25th of December: The origins of Christmas and its potential connections to pagan festivals

The date of December 25th, celebrated worldwide as Christmas, is traditionally recognized as the birthday of Jesus Christ. However, historical research suggests that this date was not chosen based on evidence of Jesus’ actual birthdate. Instead, it aligns with significant pre-Christian festivals, particularly those associated with the Roman sun god Sol Invictus and possibly the cult of Mithras. This intentional overlap reflects the early Church’s efforts to integrate Christian celebrations into the cultural and religious world of the Roman Empire, raising critical questions about the impact of this syncretism on the authenticity of Christian identity and practice.

December 25th and Sol Invictus

The festival of Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) was formally established in 274 CE by the Roman Emperor Aurelian, who sought to unify the Roman Empire through a common religious framework. Aurelian declared December 25th as the official birthday of Sol Invictus (Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, ‘birthday of the Invincible Sun’), aligning it with the winter solstice, an astronomical turning point symbolizing the victory of light over darkness. This association carried deep symbolic resonance, reinforcing the imagery of renewal and strength.

Coin of Emperor Constantine I depicting Sol Invictus with the legend soli invicto comiti, c. 315. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Coin of Emperor Constantine I depicting Sol Invictus with the legend soli invicto comiti, c. 315. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Origins of Sol Invictus

While the formal institution of Sol Invictus was a Roman innovation, its roots likely draw upon earlier traditions of solar worship, which were widespread across the ancient world. The concept of a supreme solar deity was not unique to Rome and had been celebrated in various forms, including:

- Syrian solar cults: Aurelian’s decision to elevate Sol Invictus may have been influenced by the solar deity Elagabalus, worshiped in Emesa (modern-day Homs, Syria). The cult of Elagabalus was briefly promoted to prominence in Rome during the reign of the Emperor Elagabalus (218–222 CE), who was a high priest of the deity. Aurelian likely borrowed elements from this tradition to create a more universal solar figure.

- Mithraic connections: Mithraism, a mystery religion popular among Roman soldiers, also emphasized solar imagery. Mithras was often depicted as a deity associated with the sun, light, and cosmic order. However, while Mithras was linked to the sun, he was not identical to Sol Invictus. Instead, Mithras may have been seen as a companion or subordinate to Sol Invictus. The two cults appear to have coexisted in Rome, with some overlap in iconography and symbolism. The establishment of Sol Invictus as an imperial cult may have absorbed or overshadowed certain Mithraic elements, consolidating diverse solar traditions under a single, state-sanctioned deity.

- Broader Indo-European traditions: Solar deities and solstice celebrations were common in various Indo-European traditions, from the Vedic Surya in India to the Greek Helios and the Persian Hvar Khshaita. Aurelian’s creation of Sol Invictus could be seen as an attempt to unify these diverse solar cults within the Roman Empire, reflecting its syncretic religious culture.

Aurelian’s creation of Sol Invictus unified diverse solar traditions, reflecting the Roman Empire’s syncretic religious culture. These traditions, ranging from Syrian solar cults to broader Indo-European practices, emphasized themes of cosmic renewal that resonated with Roman imperial ideology.

Sol Invictus and Christianity

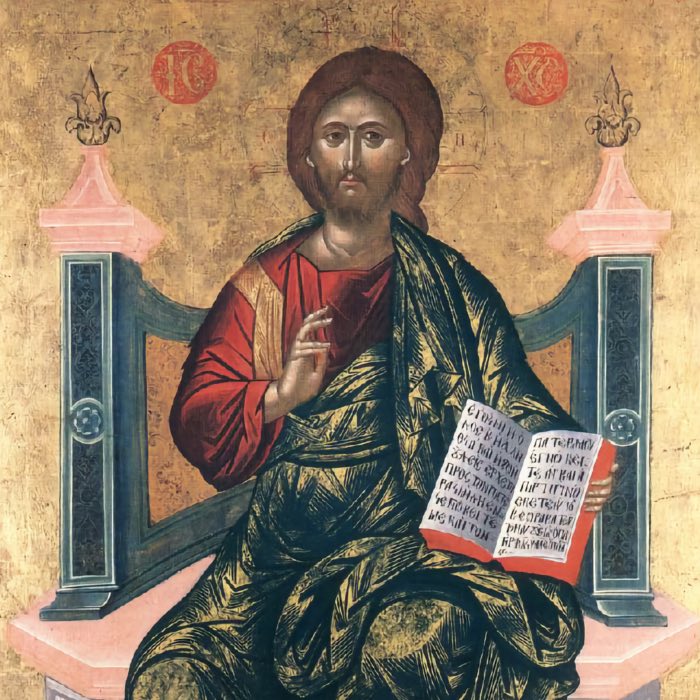

By the 4th century CE, Christianity had begun its ascent as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, particularly under Emperor Constantine. The Church, keen to supplant pagan traditions with Christian observances, adopted December 25th as the feast day for the Nativity of Christ. The symbolic alignment between Jesus and solar imagery, emphasized in Christian theology, made this transition relatively seamless.

Early Christian thinkers drew explicit parallels between Christ and the sun:

- Biblical references: Passages such as John 8:12 (“I am the light of the world”) and Malachi 4:2 (“the sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings”) reinforced the association of Jesus with light and renewal.

- Theological interpretations: Church Fathers, including Augustine of Hippo, frequently likened Christ to the sun, portraying him as the ultimate source of spiritual illumination and life.

By co-opting the date and themes of Sol Invictus, the Church not only offered a theological justification for the new celebration but also facilitated the conversion of a population familiar with solar worship. This strategy exemplifies the broader process of syncretism through which Christianity integrated and transformed elements of existing religious practices. However, it also raises questions about whether this approach diluted the theological purity of Christianity or demonstrated its adaptability to diverse cultural contexts.

Mosaic of Sol in Mausoleum M in the Vatican Necropolis, 3rd c. CE. It is assumed that this Sol Invictus depiction represents Christ. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Early debates and the adoption of December 25th

The New Testament provides no explicit date for Jesus’ birth. Early Christian communities celebrated the nativity on various dates, including January 6th (the feast of Epiphany) and March 25th (the Annunciation). By the 4th century, however, December 25th became widely recognized in the Western Church.

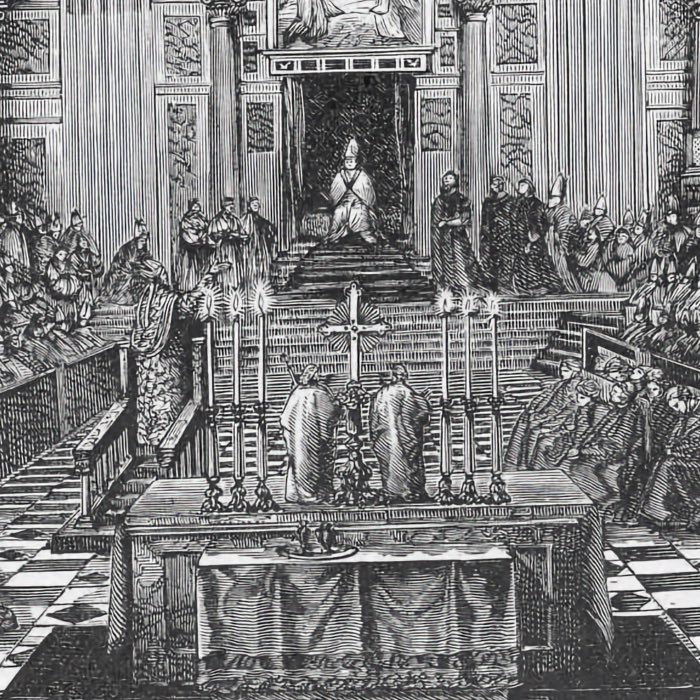

The Chronography of 354, a Roman almanac, marks December 25th as both the feast of Sol Invictus and the Nativity of Christ. This overlap suggests a deliberate Christian appropriation of the date. Some Church leaders, including Pope Leo I, argued that celebrating Jesus’ birth on this date symbolized his role as the “true sun”, replacing the pagan sun gods. However, this alignment also created a theological tension: was the adoption of this date a necessary compromise for the Church’s survival, or did it mark the beginning of a shift away from Jesus’ core teachings toward an institutionalized faith that prioritized external symbols over inner transformation?

Syncretism, adaptation, and critique

The integration of pagan symbols and dates into Christian observances demonstrates the Church’s pragmatic approach to spreading its message. However, this syncretism invites critical reflection on its broader implications:

- Cultural reappropriation or erasure: While some view the alignment of Christian and pagan traditions as a form of cultural assimilation, others argue that it represented an erasure of pre-Christian beliefs. This raises questions about the ethics of such practices, particularly when conversions were accompanied by coercion or social pressure.

- Impact on Christian identity: The adoption of December 25th reflects a tension between preserving the distinctiveness of Christian theology and making it accessible to a diverse and often resistant population. Did this strategy strengthen the Church’s mission, or did it risk diluting its foundational principles?

- Theological and institutional implications: Ritualizing Jesus’ birth around existing pagan festivals contributed to the institutionalization of Christianity. While this facilitated unity and standardization, it also marked a departure from the simplicity and humility emphasized in Jesus’ teachings, shifting focus toward hierarchical control and external practices.

The cult of Mithras and debated connections

Some scholars suggest, that the Mithraic mysteries also celebrated a festival on December 25th. Mithras, a god of light and salvation originating from Persian traditions, was believed to have been born from a rock (petra genetrix) in a cave. This imagery of Mithras’ miraculous birth paralleled early Christian nativity traditions, which sometimes depicted Jesus’ birth in a cave-like setting.

Mithra (left) in a 4th-century investiture sculpture at Taq-e Bostan in western Iran. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Mithra (left) in a 4th-century investiture sculpture at Taq-e Bostan in western Iran. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Mithraism appealed particularly to Roman soldiers and emphasized themes of cosmic struggle and renewal. The timing of Mithras’ festival on December 25th, coupled with the imagery of his birth, may have influenced early Christian celebrations of Jesus’ nativity. The Church’s decision to adopt this date could thus be seen as a strategic move to assert Christian theology over Mithraic traditions, framing Jesus as the ultimate savior and light-bringer.

Cult relief of the god Mithras, 2nd/3rd century, found in the Rhineland. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Cult relief of the god Mithras, 2nd/3rd century, found in the Rhineland. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Depiction of Mithras (Sol Invictus), 2nd century, British Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Right: Depiction of Christ from Hinton St Mary, 4th century, British Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

However, the parallels between Mithraism and Christianity remain contested, with many scholars emphasizing the distinct theological frameworks and social contexts of the two traditions.

Psychological and institutional aspects of ritualization

The choice of December 25th, along with its associated rituals, reflects a broader human desire for tangible symbols through which abstract theological concepts can be experienced. Aligning the Nativity with existing festivals provided a concrete anchor for faith, allowing early Christians to engage with complex theological ideas in accessible ways.

However, this process of ritualization also had unintended consequences. By prioritizing external expressions of belief, the Church risked overshadowing the internal transformation central to Jesus’ message. Over time, this focus on ritual and hierarchy contributed to the development of a more dogmatic and institutionalized Christianity, creating a tension between its cultural expressions and theological integrity.

Scholarly perspectives on the date’s significance

Modern scholarship offers a range of interpretations about the significance of December 25th as the date for Christmas. Key points include:

- Symbolic alignment with the solstice: The winter solstice, celebrated across various cultures, marked a pivotal moment of renewal as the days began to lengthen. This astronomical phenomenon symbolized hope, light, and the victory over darkness. For early Christians, this resonated deeply with the theological idea of Jesus as the “light of the world”, providing a compelling symbolic backdrop for the Nativity.

- Strategic syncretism: Many scholars highlight the Church’s pragmatic approach in aligning Christian celebrations with existing pagan festivals, such as the festival of Sol Invictus. By integrating elements of these popular observances, the Church facilitated conversions and provided continuity for communities transitioning to Christian worship. This syncretic approach allowed Christianity to assimilate and transform existing traditions.

- Theological emphasis on light: Early Christian writers frequently employed the metaphor of light to describe Jesus’ role as a bringer of salvation and spiritual illumination. Passages such as Isaiah 9:2 (“The people walking in darkness have seen a great light”) and John 1:5 (“The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it”) reinforced this imagery. The theological association between light and Christ provided a natural bridge to celebrations tied to the solstice.

- Mithraic and solar parallels—debated connections: The relationship between Mithraism, Sol Invictus, and Christianity remains a subject of debate among scholars:

- Arguments for connection: Some scholars argue that Mithraic traditions, with their emphasis on solar imagery and the birth of Mithras, may have influenced the selection of December 25th. In particular, Mithras’ association with cosmic order and light parallels Christian themes of Christ as the divine illuminator. The overlap in symbols, such as the sun and light, suggests a possible interplay between Mithraic rituals and the broader Roman celebration of Sol Invictus.

- Arguments against connection: Others maintain that Mithraism and Sol Invictus were separate traditions with limited overlap. While Mithraic imagery included solar elements, Mithras was not inherently equated with the sun god. Scholars also point out that Mithraism was primarily a mystery religion, accessible only to initiates, and lacked the public prominence of Sol Invictus. This exclusivity would have limited its cultural influence compared to the state-sponsored worship of Sol Invictus.

- No direct link to Christmas: A growing body of scholarship suggests that the choice of December 25th for Christmas was primarily influenced by internal Christian theology rather than direct borrowing from Sol Invictus or Mithraism. These scholars argue that the date aligns with early Christian calculations of Jesus’ conception and birth based on symbolic or liturgical reasons rather than an overt appropriation of pagan festivals.

- The declining prominence of Mithraism: By the 4th century, Mithraism had begun to wane, overshadowed by the rise of Christianity and imperial endorsement of Sol Invictus. Consequently, while Mithraic traditions might have influenced earlier Roman solar worship, their role in shaping the celebration of December 25th was likely minimal compared to the broader cultural significance of Sol Invictus.

These scholarly perspectives illuminate the complexity of choosing December 25th as the date for Christmas, revealing a multifaceted interplay of theological interpretation, cultural adaptation, and political strategy. Reflecting on this historical evolution invites a broader examination of the Church’s ability to navigate cultural contexts while retaining its spiritual mission.

Conclusion

The association of Jesus’ birth with December 25th illustrates the Church’s ability to navigate the complexities of cultural adaptation within the diverse and often politically charged context of the Roman Empire. By aligning Christian celebrations with existing pagan festivals, the Church facilitated the integration of new converts and established Christianity as a dominant cultural force. However, this pragmatic approach also introduced enduring debates about the balance between preserving theological integrity and engaging with the prevailing cultural milieu.

Scholars continue to discuss the extent to which the choice of December 25th was influenced by pagan traditions such as Sol Invictus or Mithraism, and whether this decision represents syncretism or independent theological reasoning. Critics argue that such alignments risk diluting the core message of Jesus, shifting the focus from personal spiritual transformation to external rituals and institutional power. Proponents, on the other hand, view these adaptations as evidence of the Church’s resilience and its capacity to communicate the Christian message in ways that resonate with diverse cultural contexts.

References and further reading

- Thomas J. Talley, The Origins of the Liturgical Year, 1991, Liturgical Press; 2nd Edition, ISBN: 978-0814660751

- Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, 2006, Pneguin, ISBN: 978-0141022956

- Gaston H. Halsberghe, The Cult of Sol Invictus, 1972, Brill, ISBN: 978-9004308312

- Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah, 1977, Geoffrey Chapman, ISBN: 978-0225662061

- Stephan Berrens, Sonnenkult und Kaisertum von den Severern bis zu Constantin I. (193–337 n. Chr.), 2004, Steiner, Stuttgart, ISBN: 3-515-08575-0

- Steven E. Hijmans, Sol Invictus, the Winter Solstice, and the Origins of Christmas, In: Mouseion, Vol. 47, No. 3, 2003, p. 377–398

- Steven E. Hijmans, Sol: The Sun in the Art and Religions of Rome, 2009, Groningen, ISBN: 978-90-367-3931-3

- Martin Wallraff, Christus verus sol. Sonnenverehrung und Christentum in der Spätantike, 2001, Aschendorff, ISBN: 3-402-08115-6

- Roger Beck, The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire: Mysteries of the Unconquered Sun, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199216130

- McGowan, Andrew, Ancient Christian Worship: Early Church Practices in Social, Historical, and Theological Perspective, 2016, Baker Academic, ISBN: 978-0801097874

- Kelly, Joseph F., The Origins of Christmas, 2014, Liturgical Press, ISBN: 978-0814648605

- Alföldi, Andreas, The Conversion of Constantine and Pagan Rome, 1969, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198143567

comments