Anno Domini: Tracing the history of the Christian calendar

The dating system widely used today, referred to as the “Anno Domini” (CE) system, marks time based on the birth of Jesus Christ. However, historical and astronomical evidence suggests that Jesus was likely born several years before the start of Year 1 CE. This discrepancy arises from miscalculations by medieval scholars and sheds light on the challenges of reconstructing historical timelines. Additionally, a fringe theory posits that a significant portion of the Middle Ages was fabricated, casting further intrigue into the construction of historical timekeeping.

Anno Domini 1583 inscription at Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England, UK. Image credit: Leo Reynolds on flickrꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Anno Domini 1583 inscription at Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England, UK. Image credit: Leo Reynolds on flickrꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The origin of Anno Domini

The “Anno Domini” (CE) system, marking years as “the year of our Lord”, was introduced in the 6th century by Dionysius Exiguus, a Scythian monk and theologian. It aimed to provide a Christian framework for dating historical events, replacing the earlier Diocletian calendar, which counted years from the accession of the Roman Emperor Diocletian (284 CE), infamous for his persecution of Christians.

Dionysius Exiguus. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Pre-Dionysian year counting systems in the Roman Empire

Before Dionysius’ innovation, the Roman world employed various dating systems. The most common was the AUC (Ab Urbe Condita) system, counting years from the legendary founding of Rome in 753 BCE. Additionally, emperors often dated events and official documents by their regnal years or significant imperial milestones. For instance:

- Regnal years: Events were dated as occurring in the nth year of a reigning emperor.

- Consular years: Years were identified by the names of the two consuls elected annually.

- Era of the Diocletian calendar: Introduced in 284 CE, this system marked years from the beginning of Diocletian’s reign and was widely used in administrative and ecclesiastical contexts. However, as Christianity gained dominance, many leaders found it inappropriate to honor a persecutor of Christians in official chronology.

Dionysius’ aim was to establish a Christian calendar that symbolically replaced the Diocletian era with one centered on the incarnation of Christ, thereby reorienting time itself around Christian theology.

How Dionysius calculated the year 1 CE

Dionysius’ calculation of the birth year of Jesus was based on the best historical and theological sources available to him at the time. These included:

- Biblical texts: Dionysius likely relied on interpretations of the Gospel accounts, particularly references to King Herod and Roman governance under Quirinius.

- Historical records: He consulted Roman and ecclesiastical histories, including Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History (4th century) and the works of earlier Christian chronographers.

- Astronomical cycles: Dionysius was tasked with determining the correct date for Easter, which involved detailed calculations of lunar cycles and historical datings of significant Christian events. His calculation of Christ’s birth year emerged from these computations as an incidental yet influential result.

The rise of the Anno Domini system

Dionysius initially designed the CE system for ecclesiastical purposes, particularly for calculating the date of Easter. Its adoption was slow but steady, gaining traction primarily in the Western Christian Church:

- The Venerable Bede (8th century): The Anglo-Saxon historian and theologian popularized the CE system in his seminal work, Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede’s influence extended across Europe, promoting the use of CE in historical and religious contexts.

- Carolingian Empire (9th century): Under Charlemagne, the CE system was formalized as the standard for official documents and record-keeping, aligning with efforts to unify Christendom.

By the late medieval period, the CE system became ubiquitous in European Christian societies, replacing local systems and establishing itself as a key marker of Western historical identity.

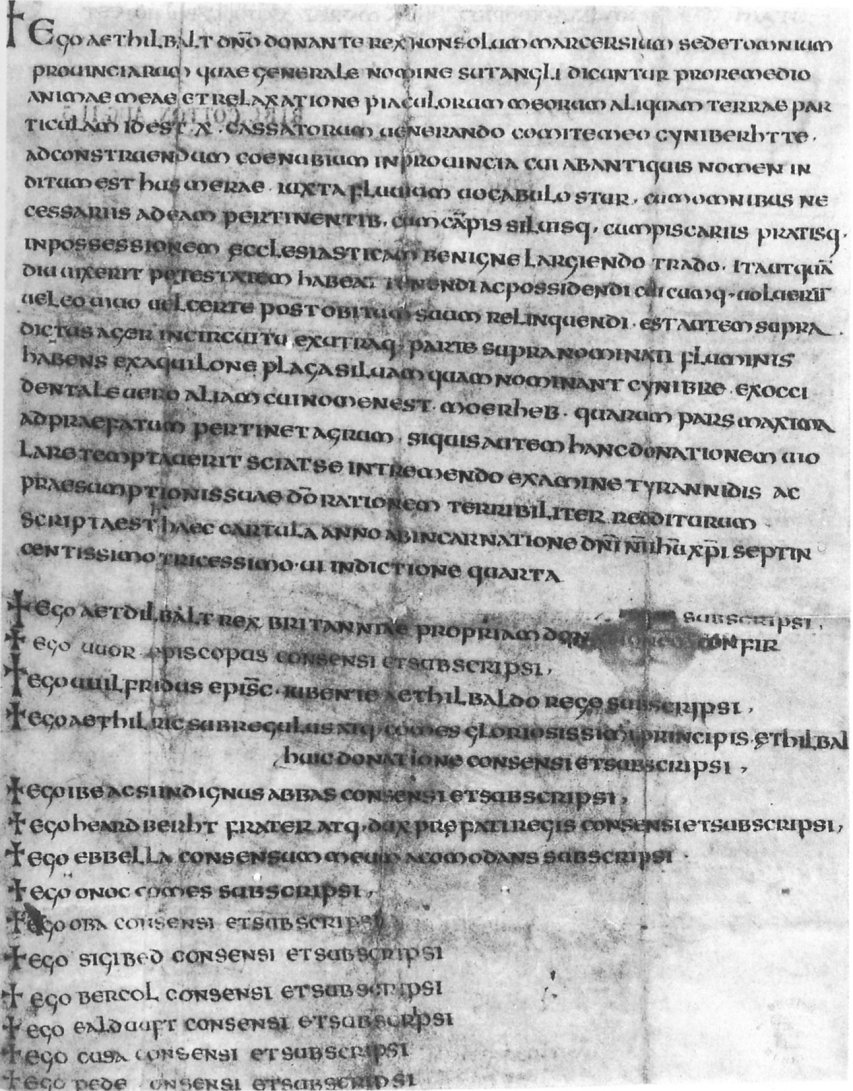

The charter of Æthelbald of Mercia from the year 736 is one of the first documents dated according to the year of incarnation of Jesus Christ (Anno Domini). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical inaccuracies and debates

While Dionysius’ Christian-centered calendar has been accepted for centuries, historical and astronomical evidence indicates that its starting point, Jesus’ birth, was likely earlier than the designated Year 1 CE. Several factors contribute to this discrepancy:

The death of King Herod

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for Jesus’ earlier birth comes from the Gospel of Matthew, which states that Jesus was born during the reign of King Herod the Great. Historical records, including those of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, indicate that Herod died in 4 BCE. This would place Jesus’ birth before that year, likely between 6 and 4 BCE.

The census of Quirinius

The Gospel of Luke mentions a census conducted during the governorship of Quirinius in Syria, linked to Jesus’ birth. However, historical evidence suggests that Quirinius conducted a well-documented census in 6 CE, nearly a decade after Herod’s death. This apparent contradiction has led some scholars to question the Gospel accounts’ chronology or suggest that Luke referenced an earlier, less-documented census.

Astronomical phenomena

The “Star of Bethlehem”, described in Matthew and as a supposed guiding light for the Magi, is often interpreted as a celestial event. Astronomers have proposed several candidates for this event, including a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 7 BCE, a comet in 5 BCE, or a nova. These dates further support the notion that Jesus was born before Year 1 CE.

Calendar inconsistencies

Dionysius’ calculation of Jesus’ birth was likely influenced by limited historical records and the use of Roman dating conventions. He appears to have underestimated the length of time between the founding of Rome (753 BCE) and Herod’s reign, leading to a misalignment of several years.

Errors and implications of the “Anno Domini” system

While the “Anno Domini” system remains a cornerstone of global timekeeping, its inaccuracies have prompted ongoing debate among historians and chronologists. These errors highlight the challenges of reconstructing timelines from fragmentary ancient records and underscore the subjectivity inherent in organizing historical time.

The absence of Year 0

The omission of a “Year 0” complicates mathematical calculations involving dates across the BCE/CE divide. For instance, the year 1 BC is immediately followed by 1 CE, creating a one-year discrepancy in time spans that cross this boundary.

Regional dating systems

Before the widespread adoption of the “Anno Domini” system, various regions used their own dating systems, based on regnal years, Olympiads, or other events. This lack of standardization adds complexity to historical chronology and often requires extensive cross-referencing to align different timelines.

The “phantom time” hypothesis

One of the more controversial theories about the inconsistencies in historical timekeeping is the “phantom time hypothesis”, proposed by German historian Heribert Illig in the 1990s. Illig argued that approximately 297 years of the early Middle Ages (614–911 CE) were fabricated, making the current year an overestimation by nearly three centuries.

Illig’s hypothesis is based on several claims:

- Sparse archaeological evidence: Illig noted a perceived lack of reliable archaeological records from the early Middle Ages, particularly during the reigns of Charlemagne and his successors.

- Chronological inconsistencies: He argued that medieval chronologies contain gaps and anomalies, suggesting intentional tampering.

- Political motivations: According to Illig, the “missing centuries” were invented by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto III and Pope Sylvester II to place themselves closer to the symbolic year 1000 CE.

Mainstream historians reject the “phantom time hypothesis” as baseless. They point to:

- Extensive evidence: Numerous documents, coins, and artifacts have been reliably dated to the early Middle Ages, contradicting Illig’s claims.

- Astronomical consistency: Recorded solar and lunar eclipses align with the traditional timeline, providing an independent verification of historical dates.

- Faulty methodology: Critics argue that Illig’s selective use of evidence and misinterpretation of historical sources undermine his conclusions.

While intriguing, the “phantom time hypothesis” is widely regarded as a fringe theory that lacks credible support.

A modern perspective on Christian time counting: Cultural imposition versus universal utility

The “Anno Domini” system, rooted in Christian theology, has become the de facto global standard for dating events, largely due to European colonialism and the rise of Western hegemony in modern geopolitics. However, this universal adoption raises important ethical questions in today’s diverse and increasingly secular world.

For cultures with non-Christian religious or historical traditions, the use of a calendar system explicitly tied to Jesus Christ’s birth can be seen as a remnant of cultural and religious imperialism. For instance:

- Islamic, Buddhist, and Hindu traditions maintain their own dating systems, such as the Hijri calendar, the Buddhist Era (BE), and the Saka calendar, yet must conform to the Gregorian calendar in international contexts.

- Indigenous cultures, often suppressed or marginalized during European colonization, had their own seasonal or astronomical timekeeping systems, many of which were lost or devalued.

The imposition of the “Anno Domini” system in these contexts is not merely a practical issue but one of identity and recognition. By privileging a Christian framework, there is an implicit devaluation of other cultural narratives and histories.

Thailand’s version of the lunisolar Buddhist calendar. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Utility versus inclusivity

From a practical standpoint, a globally standardized calendar system facilitates international communication, trade, and cooperation. The Gregorian calendar, as part of this system, provides a shared framework for organizing time and synchronizing activities. However, the utility of this system does not negate the need for cultural inclusivity:

- Secular alternatives: Some have advocated for replacing “Anno Domini” (CE) and “Before Christ” (BC) with the secular terms “Common Era” (CE) and “Before Common Era” (BCE). This change preserves the calendar system while removing explicit religious references, making it more neutral for global use.

- Pluralistic recognition: Efforts could also be made to incorporate other cultural calendars into official documentation, where appropriate. For example, dual-dating systems in academic and governmental contexts could acknowledge non-Christian timekeeping traditions.

The challenge of laicism

In secular societies that champion laicism, or the separation of religion and state, the continued use of a calendar system tied to Christian theology can appear contradictory. While the Gregorian calendar itself is no longer explicitly tied to religious observances, its origins remain.

To balance practicality with secular principles, some argue for clearer recognition of the calendar’s historical context without privileging it ideologically. This includes teaching its origins in schools, acknowledging its limitations, and fostering dialogue about alternative or supplementary systems.

A path forward

Ultimately, the question of timekeeping transcends logistical convenience. It touches on cultural respect, historical recognition, and the values of pluralism. While abandoning the Gregorian calendar entirely may not be practical, greater sensitivity to its Christian roots and the incorporation of diverse cultural timekeeping traditions can help foster a more inclusive global perspective. This approach aligns with modern laicism, ensuring that no single worldview is imposed while respecting the shared need for cooperation in an interconnected world.

Conclusion

The “Anno Domini” system, while revolutionary in its re-centering of history around the figure of Christ, reflects the limitations and subjectivities of its origins. Dionysius Exiguus’ miscalculation of Jesus’ birth year, coupled with the broader inaccuracies of historical chronology, highlights the challenges of reconstructing time from incomplete records. The persistence of debates about fabricated centuries, though largely discredited, underscores how timekeeping is both a scientific endeavor and a cultural construct shaped by political, religious, and ideological forces.

In today’s pluralistic world, the universal use of a system rooted in Christian theology raises questions about inclusivity and cultural respect. While the Gregorian calendar and its “Anno Domini” framework provide essential global utility, they remain tethered to a specific worldview. Recognizing this history and exploring ways to integrate or acknowledge alternative cultural timekeeping systems could foster greater inclusivity without compromising practicality.

Ultimately, timekeeping is not just about marking years but about narrating history, identity, and values. The ongoing refinement of our historical understanding – along with efforts to address the colonial and theological legacies of global systems – represents a critical step toward a more equitable and inclusive view of human chronology. Both, historical accuracy and cultural sensitivity need to be balanced to ensure that the ways we measure time reflect not only practicality but also the diversity of human experience.

References and further reading

- Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah, 1977, Geoffrey Chapman, ISBN: 978-0225662061

- Georges Declercq, Anno Domini: The Origins of the Christian Era, 2000, Brepols Publishers, ISBN: 978-2503510507

- Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400-800, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199212965

- John M. Steele, Calendars and Years II: Astronomy and Time in the Ancient and Medieval World, 2011, Oxbow Books, ISBN: 978-1842179871

- Matthias Becher, Charlemagne, 2005, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300107586

- Wikipedia article on Dionysius Exiguus’ time calculationꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Calendar eraꜛ

- Wikpedia article on the Common Eraꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Buddhist calendarꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Year Zeroꜛ

comments