Baroque splendor as a tool of the Counter-Reformation: St. Mariä Himmelfahrt in Cologne

Located near the Cologne Cathedral, the Catholic parish church of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt stands as one of Cologne’s largest churches, second only to the Cathedral itself. Built during the early 17th century, it remains one of the few surviving Baroque architectural monuments in the city. Despite the city’s Gothic-dominated skyline, this Jesuit-designed church offers a remarkable insight into the Baroque era’s religious and architectural innovations – and it illustrates the Catholic Church’s efforts to reaffirm its power through monumental and elaborate religious structures. In this post, we briefly to explore the history, architecture, and artistic elements of this church, highlighting its significance in Cologne’s religious and cultural landscape.

Historical background

The origins of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt (Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary) date back to 1618 when the Jesuits laid its foundation stone under the direction of architect Christoph Wamser. Wamser had previously designed the Jesuitenkirche in Molsheim, Alsace, which heavily influenced the plans for Cologne’s St. Mariä Himmelfahrt. As with many Jesuit churches of the period, it was conceived as a grand symbol of the Counter-Reformation, reflecting the Catholic Church’s efforts to reaffirm its power through monumental and elaborate religious structures. Wamser oversaw the construction until 1623, after which Valentin Boltz took over the building’s final stages and its interior design. The church was completed in 1678.

Floor plan with college. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Floor plan with college. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

In 1794, following the invasion of Cologne by French revolutionary forces, the church was profaned and repurposed as a “temple of decadence” during the secularization of church properties. However, it was rescued from destruction by Cologne citizens, including the efforts of city councilman Laurenz Fürth. The church was reconsecrated as a place of worship in 1803, and since then, it has been dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

The Baroque facade of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt.

The Baroque facade of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt.

While the survival of the church during the French occupation could be accounted as a victory for Catholicism, however, the same occupation regime granted the Protestant community the right to worship in the city. Many of the city’s Catholic monastic churches were dissolved and repurposed, and the Antoniterkirche was handed over to the Protestant community, making it one of the first Protestant churches in Cologne. And decades later, under the rule of Prussia, the Protestant community was even able to build their own representative church, the Trinitatiskirche, which is prominently located in the southern part of Cologne’s Old Town.

During World War II, St. Mariä Himmelfahrt suffered severe damage, leaving only its outer walls standing. The post-war restoration of the church lasted from 1949 to 1979, meticulously reconstructing its Baroque glory. Today, it serves as an important reminder of Cologne’s religious and architectural heritage.

St. Mariä Himmelfahrt, entrance.

St. Mariä Himmelfahrt, entrance.

Architectural features

St. Mariä Himmelfahrt is a three-aisled basilica with seven bays and galleries, designed in a style reminiscent of early Jesuit churches across Europe. Its layout includes a narrow transept, side chapels, and a choir with a distinctive hexagonal closing. The façade, framed by two prominent towers, creates a grand entrance to the building, with large columns and statues of Jesuit saints like Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier adorning the structure. Above the main portal, a crest belonging to Duke Maximilian of Bavaria — one of the church’s major patrons — symbolizes the significant political and religious ties between Cologne and the House of Wittelsbach.

Nave with view towards the choir and the pompous high altar.

Nave with view towards the choir and the pompous high altar.

The church’s Baroque interior, although reconstructed after the war, retains many of its original elements. Six paired Tuscan columns separate the nave from the aisles, while the interior galleries and organ loft are supported by late Gothic-inspired tracery and delicate ribbed vaults. The large windows allow abundant light to enter the space, creating an ethereal atmosphere that underscores the Baroque love for light and spatial drama.

Impressions of the interior: Baroque elements and figurative ornamentation in the nave.

Impressions of the interior: Baroque elements and figurative ornamentation in the nave.

Impressions of the interior: figurative ornamentation in the nave.

Impressions of the interior: figurative ornamentation in the nave.

A wooden statue of Saint Christopher holding the Christ Child?

A wooden statue of Saint Christopher holding the Christ Child?

Notable artistic elements

One of the most remarkable features of the church is its towering high altar, completed in 1628 with funds from Archbishop Ferdinand of Bavaria. It stands 22.5 meters high and extends across three tiers, occupying the full height of the choir. The altar is decorated with intricately carved figures, including apostles and Old Testament prophets, many of which were replaced after World War II using fragments salvaged from the original structure.

Main altar from 1628. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Main altar from 1628. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another example of Jesuit theatricality is the tabernacle, a temple-like structure with twisting columns and angelic figures. The baroque tabernacle was reconstructed in the post-war era, complete with its original mechanism, which allowed a monstrance to be ceremoniously revealed during the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament.

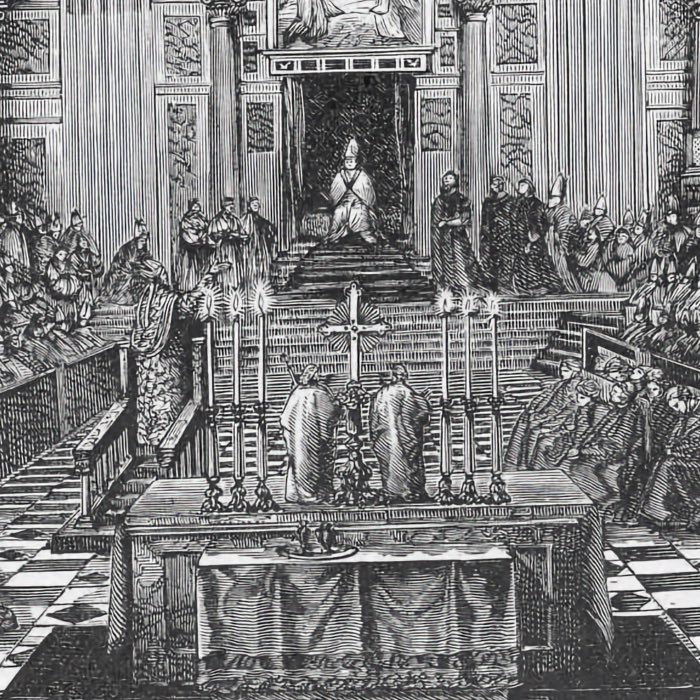

The Baroque epoch: An expression of the Counter-Reformation

The Baroque period in Europe, spanning roughly from the late 16th century to the early 18th century, was deeply intertwined with the Catholic Church’s efforts to reaffirm its dominance in the wake of the Protestant Reformation. This era saw the Catholic Church leveraging art, architecture, and music to evoke emotion, inspire devotion, and symbolically underscore its authority. St. Mariä Himmelfahrt is a prime example of how the Church harnessed the grandiosity and visual drama of Baroque aesthetics to reinforce its presence and power, especially in a city like Cologne, a historic stronghold of Catholicism.

Baroque art and architecture were deliberately designed to awe and inspire, with their intricate, but exaggerated and blown-up details, dynamic forms, and intense use of strong colors and gold. Jesuit churches like St. Mariä Himmelfahrt, which served as centers of Catholic teaching and evangelism, were intentionally extravagant, countering the more austere Protestant churches of the time. By invoking classical forms, such as the grand basilicas of ancient Rome, Baroque architecture aligned itself with the continuity and timelessness of the Catholic faith. Every element of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt’s design – its monumental high altar, massive pillars, gilded sculptures, and intricate ceiling frescoes – was crafted to reflect the power and glory of the Catholic Church. The architecture itself became a form of religious theater, aiming to pull worshippers away from the world’s distractions and immerse them in a transcendent experience of faith.

The Jesuits, as prominent Counter-Reformation leaders, were particularly adept at using the visual and emotional appeal of Baroque art to convey Catholic values and doctrines. St. Mariä Himmelfahrt’s towering high altar dominates the choir and embodies the Catholic ideal of heaven-reaching splendor (how this relates to Jesus’ commandment of simplicity and poverty should be discussed in a separate post). Carved figures of apostles, prophets, and saints on the altar serve as both religious icons and reminders of the Catholic Church’s esteemed history and sanctified figures. The tabernacle, another prominent feature, showcases Baroque theatricality: twisting columns, angelic figures, and a concealed monstrance that could be ceremonially revealed underscored the sacred mystery and visual opulence the Catholic Church sought to project.

In Cologne, a city rich in Gothic tradition, St. Mariä Himmelfahrt’s Baroque form also served as a statement of the Catholic Church’s adaptability and resilience. The church’s architectural style reflected an assertive, almost confrontational beauty, meant to recapture the hearts and minds of its followers and to draw them back from the allure of Protestant ideas. The decorative excess, attention to grandiosity, and emotionally charged artistry found in the church exemplify how the Baroque became a visual embodiment of the Counter-Reformation: a display of Catholicism’s triumph over its opponents.

The lasting impact of this architectural and artistic movement demonstrates how the Baroque was more than a style – it was an instrument of religious influence and persuasion, designed to evoke wonder, humility, and devotion in all who entered. As a preserved monument in Cologne’s largely Gothic skyline, the church remains a testament to an era when art and architecture were potent tools in the Catholic Church’s campaign to restore its spiritual and temporal authority.

Conclusion

St. Mariä Himmelfahrt stands as one of the rare examples of Baroque architecture in Cologne, embodying the religious zeal and artistic grandeur of the Counter-Reformation. This Jesuit church was a vital component of the Catholic Church’s response to Protestantism, presenting a space where the opulence of faith was meticulously crafted into every architectural detail, artwork, and liturgical feature. Its imposing structure and elaborate interior were intentionally designed to not only inspire devotion but also to assert the enduring power and influence of the Catholic Church within a city steeped in Gothic tradition.

The church’s lavish Baroque elements serve as a reminder of how art and architecture were wielded as powerful tools of religious affirmation during a period of intense spiritual and ideological competition. Through its towering high altar, dynamic sculptures, and dramatic interplay of light and space, St. Mariä Himmelfahrt captures the spirit of an epoch in which the Catholic Church sought to reaffirm its dominance and invite the faithful back to its fold through a deeply immersive, visually captivating experience. Today, this architectural gem remains a testament to the era’s vision of Catholic grandeur, symbolizing the unchanging, rigid self-perception of an institution in the midst of a changing religious landscape and cultural changes.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on St. Mariä Himmelfahrtꜛ

- Website of St. Mariä Himmelfahrtꜛ

- Manfred Becker-Huberti, Günter A. Menne, Die Kölner Kirchen, 2004, J. P. Bachem Verlag, ISBN: 3-7616-1731-3

- Jürgen Kaiser, Florian Monheim, Die großen romanischen Kirchen in Köln, 2017, Greven Verlag, ISBN: 9783774306875

- Ulrich Krings, Otmar Schwab, Köln, die romanischen Kirchen - Zerstörung und Wiederherstellung, 2007, Bachem, ISBN: 9783761619643

- Hiltrud Kier, Die Romanischen Kirchen in Köln, 2014, Hrsg.: Förderverein Romanische Kirchen Köln e. V. 2. Auflage, ISBN: 978-3-7616-2842-3

comments