St. Kolumba in Cologne: A beacon against the war and a symbol of resilience and resurrection

St. Kolumba, one of Cologne’s historic churches, is a symbol of both the city’s rich medieval heritage and its capacity to rise from the ashes of destruction. The church was among the many historical sites severely damaged during World War II. Today, while much of the original structure no longer stands, the legacy of St. Kolumba endures, most notably through the poignant Madonna in den Trümmern (Madonna of the Ruins) and the modern Kolumba Museum that integrates its ruins. Here we focus on the history of St. Kolumba, from its founding to its destruction and transformation. In a later article, we will explore the 2007 opened Kolumba Museum.

St. Kolumba Madonna in den Truemmern. The integration of the church ruins into the new Kolumba Museum building can be seen.

St. Kolumba Madonna in den Truemmern. The integration of the church ruins into the new Kolumba Museum building can be seen.

Early history of St. Kolumba

The origins of St. Kolumba date back to the medieval period, when it served as a parish church for the bustling city of Cologne. Dedicated to St. Columba, an Irish missionary saint, the church became an important spiritual and social center within the city. Its location in the heart of Cologne, near today’s bustling shopping districts, made it a focal point for the religious life of the local community.

The church was first mentioned in historical documents around 980. At that time, it was still a small single-nave church dependent on the ‘Domkirche’, the predecessor of today’s Cologne Cathedral, which was consecrated in 873. An early Romanesque baptismal font from the church, excavated around 1837, also points to an early date in the 11th to 12th century. Over the centuries, St. Kolumba underwent several reconstructions and expansions, reflecting the city’s growth and the church’s rising prominence. Its architectural style evolved, blending Romanesque and later Gothic elements, which were common in Cologne’s medieval churches.

The small predecessor church initially became a three-aisled church in the 12th century. Later, it was expanded into a five-nave late Gothic hall church in the 15th century, probably due to the increased space requirements of the steadily growing congregation. In the 17th century, the choir was vaulted and the interior of the church was adapted to the Baroque style of the time. Extensive restoration work was carried out on the church building in the 19th century.

The church housed some of the most important works of Old Netherlandish and Old Cologne painting, the Columba Altarpiece by Rogier van der Weyden, the Bartholomew Altarpiece by the Master of the Bartholomew Altarpiece and the Wasservass Calvary.

Destruction during World War II

The turning point in St. Kolumba’s history came during World War II, when Cologne was subjected to heavy bombardment. The church was almost completely destroyed during the Allied air raids in 1943-1944. Like many of Cologne’s historic buildings, St. Kolumba was left in ruins, with only remnants of its walls standing amidst the devastation. One of the most remarkable aspects of the church’s destruction was the survival of a single statue of the Virgin Mary, which would become famously known as the Madonna in den Trümmern (Madonna in the Ruins).

This figure of the Madonna, which remained intact amidst the rubble of the collapsed church, became a symbol of resilience and hope. It represented both the spiritual endurance of the community and a powerful reminder of the devastation of war. The Madonna in den Trümmern quickly gained iconic status and became a site of pilgrimage for those seeking solace and reflection in the post-war period.

Today’s Mary’s Chapel, built in the ruins of the former St. Kolumba church in the 1950s by architect Gottfried Böhm. The central element is the Madonna in the ruins.

Today’s Mary’s Chapel, built in the ruins of the former St. Kolumba church in the 1950s by architect Gottfried Böhm. The central element is the Madonna in the ruins.

Madonna in den Trümmern

The Madonna in den Trümmern has come to symbolize not only the survival of St. Kolumba but also the survival of Cologne itself. As the city slowly rebuilt after the war, this statue served as a focal point for collective mourning and recovery. It stands today as one of Cologne’s most powerful symbols of faith enduring through catastrophe.

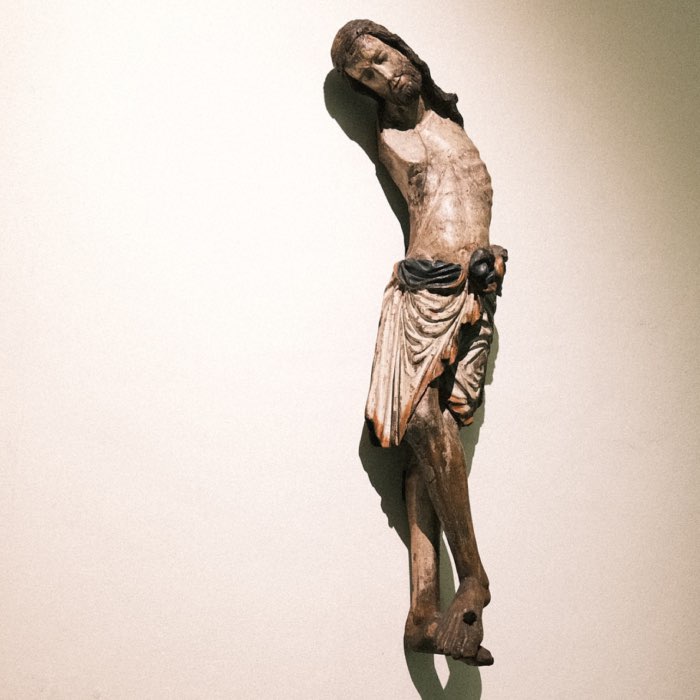

The Madonna in the ruins, created around 1460/80.

The Madonna in the ruins, created around 1460/80.

The statue of the Madonna, although relatively small, represents the resilience of a people whose city was nearly flattened by bombings. The simple image of the Virgin Mary cradling the infant Christ amidst the rubble of the destroyed church encapsulates the idea that, even in moments of great loss and destruction, hope can persist. The Madonna continues to be revered and visited today, long after the war’s end.

After the war, the ruins of St. Kolumba stood as a somber reminder of the destruction that had befallen Cologne. The decision was eventually made not to fully rebuild the church, but rather to preserve the site as a memorial. In the 1950s, a small chapel was constructed among the ruins to house the Madonna in den Trümmern, allowing the faithful to continue visiting the site for prayer and reflection.

Impressions of the Mary’s Chapel

Here are some further impressions of the Mary’s Chapel from a visit in August 2024:

Mary’s Chapel. Mosaic floor made from fragments of the destroyed church (1949)

Mary’s Chapel. Mosaic floor made from fragments of the destroyed church (1949)

Light show on the roof of the Mary’s Chapel. The light play comes from the illuminated ‘Engelfenster’ (Angel Window) by Ludwig Gies (1954).

Light show on the roof of the Mary’s Chapel. The light play comes from the illuminated ‘Engelfenster’ (Angel Window) by Ludwig Gies (1954).

The Marien-Kapelle chapel (architect Gottfried Böhm), built in 1950, seen from the outside, from the archaeological excavation hall. Stained glass: ‘Engelfenster’ (Angel Window) by Ludwig Gies (1954).

The Marien-Kapelle chapel (architect Gottfried Böhm), built in 1950, seen from the outside, from the archaeological excavation hall. Stained glass: ‘Engelfenster’ (Angel Window) by Ludwig Gies (1954).

Statue of Anna Selbdritt, around 1500.

Statue of Anna Selbdritt, around 1500.

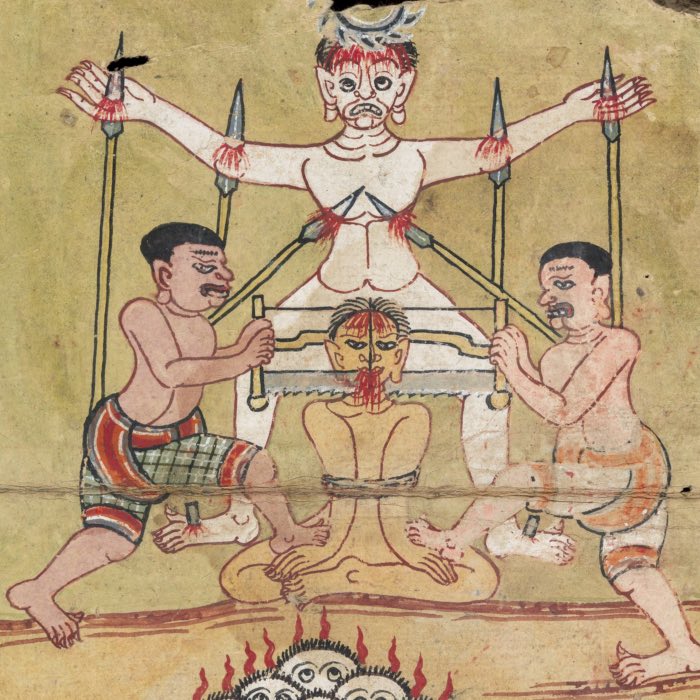

Sculpture scene on the baptismal font lid.

Sculpture scene on the baptismal font lid.

Way of the Cross, designed by Rudolf Peer, is engraved in the masonry of the Blessed Sacrament.

Way of the Cross, designed by Rudolf Peer, is engraved in the masonry of the Blessed Sacrament.

Way of the Cross, further views.

Way of the Cross, further views.

Way of the Cross, further views.

Way of the Cross, further views.

Altar of the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament. The altar, with a tabernacle created by the goldsmith Elisabeth Treskow, forms the dominant focal point of this chapel. The altar is surrounded by stylized ‘trees of life’ carved out of light-coloured marble, reaching up to the round light opening in the ceiling. Prayer benches have been placed around the altar for devotion.

Altar of the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament. The altar, with a tabernacle created by the goldsmith Elisabeth Treskow, forms the dominant focal point of this chapel. The altar is surrounded by stylized ‘trees of life’ carved out of light-coloured marble, reaching up to the round light opening in the ceiling. Prayer benches have been placed around the altar for devotion.

Peter Zumthor’s vision of light, space, and history

The most significant transformation came in the 21st century, with the creation of the Kolumba Museum. Designed by Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, the museum incorporated the ruins of St. Kolumba into its modern structure. Today, the chapel is integrated into the new museum building, i.e., into the archaeological excavation hall. The latter allows visitors of the museum to explore the remains of the church and the history of the site.

Today, the chapel as well as the church ruins are integrated into the [Kolumba Museum.

Today, the chapel as well as the church ruins are integrated into the [Kolumba Museum.

This fusion of past and present reflects the ongoing legacy of St. Kolumba and serves as a unique witness of Cologne’s architectural and cultural history. We will explore the Kolumba Museum in more detail in a separate article.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Archaeological excavation hall by architect Peter Zumthor.

Found floor tiles in the archaeological excavation hall.

Found floor tiles in the archaeological excavation hall.

Archaeological remains of the former St. Kolumba (outside area).

Archaeological remains of the former St. Kolumba (outside area).

Ruins of the former St. Kolumba (outside area).

Ruins of the former St. Kolumba (outside area).

Ruins of the former St. Kolumba.

Ruins of the former St. Kolumba.

Ruins of the former St. Kolumba (outside area).

Ruins of the former St. Kolumba (outside area).

Conclusion

St. Kolumba’s story is one of transformation and resilience. From its early days as a parish church to its near-destruction during World War II and its eventual rebirth as part of the Kolumba Museum, the site remains a vital part of Cologne’s historical and spiritual landscape. The Madonna in den Trümmern stands as a lasting symbol of faith and endurance, continuing to draw visitors who seek both solace and a deeper understanding of Cologne’s wartime history. Today, St. Kolumba’s legacy lives on, not only in the 1950s chapel built within its ruins but also in the museum that preserves its memory.

References and further reading

- Sven Seiler, Michael Dodt, Thomas Hölken, Marc Steinmann, Kolumba: Kapelle, 2020, Kolumba, ISBN: 9783981997521

- Stefan Kraus, Anna Pawlik, Martin Struck, Lothar Schnepf, Kolumba: Kapelle, 2020, Kolumba, ISBN: 9783981997521

- Joachim M. Plotzek, Katharina Winnekes, Stefan Kraus, Ulrike Surmann, Marc Steinmann, Michael Dodt, Joachim Oepen, Sven Seiler, Vera Gilgenmann, Lothar Schnepf, Auswahl eins, 2007, Philipp Von Zabern, ISBN: 978-3-931326-56-X

- Website of the Kolumba Museumꜛ

- Wikipedia article on St. Kolumbaꜛ

comments