The mythological roles of ‘angels’ in East and West

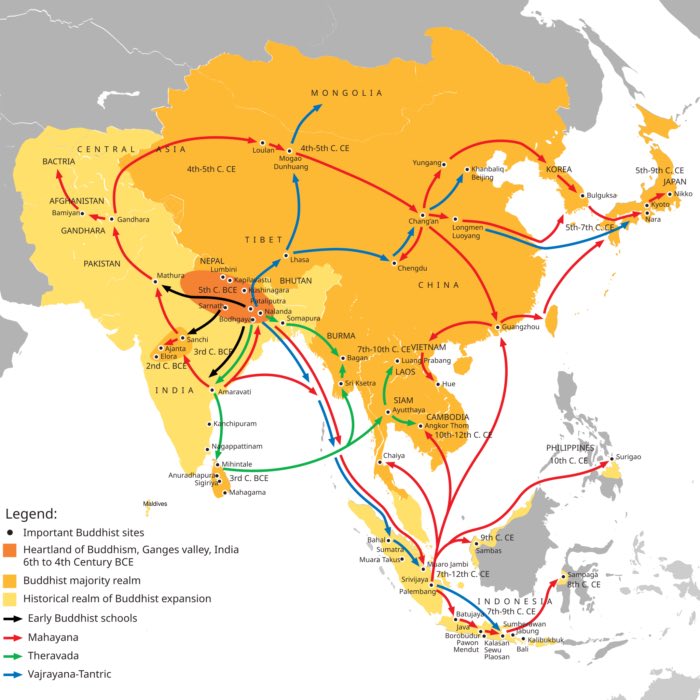

Angels, as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal, have captured the human imagination across cultures and religions. In the Abrahamic traditions, angels are messengers, guardians, and executors of divine will, often depicted as ethereal beings imbued with spiritual power. Their origin, however, is deeply rooted in ancient Near Eastern and Hellenistic traditions, which influenced the conceptualization of angels in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Simultaneously, analogous figures in Buddhism and Asian traditions, influenced in part by Hellenistic cultural exchanges after Alexander the Great, reveal the interconnectedness of cultural and religious ideas in the ancient world.

Archangel Gabriel from the Annunciation, Scene on a set of Royal Doors, Russia, 18th/19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Archangel Gabriel from the Annunciation, Scene on a set of Royal Doors, Russia, 18th/19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Origins of angels in antiquity

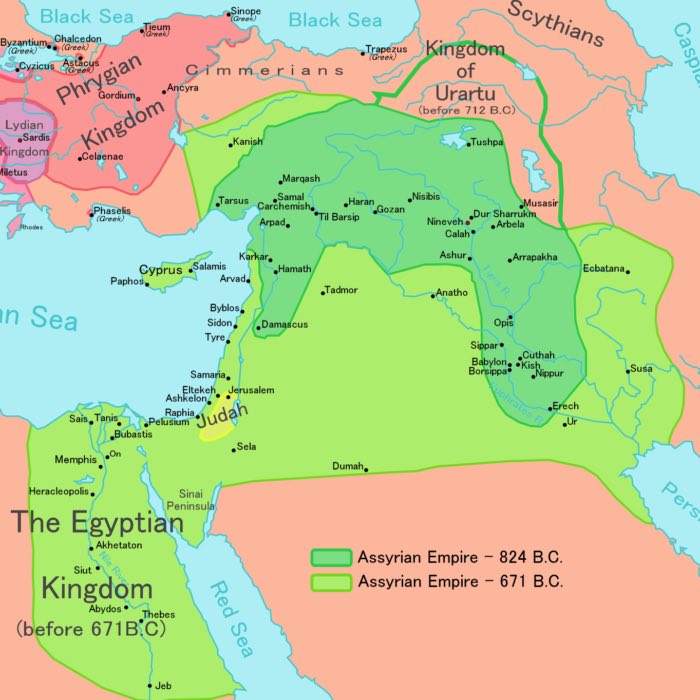

The concept of angels, as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal, has deep roots in the mythologies and cosmologies of the ancient Near East, later evolving into the angelic figures of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These beings, while distinct in each tradition, share thematic and functional similarities with earlier Near Eastern, Persian, and Hellenistic intermediaries.

Ancient Near Eastern roots

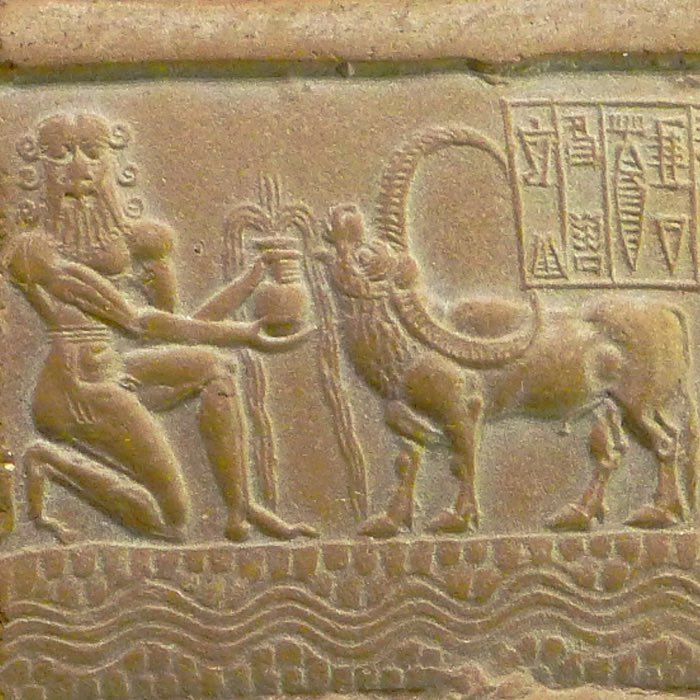

In ancient Mesopotamian and Ugaritic traditions, intermediary beings played significant roles in the interaction between gods and humanity. In the Ugaritic Baal Cycle (13th century BCE), divine messengers (mlak in Ugaritic, related to the Hebrew mal’akh, “messenger”) were sent by higher gods such as Baal to communicate with other deities or humans. These beings followed a formulaic process: they were dispatched by their divine master, made long journeys accompanied by light and fire phenomena, delivered their messages with reverence, and returned with a reply.

Similarly, in Mesopotamian mythologies, gods used intermediaries to execute their will. These beings, often called ilum (divine beings) or ishtaru, could act as protectors or, depending on their tasks, bringers of misfortune. The visual representation of these beings in Mesopotamian art frequently depicted them as anthropomorphic figures with wings, symbolizing their supernatural nature and swiftness. This imagery likely influenced later representations of angels in Abrahamic traditions.

Four-winged Assyrian genius from the palace of Dur Šarrukin, around 710 BCE, Iraqi National Museum Baghdad. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

The concept of personal protectors also appears in Mesopotamian thought. Each individual was believed to have a fravashi or guardian spirit that could guide or abandon them based on their actions, foreshadowing the notion of guardian angels in later Abrahamic faiths.

Relief depicting the Faravahar in the city of Persepolis, which served as the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 3.0)

Relief depicting Ashur inside of a winged disk, located at the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II in the city of Nimrud, c. 865–850 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 3.0)

Angel-like beings in Hellenistic culture

Greek mythology, long before the Hellenistic period, already featured intermediary figures such as daimones, Hermes, and Nike. These beings were deeply ingrained in Greek religious and cultural traditions, serving as messengers, guides, and protectors, and were portrayed as bridging the divine and human realms.

Following Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BCE, Greek culture entered into a profound exchange with the traditions of the Near East, Persia, and Central Asia. This interaction did not alter the foundational roles of figures like daimones or Hermes within Greek mythology. However, it introduced a rich synthesis of ideas that significantly influenced the representation of intermediary beings in other cultural and religious systems, including Judaism, Christianity, and, as we will explore later, Buddhist and Indian artistic traditions.

Daimones

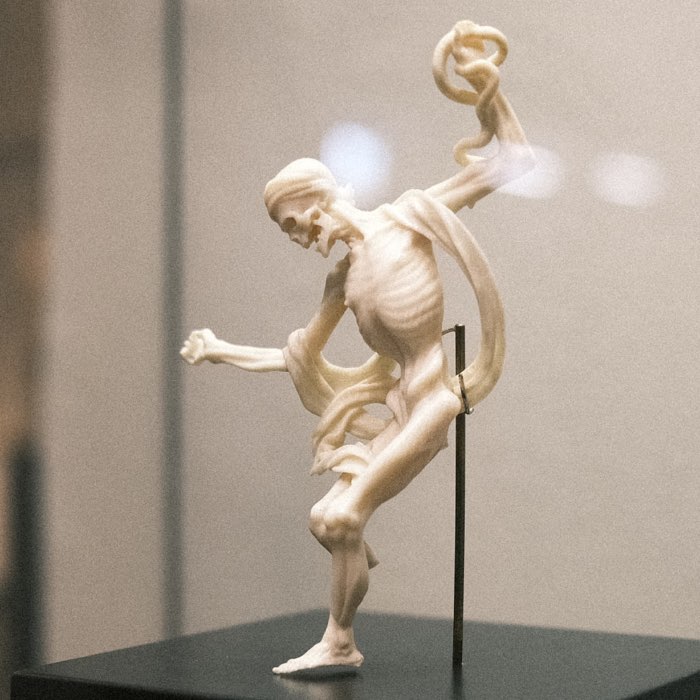

Daimones, as described by Hesiod, were spirits derived from the virtuous dead of the Golden Age, acting as moral guides and protectors of humans. Their Roman counterpart, the genius, often depicted with wings, symbolized personal and familial guardianship. These figures, operating as intermediaries, share functional similarities with angels, albeit rooted in the distinct Greek and Roman cosmologies that predate Hellenistic cultural exchanges.

Winged genius (right) facing a woman (left) with a tambourine and mirror, from southern Italy, about 320 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 2.5)

Hermes as messenger

Hermes (Mercury in Roman mythology) was already firmly established in Greek religious tradition as the swift and cunning divine messenger. His winged sandals and caduceus symbolized communication and mediation, roles that bore conceptual similarity to those of angels in later Jewish and Christian traditions. However, his influence on the visual representation of angels likely emerged indirectly through cultural reinterpretations during the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Hermes, copy of a Roman bronze recovered from the Villa of the Papyri, Naples, Getty Villa. Hermes’ winged sandals symbolize his role as a divine messenger. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Nike: The winged victory

Nike, the goddess of victory, epitomized divine favor and success. Frequently depicted as a winged figure with a wreath or palm branch, her iconography influenced Roman representations of Victoria and later inspired Christian portrayals of angelic figures as bearers of divine triumph. This evolution highlights how Greek religious imagery, independent of Near Eastern concepts, permeated later traditions.

Flying Nike, Myrina, 2nd-1st century BCE, Antikensammlung Berlin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 3.0)

Angelic intermediaries in Hellenistic religious cults

Hellenistic and Roman religious practices expanded upon the concept of intermediary beings. Cults dedicated to deities like Zeus Hypsistos or Men (a moon god of potential Iranian origin) included invocations to ángeloi as messengers or protectors, bridging divine and mortal realms. These beings, rooted in local and syncretic practices, influenced early Christian thought as theologians grappled with defining acceptable veneration of angels distinct from pagan practices.

Aphrodite: Example of interconnections and cultural fluidity in the ancient world

While Nike and other angel-like figures in Greek mythology seem to have no connections to any Meospotamian deities, there is one goddess whose origins are deeply rooted in the Near East: Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty. Her worship and iconography bear notable similarities to Inanna-Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of love, fertility, and war, as mediated through the Phoenician deity Astarte. Ancient sources, such as Pausanias, suggest that the cult of Aphrodite entered Greece through Phoenician trade and cultural exchange, particularly in regions like Cyprus and Cythera. Titles such as Ourania (“Heavenly”), associated with Aphrodite, reflect Inanna-Ishtar’s role as the “Queen of Heaven”, while Aphrodite’s early depictions as a goddess bearing arms, especially in Sparta, echo Inanna-Ishtar’s dual role as a deity of love and war.

Left: Small statue, that may represent the goddess Ishtar, showing her wearing a crown and clutching her breasts, circa. 1300-1100 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) - Middle: Statue of Aphrodite from Cyprus, showing her wearing a cylinder crown and holding a dove, 450 - 425 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Ludovisi Cnidian Aphrodite, Roman marble copy (torso and thighs) with restored head, arms, legs and drapery support; restorer: Ippolito Buzzi (1562–1634). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Aphrodite’s mythological birth from the sea foam, described in Hesiod’s Theogony, may also carry echoes of Inanna-Ishtar’s symbolic associations with primordial waters, a motif in Mesopotamian creation myths. In these narratives, water often represents fertility and cosmic renewal, themes central to both goddesses. The eighth century BCE Orientalizing Age further solidified these connections, as Greek religion assimilated Mesopotamian and Phoenician motifs. Aphrodite thus exemplifies the complex syncretism of Near Eastern and Greek traditions, illustrating how cross-cultural exchanges enriched ancient Mediterranean religion.

Angels in early Judaism and the influence of Hellenism

The origins of angels in early Jewish thought predate Hellenistic influence but evolved significantly under the cultural and philosophical milieu of the Hellenistic world.

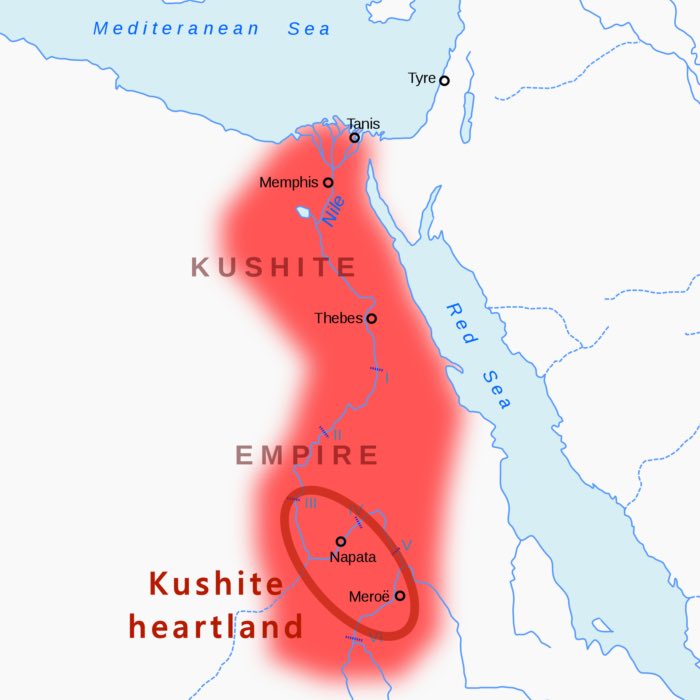

Persian and Near Eastern roots of Jewish angelology

Jewish angelology drew from Near Eastern and Persian traditions during the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE). The Zoroastrian concept of hierarchical intermediary beings, such as the amesha spenta and fravashis, introduced structured notions of divine messengers and protectors. These parallels are evident in Jewish texts like the Book of Daniel, where angels such as Michael and Gabriel act as divine agents in a cosmic struggle.

Relief of an angel at Taq-e Bostan, a site with a series of large rock reliefs from the era of the Sassanid Empire of Persia, carved around the 4th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

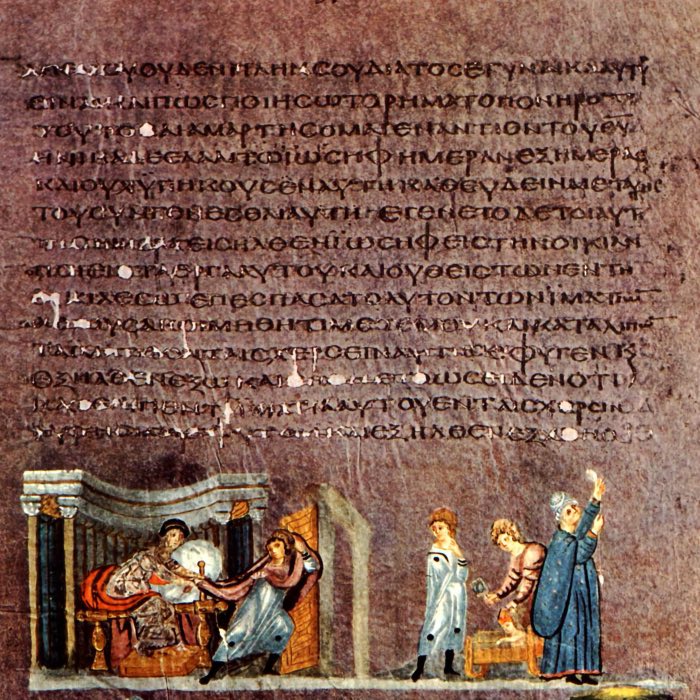

Hellenistic contributions to the Jewish angelology

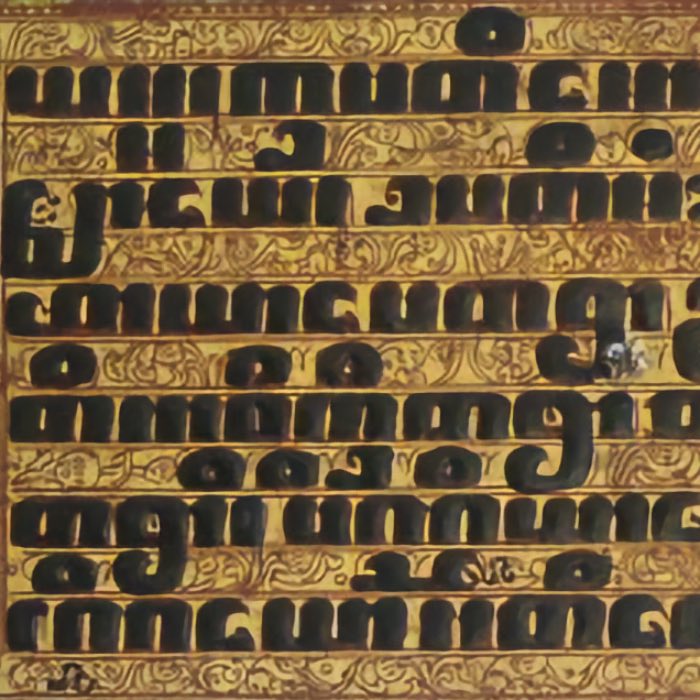

Under Hellenistic influence, Jewish angelology further developed, incorporating Greek ideas about daimones and the philosophical role of intermediaries. The Septuagint translated the Hebrew term mal’akh (messenger) as ángelos, aligning Jewish angelic figures with Greek intermediary beings. Apocalyptic texts, such as the Book of Enoch, reflect this syncretism by elaborating on angelic hierarchies and functions, blending Jewish, Persian, and Greek concepts.

Angels with butterfly wings restoring life in a mural from the Dura Europos synagogue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

2nd or 3rd-century carving of the Menorah being attended by angels, including angels who may represent the seasons of the year. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

6th century zodiac mosaic from the Beth Alpha Synagogue. At the corners are winged female angels, perhaps representing the seasons. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Transition to Christian angelology

Early Christianity inherited and expanded Jewish angelology, integrating it into a broader Hellenistic framework. The New Testament emphasizes angelic roles in pivotal moments of Jesus’ life, such as the Annunciation (Luke 1:26–38) and Resurrection (Mark 16:5–7). Christian theologians, influenced by Greek philosophy and Jewish traditions, later systematized angelic hierarchies, culminating in the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius, which shaped Christian thought for centuries.

Angels in Christianity and Islam

Christianity and Islam inherited and expanded upon Jewish angelology, incorporating angels into their theological and cosmological frameworks while adapting their roles to the needs of their respective faiths.

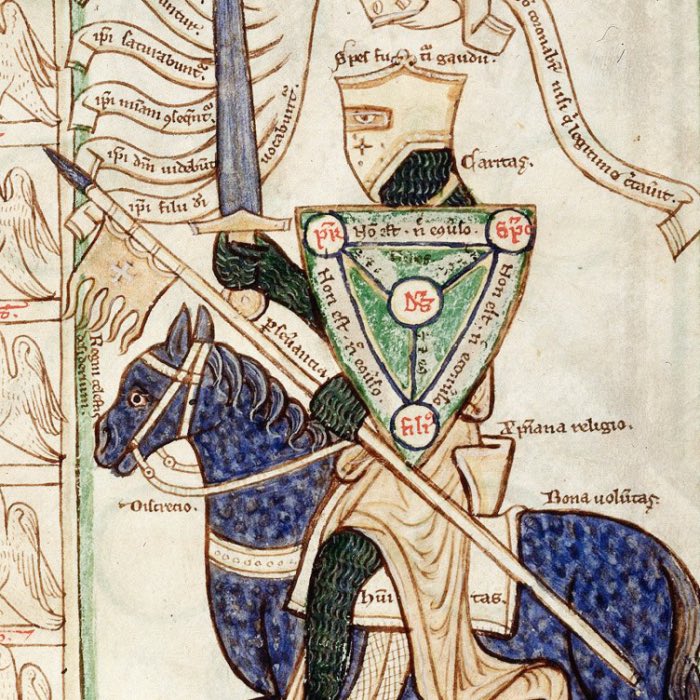

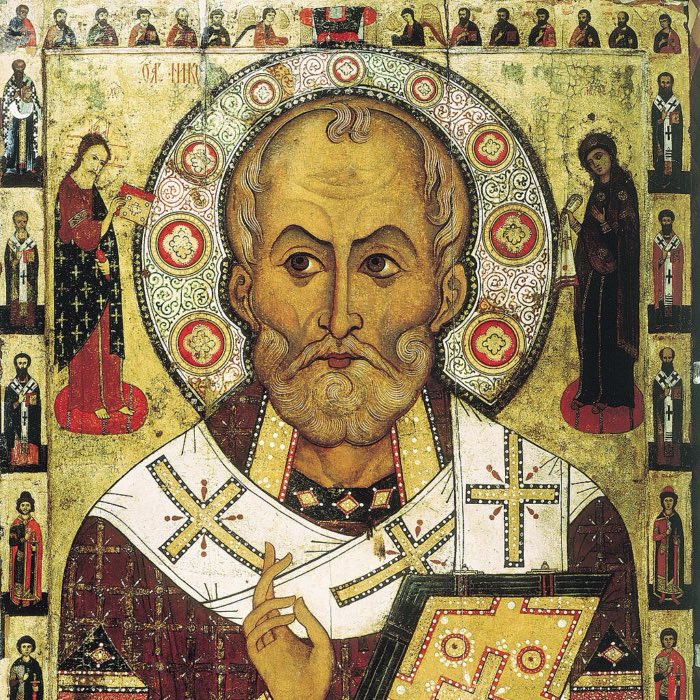

Christianity

In Christianity, angels are seen as servants of God, guiding and protecting humanity while worshipping the divine. The New Testament emphasizes their roles as messengers, such as the angel Gabriel announcing the birth of Jesus to Mary (Luke 1:26–38). Christian tradition also organizes angels into a hierarchy, famously articulated by Pseudo-Dionysius in the 5th century CE. His Celestial Hierarchy divides angels into nine orders, ranging from seraphim and cherubim to ordinary guardian angels.

Left: Christian interpretation of Archangel Michael, Andrei Rublev, c. 1408. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Christian interpretation of Gabriel, icon, Byzantine, c. 1387–1395. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Archangel Michael trampling the devil underfoot, Simon Ushakov, 1676, icon, Moscow, Russia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Miracle of the Archangel, Michael at Chonae, Northern Russia, 17th century, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Miracle of the Archangel, Michael at Chonae, Northern Russia, 17th century, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Archangel Michael Archistrategos (Voivode) as Apocalyptic Horseman, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Archangel Michael Archistrategos (Voivode) as Apocalyptic Horseman, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Annunciation (detail), Emmanuel Tzanes, Venice, Italian-Cretan, 1640, egg tempera on wood. And the angel said to her: ‘Do not be afraid, Mary! You have found favor with God. Behold, you will conceive and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus.’ - Luke 1, 30-31. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Annunciation (detail), Emmanuel Tzanes, Venice, Italian-Cretan, 1640, egg tempera on wood. And the angel said to her: ‘Do not be afraid, Mary! You have found favor with God. Behold, you will conceive and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus.’ - Luke 1, 30-31. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

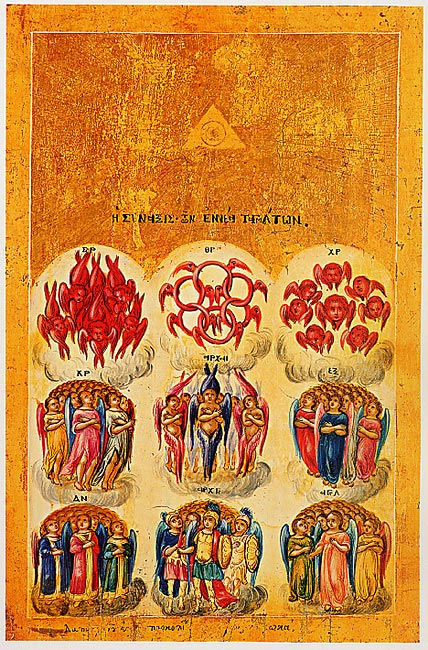

Christian angelology: The Nine Choirs of Angels on a Greek icon, 18th century. The Nine Choirs of Angels is a Christian division of the biblical angelic beings into nine graded orders dating back to the early Middle Ages. The angels and heavenly powers often mentioned in the writings of the Old and New Testaments without a clearly recognizable profile were thus differentiated from one another and brought into a hierarchical system. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Islam

Islamic angelology, derived from the Quran and Hadith, portrays angels as beings of pure light who execute God’s commands. Prominent angels include Jibril (Gabriel), who revealed the Quran to Muhammad; Israfil, who will blow the trumpet on the Day of Judgment; and Malik, the guardian of Hell. Angels are central to Islamic cosmology and serve as moral exemplars, devoid of free will and sin.

A depiction of Muhammad receiving his first revelation from the Angel Jibril (Gabriel). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

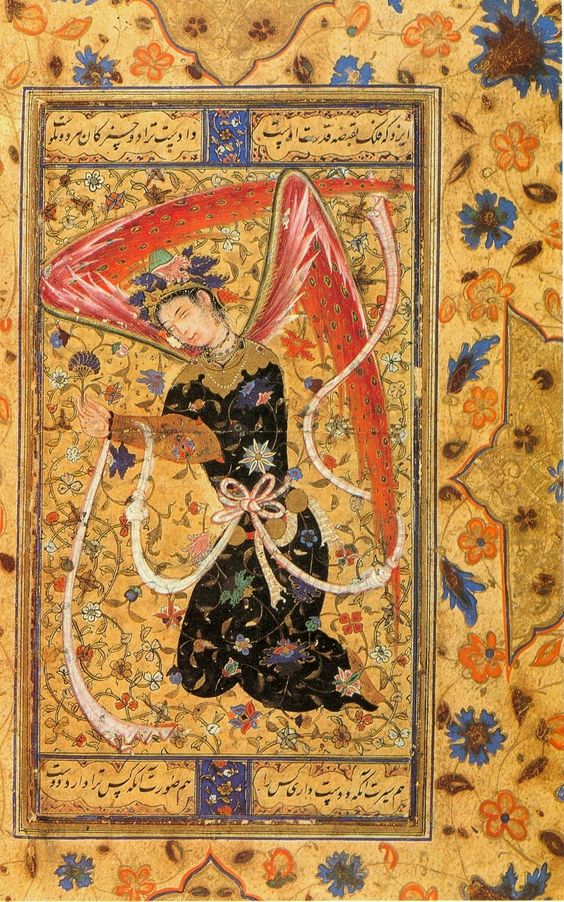

Left: The angel Isrāfīl in a 14th-century Qazwīnī manuscript. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Islamic depiction of an angel in a Persian miniature, 1555. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: The Angels meet Adam, the prototypical human being, before they are being tested to prostrate themselves before Adam. They share, albeit to a lesser degree, the defiant reaction of Iblis, the future devil, who, in contrast to the angels, is depicted with a dark face. Painting from a manuscript of the Manṭiq al-ṭayr (The Conference of the Birds) of Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār, Iran, Shiraz, 1494. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Muhammad advancing on Mecca, with the angels Gabriel, Michael, Israfil and Azrail, Siyer-i Nebi, 16th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Angelic parallels in Buddhism and Asian traditions

While angels are absent as a distinct category in Buddhist and Asian traditions, there are analogous beings that perform intermediary roles and share functional similarities with angels. These figures were influenced by indigenous cultural developments as well as cross-cultural interactions, particularly in the Gandharan region following Alexander’s conquests.

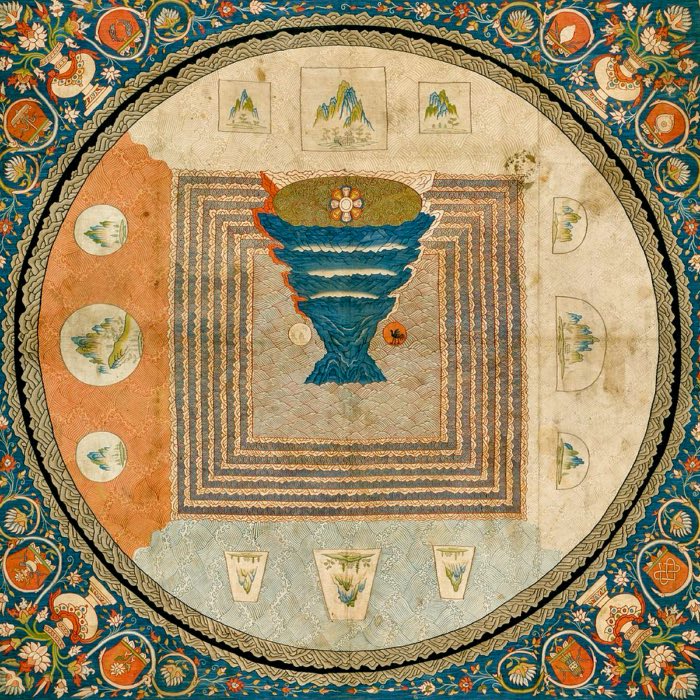

Devas and bodhisattvas in Buddhism

In Buddhism, devas are celestial beings who inhabit heavenly realms within the Buddhist cosmology. While they are not eternal or omnipotent like angels in Abrahamic traditions, they serve protective and inspirational roles, often appearing as patrons of the Buddha and his teachings. For example, the deva Indra (Sakka in Pali) is depicted as a guardian of the Buddha and a supporter of righteousness.

Indra (‘Chief of the Gods’), gilt-copper, 16th century, Nepal. In the earliest Vedic literature, Devas are benevolent supernatural beings. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Bodhisattvas, particularly in Mahayana Buddhism, are spiritually advanced beings who delay their own enlightenment to assist others on the path to liberation. Figures such as Avalokiteshvara (the Bodhisattva of Compassion) bear some resemblance to angels in their mediating role between the transcendent and the mundane.

Head of a Bodhisattva, Gandhara, around 4th century, terracotta, Asian Civilisations Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

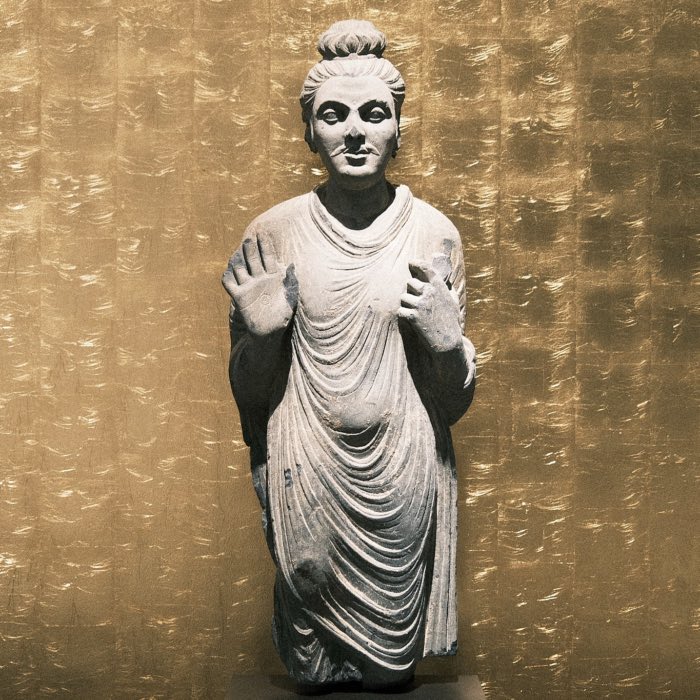

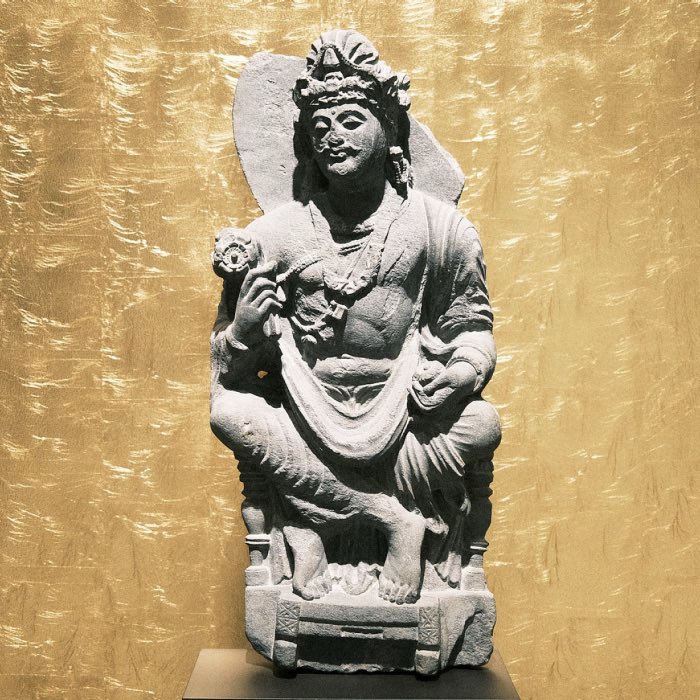

Gandharan influence

The Gandharan region, encompassing parts of modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, became a crossroads of Greek, Indian, and Persian cultures after Alexander’s campaigns. Gandharan Buddhist art, influenced by Hellenistic aesthetics, introduced new iconographic elements that resemble angelic figures. Winged beings, reminiscent of Greek representations of Eros or Nike, appear in Gandharan sculptures, often as attendants to the Buddha or Bodhisattvas.

Garland Holder with a Winged Celestial, Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara), schist, mid-1st century. Such volutes were affixed to the drums of small stupas to support garlands of flowers. These auspicious figures are among the earliest forms of sculptural embellishment found at Gandharan Buddhist sites. Source: Met Museumꜛ (license: public domain)

Atlas with wings, Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara), schist, 2nd-3rd c., Kushan period. Source: The British Museumꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0ꜛ)

This artistic synthesis suggests that the Hellenistic concept of celestial intermediaries contributed to the visual and symbolic vocabulary of Buddhist art, creating a unique blend of Greek and Indian spiritual motifs.

Dragons and Nāgas

In Asian traditions, serpentine, dragon-like beings known as nāgas also occupy roles analogous to angels. Nāgas are often depicted as protectors of sacred spaces and guardians of treasures, similar to the protective role of angels. In Buddhist mythology, a nāga shelters the meditating Buddha from a storm, reflecting the theme of divine guardianship.

Crowned golden nāga-woodcarving at Keraton Yogyakarta, Java. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Garuda: The divine bird

Garuda, a mythical bird both in Hindu and Buddhist traditions, offers another striking example of an angel-like figure. In Hindu mythology, Garuda is the mount (vahana) of Vishnu, symbolizing speed, strength, and divine authority. Often depicted with a human body, bird wings, and a beak-like nose, Garuda is revered as a protector and enemy of serpents (nāgas), embodying themes of cosmic order and divine guardianship.

In Buddhist mythology, Garuda retains its protective qualities but is also integrated into the Buddhist cosmology, where it often serves as a guardian figure and a symbol of overcoming ignorance and evil. Garuda’s iconography and role as a celestial being align with angelic functions in Abrahamic traditions, as it serves as both a protector and an intermediary between the divine and the mortal realms.

Garuda in Koh Ker style, sandstone, 1st half of 10th century, Khmer, Angkor period. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 2.0)

Garuda at Durbar square in Kathmandu, Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 3.0)

Comparative analysis

The concept of intermediary beings, whether angels in Abrahamic religions or devas and Bodhisattvas in Buddhism, reveals a universal human inclination to imagine agents that bridge the gap between the divine and the mortal. Despite differences in theological frameworks, these beings share key characteristics:

- Mediators: They serve as conduits between higher spiritual realms and the human world.

- Guardians: They protect individuals, sacred spaces, or cosmic order.

- Messengers: They convey divine will or moral guidance.

The cultural exchange facilitated by Hellenistic expansion further highlights the permeability of religious ideas, as seen in the visual and symbolic parallels between Gandharan devas and Western angels.

Conclusion

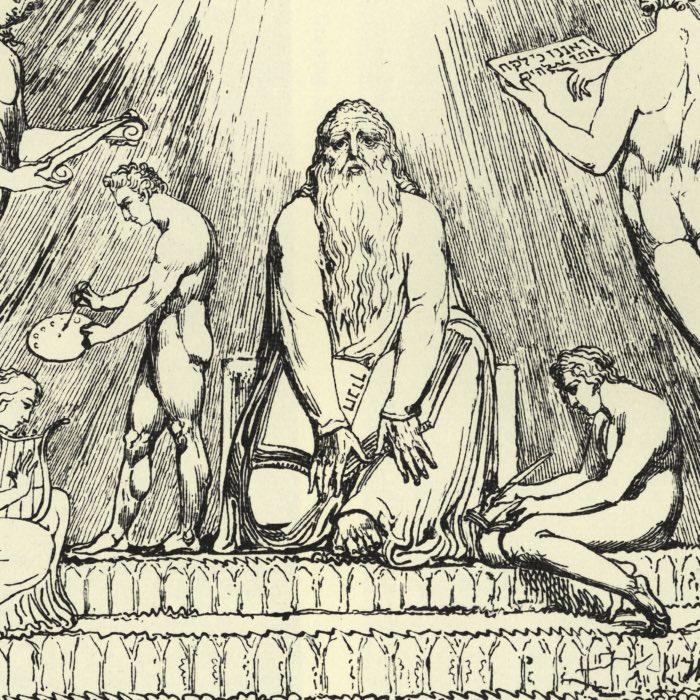

On a spiritual level, the concept of angels and analogous beings across religious traditions reflects humanity’s shared desire to connect with the divine, seek protection, and receive guidance. Emerging from the ancient Near East, the angelic tradition evolved through layers of cultural interaction, from Zoroastrian, Jewish and Hellenistic thought to Christian and Islamic adaptations. In Buddhist and Asian traditions, celestial beings such as devas and Bodhisattvas fulfill similar roles, enriched by local cosmologies and cultural exchanges.

The influence of Hellenistic culture, particularly through Gandharan art (see also this post), demonstrates the dynamic interplay of religious ideas across regions and epochs. By exploring such mythologies, we gain a better understanding of the fluidity – and potentially also universality – of cultural and spiritual concepts that have shaped human beliefs and practices for millennia.

References and further reading

- Thomas Schumacher, Engel in Bibel, Geschichte und Theologie, 2022, Pneuma Verlag, ISBN: 978-3942013581

- Heinrich Schmidt, Margarethe Schmidt, Die vergessene Bildersprache christlicher Kunst: Ein Führer zum Verständnis der Tier-, Engel- und Mariensymbolik, 2018, C.H.Beck, ISBN: 978-3406718298

- Eckhard Bieger, Das Bilderlexikon der christlichen Symbole, 2016, Benno, ISBN: 9783746246536

- Collins, J. J., The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature, 1999, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802843715

- Esposito, John, What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam, 2002, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-19-515713-0

- Kurt A. Behrendt, The art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum Of Art, 2007, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300120271

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

- Kurt A. Behrendt, How To Read Buddhist Art, 2019, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 978-1588396730

- Gabriele Seitz, Die Bildsprache des Buddhismus, 2006, Patmos-Verl, ISBN: 9783491724860

- Wikipedia article on Angels in Artꜛ

comments