reused. This innovation marked a departure from the labor-intensive woodblock printing, offering greater flexibility and efficiency. However, the widespread adoption of movable type in China was limited by the complexity of the Chinese script, which required thousands of characters.

Script on bone, oracle bone script on bone and tortoise shell, Anyang, Henan Province (replica, gift of the China Printing Museum, Beijing). Before making important decisions, Chinese rulers consulted their ancestors: cattle shoulder blade bones and tortoise shells were placed in the fire. The cracks caused by the heat were read as an omen of things to come. After the ritual, the day and reason for the questioning as well as the answer were carved on the bones. The signs used for this are called called ‘oracle bone writing’ today.

Script on bone, oracle bone script on bone and tortoise shell, Anyang, Henan Province (replica, gift of the China Printing Museum, Beijing). Before making important decisions, Chinese rulers consulted their ancestors: cattle shoulder blade bones and tortoise shells were placed in the fire. The cracks caused by the heat were read as an omen of things to come. After the ritual, the day and reason for the questioning as well as the answer were carved on the bones. The signs used for this are called called ‘oracle bone writing’ today.

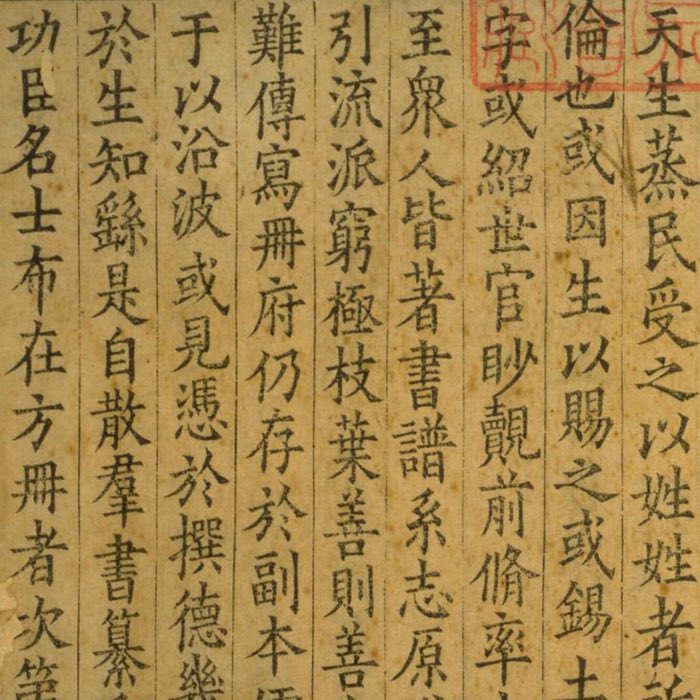

Jinchaeng, Poems and essays by Jong Jo handwritten in Chinese script, from the Korean colleciton. With the introduction of paper in the 3rd/4th century, a manuscript culture emerged in East Asia that continued to exist alongside the art of printing and is still practiced today. The educated classes, which essentially included the officials of the state bureaucracies, practiced calligraphy as a form of contemplation, copied and collected books and wrote commentaries on classical texts, as well as poems, stories and non-fiction.

Jinchaeng, Poems and essays by Jong Jo handwritten in Chinese script, from the Korean colleciton. With the introduction of paper in the 3rd/4th century, a manuscript culture emerged in East Asia that continued to exist alongside the art of printing and is still practiced today. The educated classes, which essentially included the officials of the state bureaucracies, practiced calligraphy as a form of contemplation, copied and collected books and wrote commentaries on classical texts, as well as poems, stories and non-fiction.

‘The four treasures of the scholar’s room’ - ink, rubbing stone, brush and paper were part of the basic equipment of artists, scholars and civil servants. The black Chinese writing ink is made from spruce soot, animal glue and musk and camphor additives. The mixed paste is dried in moulds and stored as an ink stick. This stick is rubbed in a stone mould and water is gradually dripped into it until a solution suitable for writing is obtained. The round, pointed brush made of animal hair writes thinly with the tip or vigorously with the body of the hair, depending on the pressure. Using it requires physical control and is also a meditative exercise.

‘The four treasures of the scholar’s room’ - ink, rubbing stone, brush and paper were part of the basic equipment of artists, scholars and civil servants. The black Chinese writing ink is made from spruce soot, animal glue and musk and camphor additives. The mixed paste is dried in moulds and stored as an ink stick. This stick is rubbed in a stone mould and water is gradually dripped into it until a solution suitable for writing is obtained. The round, pointed brush made of animal hair writes thinly with the tip or vigorously with the body of the hair, depending on the pressure. Using it requires physical control and is also a meditative exercise.

Sutra scroll, rubbing print (reproduction; gift of the China Printing Museum, Beijing).

Sutra scroll, rubbing print (reproduction; gift of the China Printing Museum, Beijing).

Hand-colored woodblock print scroll, depiction of a Medicine Buddha, 990-1070, (reproduction; China Printing Museum, Beijing). The Liao (907-1234), a northern neighbouring dynasty of the Song, began to color woodblock prints by hand.

Hand-colored woodblock print scroll, depiction of a Medicine Buddha, 990-1070, (reproduction; China Printing Museum, Beijing). The Liao (907-1234), a northern neighbouring dynasty of the Song, began to color woodblock prints by hand.

Happiness spreads everywhere, Buddhist text from one of the earliest woodblock prints, 12th cent. (reproduction).

Happiness spreads everywhere, Buddhist text from one of the earliest woodblock prints, 12th cent. (reproduction).

Kai Bao Tripitaka, scroll, collection of Buddhist sutras, printed between 971 and 983 (replica). Tripitaka (Sanskrit) means ‘three-basket’ and refers to the oldest Buddhist canon. This scroll book is only a small part of the first printed collection of sutras in ancient China. For it, 130,000 printing plates were cut, which took 12 years to produce.

Kai Bao Tripitaka, scroll, collection of Buddhist sutras, printed between 971 and 983 (replica). Tripitaka (Sanskrit) means ‘three-basket’ and refers to the oldest Buddhist canon. This scroll book is only a small part of the first printed collection of sutras in ancient China. For it, 130,000 printing plates were cut, which took 12 years to produce.

Printing with wood type. The first works printed with wooden letters were found in 1993 in a pagoda in Ningxia. They were written in the Xi-Xia script. The Xi-Xia dynasty was an empire of the Tanguts in north-west China, founded in 1038 and conquered by the Mongols in 1227.

Printing with wood type. The first works printed with wooden letters were found in 1993 in a pagoda in Ningxia. They were written in the Xi-Xia script. The Xi-Xia dynasty was an empire of the Tanguts in north-west China, founded in 1038 and conquered by the Mongols in 1227.

Adhesive set on copper plate, wooden letters glued in with wax, 1773.

Adhesive set on copper plate, wooden letters glued in with wax, 1773.

Tianjin Clay Figure Zhang Workshop 2009, printing with clay types. Model with scenes from a printing workshop of the Song Dynasty (10-13th century)

Tianjin Clay Figure Zhang Workshop 2009, printing with clay types. Model with scenes from a printing workshop of the Song Dynasty (10-13th century)

Tianjin Clay Figure Zhang Workshop 2009, printing with clay types. Model with scenes from a printing workshop of the Song Dynasty (10-13th century)

Tianjin Clay Figure Zhang Workshop 2009, printing with clay types. Model with scenes from a printing workshop of the Song Dynasty (10-13th century)

Round table with wooden stamp letters. Tables of this kind were used to sort the thousands of characters required for printing with movable type and played a crucial role in the efficiency and organization of the printing process. The round shape of the table allowed for easy rotation, enabling printers to quickly access different sections without moving around the workspace. The surface of the table was divided into multiple compartments or small boxes, each holding a specific set of characters. This segmentation helped in organizing the characters systematically.

Round table with wooden stamp letters. Tables of this kind were used to sort the thousands of characters required for printing with movable type and played a crucial role in the efficiency and organization of the printing process. The round shape of the table allowed for easy rotation, enabling printers to quickly access different sections without moving around the workspace. The surface of the table was divided into multiple compartments or small boxes, each holding a specific set of characters. This segmentation helped in organizing the characters systematically.

Detail of a round table with wooden stamp letters.

Detail of a round table with wooden stamp letters.

Korean contributions to printing technology

Wood block printing was also prevalent in Korea, where it was used for religious texts, government documents, and literature as well. The oldest Korean block prints are Buddhist spells, so-called Dharani from a pagoda of the Bulguksa temple in Gyeongju from the first half of the 8th century. The Tripitaka Koreana, also called Eighty Thousand Tripitaka (八萬大藏經), a Buddhist canon created in Goryeo, which was printed in 6000 volumes with over 80,000 wooden printing blocks, is also considered a huge cultural achievement. The production of the entire wooden printing blocks took 16 years (1236-1251). All the printing blocks are still preserved in a well-ventilated historical building of Haeinsa Monastery in very good condition.

In the early 13th century, Korea made a significant leap in printing technology with the development of metal movable type. The Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392 CE) improved upon Chinese techniques by creating durable metal type, which was more precise and long-lasting than clay or wood. The oldest known book printed with metal movable type is the Jikji simgyeong (直指心經), an anthology of the Zen teachings of great Buddhist priests printed in 1377 CE, predating Gutenberg’s Bible by nearly 80 years. Another reference to metal type printing in Korea is the book Goryeosa (高麗史; History of Goryeo) from 1392, in which King Gongyang (恭讓) granted the “Seojeokwon” (書籍院), the book and publication center, responsibility and supervision for all matters related to the use of metal type and book printing. The Korean innovation of metal movable type played a crucial role in the efficiency and quality of printed materials.

Printing block in Hangul, songs about the ‘Reflection of the moon in 1000 rivers’ (reproduction).

Printing block in Hangul, songs about the ‘Reflection of the moon in 1000 rivers’ (reproduction).

Korean letter cabinet (replica) with metal letters, tweezers, sticks, and printing form.

Korean letter cabinet (replica) with metal letters, tweezers, sticks, and printing form.

Printing moulds for the arches of the Jikji, the oldest book printed with metal type, Heung-deok-sa Temple, Cheong-Ju, 1377 (replica).

Printing moulds for the arches of the Jikji, the oldest book printed with metal type, Heung-deok-sa Temple, Cheong-Ju, 1377 (replica).

Printing moulds for the arches of the Jikji, the oldest book printed with metal type, Heung-deok-sa Temple, Cheong-Ju, 1377 (replica).

Printing moulds for the arches of the Jikji, the oldest book printed with metal type, Heung-deok-sa Temple, Cheong-Ju, 1377 (replica).

Model of a Korean friction printing workshop.

Model of a Korean friction printing workshop.

Model of a Korean friction printing workshop.

Model of a Korean friction printing workshop.

Japanese adaptations

The oldest surviving prints in Japan were produced on behalf of Shōtoku-tennō (764-770) using copper or wooden blocks. He is said to have had a million paper rolls inserted into small wooden pagodas printed, which is why they were also called million-pagoda dharani, hyakumantō darani. These were distributed to ten Japanese monasteries.

Knowledge of letterpress printing came to Japan in two ways. After trade with Portugal began in 1549, Portuguese missionaries brought a European printing press to the country to produce the books needed to spread the Christian faith. Books were printed using both Japanese and European type.

During expeditions to Korea in the 1590s, Korean printing technique with ceramic and bronze letters, called, called Chōsen kokatsujiban (朝鮮古活字版), was learned and a complete printing press was brought to Japan to be donated to the emperor. The acquired knowledge was used to set up their own printing workshops in Japan. Letters as well as printed works were commissioned by the government, but also by temples and merchants. All kinds of literature were printed - Chinese and Japanese classics as well as historical, medical and religious texts. They were also distributed commercially.

In the wake of the ban on Christianity in 1638 and the subsequent ‘Land Closure’ law (Japanese: sakoku, 鎖国), which sealed Japan off from the remnants of the world for over 200 years until 1854 and banned the import of foreign books, the Japanese returned to traditional printing with wooden boards.

Classical Japanese tale Homotsushu, print with wood type, 1609, Japan. Early letterpress printing in the 16th/17th century.

Classical Japanese tale Homotsushu, print with wood type, 1609, Japan. Early letterpress printing in the 16th/17th century.

Japanese Lotus Sutra, woodblock print on blue-colored paper with water lily and gold stripe decoration, late 18th or early 19th century, Japan.

Japanese Lotus Sutra, woodblock print on blue-colored paper with water lily and gold stripe decoration, late 18th or early 19th century, Japan.

Gutenberg and the European printing revolution

While movable type and printing technology had been developed in Asia centuries earlier, Johannes Gutenberg’s contributions in the mid-15th century were pivotal for Europe. Gutenberg adapted movable metal type for use in Europe, but his key innovation was the integration of the printing press. Modeled after the screw presses used in wine production, Gutenberg’s press allowed for uniform pressure to be applied to the printing surface, resulting in clear and consistent prints.

Gutenberg’s printing press revolutionized the production of books by making it possible to print large quantities quickly and at a lower cost. This efficiency facilitated the mass production of texts, which in turn made books more accessible to a wider audience. The Gutenberg Bible, printed in the 1450s, exemplified the high quality and replicability of this new technology.

Gutenberg’s improvements had profound cultural and intellectual impacts. The rapid spread of printed materials facilitated the dissemination of knowledge, ideas, and literacy. This played a crucial role in the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution. The ability to produce and distribute books widely transformed European society, leading to greater access to education and information.

Officium Beatac Mariae Virginis, book of hours, Antwerpen, 1575. Decorative borders made with metallic copper, engraved picture bordure.

Officium Beatac Mariae Virginis, book of hours, Antwerpen, 1575. Decorative borders made with metallic copper, engraved picture bordure.

Christ at the cross (no further description identifiable).

Christ at the cross (no further description identifiable).

Passio Christi, The suffering of Christ, Straßburg, Johann Knoblouch d. Ä., 1506. In the black-and-white print, the illustrator Urs Graf (1455- 1528) applied finely tuned batching to create shades of gray and plasticity.

Passio Christi, The suffering of Christ, Straßburg, Johann Knoblouch d. Ä., 1506. In the black-and-white print, the illustrator Urs Graf (1455- 1528) applied finely tuned batching to create shades of gray and plasticity.

Psalterium Benedictinum, the 150 biblical psalm texts for the Order of Saint Benedict (second, altered edition of the 1457 Mainzer Psalter), Mainz, Johannes Fust and Peter Schöffer, 1459. Print with four colors and two different font sizes on parchment. The musical notes were entered by hand.

Psalterium Benedictinum, the 150 biblical psalm texts for the Order of Saint Benedict (second, altered edition of the 1457 Mainzer Psalter), Mainz, Johannes Fust and Peter Schöffer, 1459. Print with four colors and two different font sizes on parchment. The musical notes were entered by hand.

Sectional two-color metal cut initials, reconstructed based on the Mainzer Psalter. Sectional, red and blue dyed metalout letters allowed the printing of the traditional Fleuronnée initials. However, multi-color initials were elaborate and expensive.

Sectional two-color metal cut initials, reconstructed based on the Mainzer Psalter. Sectional, red and blue dyed metalout letters allowed the printing of the traditional Fleuronnée initials. However, multi-color initials were elaborate and expensive.

Laien-Spiegel, introduction to academic law, Straßburg, Matthias Hupfuff, 1510.

Laien-Spiegel, introduction to academic law, Straßburg, Matthias Hupfuff, 1510.

Totentanz, allegorical presentation of the power of death based on the woodcuts by Holbein, Augsburg, Jost de Necker, 1544.

Totentanz, allegorical presentation of the power of death based on the woodcuts by Holbein, Augsburg, Jost de Necker, 1544.

Collection of miniature books.

Collection of miniature books.

Collection of miniature books.

Collection of miniature books.

Bertrand-Quinquet, Traité de l’Imprimerie Paria, An VII, 1799, first edition of this French printer’s handbook, which was dedicated to the printer Pierre Didot. It contains a history of the development of typography in the 18th century.

Bertrand-Quinquet, Traité de l’Imprimerie Paria, An VII, 1799, first edition of this French printer’s handbook, which was dedicated to the printer Pierre Didot. It contains a history of the development of typography in the 18th century.

Replica of a copper intaglio printing press after Gilles Demarteau (1722-1776).

Replica of a copper intaglio printing press after Gilles Demarteau (1722-1776).

High-speed printing press from Maschinenfabrik Klein & Forst Geisenheim/Rhein (built in 1848).

High-speed printing press from Maschinenfabrik Klein & Forst Geisenheim/Rhein (built in 1848).

Color pigments for the production of paints.

Color pigments for the production of paints.

Critical view on Gutenberg’s role

While Gutenberg is often hailed as the “inventor” of printing in the Western world, it is more accurate to view him as an improver and developer of pre-existing technologies. His innovations built on the foundations that already existed in Europe. Several examples of knowledge of the typographical principle are known from the Middle Ages, such as the Prüfeningen consecration inscription in Regensburg, which was created in 1119 using the stamp technique. In the cathedral of Cividale in northern Italy there is a silver altarpiece of the Patriarch Pilgrim II (1195-1204), whose Latin inscription was produced with the help of letter punches. This technique can also be found between the 10th and 12th centuries in in the Byzantine cultural area, with which the Venetian Maritime Republic maintained close trade relations. In Chertsey Abbey in England in the 13th century, the remains of a pavement of letter tiles were laid according to the Scrabble principle. The technique is also documented for Zinna Abbey near Berlin and Aduard Abbey in the Netherlands.

Gutenberg enhanced and adapted these technologies to meet the needs of the emerging society starving for knowledge at the onset of the Renaissance era. By perfecting the use of metal movable type and integrating it with a mechanical press, Gutenberg created a system that significantly advanced the efficiency and quality of book production.

Conclusion

Exchanging and transmitting information and knowledge is most likely one of humanity’s most important achievements and a key to its success. The development of printing technologies has played a crucial role in this process. The history of book printing before Gutenberg is rich and dates back to ancient times, spreading across Asia and Europe. The Chinese and Koreans were pioneers in developing various printing methods, including woodblock printing and movable type, long before Gutenberg’s later innovations. While Gutenberg’s contributions were transformative for Europe, it is essential to recognize and acknowledge the long history of printing technologies that preceded him.

These early advancements in printing were pivotal in enabling the widespread dissemination of information, reflecting the timeless human desire and need to share knowledge. This foundation laid the groundwork for the Information Age. The ability to mass-produce texts allowed for the rapid spread of knowledge, ideas, and literacy, which are fundamental to the digital era we live in today. The principles of efficient information replication and distribution established by early printing technologies continue to underpin the mechanisms of the internet and digital communication. This illustrates the enduring legacy of these innovations in shaping the continuous evolution of global information exchange, driven by humanity’s unchanging quest for knowledge.

References and further reading

- Lucille Chia, Hilde de Weerdt, Knowledge and text production in an age of print: China, 900-1400, 2011, BRILL, ISBN: 9789004192287

- Joseph P. McDermott, A social history of the Chinese book – Books and literati culture in late imperial China, 2006, Hong Kong University Press, ISBN: 9789622097810

- Tsuen-hsuin Tsien, Written On Bamboo & Silk - The Beginnings Of Chinese Books & Inscriptions, 2004, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 9780226814186

- Jixing Pan, On the Origin of Printing in the Light of New Archaeological Discoveries, In: Chinese Science Bulletin, Vol 42, Nr. 12, 1997, S. 976–981, S. 979 f.

- Alfons Dufey, Schrift u. Druck in Ostasien, In: Das Buch im Orient, Wiesbaden 1982. S. 297.

- Douglas C. McMurtrie, The Book: The Story of Printing & Bookmaking, 1962, Oxford University Press, seventh edition

comments