The three Magi: Unraveling their history and symbolism

The image of the three kings visiting the infant Jesus is one of the most iconic scenes of the Nativity story. However, the biblical account in the Gospel of Matthew neither mentions “kings” nor specifies their number. Instead, it speaks of “Magi” from the East, learned astrologers or scholars who followed a star to honor the newborn Jesus. Let us explore the historical and cultural roots of these Magi and clarify some common misconceptions about their identity.

The three Magi, Byzantine mosaic, c. 565, Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy, restored during the 19th century. As here, Byzantine art usually depicts the Magi in Persian clothing, which includes breeches, capes, and Phrygian caps. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5).

The three Magi, Byzantine mosaic, c. 565, Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy, restored during the 19th century. As here, Byzantine art usually depicts the Magi in Persian clothing, which includes breeches, capes, and Phrygian caps. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5).

Account of the Magi in the New Testament

The Gospel of Matthew (2:1–12) introduces the Magi as “wise men from the East”. These figures are described as astrologers or scholars who interpreted celestial signs to predict significant events. They traveled to Jerusalem to inquire about the “king of the Jews” after observing a star they associated with his birth. Guided by this star, they eventually reached Bethlehem, where they presented symbolic gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to Jesus.

Notably, the text does not

- specify their number,

- call them “kings”, and

- provide details about their names, appearance, or mode of travel.

The association of three Magi likely arose from the three gifts mentioned, while their portrayal as “kings” was a later theological and symbolic interpretation designed to align with Old Testament prophecies.

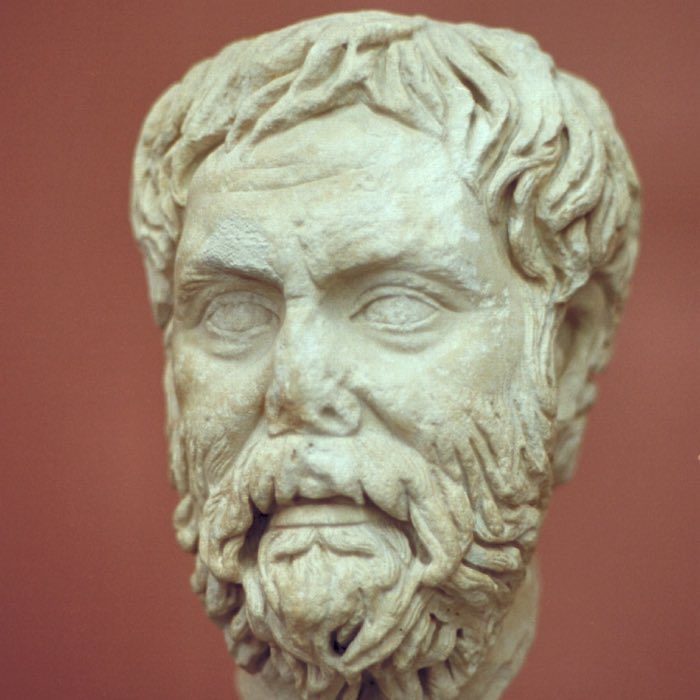

The Magi in Zoroastrianism

The term Magi (Greek: Μάγοι) originates from the Old Persian word maguš, referring to members of a priestly caste in the Zoroastrian religion. Zoroastrianism, founded by the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra) in ancient Persia, was the dominant religion in the region for centuries.

Zoroastrian priests (Magi) carrying barsoms. A barsom is a ritual implement used by Zoroastrian priests to solemnize certain sacred ceremonies. Gold statuettes from the Oxus Treasure of the Achaemenid Empire, 4th century BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0).

In Zoroastrianism, the Magi were not just religious leaders but also scholars and astronomers. They studied the stars and planets, believing celestial movements reflected divine will. This dual role as priests and astrologers aligns with the Gospel’s depiction of the Magi as interpreters of the “star of Bethlehem”.

Zoroastrian Magus carrying barsom. Chopped gold piece. Statuettes from the Oxus Treasure of the Achaemenid Empire, 4th century BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5).

Zoroastrianism emphasized dualism, the cosmic struggle between good (Ahura Mazda) and evil (Angra Mainyu). Central to its teachings was the idea of a savior figure, the Saoshyant, who would bring ultimate salvation. Some scholars suggest the Magi’s journey to honor Jesus may have been influenced by their Zoroastrian expectations of a savior.

Misconceptions: “Kings” and their number

The transformation of the Magi into “kings” and the fixation on their number are later developments in Christian tradition, reflecting theological and symbolic interpretations rather than historical accuracy.

From Magi to “kings”

The depiction of the Magi as kings arose in the early centuries of Christianity. Theologians like Tertullian (3rd century CE) interpreted them as fulfilling Old Testament prophecies, such as Psalm 72:10–11, which describes kings bringing gifts to the Messiah. This theological link reshaped the Magi’s image, emphasizing their royal status and symbolic representation of Gentile nations.

The number three

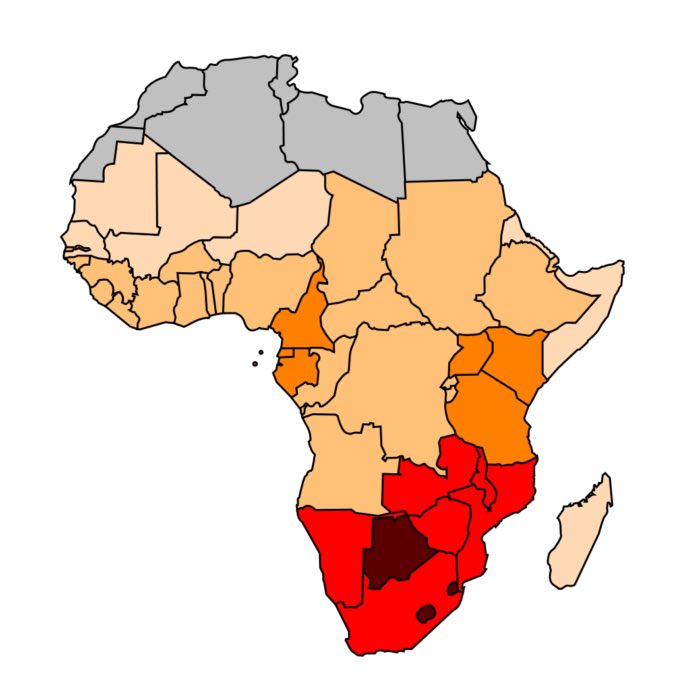

The Bible does not specify how many Magi visited Jesus. Early Christian art and writings show various numbers — ranging from two to twelve. The tradition of “three kings” became dominant in the Western Church during the Middle Ages, symbolizing the three gifts and possibly representing the three known continents of the time: Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Names and legends

The Magi were not named in the Gospel of Matthew, where they are first mentioned. However, by the 6th century, traditions had assigned them names and attributes, which became widely recognized in Christian lore:

- Caspar (or Gaspar): Often depicted as an older man with a white beard, offering frankincense.

- Melchior: Portrayed as middle-aged, bringing gold.

- Balthasar: Shown as a young man of African descent, presenting myrrh.

The names of the Magi appear in an apocryphal text called the Excerpta Latina Barbari, a Latin manuscript dating to the 6th century. This work drew on earlier Greek and Eastern traditions but adapted the figures for a Western audience. The names Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar are derived from earlier Syriac and Persian sources, where the Magi were sometimes referred to by different names and characteristics. Over time, these names were canonized in Western Christian tradition and became central to the story of the Nativity.

The names and descriptions of the Magi evolved to emphasize the universality of Christ’s message:

- Three ages of man: The Magi represent youth (Balthasar), maturity (Melchior), and old age (Caspar), symbolizing the stages of human life.

- Diverse ethnicities: By the late medieval period, the Magi were depicted as representing different parts of the known world: Europe (Melchior), Asia (Caspar), and Africa (Balthasar). This diversity highlighted the idea that Christ’s salvation was for all nations and peoples, aligning with the prophecy in Isaiah 60:3: “Nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn.”

- Gifts and symbolism: The gifts they brought were associated with their respective identities and the roles they played in the Nativity narrative:

- Gold: A gift fit for a king, symbolizing Jesus’ royalty.

- Frankincense: Used in worship, representing Jesus’ divinity.

- Myrrh: A burial spice, foreshadowing Jesus’ suffering and death.

While these interpretations are theological, they underscore the layered significance attributed to the Magi’s visit.

The Three Wise Kings, Catalan Atlas, 1375, fol. V: “This province is called Tarshish, from which came the Three Wise Kings, and they came to Bethlehem in Judaea with their gifts and worshipped Jesus Christ, and they are entombed in the city of Cologne two days journey from Bruges”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Three Wise Kings, Catalan Atlas, 1375, fol. V: “This province is called Tarshish, from which came the Three Wise Kings, and they came to Bethlehem in Judaea with their gifts and worshipped Jesus Christ, and they are entombed in the city of Cologne two days journey from Bruges”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Historical and cultural context

The journey of the Magi reflects the historical trade routes and cultural exchanges that characterized the ancient world. Babylonian and Persian astronomers were renowned for their expertise in celestial observation, astrology, and interpreting omens, making them natural candidates for the “wise men” described in the Gospel of Matthew. The East, particularly regions like Babylon and Persia, was a wellspring of advanced scientific and philosophical thought, and the idea of learned men traveling from these areas to the Roman province of Judea aligns with documented interactions between these cultures.

Incised sarcophagus slab with the Adoration of the Magi from the Catacombs of Rome, 3rd century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: The copyright holder, Giovanni Dall’Orto, allows anyone to use it for any purpose, provided that the copyright holder is properly attributed. Redistribution, derivative work, commercial use, and all other use is permitted.).

The Magi likely traveled along established trade routes such as the Silk Road or the Royal Road of the Achaemenid Empire, which facilitated not only commerce but also the exchange of ideas, religions, and cultural practices. These routes connected the Eastern empires with the Mediterranean world, enabling figures like the Magi to carry gifts and knowledge across great distances.

The Magi Journeying, James Tissot, c. 1890, Brooklyn Museum, New York City. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Magi Journeying, James Tissot, c. 1890, Brooklyn Museum, New York City. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Symbolism in the narrative

The Magi’s journey symbolizes more than just physical travel; it represents a crossing of cultural and spiritual boundaries. Their homage to Jesus reflects the universal appeal of his message, transcending the confines of Judaism to include Gentiles and peoples of all nations. This stands in stark contrast to the reaction of King Herod, whose fear and hostility highlight the worldly concerns of power and political stability.

The Magi, guided by the star, embody a peaceful quest for divine truth, while Herod represents the darker forces of earthly ambition and insecurity. This juxtaposition underscores the universal and inclusive nature of Jesus’ mission, which invites even those outside the Jewish tradition to recognize his significance.

The blending of cultures

The story of the Magi also illustrates the blending of Eastern and Western traditions. In Persian culture, the magi were Zoroastrian priests skilled in interpreting celestial signs, suggesting that the Gospel writer incorporated elements from Eastern religious practices into the narrative. This cultural interweaving reflects the cosmopolitan nature of the Roman Empire, where religious and philosophical ideas were shared, adapted, and transformed across diverse populations.

Influence of Eastern traditions and Western adaptations

The story of the Magi originates in Eastern Christian traditions, where early Syriac and Persian texts described them as wise men or astrologers, possibly linked to Zoroastrian priesthoods. These accounts emphasized their expertise in interpreting celestial phenomena, aligning with their role in the Gospel as seekers of divine revelation through the “star of Bethlehem”. In these traditions, the Magi symbolize the wisdom of the East recognizing the truth of Christ.

Adoration of the Magi, Giotto di Bondone, 1302. The Star of Bethlehem is shown as a comet above the child. Giotto witnessed an appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1301. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Adoration of the Magi, Giotto di Bondone, 1302. The Star of Bethlehem is shown as a comet above the child. Giotto witnessed an appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1301. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

As the story spread westward, it was adapted and expanded by Western Christian traditions. By the 6th century, the names Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar were added to the Magi’s story, and their characteristics were detailed to reflect theological symbolism. Medieval works such as John of Hildesheim’s Historia Trium Regum (History of the Three Kings) further enriched their narrative, adding fictionalized accounts of their journey, their royal status, and the mystical significance of their gifts.

Adoration of the Magi, capital, exhibited in the chapter house of Saint-Lazare d’Autun Cathedral, 12th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0).

Adoration of the Magi, capital, exhibited in the chapter house of Saint-Lazare d’Autun Cathedral, 12th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0).

The Western tradition solidified their identity as kings, aligning their story with Old Testament prophecies like Psalm 72:10–11 (“May the kings of Tarshish and of distant shores bring tribute to him.”). These theological interpretations made the Magi representatives of the Gentile world acknowledging Christ as King.

Sketch of the medieval shrine of the Magi, Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral. The Shrine of the Three Kings is a magnificent reliquary believed to contain the bones of the Magi. These relics were said to have been brought from Milan to Cologne in 1164 by Archbishop Rainald of Dassel, establishing Cologne as a major pilgrimage site.

Sketch of the medieval shrine of the Magi, Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral. The Shrine of the Three Kings is a magnificent reliquary believed to contain the bones of the Magi. These relics were said to have been brought from Milan to Cologne in 1164 by Archbishop Rainald of Dassel, establishing Cologne as a major pilgrimage site.

Celebrations of the Magi: Epiphany and Christmas

In Western Christianity, the Magi became central to Epiphany celebrations (feast day commemorating the visit of the Magi), observed on January 6. Epiphany commemorates the manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles, as symbolized by the Magi’s homage. Over time, their story was integrated into Christmas traditions, celebrated on December 25 or the evening of December 24. Artistic depictions, hymns, and rituals elevated the Magi as pivotal figures in the broader Nativity narrative.

The Adoration of the Magi, Edward Burne-Jones, 1894. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Adoration of the Magi, Edward Burne-Jones, 1894. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

In contrast, many Eastern Orthodox Churches maintain a distinct focus on January 6, the feast of Theophany (Epiphany), as the primary celebration of Christ’s birth and revelation. This day often includes commemorations of the Magi, with their story reflecting their Zoroastrian heritage as astrologers and scholars. The difference in dates between Eastern and Western traditions highlights variations in liturgical calendars and theological emphasis.

Conclusion

The story of the Magi, while legendary, carries profound symbolic meaning. Rooted in Zoroastrian traditions, it reflects the Magi’s dual role as scholars and spiritual seekers. Their journey to honor the newborn Jesus illustrates the rich cultural and religious exchanges of the ancient world and the theological message of universal salvation.

As their story was adapted and enriched over centuries, the Magi came to symbolize the recognition of Christ’s divinity. By exploring the historical and cultural origins of this legend, we gain insight into how early Christians creatively wove diverse traditions into a narrative that constitutes the foundation of Christian belief and practice.

References and further reading

- Albert de Jong, Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature, 1998, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN: 978-9004108448

- R.C. Zaehner, The Teachings of the Magi: A Compendium of Zoroastrian Beliefs, 2001, Routledge; 1st Edition, ISBN: 978-1032148540

- Sarah Stewart, Alan Williams, and Almut Hintze, The Zoroastrian Flame: Exploring Religion, History and Tradition, 2016, I.B. Tauris, ISBN: 978-1784536336

- Peter Clark, Zoroastrianism: An Introduction to an Ancient Faith, 1998, Liverpool University Press, ISBN: 978-1898723783

- Jenny Rose, The Image of Zoroaster: The Persian Mage Through European Eyes, 2000, Bibliotheca Persica, ISBN: 978-0933273450

- Wikipedia article on the three Magiꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Adoration of The Magiꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Excerpta Latina Barbariꜛ

comments