From ukiyo-e to horimono: The Japanese art of tattooing and its historical roots

Horimono (彫り物), the traditional Japanese art of tattooing, is a deeply rooted cultural practice that actually dates back thousands of years. Its history is intertwined with Japan’s social evolution, spiritual beliefs – and the ukiyo-e woodblock printing tradition. From its ancient origins to its association with the yakuza and its current resurgence as an art form, horimono reflects Japan’s complex relationship with tattooing – oscillating between reverence, stigma, and admiration – and the transformation of ukiyo-e into a new, living canvas through the art of tattooing.

Hand-colored photograph of a japanese tattoo from the Meiji era, by Kimbei or Stillfried. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Horimono? Irezumi? What’s the difference?

Before we begin, let’s first clarify some terms. Horimono and irezumi are often used interchangeably to refer to traditional Japanese tattooing. However, there is a subtle distinction between the two.

Horimono translates to “something that is carved” with “hori” meaning “to carve” and “mono” meaning “object” or “stuff”. Horimono specifically refers to the act of carving or engraving, reflecting the intricate and labor-intensive process of tattooing in Japan. On the other hand, irezumi, which means “inserting ink”, is a more general term that encompasses all forms of tattooing, including modern styles and techniques. Specifically, irezumi refers to the type of tattooing done to mark criminals and the Western style of tattooing that consists of a single design, delineated from the surrounding skin. Punishment by tattooing was called bokukei or bokkei (墨刑). Horimono, in contrast, is considered decorative and takes up the entire body as one continuous canvas. The back is the central motif of the design and dictates the choice of motif for the rest of the body.

Tattoo punishment explanation, Edo period. Source: JETNAKAMURA (Twitter)ꜛ.

Another term, which one may encounter from time to time, is wabori (和彫り). “Wa” is a term that refers to Japan or Japanese, and bori means “carving” or “engraving”. Wabori thus refers to traditional Japanese tattooing that is distinct from Western tattooing styles, which is often referred to as yōbori (洋彫り; with yō meaning “Western”), which is also a slang term for tattooing done with the machine. Wabori emphasizes the use of bold lines, vibrant colors, and intricate designs inspired by Japanese art and culture.

Horimono example: Man with floral arm tattoos. Photograph by Kevin Bidwell (pexels.com)ꜛ (license: free to useꜛ).

Horimono example: Man with floral arm tattoos. Photograph by Kevin Bidwell (pexels.com)ꜛ (license: free to useꜛ).

The techniques used in traditional Japanese tattooing are distinct from those employed in Western tattooing. In Japan, tattoo artists, the horishi (彫り師, 彫物師) use a hand-poking method called tebori (手彫り), which involves manually inserting ink (sumi, 墨) into the skin using a needle attached to a wooden or metal rod. This technique allows for greater precision and control, resulting in more intricate and detailed designs. The slow and deliberate process of tebori is considered a meditative and spiritual experience, with both the artist and the recipient engaging in a shared ritual that goes beyond mere decoration.

Tattooing by hand, i.e., without using of a tattoo machine, is called tebori (手彫り, “to carve by hand”), where just a needle and ink are used. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Tattooing by hand, i.e., without using of a tattoo machine, is called tebori (手彫り, “to carve by hand”), where just a needle and ink are used. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Vice documentary movie “An Inside Look at Hand-Poked Japanese Tattoos” gives an insight into the traditional tebori technique. Source: YouTubeꜛ.

The roots of tattooing in Japan

Ancient beginnings: The spiritual and decorative roots

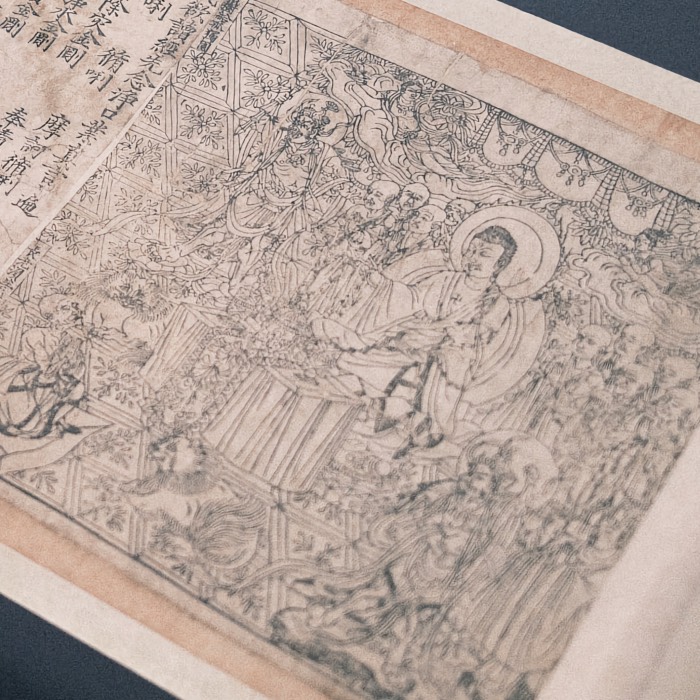

The origins of tattooing in Japan are believed to stretch back to the Jōmon period (circa 10,000 BCE). Some scholars suggest that the cord-marked patterns found on clay figurines from this era might represent tattoos, though this interpretation is not universally accepted. These markings resemble the tattoo traditions seen in other ancient cultures, hinting at a possible spiritual or decorative purpose.

During the subsequent Yayoi period (300 BCE to 300 CE), tattoos were observed and recorded by Chinese visitors to Japan. These tattoos were believed to carry spiritual significance and also served as status symbols. However, conflicting evidence exists; the Kojiki, an ancient Japanese chronicle, suggests that tattooing was not practiced on the mainland of Japan and was instead associated with foreign customs. The Nihon Shoki, another important historical text, mentions that tattooing was a practice among the Ainu people, Japan’s indigenous inhabitants.

The Ainu: Early tattooing practices

The Ainu people, early settlers of Japan, are believed to have used facial tattoos as part of their cultural practices. Chinese records from about 1,700 years ago describe the Wa people, a Chinese term for the Japanese, as divers who adorned their bodies with tattoos, possibly as a form of protection or identification during their aquatic pursuits. These early accounts highlight the long-standing presence of tattooing in Japan, though its meaning and significance varied across different regions and periods.

An Ainu woman with a tattoo around the mouth, collection Bäz, 1910. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Kofun period: Tattoos as punishment

By the Kofun period (300-600), tattoos in Japan began to take on negative connotations. Rather than serving spiritual or decorative purposes, they were increasingly used as a form of punishment for criminals. Markings were applied to offenders as a way to brand and shame them, a practice that would continue for centuries.

The Influence of Buddhism and Confucianism: Tattoos as taboo

As Buddhism and Confucianism began to exert a stronger influence on Japanese culture, the perception of tattoos shifted further. Tattooing came to be seen as barbaric and was increasingly associated with criminality. In the eyes of the Chinese, who had a more developed culture and who influenced Japan’s adoption of Buddhism, tattooing was considered an uncivilized act. Consequently, criminals in Japan were marked with tattoos as a form of punishment and social exclusion. This practice of marking criminals persisted into the Edo period (1603-1868) and contributed to the enduring stigma associated with tattoos in Japan.

The Edo period: The rise of decorative tattoos and the influence of ukiyo-e

The Edo period (1603-1868) marked a significant turning point in the history of Japanese tattooing. While tattoos continued to be used for punitive purposes, a parallel trend emerged that saw the development of tattooing as a sophisticated art form, closely tied to the ukiyo-e tradition.

Left: Zhu Gui from the series The Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1830-1836. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Kyumonryu Shinshin and Chokanko Chintasu, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Senkaji Chao wringing out his cloth, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Yan Qing the Graceful (Roshi Ensei) with all his body tattooed is lifting a heavy beam, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1861. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

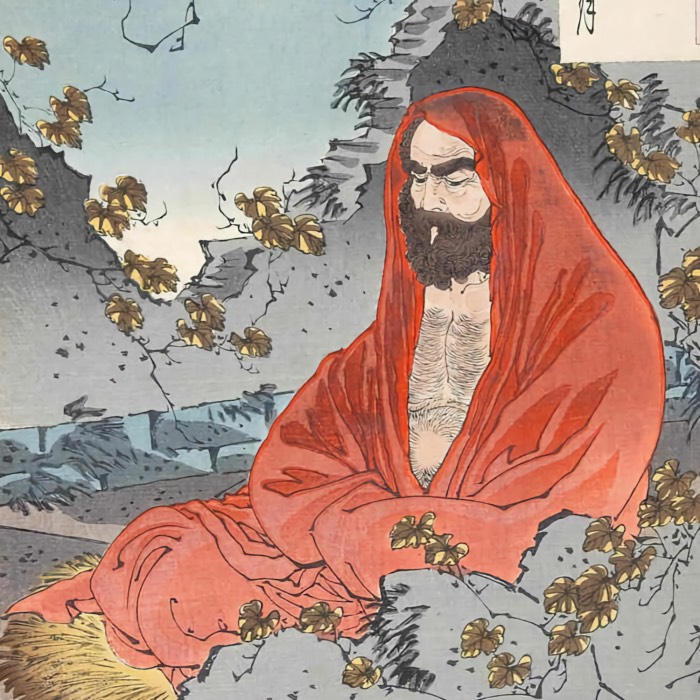

The term hori alludes to the fact that many of Japan’s first modern tattoo artists were originally ukiyo-e woodblock carvers from Edo. The relationship between ukiyo-e and horimono is profound, as both were considered lower forms of art linked to the “floating world” – a term that also refers to the pleasure districts of Edo. These art forms contrasted sharply with the tastes of the upper classes, who were more influenced by Chinese culture and Confucian ideals. Within this environment, horimono emerged and reached its peak in the 1800s, fueled by the growing popularity of ukiyo-e.

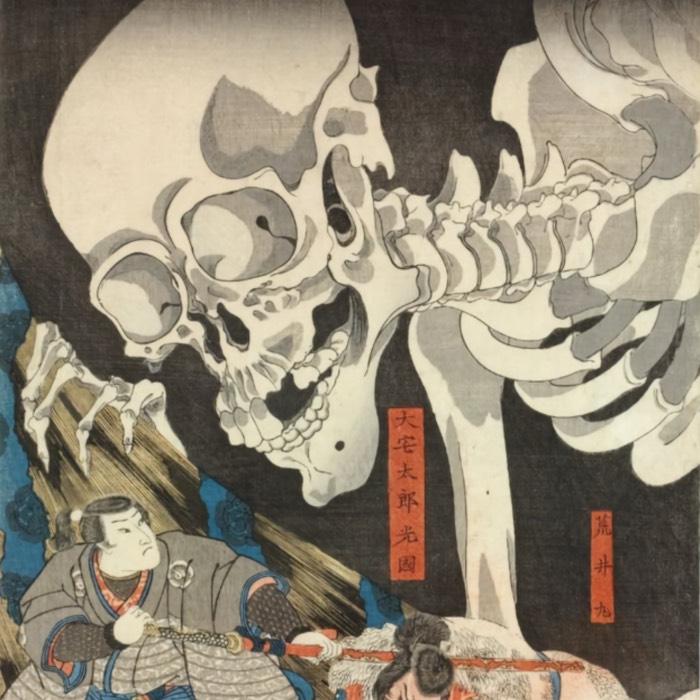

A key example of this symbiotic relationship is the publication of the popular Chinese novel Suikoden in Japan. The novel, known in Chinese as Heroes of the Water Margins, was illustrated with elaborate woodcuts that depicted heroic figures adorned with tattoos of dragons, tigers, flowers, and mythological creatures. The tales of morally complex outlaws – 108 characters who rebelled against corrupt rulers and became folk heroes – resonated deeply with the working class of Edo, who themselves often faced harsh treatment from the upper echelons of society under the Tokugawa shogunate.

Left: Sotoki Sosei, from One of the Eight Hundred Heroes of the Water Margin of Japan, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1827-1830. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Kirenji Toko, from One of the Eight Hundred Heroes of the Water Margin of Japan, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1830-1832. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ (license: public domain).

The novel’s widespread appeal led to numerous illustrated editions being published over more than seven decades, achieving significant commercial success. The most influential version, illustrated by Kuniyoshi, is known as the 108 Heroes of Suikoden. In this edition, many of the heroes were depicted with extensive full-body tattoos, which sparked a growing interest in decorative tattooing among ordinary people. Edo firefighters, craftsmen, carpenters, and laborers were particularly drawn to this trend, as these tattoos became symbols of individuality, bravery, and defiance.

Left: Tengan Isobei, from One of the Eight Hundred Heroes of the Water Margin of Japan, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1830-1832. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ/The British Museumꜛ (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). – Right: The village of the Shi clan on a moonlit night (Shikason tsukiyo), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, ukiyo-e print by Yoshitoshi, 1885. Shui Hu Zhuan” (Jp. Suikoden), relaxes in his home village. He had nine dragons tattooed, therefore he was known as Kumonryu (Nine Dragons). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Skilled woodblock artists, many of whom were proficient in ukiyo-e techniques, began applying their craft to tattooing. They used tools similar to those employed in woodblock carving—chisels, gouges, and specialized inks like Nara ink**, which famously turned blue-green under the skin. These artists elevated tattooing to a new level, creating intricate and expansive designs that covered large portions of the body.

Left: Kabuki Actor, Ichikawa Danjuro IX, ukiyo-e print by Toyohara Kunichika, c. 1880. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Sotoki Sosei, from One of the Eight Hundred Heroes of the Water Margin of Japan, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1827-1830. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ/The British Museumꜛ (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

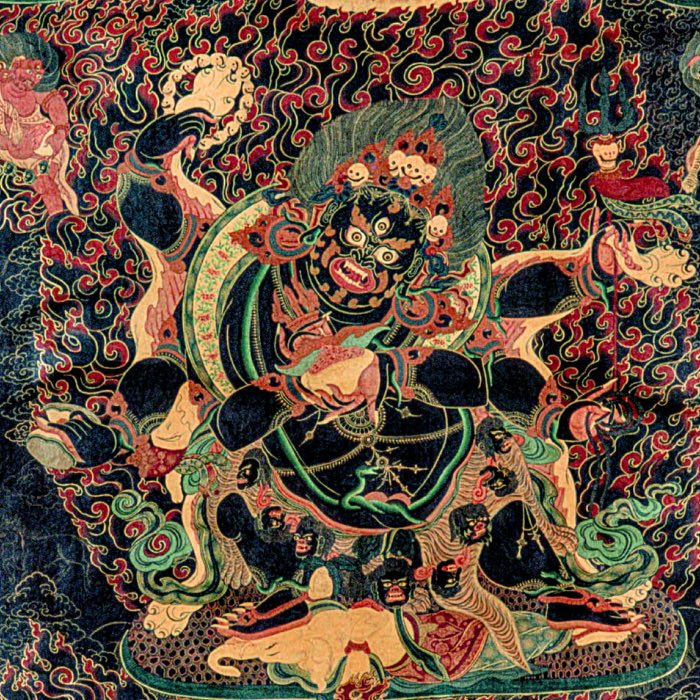

The subjects of these tattoos often included mythical creatures like oni (demons), dragons, and Buddhist symbols, as well as natural elements like flowers and animals. While there is some debate about who originally wore these tattoos, it is generally believed that they were popular among the lower classes, including laborers, firemen, and courtesans, who sought to express their individuality and bravery. Some scholars, however, argue that wealthy merchants, who were legally forbidden from displaying their wealth, also embraced these tattoos, hiding them beneath their clothing.

Left: Kirenji Toko, from One of the Eight Hundred Heroes of the Water Margin of Japan, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1830-1832. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ/The British Museumꜛ (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). – Right: Tengan Isobei, from One of the Eight Hundred Heroes of the Water Margin of Japan, ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1830-1832. Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ/The British Museumꜛ (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Horimono gained particular popularity among the middle class. The reasons for this are complex, but one theory suggests that the rise of the merchant class in Edo led to a desire for self-expression and individuality. The merchants, who were legally forbidden from displaying their wealth, including wearing luxurious kimonos, used full-body tattoos as a form of “hidden kimono”, allowing them to showcase their opulence and taste discreetly. These tattoos, often elaborate and detailed, served as a way to express personal wealth and style without violating the strict social norms of the time.

Although the tattoo phenomenon began to spread to the middle class towards the beginning of the 19th century, it never achieved the same widespread acceptance as it did among the lower classes. Nonetheless, the intricate designs and the cultural significance of horimono during the Edo period left a lasting legacy on Japanese tattooing, one that continues to influence the art form today.

The Meiji Restoration: Tattoos and modernity

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 brought profound changes to Japan, as the country sought to modernize and adopt Western practices. In this new era, tattoos were increasingly seen as a barbaric relic of the past. In an effort to present a more civilized image to the West, the Meiji government officially banned tattooing in 1872. This prohibition, however, only drove the practice underground.

Hand-colored photograph by Hori Kasiwa from the 1890s, showing a horimono from the Meiji era. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Despite the official ban, Japanese tattoo artists continued to ply their trade, finding new clients among foreign sailors and travelers who were fascinated by the art of traditional Japanese tattooing. These sailors carried their irezumis back to the West, helping to spread Japanese tattoo art internationally.

The ban on tattooing remained in place until 1948, when it was lifted by the American occupation forces after World War II. However, by this time, tattoos had become deeply associated with the yakuza — Japan’s notorious organized crime syndicates. The stigma surrounding tattoos, particularly large body tattoos, persisted, and many public places in Japan, such as hot springs and gyms, continued to ban people with visible tattoos.

Modern Japanese tattooing: Tradition meets contemporary trends

In modern Japan, tattooing occupies a complex and often contradictory position. While some younger Japanese view tattoos as trendy or fashionable, the majority of the population still associates them with the yakuza or considers them a marker of lower-class status. This stigma can make it difficult for tattooed individuals to access certain public facilities or find employment in traditional sectors.

In the short documentary “Art of Shame Short”, Japanese tattoo artist discuss the stigma associated with tattoos in modern Japan. Source: YouTubeꜛ.

Despite these challenges, the art of Japanese tattooing has continued to thrive, attracting both domestic and international clients. Contemporary Japanese tattoo artists are known for their exceptional skill and adherence to traditional techniques, even as they incorporate modern styles and technologies. Horimono remains a highly respected and sought-after form of body art, known for its intricate designs and deep cultural significance.

Sanja Matsuri Festival in Tokyo is a rare occurrence, where traditional horimono are shown in public space. Photograph by Kan Phongjaroenwit (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Sanja Matsuri Festival in Tokyo is a rare occurrence, where traditional horimono are shown in public space. Photograph by Kan Phongjaroenwit (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Traditional horimono is still practiced by specialized tattoo artists, many of whom work in relative obscurity. These artists continue to use the traditional tebori (hand-poked) method, which involves manually inserting the ink into the skin using a set of needles attached to a wooden handle. This method is time-consuming, painful, and expensive, with full-body tattoos taking years to complete. The process is also highly formalized, with the artist often guiding the design and execution of the tattoo rather than simply following the client’s wishes.

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horimono example, photographed by Jeff Laitila (flickr)ꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Horiyoshi III (born as Yoshihito Nakano in 1946) is a renowned horimono master (horishi) living in Yokohama, Japan. He is known for his traditional full-body tattoos and has been practicing the art of horimono for over 40 years. Apart from tattooing, Horiyoshi III also publishes books and founded, together with his wife, Japan’s only tattoo museum in Yokoahama.Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Chōyūkai: A preservation of horimono traditions

Amidst the complex perceptions of horimono in modern Japan, there exists a community that upholds the tradition of tattooing as a revered cultural practice. The Chōyūkai, a group formed over a century ago and featured in a recent Vice articleꜛ, is composed of individuals who share a common bond: their bodies are adorned with traditional full-body horimono tattoos. Contrary to common misconceptions, the Chōyūkai is not a group associated with crime; in fact, they have a strict rule prohibiting members from being involved in organized crime. Their membership spans various professions and backgrounds, unified by their respect for the art of horimono.

Edo Choyukai 江戸彫勇会 (Members of the Choyukai of Edo), ukiyo-e print by Yamamoto Hisashi, 1957. Source: The British Museumꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Edo Choyukai 江戸彫勇会 (Members of the Choyukai of Edo), ukiyo-e print by Yamamoto Hisashi, 1957. Source: The British Museumꜛ (license: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The Chōyūkai don’t view their tattoos as a marker of criminality, but as an important aspect of their cultural identity. The tattoos are seen as symbols of protection, bravery, and commitment to their heritage. In Edo period, firemen and working class physical laborers often chose to have tattoo motifs from traditional Japanese folktales and Buddhist mantras, as they believed that these tattoos would protect them from harm from their dangerous work hazards and bring good fortune.

Tattoos under Waterfall, from the series Edo Jidai Horimono Zoroi (List of Tattoos in Edo Era), ukiyo-e by an unknown artist, 1890-1900. A group of tattooed men, probably firemen, are performing a type of cleansing ritual and spiritual training under the waterfall.Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ (license: public domain).

Tattoos under Waterfall, from the series Edo Jidai Horimono Zoroi (List of Tattoos in Edo Era), ukiyo-e by an unknown artist, 1890-1900. A group of tattooed men, probably firemen, are performing a type of cleansing ritual and spiritual training under the waterfall.Source: ukiyo-e.orgꜛ (license: public domain).

The community gathers annually for a pilgrimage to Mt. Oyamaꜛ in Kanagawa Prefecture, a journey that has been part of their tradition since the group’s inception. The pilgrimage is a significant cultural event for the Chōyūkai. It begins with a waterfall purification ritual called takigyō, where members cleanse themselves in the cold waters, symbolically purifying their spirits and preparing for the sacred journey ahead. This ritual is deeply rooted in Shinto practices, reflecting the group’s reverence for nature and tradition as well as the spirituality practiced.

Ōyama-Afuri Shrine at Mount Ōyama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Ōyama-Afuri Shrine at Mount Ōyama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

As the group ascends Mt. Oyama, they engage in a blend of reverence and camaraderie. While the pilgrimage includes moments of serious reflection and ritual, it is also a time for the members to connect, share memories, and enjoy each other’s company. The climb is physically demanding, and the participants often strip down to reveal their intricate tattoos, which are normally kept hidden from public view throughout the year.

Chōyūkai pilgrimage. Screenshot from the Vice documentary movie “The Japanese Pilgrimage Where Horimono Tattoos Are Revered”ꜛ.

Chōyūkai pilgrimage. Screenshot from the Vice documentary movie “The Japanese Pilgrimage Where Horimono Tattoos Are Revered”ꜛ.

The climax of the pilgrimage occurs at the Oyama Afuri Shrine, where the Chōyūkai members present their tattoos to the gods during a blessing ceremony conducted by a Shinto priest. This ritual is not only an offering of respect but also a moment of pride, as the participants honor the artistry and cultural heritage embodied in their horimono. The ceremony is followed by a communal feast, known as naorai, where the pilgrims dine and drink sake in the company of gods and spirits, celebrating the successful completion of their journey.

The waterfall purification called takigyō. Screenshot from the Vice documentary movie “The Japanese Pilgrimage Where Horimono Tattoos Are Revered”ꜛ.

The waterfall purification called takigyō. Screenshot from the Vice documentary movie “The Japanese Pilgrimage Where Horimono Tattoos Are Revered”ꜛ.

The Chōyūkai pilgrimage serves as a powerful reminder that horimono is not merely a symbol of rebellion or crime; it is a cherished tradition that has been preserved through generations. In the town of Oyama, where the pilgrimage is an annual event, the local community views these tattooed men not with fear, but with respect. The exposure to this tradition has led to a more accepting attitude towards horimono, in contrast to the general stigma that persists in other parts of Japan.

For the members of the Chōyūkai, their tattoos are not for public display or societal approval; they are deeply personal expressions of their beliefs, values, and connection to a cultural tradition that transcends the negative stereotypes often associated with Japanese tattoos. The pilgrimage is a testament and a reminder to the enduring significance of horimono as a living cultural practice.

The Vice article also features a documentary filmꜛ, which offers further insights into the Chōyūkai and their annual pilgrimage, and is well worth watching to gain a deeper understanding of this unique tradition.

Vice documentary movie “The Japanese Pilgrimage Where Horimono Tattoos Are Revered” on YouTubeꜛ.

Conclusion

Horimono has a rich history that weaves together elements of spirituality, art, social status, and defiance. From its ancient origins to its complex role in modern Japanese society, tattooing in Japan reflects the country’s evolving attitudes toward tradition, modernity, and self-expression. Horimono and ukiyo-e are deeply interconnected and have influenced each other. The popularity of ukiyo-e woodblock prints depicting tattooed heroes helped fuel the demand for decorative tattoos, while tattoo artists drew inspiration from the bold lines and vibrant colors of ukiyo-e prints. In both art forms, the craftsmanship consists of ‘carving’ or ‘engraving’ intricate designs onto a surface, whether it be paper or skin. Ukiyo-e declined by the late 19th century, but its legacy lives on in the art of horimono, which continues to captivate audiences around the world.

Today, as Japanese tattoo artists continue to blend the old with the new, the legacy of horimono endures, celebrated both for its artistic beauty and its deep cultural roots. Eventhough the stigma surrounding tattoos persists in Japan, the art of horimono remains a powerful symbol of tradition, craftsmanship, and individuality, embodying the spirit of the floating world that inspired its creation.

References and further reading

- Sandy Fellman, The Japanese Tattoo, 1987, ISBN: 0896597989

- Okazaki, M: Wabori, Traditional Japanese Tattoo: Classic Japanese Tattoos from the Masters, 2013, ISBN: 9881250749

- Brian Ashcraft, Hori Benny, Japanese Tattoos - History, Culture, Design (2016), 2016, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 9784805313510

- Yori Moriarty, Japanese Tattoos - Meanings, Shapes And Motifs, 2018, Promopress, ISBN: 9788416851966

- Takahiro Kitamura, Katie M. Kitamura, Tattoos Of The Floating World - Ukiyo-e Motifs In The Japanese Tattoo, 2003, Kit Pub, ISBN: 9789074822459

- Masato Sudo, Ransho: The World of Horiyoshi III – The World of Horiyoshi Sandaime, 2018, Shogakukan, ISBN: 9784096822074

- Donald Richie, Ian Buruma, The Japanese Tattoo, 1989, Weatherhill, Incorporated, ISBN: 9780834802285

- Takahiro Kitamura, Katie M. Kitamura, Bushido - Legacies Of The Japanese Tattoo, 2000, Schiffer Publishing, ISBN: 9780764312014

- Martin Hladik, Traditional tattoo in Japan – HORIKAZU: Lifework of the tattoo master from Asakusa in Tokio, 2012, Edition Reuss Germany, ISBN: 9783943105100

- Jill Horiyuki Mandelbaum, Studying Horiyoshi III: A Westerner’s Journey Into Japanese Tattoo, 2008, Schiffer Publishing, ISBN: 978-0764329685

- Vice articleꜛ and documentary movie “The Japanese Pilgrimage Where Horimono Tattoos Are Revered”ꜛ

- Vice documentary movie “An Inside Look at Hand-Poked Japanese Tattoos”ꜛ

- pen article “The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period”ꜛ

- “Art of Shame Short”, a short documentary on the stigma associated with tattoos in Japanꜛ

comments