A brief history of writing

I believe, that writing is one of the most significant inventions in human history, playing a crucial role in the development and success of civilizations. From ancient pictographs to modern alphabets, writing has enabled the recording and dissemination of knowledge, fostering communication, culture, and governance. In this article, we therefore briefly explore the history of writing, tracing its origins in various ancient civilizations and highlighting its profound impact on human progress.

The Rosetta Stone (replica, detail). Gutenberg Museum, Mainz. This stone enabled the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs in the 19th century, as it contained the same text in three scripts: hieroglyphs, demotic, and Greek.

The Rosetta Stone (replica, detail). Gutenberg Museum, Mainz. This stone enabled the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs in the 19th century, as it contained the same text in three scripts: hieroglyphs, demotic, and Greek.

Writing: Its origins and evolution

Writing emerged independently in several regions of the world, each responding to specific societal needs. The earliest writing systems were not primarily tools for artistic expression but practical technologies designed to address administrative and communicative challenges in complex societies. In the following, we briefly touch upon the origins and evolution of writing in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, the Indus Valley, the Americas, and the Mediterranean world.

Mesopotamia: Cuneiform writing

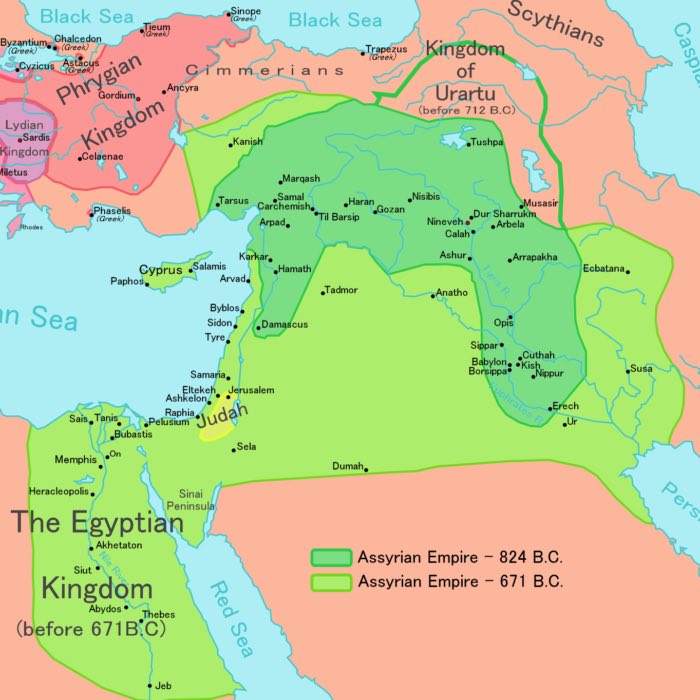

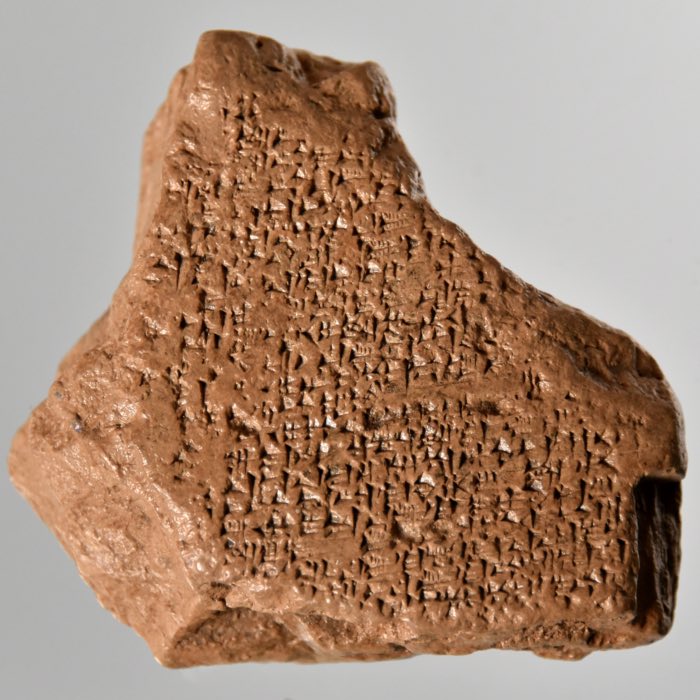

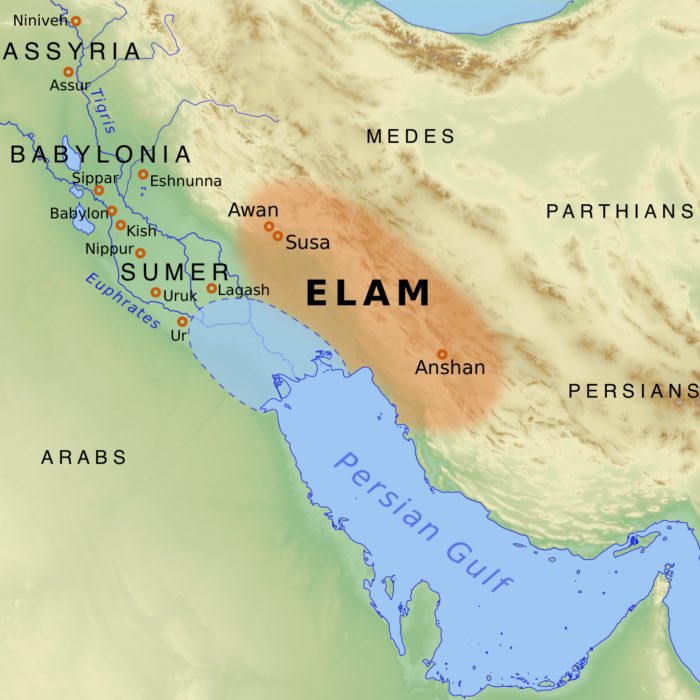

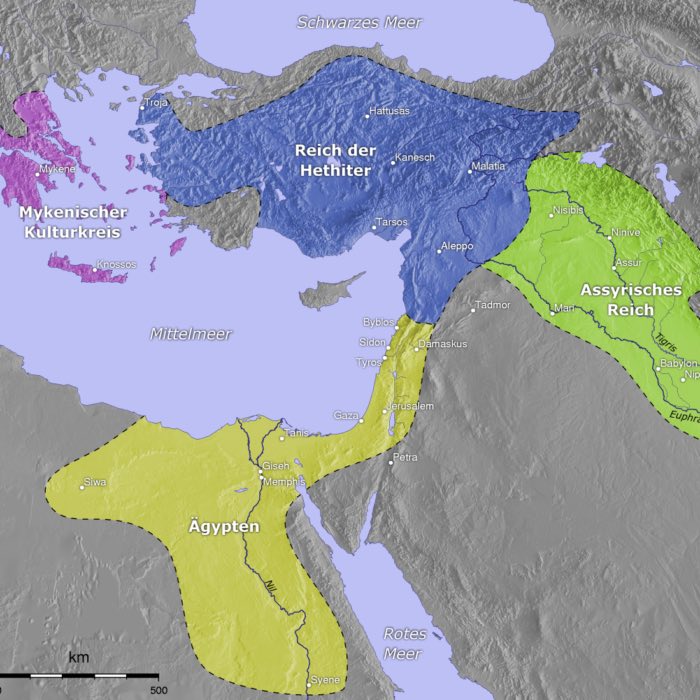

The earliest known writing system, cuneiform, originated in Mesopotamia around 3300 BCE. It evolved as a means of recording economic transactions and inventories in the burgeoning city-states of Sumer. Initially, cuneiform consisted of pictographs – simple drawings representing objects or quantities – inscribed on clay tablets. Over time, these pictographs became increasingly abstract, evolving into a system of wedge-shaped signs pressed into clay with a stylus.

The Kish tablet, bearing what is possibly the earliest known writing – Sumer (c. 3500 BC), from the Ashmolean Museum. Limestone tablet, contains pictographs of heads, feet, hands, numbers and threshing-boards. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Kish tablet, bearing what is possibly the earliest known writing – Sumer (c. 3500 BC), from the Ashmolean Museum. Limestone tablet, contains pictographs of heads, feet, hands, numbers and threshing-boards. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Population centres of Sumer in southern Mesopotamia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Right: Tablet with proto-cuneiform pictographs – Uruk III (late 4th millennium BC). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Cuneiform’s development illustrates the interplay between societal complexity and the need for record-keeping. As trade expanded and governance grew more intricate, written records became indispensable for managing resources, codifying laws, and maintaining political authority. It enabled the Sumerians also to create the first known works of literature, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, and to record scientific knowledge, including astronomical observations and mathematical calculations.

Egypt: Hieroglyphs

Roughly contemporaneous with cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs emerged as a system of pictorial symbols around 3200 BCE. While also initially focused on administrative functions, hieroglyphs quickly acquired religious and ceremonial significance, used to inscribe monumental texts on temples and tombs. Hieroglyphics were carved into stone or written on papyrus, a paper-like material made from reeds. This writing system played a crucial role in the administration of the pharaohs’ vast empires, the documentation of religious texts, and the preservation of cultural heritage through monumental inscriptions such as those found in the pyramids and temples. However, as the use of hieroglyphs declined over centuries and gave way to simpler scripts like Demotic and later Greek, their meaning became obscure and unreadable.

Stela of Sesostris III (replica), plaster cast; original: brown quarzite, from Semna (Nubia, now Sudan), Middle Kingdom, 12th dynasty, ca. 1855 BC, Original in Berlin, Ägypt. Museum. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Stela of Sesostris III (replica), plaster cast; original: brown quarzite, from Semna (Nubia, now Sudan), Middle Kingdom, 12th dynasty, ca. 1855 BC, Original in Berlin, Ägypt. Museum. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

The deciphering of hieroglyphs was only made possible by the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799. This artifact, inscribed with the same text in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Greek, provided the crucial key for linguists to unlock the ancient script. Jean-François Champollion’s systematic comparison of these scripts in the 1820s led to the eventual understanding of hieroglyphic writing, restoring insights into Egypt’s rich historical and cultural legacy. Today, “Rosetta” has become universally synonymous with a key to understanding complex systems and deciphering the unknown.

Stele with Egyptian hieroglyphics. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Stele with Egyptian hieroglyphics. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Representation of the scribe Dersenedi from Memphis, Egypt (Lower Egypt), 5th dynasty (2479-2322 BC), plaster cast, original in Berlin Ägypt. Museum and from red granite. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Representation of the scribe Dersenedi from Memphis, Egypt (Lower Egypt), 5th dynasty (2479-2322 BC), plaster cast, original in Berlin Ägypt. Museum and from red granite. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

The Rosetta Stone (replica), plaster cast; original: granite from Rosetta (Lower Egypt), Ptolemaic period, probably Ptolemy V Epiphanes 196 BC, original in London, British Museum. The Rosetta stone was discovered in 1799 by a French officer near Rosetta (today’s Rashid) in the Nile valley. The black basalt stone is carved with an inscription carried out in three scripts. The text, a decree of the council of Egyptian priests, is written in hieroglyphs, in demotic and in Greek. The Rosetta stone enabled Jean-Francois Champollion to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs via the interpretation of the demotic script. The original stone has been located in the British Museum in London since 1802. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

The Rosetta Stone (replica), plaster cast; original: granite from Rosetta (Lower Egypt), Ptolemaic period, probably Ptolemy V Epiphanes 196 BC, original in London, British Museum. The Rosetta stone was discovered in 1799 by a French officer near Rosetta (today’s Rashid) in the Nile valley. The black basalt stone is carved with an inscription carried out in three scripts. The text, a decree of the council of Egyptian priests, is written in hieroglyphs, in demotic and in Greek. The Rosetta stone enabled Jean-Francois Champollion to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs via the interpretation of the demotic script. The original stone has been located in the British Museum in London since 1802. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

The Rosetta Stone (replica, detail). Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

The Rosetta Stone (replica, detail). Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

China: Oracle bone script and the evolution of chinese script

In ancient China, writing developed somewhat later, with the earliest evidence dating to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). This writing, known as oracle bone script, was deeply tied to religious and divinatory practices. Diviners would inscribe questions addressed to the gods or ancestors on animal bones or turtle shells. These items were then heated until cracks formed, which were interpreted as divine responses. The inscriptions recorded both the questions and, occasionally, the interpreted answers, creating a tangible link between the spiritual and administrative realms.

Diagram comparing the abstraction of pictographs in cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Chinese characters – from an 1870 publication by French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

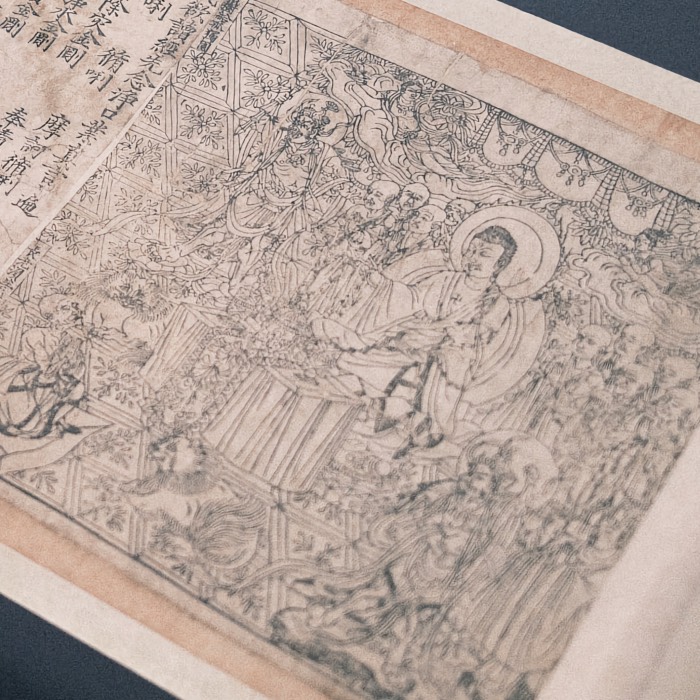

Script on bone, oracle bone script on bone and tortoise shell, Anyang, Henan Province (replica, gifts of the China Printing Museum, Beijing). Before making important decisions, Chinese rulers consulted their ancestors: cattle shoulder blade bones and tortoise shells were placed in the fire. The cracks caused by the heat were read as an omen of things to come. After the ritual, the day and reason for the questioning as well as the answer were carved on the bones. The signs used for this are called called ‘oracle bone writing’ today. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Script on bone, oracle bone script on bone and tortoise shell, Anyang, Henan Province (replica, gifts of the China Printing Museum, Beijing). Before making important decisions, Chinese rulers consulted their ancestors: cattle shoulder blade bones and tortoise shells were placed in the fire. The cracks caused by the heat were read as an omen of things to come. After the ritual, the day and reason for the questioning as well as the answer were carved on the bones. The signs used for this are called called ‘oracle bone writing’ today. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Over time, this early logographic script evolved into more standardized and complex forms, such as the seal script, clerical script, and regular script. These adaptations reflected the growing bureaucratic and cultural needs of Chinese society. Chinese writing played a crucial role in facilitating the centralized administration of vast territories, enabling the compilation of extensive historical records, and promoting the spread of influential philosophical traditions like Confucianism and Daoism. The development of Chinese characters also laid the foundation for one of the longest continuously used writing systems in the world, influencing neighboring cultures such as Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

Left: Locations of the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC) marked in violet, with Shang capitals in marked by red dots. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Right: ‘Shang’ in oracle bone script (top left), bronze script (top right), seal script (bottom left), and regular script (bottom right) forms. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Script written on bamboo sticks with brush and ink, Chu Empire, 7th-3rd century BC (replica). Scroll books made from bamboo sticks: Because there is only limited space for characters on individual sticks, many of them were bound together with silk or leather string to form a scroll book. The custom of writing in columns from top to bottom and from right to left stems from this arrangement. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Script written on bamboo sticks with brush and ink, Chu Empire, 7th-3rd century BC (replica). Scroll books made from bamboo sticks: Because there is only limited space for characters on individual sticks, many of them were bound together with silk or leather string to form a scroll book. The custom of writing in columns from top to bottom and from right to left stems from this arrangement. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Writing on bronze, large seal script on the Shi Qiang plate, Fúfeng Xiàn, Shaanxi province, 10th century BC (replica). Bone and bronze are difficult to handle as writing media and are so costly that they are only suitable for ritual purposes. Bamboo, on the other hand, is available everywhere in China and is comparatively cheap. Gift from the China Printing Museum, Beijing. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Writing on bronze, large seal script on the Shi Qiang plate, Fúfeng Xiàn, Shaanxi province, 10th century BC (replica). Bone and bronze are difficult to handle as writing media and are so costly that they are only suitable for ritual purposes. Bamboo, on the other hand, is available everywhere in China and is comparatively cheap. Gift from the China Printing Museum, Beijing. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Characters on porcelain, blue calligraphy on white glazed porcelain, 17th century. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Characters on porcelain, blue calligraphy on white glazed porcelain, 17th century. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

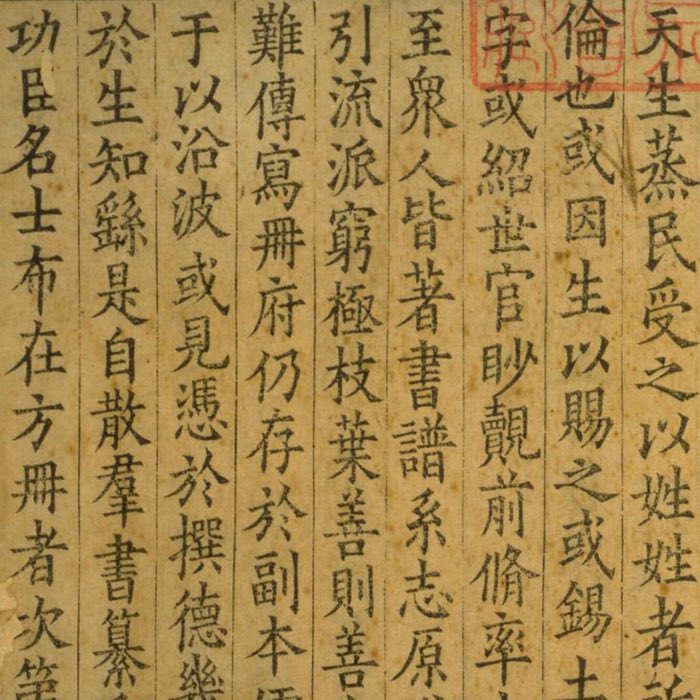

Jinchaeng, Poems and essays by Jong Jo handwritten in Chinese script, from the Korean colleciton. With the introduction of paper in the 3rd/4th century, a manuscript culture emerged in East Asia that continued to exist alongside the art of printing and is still practiced today. The educated classes, which essentially included the officials of the state bureaucracies, practiced calligraphy as a form of contemplation, copied and collected books and wrote commentaries on classical texts, as well as poems, stories and non-fiction. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Jinchaeng, Poems and essays by Jong Jo handwritten in Chinese script, from the Korean colleciton. With the introduction of paper in the 3rd/4th century, a manuscript culture emerged in East Asia that continued to exist alongside the art of printing and is still practiced today. The educated classes, which essentially included the officials of the state bureaucracies, practiced calligraphy as a form of contemplation, copied and collected books and wrote commentaries on classical texts, as well as poems, stories and non-fiction. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Map of today’s Chinese-speaking world. Dark green: Majority Chinese-speaking, Semi-dark green: Significant Chinese-speaking population, Light green: Status as an official or educational language. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The undeciphered Indus script

The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE) developed a script that remains undeciphered to this day. Known as the Indus script, it was used extensively on seals, pottery, amulets, and other artifacts. Its symbols often combine geometric shapes, animal motifs, and abstract designs, hinting at a sophisticated system of communication. The exact purpose and meaning of the script are still unknown due to the lack of bilingual texts or longer inscriptions, making decipherment particularly challenging.

Left: Spread of the Indus culture in the 26th century BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Right: Indus script on a stamp seal depicting a buffalo-horned figure surrounded by animals, dubbed the ‘Lord of the Beasts’ or ‘Paśupati’ seal (c. 2350–2000 BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The script’s widespread use across the Indus Valley suggests it played a significant role in administrative activities, perhaps related to trade, property ownership, or governance. Some researchers also speculate that it may have held ritual or religious significance, reflecting the spiritual practices of the Indus people. Despite decades of study, the Indus script’s undeciphered status highlights the complexities of early writing systems and underscores how much remains to be learned about one of the world’s earliest urban civilizations.

Three stamp seals and their impressions bearing Indus script characters alongside animals: “unicorn” (left), bull (centre), and elephant (right); Guimet Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0).

Indus characters from an impression of a cylinder seal discovered in Susa (modern Iran), in a stratum dated to 2400–2100 BCE; an example of ancient Indus–Mesopotamia relations. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0).

The Maya script

The Maya civilization, flourishing between 2000 BCE and the 16th century CE, developed one of the most sophisticated writing systems of the ancient world. The Maya script, also known as Maya glyphs, emerged as early as 300 BCE and remained in use until the Spanish conquest. It represents a unique combination of logograms (symbols representing words or morphemes) and syllabic signs, making it a mixed writing system capable of conveying both phonetic and semantic information.

Maya stucco glyphs displayed in the museum at Palenque, Mexico. Maya glyphs were highly complex and often carved into stone. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Map showing the extent of the Maya civilization (red), compared to all other Mesoamerica cultures (black), within Central America and southern North America. This map also shows the cities and cultural mainstays of the Maya, who did not have an empire but rather a group of loosely associated city-states. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Map showing the extent of the Maya civilization (red), compared to all other Mesoamerica cultures (black), within Central America and southern North America. This map also shows the cities and cultural mainstays of the Maya, who did not have an empire but rather a group of loosely associated city-states. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Maya script evolved from earlier Mesoamerican writing systems, including the Olmec and Zapotec scripts. Initially used for religious and ceremonial purposes, it later became a versatile medium for recording history, politics, astronomy, and everyday life. The glyphs adorned stelae, codices, pottery, and architectural elements, serving as a testament to the Maya’s intellectual and artistic achievements.

Two different ways of writing the word bʼalam ‘jaguar’ in the Maya script. First, as a logogram representing the entire word with the single glyph bʼalam, and then, phonetically using the three syllable signs bʼa, la, and ma. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Maya glyphs are arranged in paired columns, read from left to right and top to bottom. The system includes over 800 distinct signs, each with multiple variants, reflecting a high degree of visual and linguistic flexibility. The interplay between logograms and syllables allowed scribes to encode words and phrases in various ways, demonstrating their linguistic ingenuity.

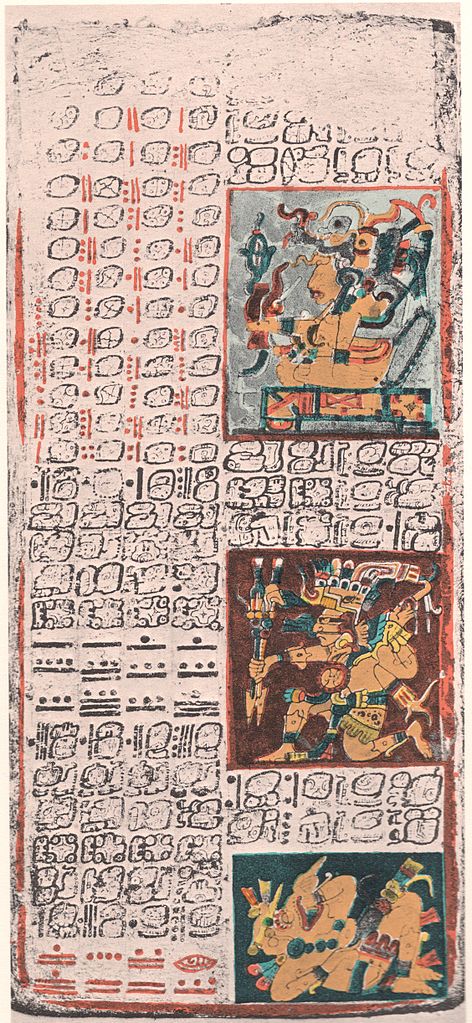

Yucatec Maya writing in the Dresden Codex, c. 11–12th century, Chichen Itza. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The script was used to write the Mayan languages, a family of related languages spoken throughout Mesoamerica. Inscriptions on monuments often commemorated events such as royal accessions, battles, and alliances, underscoring the political and social significance of the written word in Maya culture.

Detail of the Dresden Codex (modern reproduction). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

The decipherment of Maya glyphs began in earnest in the 19th and 20th centuries, culminating in breakthroughs by researchers like Tatiana Proskouriakoff and Yuri Knorosov. Knorosov demonstrated that the script combined logograms and syllabic elements, paving the way for further decipherment. Today, scholars can read most Maya inscriptions, unlocking insights into their history, religion, and scientific achievements.

Diego de Landa’s Maya alphabet was an early attempt at decipherment. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0).

The Phoenicians: The alphabet and its legacy

One of the most significant developments in the history of writing was the creation of the alphabet by the Phoenicians around 1200 BCE. The Phoenician script evolved from earlier Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions, which were themselves derived from Egyptian hieroglyphic principles. Proto-Sinaitic, developed by Semitic-speaking workers in the Sinai Peninsula around 1800–1500 BCE, adapted Egyptian symbols into a consonantal alphabet (abjad), marking the earliest known attempt at alphabetic writing.

Phoenician settlements and trade routes across the Mediterranean starting from around 800 BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

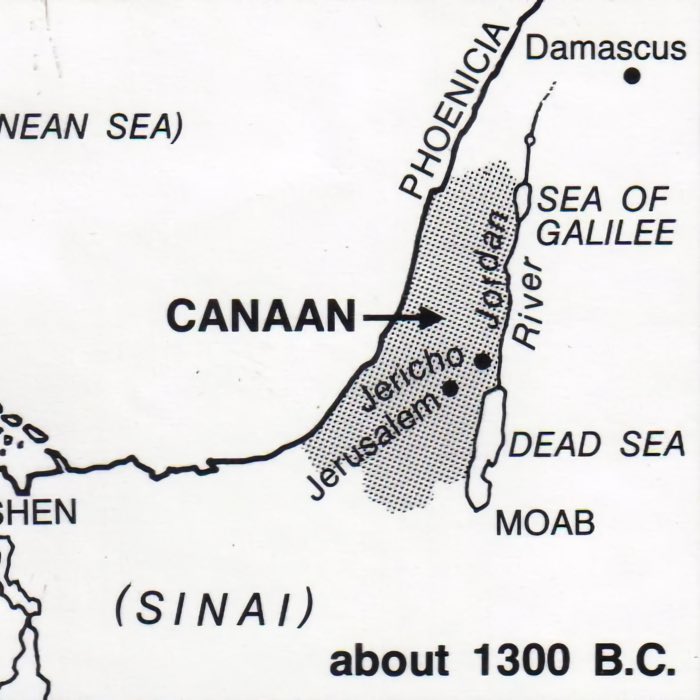

As Proto-Sinaitic spread northward into the Levant, it evolved into Proto-Canaanite (~1500–1200 BCE), a transitional script that further simplified and standardized the characters. By the time of the Phoenicians, this system was refined into the 22-character Phoenician alphabet, which exclusively represented consonants and was written from right to left.

The table below (sourceꜛ) illustrates this evolution, showcasing how Egyptian hieroglyphs influenced Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite scripts, which eventually gave rise to the Phoenician letters and consequently the Greek and Latin alphabets:

| Egyptian hieroglyphs | Reconstr. name | Meaning | Proto-Sinaitic | Proto-Canaanite | Phoenician | Greek | Latin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𓃾 | ʾālep, alp | ox, head of cattle |  |

|

𐤀 | Α, α | A, a |

| 𓉐 | bēt , bayt | house |  |

|

𐤁 | Β, β | B, b |

| 𓌙 | gīml, gamls | throwing stick (or camel) |  |

|

𐤂 | Γ, γ | G, g / C, c |

/ 𓉿 / 𓉿 |

dālet, dag | fish (or door) |   |

|

𐤃 | Δ, δ | D, d |

| 𓀠 | he, haw, hillul | praise (or window) |  |

|

𐤄 | Ε, ε | E, e |

/ 𓏲 / 𓏲 |

wāw, uph | hook or fowl |  |

|

𐤅 | (Ϝ, ϝ), Υ, υ | F, f / U, u / V, v / W, w / Y, y |

| 𓏭 | zayin, zayt | weapon (sword) |  |

|

𐤆 | Ζ, ζ | Z, , |

| 𓉗 / 𓈈 | ḥaṣr / ḥēt, ḫayt | courtyard, wall / thread |  |

|

𐤇 | Η, η | H, h |

| 𓄤? | ṭēt | wheel |  |

|

𐤈 | Θ, θ | Th, th |

| 𓂝 | yod, yad | arm, hand |   |

|

𐤉 | Ι, ι | I, i / J, j |

| 𓂧 | kāp | palm |  |

|

𐤊 | Κ, κ | K, k |

| 𓌅 | lāmed | goad |  |

|

𐤋 | Λ, λ | L, l |

| 𓈖 | mēm, maym | water |  |

|

𐤌 | Μ, μ | M, m |

| 𓆓 | nūn, naḥaš | serpent (or fish) |  |

|

𐤍 | Ν, ν | N, n |

| 𓊽 | śāmek | fish |   |

|

𐤎 | Ξ, ξ | X, x |

| 𓁹 | ʿayin | eye |  |

𐤏 | 𐤏 | Ο,ο / Ω, ω | O, o |

| 𓂋 | pē, pʿit | mouth or corner |  |

|

𐤐 | Π, π | P, p |

| 𓇑? | ṣādē | papyrus plant / field / land |  |

|

𐤑 | (Ϻ, ϻ) Σ, σ | S, s |

| 𓃻? | qōp | needle, nape or monkey |  |

|

𐤒 | (Ϙ, ϙ), Φ, φ | (Q, q) Ph, ph |

| 𓁶 | rēs, reš, raʾš | head |  |

|

𐤓 | Ρ, ρ | R, r |

/ 𓌓 / 𓌓 |

šīn / šimš | tooth or sun |  |

|

𐤔 | Σ, σ, ς | S, s |

| 𓏴 | tāw | mark |  |

|

𐤕 | Τ, τ | T, t |

The Phoenicians, renowned seafarers and traders, spread their alphabet across the Mediterranean through their extensive commercial networks. The simplicity and adaptability of the Phoenician script made it easy to learn, and its practical use for trade and administration enabled rapid adoption by neighboring cultures. The Phoenician script became the lingua franca of the ancient Mediterranean and eventually influenced the development of the Greek and Latin alphabets, forming the foundation of many modern writing systems used across Europe and the Americas.

Left: The Mesha Stele, or Moabite Stone, is a stele dated around 840 BCE containing a significant Canaanite inscription in the name of King Mesha of Moab (a kingdom located in modern Jordan). It is written in a variant of the Phoenician alphabet. The brown fragments are pieces of the original stele, whereas the smoother black material is a reconstruction from the 1870s. Louvre. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Right: Drawing of the Mesha Stele (or Moabite Stone) by Mark Lidzbarski, published 1898: The shaded area represents pieces of the original stele, whereas the plain white background represents the reconstruction from the 1870s based on the squeeze. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Phoenician alphabet similar to that used on the Mesha Stele. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Greek alphabet

The Greeks adopted and modified the Phoenician alphabet around 800 BCE, adding vowels and creating a more versatile writing system. They assigned symbols from the Phoenician script that represented sounds not present in Greek to represent vowel sounds. For instance, the Phoenician letter ‘aleph became the Greek alpha (A), and he became epsilon (E). The Greeks also changed the direction of writing from right-to-left to left-to-right, a practice that became standard and influenced later writing systems, including Latin.

Early Greek alphabet on pottery, probably early 6th c. BCE, National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

This map of the States of the Diadochi, c. 300 BC, shows the territories of the successors of Alexander the Great. The Greek alphabet played a crucial role in the spread of Greek culture and language across the Hellenistic world. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Greek alphabet was instrumental in the development of Greek culture, particularly its rich literary and philosophical traditions. It enabled the recording of epic poetry, such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and facilitated the systematic development of philosophy, science, and history. Texts by thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Herodotus owe their preservation and dissemination to the adaptability of the Greek alphabet.

| Greek letter | Traditional Latin transliteration | Greek letter | Traditional Latin transliteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Α α | A a | Ν ν | N n |

| Β β | B b | Ξ ξ | X x |

| Γ γ | G g | Ο ο | O o |

| Δ δ | D d | Π π | P p |

| Ε ε | E e | Ρ ρ | R r, Rh rh |

| Ζ ζ | Z z | Σ σ/ς | S s |

| Η η | Ē ē | Τ τ | T t |

| Θ θ | Th th | Υ υ | Y y, U u |

| Ι ι | I i | Φ φ | Ph ph |

| Κ κ | C c, K k | Χ χ | Ch ch, Kh kh |

| Λ λ | L l | Ψ ψ | Ps ps |

| Μ μ | M m | Ω ω | Ō ō |

Marble stele inscribed with a decree of the Athenian boulē, c. 440–425 BC. The inscription reads: Ἔδοξεν τῇ Βουλῇ καὶ τῷ Δήμῳ, “The Council and the Citizens have decided”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Latin alphabet

The Romans later adopted the Greek alphabet through the intermediary of the Etruscan script. This process began around the 7th century BCE, as the Etruscans, a civilization in central Italy, adopted and modified the Greek alphabet for their own language. They simplified and altered some of the symbols, maintaining the left-to-right writing direction introduced by the Greeks. The Romans later borrowed and further adapted the Etruscan script to suit the sounds of Latin. The early Latin alphabet consisted of 21 letters, with additional letters, such as G and later Y and Z, introduced to represent sounds in borrowed Greek words.

The Duenos inscription, dated to the 6th century BC, shows the earliest known form of the Old Latin alphabet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Latin alphabet became a tool of Roman administration, law, and culture, spreading throughout the vast territories of the Roman Empire. Its simplicity and adaptability facilitated its adoption by diverse linguistic communities within the empire. Over time, the Latin alphabet was further refined and standardized, forming the basis of modern alphabets used in English, French, Spanish, and many other languages.

Today’s distribution of the Latin script. Dark green: Latin script is the sole official (or de facto official) national script. Light green: Latin script is a co-official script at the national level. Grey: Latin script is not officially used. Latin-script alphabets are sometimes extensively used in areas coloured grey due to the use of unofficial second languages, such as French in Algeria and English in Egypt, and to Latin transliteration of the official script, such as pinyin in China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Middle Ages: Manuscripts and scribes

During the Middle Ages, the preservation and dissemination of knowledge relied heavily on handwritten manuscripts. Monasteries and scriptoria became centers of learning, where monks meticulously copied religious texts, classical works, and legal documents. This period saw the creation of illuminated manuscripts, which combined text with intricate illustrations, enhancing the beauty and accessibility of written works. The labor-intensive nature of manuscript production limited the spread of literacy, but it also ensured the survival of crucial texts through turbulent times.

The printing revolution: Gutenberg and beyond

The further development of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century revolutionized the production of written texts. Gutenberg’s press used movable metal type, allowing for the mass production of books at unprecedented speed and lower cost. The spread of printed materials facilitated the dissemination of knowledge, ideas, and literacy, contributing to the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution. The printing press democratized access to information, laying the groundwork for the modern knowledge-based society.

Psalterium Benedictinum, the 150 biblical psalm texts for the Order of Saint Benedict (second, altered edition of the 1457 Mainzer Psalter), Mainz, Johannes Fust and Peter Schöffer, 1459. Print with four colors and two different font sizes on parchment. The musical notes were entered by hand. Gutenberg-Museum Mainz.

Psalterium Benedictinum, the 150 biblical psalm texts for the Order of Saint Benedict (second, altered edition of the 1457 Mainzer Psalter), Mainz, Johannes Fust and Peter Schöffer, 1459. Print with four colors and two different font sizes on parchment. The musical notes were entered by hand. Gutenberg-Museum Mainz.

Modern Era: Digital writing and information exchange

In the modern era, writing has undergone another transformation with the advent of digital technology. The internet and digital communication tools have revolutionized how information is created, shared, and accessed. Emails, social media, and online publications enable instantaneous communication across the globe, furthering the exchange of knowledge and ideas. Digital writing has expanded the reach of literacy, allowing more people than ever before to participate in the global dialogue.

Civilizational role of writing

The invention of writing catalyzed a series of transformative changes in human societies, enabling the rise of complex civilizations and reshaping social, economic, and intellectual structures.

Administration and governance

Writing allowed for the establishment of centralized administration and governance, as rulers could issue directives, record laws, and maintain detailed accounts of resources. Legal codes such as the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) exemplify how writing was used to formalize justice and consolidate state authority. By providing a permanent record of decrees and transactions, writing systems enhanced accountability and reduced the ambiguities inherent in oral communication.

Economic development

The development of writing coincided with the growth of trade and commerce. Written records facilitated the tracking of transactions, the calculation of debts, and the management of inventories. Early writing systems, such as Mesopotamian cuneiform and Chinese oracle bone inscriptions, reveal the critical role of writing in economic exchanges and the coordination of large-scale trade networks.

Preservation of knowledge

Writing became humanity’s first external memory system, enabling the preservation and accumulation of knowledge across generations. Oral traditions, while rich and dynamic, were limited by the frailties of human memory and the contingencies of transmission. Writing overcame these limitations, allowing for the creation of enduring records in fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy.

The written transmission of knowledge also allowed societies to reflect on their histories, codify their cultural practices, and develop shared identities. Texts such as the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Vedic hymns of ancient India exemplify the use of writing to preserve spiritual and cultural heritage.

Intellectual importance of writing

The advent of writing transformed not only the practical aspects of human life but also profoundly reshaped intellectual activity, enabling new forms of thought, communication, and creativity. Writing transcended the limitations of oral traditions, allowing for the systematic development of abstract concepts, complex reasoning, and the preservation of intellectual heritage across generations and geographies.

Abstract reasoning and systematic thought

Writing externalized human thought, enabling individuals and communities to reflect critically on ideas. This externalization allowed for the development of more complex and abstract reasoning. Philosophical and scientific traditions, such as those found in ancient Greece, India, and China, were profoundly influenced by the ability to document, critique, and refine ideas in written form.

For example, the works of Aristotle, Confucius, and the authors of the Upanishads were not only shaped by oral traditions but were also deeply influenced by the permanence and precision that writing afforded. The written word facilitated the systematic exploration of metaphysics, ethics, mathematics, and logic, laying the foundation for intellectual traditions that continue to shape human thought.

Creation of literature

Writing transformed storytelling into literature, enabling the creation of enduring texts that explored the human condition, morality, and the divine. Epics such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and the Mahabharata exemplify the power of writing to elevate oral traditions into complex, multi-layered narratives.

These literary works not only preserved cultural values but also encouraged the development of language as an art form. Writing allowed for experimentation with poetic structure, metaphor, and symbolism, enriching the expressive capacity of language.

Philosophical and religious texts

Writing became the primary medium for recording religious and philosophical texts, enabling the systematic articulation and dissemination of beliefs. Texts such as the Torah, the Quran, the Buddhist Pali Canon, and the Daoist Dao De Jing exemplify how writing served as a vehicle for spiritual teachings and ethical systems.

By preserving these teachings in written form, societies ensured their transmission across time and space, enabling the growth of religious and philosophical communities and the cross-cultural exchange of ideas.

Scientific and technical knowledge

The documentation of scientific and technical knowledge in writing transformed the way humanity understood and interacted with the natural world. Early records of astronomical observations, mathematical calculations, and medical practices, such as those found in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Mayan, and Indian texts, demonstrate the importance of writing in advancing human understanding.

By creating a permanent repository of knowledge, writing enabled cumulative progress. Subsequent generations could build on the discoveries of their predecessors, leading to significant advances in fields ranging from engineering to medicine.

Writing and cultural exchange

Writing also facilitated the exchange of ideas and cultures across vast distances. The invention of writing systems coincided with the development of trade networks, such as the Silk Road, which linked civilizations from East Asia to the Mediterranean. Written records, treaties, and correspondence enabled cross-cultural interactions that enriched art, science, and religion.

The spread of writing systems themselves – such as the adaptation of the Phoenician alphabet into Greek and Latin scripts – demonstrates how writing was both a tool of cultural preservation and a catalyst for cultural evolution.

Conclusion

The development of writing was indeed a transformative event in human history, fundamentally altering the structure of societies and the trajectory of intellectual development. From its origins in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica, writing evolved into a universal tool for administration, commerce, and intellectual exploration. It enabled the preservation and transmission of knowledge, the articulation of complex ideas, and the creation of enduring cultural and spiritual traditions.

In my opinion, the civilizational and intellectual importance of writing cannot be overstated. It has served as humanity’s most enduring technology for communication, shaping the way we think, learn, and connect across time and space. As we continue to develop new forms of communication in the digital age, the legacy of writing reminds us of the profound impact of the written word on human history and progress.

References and further reading

- Harald Haarmann, Geschichte der Schrift, 2002, C.H.Beck, ISBN: 9783406479984

- Harald Haarmann, Universalgeschichte der Schrift, 1990, Campus, ISBN: 9783593343464

- Michael Stolz, Adrian Mettauer, Yvonne Dellsperger, André Schnyder, Hendrik Kuschel, Buchkultur im Mittelalter - Schrift, Bild, Kommunikation, 2005, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 9783110189223

- Martin Kuckenburg, Wer sprach das erste Wort? - die Entstehung von Sprache und Schrift, 2010, THEISS, ISBN: 9783806223309

- Harald Haarmann, Early civilization and literacy in Europe – An inquiry into cultural continuity in the mediterranean world, 2012, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 9783110869057

- Schmandt-Besserat, D., How Writing Came About, 1997, University of Texas Press, ISBN: 978-0292777040

- Robinson, A., Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199567782

- Coulmas, F., Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis, 2003, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521787376

- Goody, J., The Interface Between the Written and the Oral, 1987, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521337946

- Houston, S. D., The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521728263

- Sass, B., The Alphabet at the Turn of the Millennium: The West Semitic Alphabet, ca. 1150-850 BCE, 2009, Institute of Archaeology, ISBN: 978-9652660213

- Powell, B. B., Homer and the Origin of the Greek Alphabet, 1991, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521589079

- Daniels, P. T., & Bright, W., The World’s Writing Systems, 1996 Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195079937

- Wikipedia article on the history of writingꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Chinese charactersꜛ and Written Chineseꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Indus scriptꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Maya scriptꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Proto-Sinaitic scriptꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Phoenician alphabetꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Mesha Steleꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Archaic Greek alphabetsꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Greek alphabetꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the History of the Latin scriptꜛ

comments