St. George the dragon-slayer: A comparative perspective on dragons in the East and West

The figure of St. George, often depicted as a dragon-slaying saint, occupies a central place in Christian hagiography and European folklore. Revered as a martyr, warrior, and protector, St. George symbolizes the triumph of good over evil and has been embraced as a patron saint by numerous cultures and nations. His legend, especially the iconic tale of slaying a dragon, resonates deeply within Western traditions. However, the symbolism of dragons in the East, particularly in Asia, provides a striking contrast, offering a lens through which to explore cultural divergences in the interpretation of mythical creatures.

Miniature from a 13th-century Passio Sancti Georgii, Verona, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Miniature from a 13th-century Passio Sancti Georgii, Verona, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

St. George: Historical origins and early veneration

The historical St. George remains an enigmatic figure, his life obscured by the passage of centuries and the layers of myth that have enveloped his memory. According to early traditions, St. George was born in the late 3rd century CE, in Cappadocia (modern-day central Turkey), a region known for its vibrant Greco-Roman culture and early Christian communities. This period marked the zenith of Roman imperial power but also an era of increasing tension between the pagan establishment and the growing Christian movement.

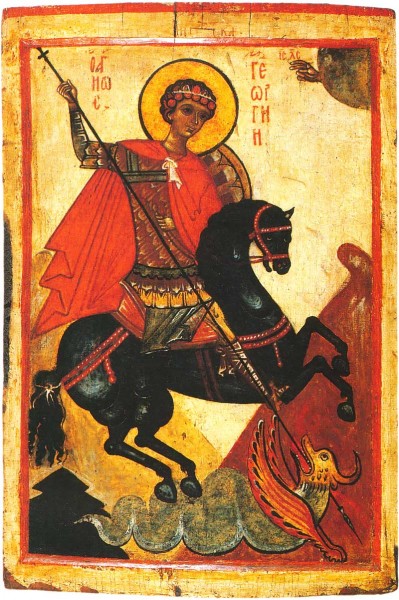

Byzantine icon of George, Athens, Greece. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Historical context: The Roman Empire and Christian persecution

St. George’s life unfolded during the reign of Emperor Diocletian, whose policies towards Christians were shaped by his vision of restoring traditional Roman religious practices as a unifying force for the empire. In 303 CE, Diocletian issued a series of edicts mandating the persecution of Christians, targeting their leaders, sacred texts, and places of worship. This campaign, later known as the “Great Persecution”, sought to suppress the burgeoning faith that the Roman authorities viewed as subversive to imperial unity.

St. George is traditionally described as a Roman soldier, likely of Greek descent, who served in the imperial guard. As a member of the military, he would have been subject to strict expectations of loyalty to the emperor and the official Roman gods. However, St. George’s Christian faith placed him in direct conflict with these obligations. His defiance of imperial decrees, particularly his refusal to participate in pagan rites or renounce his beliefs, led to his arrest and eventual martyrdom.

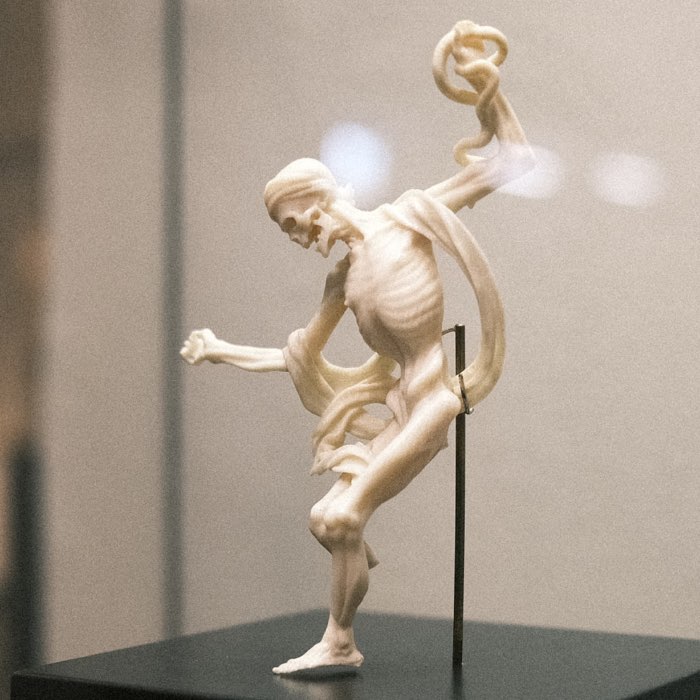

The martyrdom of St. George

The details of St. George’s martyrdom, though largely apocryphal, have been a focal point of his veneration. Early accounts, such as those found in the Passio Sancti Georgii (Passion of St. George), depict him as enduring prolonged torture before being executed. Common elements include his scourging, the use of a wheel of swords to inflict excruciating pain, and his steadfast faith throughout his ordeal. These narratives emphasize his role as a witness (martys) to the Christian faith, embodying the ideals of courage, endurance, and spiritual fidelity.

George being wheeled, Michiel Coxcie, 1580s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

George being wheeled, Michiel Coxcie, 1580s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Early veneration and the spread of the cult

St. George’s veneration began soon after his death, initially among local Christian communities in the Eastern Roman Empire. His status as a soldier and martyr resonated particularly with those facing persecution, making him a powerful symbol of divine protection and the triumph of faith over adversity. Churches and shrines dedicated to St. George appeared in Cappadocia and the surrounding regions, often incorporating earlier pagan sites, which facilitated the transition to Christian worship.

By the 5th century CE, St. George’s cult had gained widespread popularity in the Byzantine Empire, where he was honored as one of the great “soldier saints” alongside figures like St. Demetrius and St. Theodore. The Eastern Church revered him as a defender of Christians and a model of military virtue sanctified by faith.

Western expansion of the cult

The spread of St. George’s veneration to Western Europe occurred gradually, facilitated by the mobility of pilgrims, merchants, and soldiers. During the Crusades (11th–13th centuries), returning knights and chroniclers brought tales of St. George’s miraculous intercessions, further embedding his legend into medieval Christianity. He became a symbol of chivalry, blending the ideals of martial prowess and religious devotion.

The official recognition of St. George as the patron saint of England by King Edward III in the 14th century marked the zenith of his popularity in Western Europe. The Order of the Garter, England’s highest order of chivalry, adopted St. George as its patron, solidifying his association with knighthood and the defense of Christendom.

Iconography and global legacy

St. George’s portrayal in art and iconography reflects the evolution of his legend. Early depictions in Byzantine mosaics emphasize his role as a martyr, often showing him in military attire with a cross. By the Middle Ages, Western art increasingly focused on the dragon-slaying motif, aligning with the chivalric and allegorical themes that resonated with European audiences.

Saint George and the Dragon, Bernat Martorell, 1434/35. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Saint George and the Dragon, Bernat Martorell, 1434/35. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

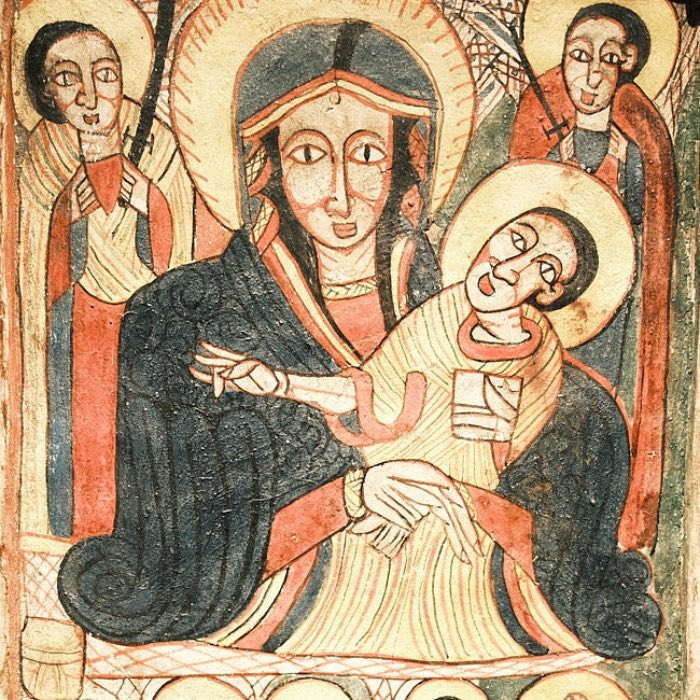

Today, St. George’s influence transcends geographic and cultural boundaries. He is celebrated not only in Christian traditions but also in the folklore and national identities of countries as diverse as Georgia, Ethiopia, and Russia. This widespread veneration highlights his enduring legacy as a figure who embodies the universal human aspiration for courage, faith, and the triumph of good over evil.

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes, Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes, Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes, Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes, Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes, Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes, Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes (detail), Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes (detail), Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes (detail), Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George’s Fight with the Dragon Vita icon with twelve scenes (detail), Russia, 19th century, Egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel, Russia, before 1900, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel, Russia, before 1900, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel (detail), Russia, before 1900, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel (detail), Russia, before 1900, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel (detail), Russia, before 1900, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel (detail), Russia, before 1900, egg tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George as Dragon Killer, Russia, 19th century Metal, enamel, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George as Dragon Killer, Russia, 19th century Metal, enamel, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, Russia, 18th/ 19th century, metal, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. George Fighting the Dragon, Russia, 18th/ 19th century, metal, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The legend of St. George and the dragon

The tale of St. George and the dragon, central to his mythos, emerged in the Middle Ages and became a defining element of his iconography. The most famous version of the story is found in Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend (Legenda Aurea, 13th century), a compilation of saints’ lives that popularized hagiographical traditions across Europe.

Miniature of George and the Dragon, ms. of the Legenda Aurea, dated 1348. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Miniature of George and the Dragon, ms. of the Legenda Aurea, dated 1348. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The legend describes a city plagued by a dragon that demands human sacrifices. When the king’s daughter is chosen as the next victim, St. George intervenes. He confronts and slays the dragon, saving the princess and the city. The grateful citizens convert to Christianity, symbolizing the triumph of faith over evil and chaos.

The dragon in this legend represents more than a physical threat; it is a metaphor for the forces of sin, paganism, and spiritual danger. St. George’s victory over the dragon symbolizes the power of Christian virtue and divine intervention to overcome evil. This narrative resonated deeply in medieval Europe, aligning with the chivalric ideals of courage, piety, and the defense of the weak.

Russian icon, mid 14th century, Novgorod. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The dragon-slaying motif contributed to St. George’s adoption as a patron saint in various regions, including England, Georgia, and Ethiopia. Each culture incorporated local elements into the legend, enhancing its universal appeal while grounding it in regional traditions.

St. George and cross-cultural influence

The story of St. George and the dragon has parallels in other cultural traditions, highlighting the universal appeal of the hero’s triumph over a monstrous adversary. Myths of dragon-slaying or serpent-conquering heroes appear in ancient Mesopotamian, Indian, and Greek narratives, suggesting a shared archetypal theme.

Comparative narratives include:

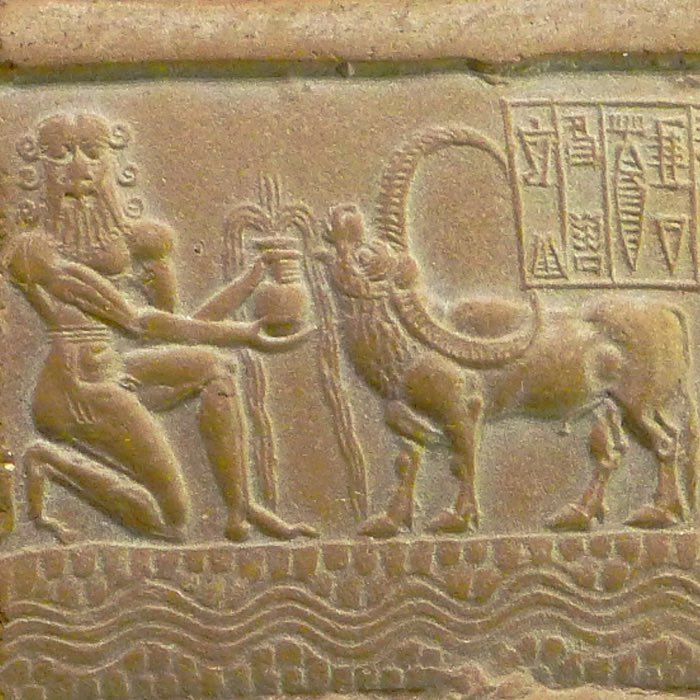

- In Mesopotamian mythology, Marduk slays the chaos dragon Tiamat to establish cosmic order.

- In Hindu mythology, Indra defeats the serpent Vritra, releasing the waters and restoring life.

- In Greek mythology, Perseus slays the sea monster to save Andromeda, a tale that closely resembles the St. George legend.

These parallels indicate a shared human fascination with the hero’s battle against chaos, adapted to fit the moral and spiritual frameworks of different cultures.

The spread of Christianity and the incorporation of local traditions into its narratives may have influenced the development of the St. George legend. The hero’s triumph over the dragon became a powerful metaphor for the Christian mission to overcome paganism and sin, integrating earlier mythological motifs into a distinctly Christian context.

Dragons in Western and Asian traditions: A comparative perspective

The contrasting symbolism of dragons in Western and Asian traditions offers insights into differing cultural worldviews. While Western dragons are often depicted as malevolent creatures to be vanquished, Asian dragons are typically associated with power, wisdom, and harmony.

Western dragons: Chaos and evil

In Western mythology, dragons are frequently portrayed as dangerous, destructive beings. They embody chaos, greed, and the untamed forces of nature. Stories such as Beowulf’s battle with a treasure-hoarding dragon and the tale of St. George reflect the Western tendency to depict dragons as adversaries to be conquered.

15th-century manuscript illustration of the battle of the Red and White Dragons from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

This perspective is rooted in Christian theology, where dragons are linked to Satan and the apocalyptic imagery of Revelation. The slaying of dragons in Western legends often symbolizes the victory of divine order over chaos and sin, reinforcing the moral and spiritual dualities central to Christian thought.

St. George fighting the dragon, Paolo Uccello, around 1470. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

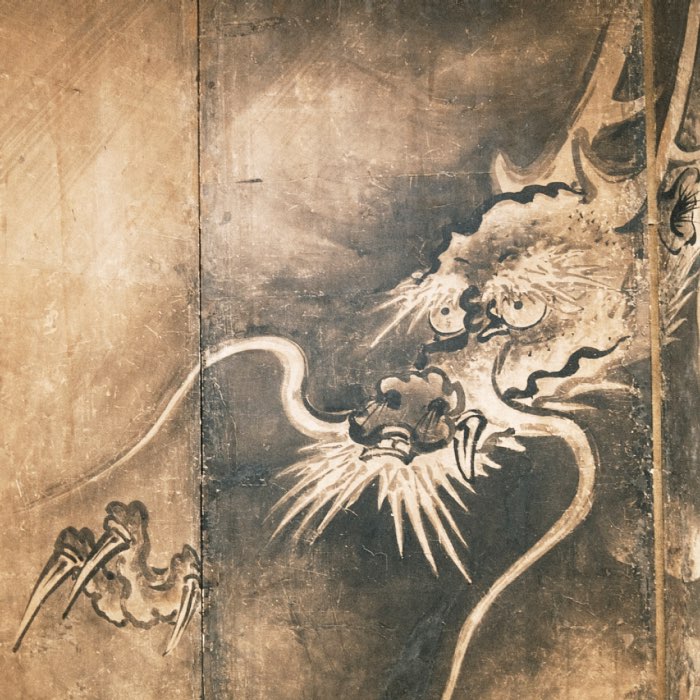

Asian dragons: Guardians and symbols of harmony

In stark contrast to their Western counterparts, dragons in Asian traditions are revered as benevolent and auspicious creatures. Far from being adversaries, they are seen as embodiments of cosmic forces, protectors, and bringers of fortune. Their enduring significance in mythology, religion, and art underscores their deep integration into the spiritual and cultural frameworks of Asia.

Matsuri Yatai Dragon, Hokusai, 1844, Japan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

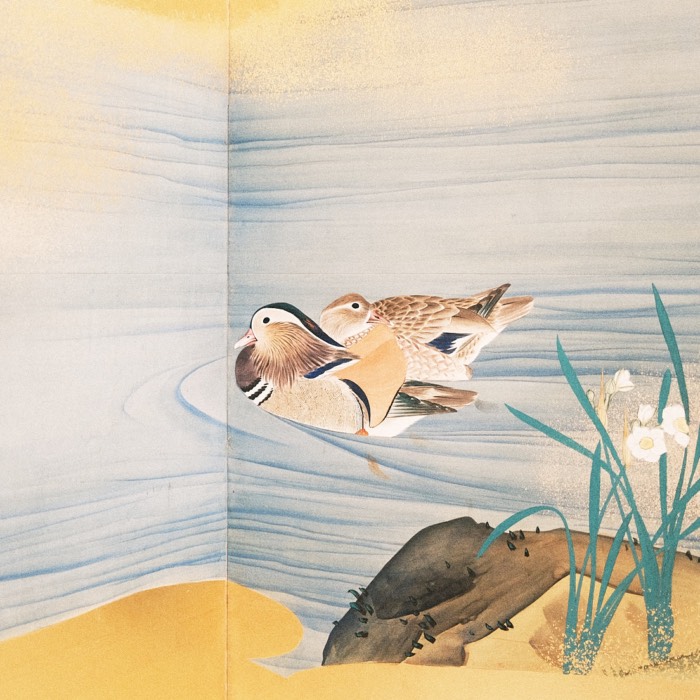

Symbolism in Chinese mythology

Chinese dragons (lóng, 龙) are among the most revered symbols in Chinese culture, representing strength, wisdom, and the life-giving forces of water. They are associated with rain, rivers, and the seas — key elements in sustaining agricultural life. As masters of weather and water, they were believed to bring rain to parched lands, ensuring prosperity and harmony.

The Nine Dragon Wall in the Beihai Park, a large imperial garden in central Beijing. In China, dragons are associated with power, strength, and good fortune. The emperor used the dragon as a symbol of his imperial power along with the phoenix, which was considered the queen of birds und thus symbolized the empress. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In China, dragons embody the harmonious interplay between heaven, earth, and humanity. They are often depicted holding a pearl, symbolizing spiritual energy or cosmic wisdom. The Chinese emperor was traditionally regarded as the “Son of the Dragon”, and dragon motifs adorned imperial robes, palaces, and artifacts as a sign of divine right and power.

The Chinese New Year dragon dance, performed to drive away evil spirits and usher in good fortune, reflects the creature’s protective and auspicious qualities. Dragon boat races, held during the Dragon Boat Festival, honor dragons as water guardians while commemorating historical events.

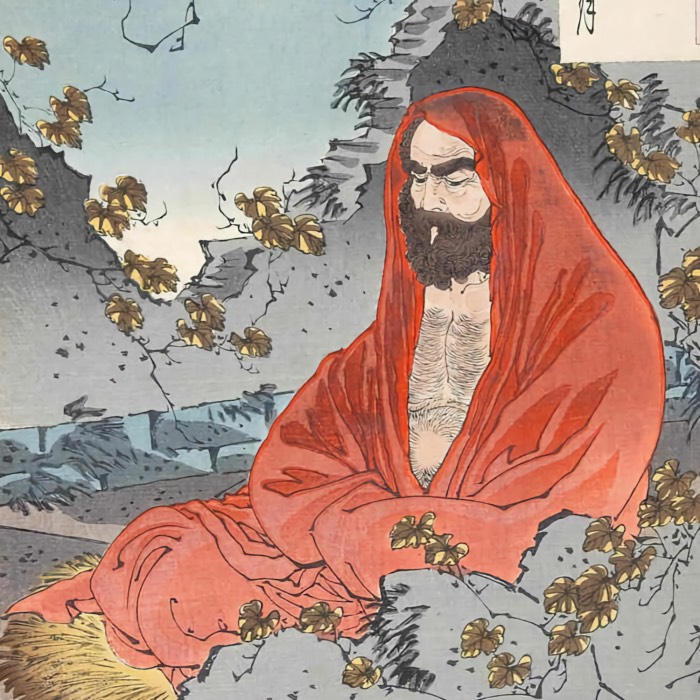

Japanese dragons: Protectors and spiritual beings

Japanese dragons (ryū, 龍) share many attributes with their Chinese counterparts but are often depicted as more serpentine and associated with specific deities or locales. They are guardians of sacred places, treasures, and knowledge, often linked to Shinto and Buddhist traditions.

Detail of a large dragon painting at the ceiling of a hall of Kennin-ji, Kyoto, Japan. Source: Emmett Anderson flickrꜛ (license: CC BY 2.0)

Japanese dragons are believed to inhabit bodies of water such as lakes and rivers, guarding temples and shrines. For instance, Ryūjin, the dragon god of the sea, is a central figure in Japanese mythology, credited with controlling tides and bestowing gifts like the legendary tide jewels (kanju and manju), which symbolize abundance and order.

The dragon’s protective role extends to Buddhist temples, where they are often depicted in art as guardians of the Buddha’s teachings. Their presence symbolizes enlightenment and the suppression of ignorance and evil forces.

Nāgas in Hinduism and Buddhism

In South and Southeast Asia, dragons often take the form of nāgas—serpentine beings revered as semi-divine protectors and mediators between the earthly and spiritual realms.

Crowned golden nāga-woodcarving at Keraton Yogyakarta, Java. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 2.0)

Nāgas are central to Hindu cosmology, representing fertility, prosperity, and water. They are often depicted guarding treasures or sacred rivers. Vasuki, the king of nāgas, plays a prominent role in the churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan) to obtain the nectar of immortality.

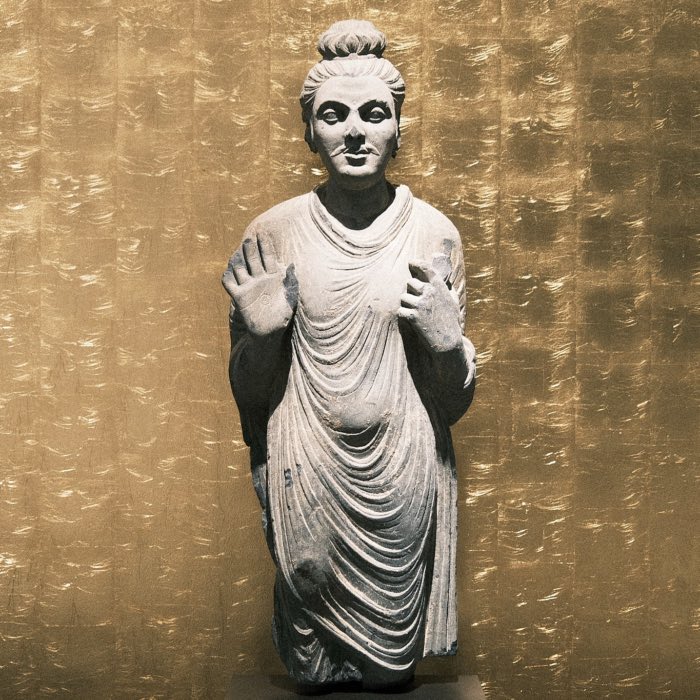

Nāgas in Buddhist traditions are spiritual beings who protect the Dharma (Buddhist teachings). The story of Mucalinda, the nāga who shielded the meditating Buddha from a storm by coiling around him and spreading its hood as a canopy, exemplifies their role as protectors and benevolent forces.

Shared attributes across cultures

Despite regional variations, Asian dragons share certain unifying characteristics:

- Wisdom and longevity: Dragons are often depicted as wise, ancient beings, embodying patience and profound knowledge. They are associated with immortality and the eternal cycles of nature.

- Harmony and balance: Asian dragons are integral to cosmological systems that emphasize the unity and balance of opposing forces. For example, in Chinese philosophy, they often represent the yang (active, masculine) energy in harmony with the phoenix, symbolizing yin (passive, feminine) energy.

- Spiritual connection to nature: Whether as rainmakers, river deities, or temple guardians, Asian dragons symbolize humanity’s connection to and dependence on nature. They are both protectors and reminders of the need to live in harmony with the natural world.

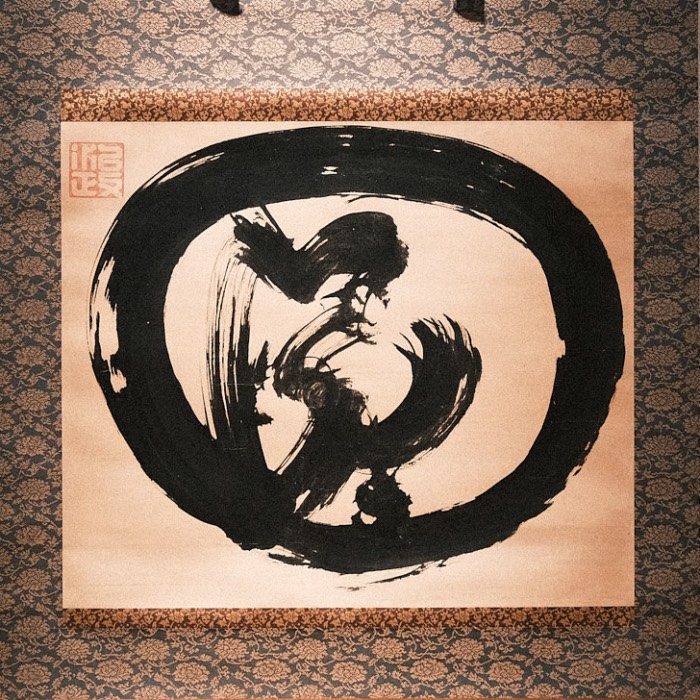

Artistic and literary depictions

Dragons appear prominently in Asian art, literature, and architecture:

- In Chinese and Japanese art, dragons are depicted with flowing, sinuous bodies, symbolizing their ability to traverse land, sea, and sky. Their dynamic forms embody fluidity and adaptability.

- Ancient texts, such as the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shan Hai Jing) in Chinese mythology, describe dragons as celestial creatures that dwell in heavenly realms or underwater palaces.

- In Japanese woodblock prints and Buddhist murals, dragons often coil around mountains or temples, emphasizing their protective role.

A dragon from the Nine Dragons Scroll by Chen Rongꜛ, 1244 CE, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Dragon art on a vase, Yuan dynasty, China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Contrasts and complementarity with Western dragons

The benevolent and integrative symbolism of Asian dragons highlights the stark contrast with Western traditions, where dragons often signify chaos and evil. However, these divergent interpretations reflect the distinct worldviews of the two cultures:

- Western focus on duality: Western mythology often frames dragons as obstacles to be overcome in a narrative of moral or spiritual struggle.

- Asian emphasis on harmony: Asian traditions incorporate dragons into a cosmological framework, viewing them as essential components of a balanced universe rather than adversarial forces.

Conclusion

The mythology of St. George and his battle with the dragon is rich in historical, cultural, and theological elements. It encapsulates the medieval Christian ideals of heroism and faith while drawing on timeless archetypal themes of the hero’s struggle against chaos. The contrasting depictions of dragons in Western and Asian traditions underscore the diverse ways in which cultures interpret and symbolize the forces of nature and morality, encouraging us to broaden our perspectives and view the world through different lenses.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on St. Georgeꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Mythology of Dragonsꜛ

- Wikipeida article on Japanese Dragonsꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Chinese Dragon Boat Festivalꜛ

- Wikiwand article on the Classic of Mountains and Seasꜛ

- Dalrymple, W., From the Holy Mountain: A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East, 1997, Henry Holt Company

- Loomis, C. Grant, White Magic: An Interpretation of English Folklore, 2010, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN: 978-1164494010

- West, M. L., The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, 1999, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198152217

comments