Tsukioka Yoshitoshi: The last great master of ukiyo-e

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) is celebrated as the last great master of ukiyo-e. His works are characterized by a unique blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and modern influences, reflecting the tumultuous period of the Meiji Restoration. Yoshitoshi’s prints are known for their vivid colors, dynamic compositions, and expressive depictions of historical and supernatural subjects. In this post, we will explore the life and art of this influential artist, and examine some of his most famous works.

Fujiwara no Yasumasa Gekka Roteki zu (Fujiwara no Yasumasa Playing the Flute), triptych, 1883. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Fujiwara no Yasumasa Gekka Roteki zu (Fujiwara no Yasumasa Playing the Flute), triptych, 1883. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Biography

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡 芳年), born Owariya Yonejiro in 1839 in Edo (now Tokyo), Japan, is widely regarded as the last great master of the ukiyo-e tradition. Yoshitoshi’s work is noted for its intense emotional depth, dramatic compositions, and innovative use of color and line. He is particularly famous for his exploration of themes such as the supernatural, violence, and the human psyche, making his prints some of the most striking and memorable in the history of Japanese art.

Early life and training

Yoshitoshi was born into a merchant family during a time of significant social and political upheaval in Japan. The final years of the Tokugawa shogunate were marked by instability, and Japan was on the brink of major transformations as it moved toward the Meiji Restoration. These changes would later influence Yoshitoshi’s work, as he witnessed firsthand the impact of modernization on traditional Japanese society.

At the age of 11, Yoshitoshi was apprenticed to Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the leading ukiyo-e artists of the time and a master known for his dynamic warrior prints and depictions of folklore and mythology. Under Kuniyoshi’s guidance, Yoshitoshi developed his skills in drawing and woodblock printing, quickly becoming proficient in the techniques of the ukiyo-e tradition. Kuniyoshi’s influence is evident in Yoshitoshi’s early work, which often featured dramatic and violent imagery, a reflection of his mentor’s style.

Yoshitoshi’s apprenticeship was cut short by the death of Kuniyoshi in 1861. Despite this loss, Yoshitoshi continued to work independently, producing prints that showcased his growing interest in psychological and emotional themes.

Struggles and artistic development

The 1860s and 1870s were challenging years for Yoshitoshi. The ukiyo-e industry was in decline due to the rise of photography and the influx of Western art, which led to reduced demand for traditional woodblock prints. Yoshitoshi also faced personal difficulties, including financial hardship and bouts of mental illness. These struggles were reflected in his work, which often depicted scenes of violence, suffering, and the darker aspects of the human experience.

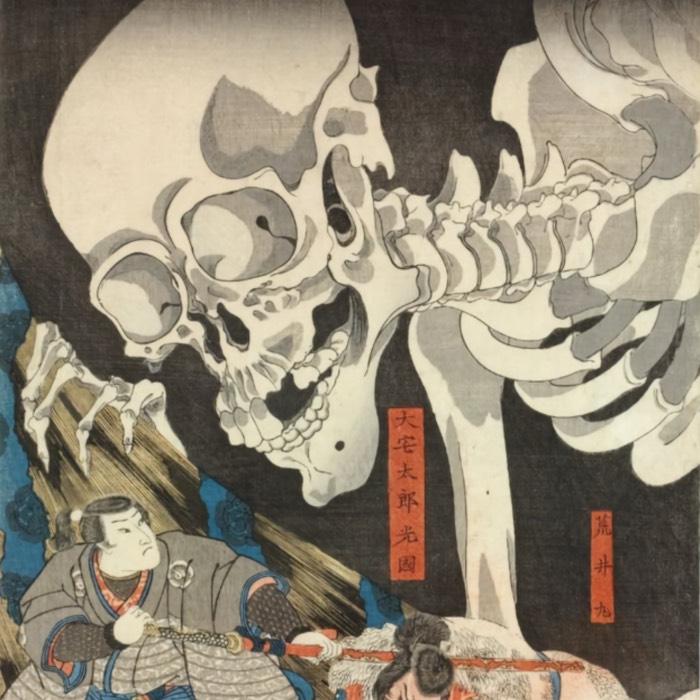

The Lonely House on Adachi Moor, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Despite these challenges, Yoshitoshi’s work began to gain recognition for its originality and emotional intensity. His prints from this period are marked by bold compositions, dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, and a deep exploration of the human condition. One of his most famous series from this time is Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verse (Eimei Nijūhasshūku), which graphically depicted scenes of violence and horror, earning Yoshitoshi both acclaim and notoriety.

Artistic maturity and success

By the 1880s, Yoshitoshi had overcome many of his personal and professional difficulties, entering a period of artistic maturity and success. His work became more refined, with a greater emphasis on color, composition, and psychological depth. During this time, he produced some of his most celebrated series, including One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi) and New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (Shinkei Sanjūrokkaisen).

These series marked a shift in Yoshitoshi’s style, as he moved away from the graphic violence of his earlier work to focus on more subtle and complex themes. His prints from this period often depicted historical and legendary figures, exploring themes of heroism, spirituality, and the supernatural. Yoshitoshi’s use of color became more sophisticated, and his compositions more intricate, reflecting his deepening mastery of the ukiyo-e form.

Yoshitoshi’s success in the 1880s also led to a revival of interest in ukiyo-e, as his innovative approach breathed new life into a declining art form. He became one of the most respected and influential artists of his time, with a large following of students and admirers.

Later years and legacy

In the final years of his life, Yoshitoshi continued to produce powerful and evocative works, despite ongoing struggles with mental illness. His later work reflects a sense of introspection and melancholy, as well as a continued fascination with the mysteries of the human mind and spirit.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi passed away in 1892 at the age of 53, leaving behind a legacy as one of the most important and innovative ukiyo-e artists. His work has had a lasting impact on both Japanese and Western art, influencing generations of artists and continuing to captivate audiences with its emotional depth and artistic brilliance.

Style and significance

Exploration of psychological and supernatural themes

Yoshitoshi is perhaps best known for his exploration of psychological and supernatural themes. His work delves into the darker aspects of human experience, including violence, madness, and the supernatural, reflecting his own struggles with mental illness and the turbulent times in which he lived.

Yoshitoshi’s prints often feature ghosts, demons, and other supernatural beings, depicted with a sense of realism and intensity that sets them apart from earlier ukiyo-e depictions of the supernatural. His series New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts is particularly renowned for its eerie and atmospheric portrayals of ghostly apparitions.

Yoshitoshi did not shy away from depicting scenes of violence and suffering, often in graphic detail. His series Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verse is a prime example of this, showcasing his ability to convey the horror and emotional impact of violence.

Beyond the graphic content, Yoshitoshi’s work is marked by a deep psychological complexity. His prints often explore the inner lives of his subjects, capturing their emotions, fears, and desires with a level of nuance that was unusual for the time.

Mastery of color and composition

Yoshitoshi was a master of color and composition, using these elements to enhance the emotional impact of his work. His prints are characterized by their bold use of color, dramatic contrasts, and intricate compositions.

Left: Eimei nijūhasshūku from, Twenty-eight famous murders with verse, 1867. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Tokaido Meisho no Uchi, 1863. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Yoshitoshi’s use of color evolved over his career, with his later work characterized by a more subtle and sophisticated palette. He often used color to convey mood and atmosphere, with deep reds, blues, and blacks creating a sense of tension and drama. His compositions are often complex and layered, drawing the viewer’s eye across the image to uncover hidden details and meanings. He skillfully used space and perspective to create a sense of depth and movement, adding to the dynamic quality of his prints.

Revival of ukiyo-e

Despite working in a time when ukiyo-e was in decline, Yoshitoshi played a crucial role in reviving interest in the art form. His innovative approach and willingness to tackle challenging and unconventional subjects helped to renew public interest in ukiyo-e, ensuring its survival into the modern era.

Yoshitoshi’s work has had a significant influence on both Japanese and Western art. His exploration of psychological and supernatural themes has resonated with modern artists, and his innovative use of color and composition has inspired new approaches to visual storytelling.

Significance

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s significance lies in his ability to push the boundaries of ukiyo-e, both in terms of subject matter and technique. His work reflects the complexities of the human experience, capturing the darker aspects of life with honesty and emotional depth. At the same time, his prints are celebrated for their artistic beauty and technical skill, making him one of the most important figures in the history of Japanese art.

Notable works

Yoshitoshi produced many significant and influential works throughout his career. Here is a list of his print series, organized by decade:

1850ies

- Battle of Cats and Mice (Byōso kassen), 1859

1860ies

- Tale of the Forty-Seven Rōnin (Kanadehon chūshingura), 1860

- Modern Celebrities of the East (Imayō hiiki azuma-e), 1860

- Famous Places of the Tokaido (Tōkaidō meisho no uchi), 1863

- Modern ‘Journey to the West’ (Tsūzoku saiyūki), 1864-1865

- One Hundred Ghost Stories of China and Japan (Wakan hyaku monogatari), 1865

- Fan Tokaido (Suehiro goju-san tsugi), 1865

- Celebration of Gallantry (Isami no kotobuki), 1865

- Biographies of Modern Men (Kinsei kyōgiden), 1865-1866

- Famous Fights Between Brave Men (Eimei kumiuchi zoroi), 1865-1866

- Handsome and Brave Heroes of the Suikoden (Biyū suikoden)

- Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verse (Eimei nijūhasshūku), 1866-1869 – This series graphically depicts scenes of violence and murder, accompanied by verses that add to the dramatic and emotional impact of each print. The series is one of Yoshitoshi’s most controversial and is known for its unflinching portrayal of brutality.

- Eight Views from Fine Tales of Warriors (Bidan musha hakkei), 1867-1868

- Tales of the Floating World on Eastern Brocade (Azuma no nishiki ukiyo kōdan), 1867-1868

- Strong Heroes of the Water Margin (Gōketsu suikoden), 1868

- Portraits of True Loyalty and Chivalrous Spirit (Seichū gishinden), 1868

- Selection of One Hundred Warriors (Kaidai hyaku sensō), 1868-1869

- Historical Biographies of the Loyal Retainers (Seichū gishi meimei ga-den), 1869

- Theater Alphabet of True Forms (Shin-zō gekijō iroha ittsui), 1869

1870ies

- Beautiful Women and Fancy Dishes in Tokyo (Tōkyō ryōri sukoburu beppin), 1871

- Biographies of Valiant Drunken Tigers (Keisei suikoden), 1874

- Postal News (Yūbin hōchi shinbun), 1875-1876

- Mirror of Beauties Past and Present (Kokon hime kagami), 1875 or 1876

- Mirror of Famous Generals of Japan (Dai nippon meishō kagami), 1876-1882 – This series honors the famous generals and warriors of Japan’s past, presenting them in dynamic and powerful compositions. The prints highlight Yoshitoshi’s skill in depicting historical figures with a sense of grandeur and dignity.

- Barometer of Emotions (Seiu kandankei), 1876-1877

- Firemen’s Standards of all Great Districts (Kaku daiku matoi), 1876 – An examples of Yoshitoshi’s enthusiasm for depicting the firemen of Edo as heroes.

- Collection of Desires (Mitate tai zukushi), 1877-1878

- Specialties of Restaurants in the Imperial City (Kōto kaiseki beppin kurabe), 1878

- Short Illustrated History of Great Japan (Dai nippon shiryaku zue), 1879-1880

1880ies

- Moral Lessons through Pictures of Good and Evil (Kyōkun zenaku zukai), 1880

- Pride of Tokyo’s Twelve Months (Tōkyō jiman juni kagetsu), 1880

- Twenty-Four Hours at Shinbashi and Yanagibashi (Shinryū nijūshi toki), 1880

- Crazy Pictures of Famous Places in Tokyo (Tōkyō kaika kyōga meishō), 1881

- Twenty-four Accomplishments in Imperial Japan (Kōkoku nijūshikō), 1881-1887

- Sketches by Yoshitoshi (Yoshitoshi ryakuga), 1882

- Four Seasons at their Height (Zensei shiki), 1883

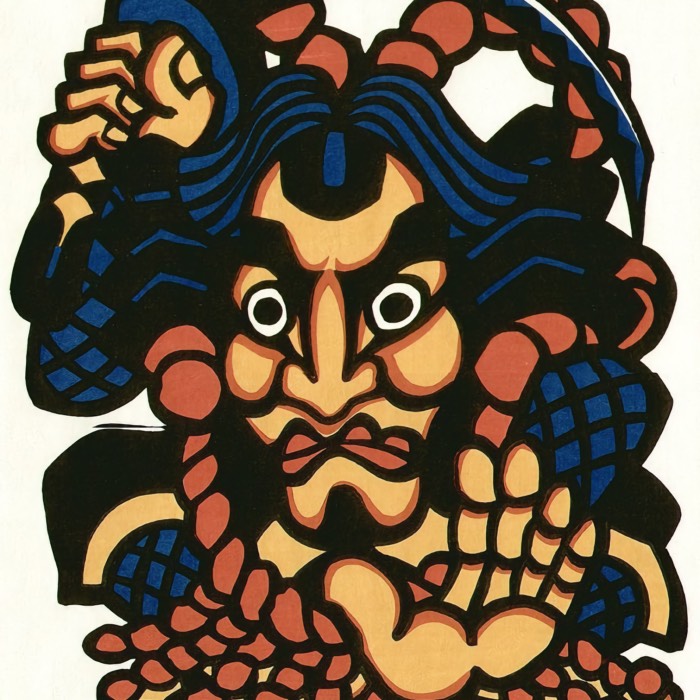

- Courageous Warriors (Yoshitoshi musha burui), 1883-1886

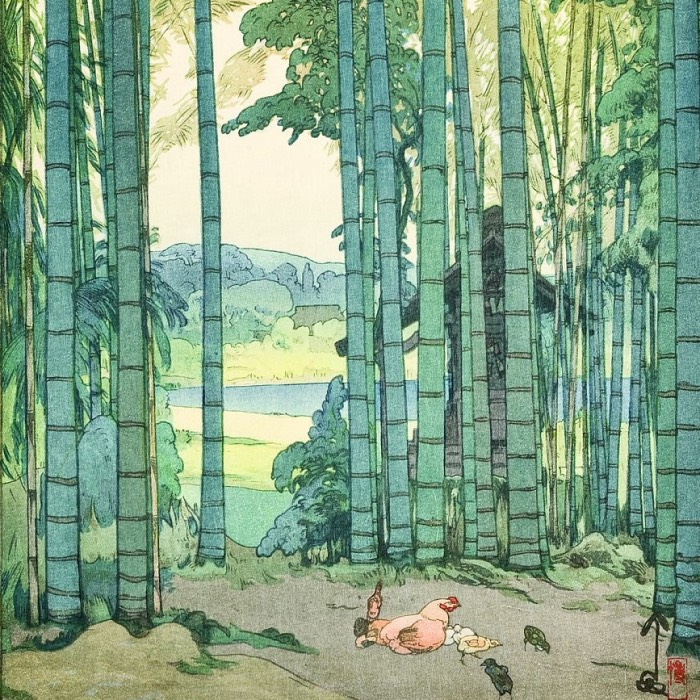

- One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi), 1885-1892 – One of Yoshitoshi’s most famous and revered series. It explores various themes, including historical events, legends, and the supernatural, all linked by the motif of the moon.

- Personalities of Recent Times (Kinsei jimbutsu shi), 1886-1888

- Thirty-Two Aspects of Women (Fūzoku sanjūnisō), 1888

1890ies

- Actors with Snow, Moon and Flowers (Yakusha setsugekka), 1890

- Thirty-six New Forms of Ghosts, 1839-1892 – This series features ghostly and supernatural themes, with each print depicting a different story or legend involving spirits and otherworldly beings. The series is known for its eerie atmosphere and imaginative compositions.

- heroes (Oshu adachigahara hitotsuya no zu), 1885

Examples

Left: Benkei Calming the Waves at Daimotsu Bay, from Tsuki hyakushi, One hundred aspects of the moon), 1886. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Warriors Trembling with Courage: The fight between Ushiwakamaru (Minamoto no Yoshitune) and the bandit chief Kumasaka Chohan in 1174, 1883. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Gravemarker Moon, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1887. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The moon through a crumbling window, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1887. Depicted is the Indian Bodhidharma, who brought of Chan Buddhism to China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Seiriki Tamigorō committing suicide from Kinsei kyōgiden, 1865. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moon and Smoke (Enchu no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1892. The picture shows a firefighter. Firefighters were celebrated as heroes in Edo as the city’s buildings were predominantly made of wood and devastating fires often broke out. The character on the back of this jacket reads matoi, indicating that this is the standard bearer for the brigade fighting the fire in the foreground. Standards were held aloft on roof tops so that each brigade could be identified and so that firemen could signal above the flames and noise. The character on the hat shows that he belongs to Number One Company. A distant fireman holds another standard on the roof opposite. There was great rivalry between the district brigades because the particular brigade that saved each property was rewarded. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Cassia-tree moon (Tsuki no katsura), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1892. This scene depicts the Chinese Daoist master Wu Gang with his axe. For abusing his power, he had been punished by the gods to forever chop the cassia trees on the Moon, but they immediately regenerate themselves. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Lady Gosechi (Gosechi no myobu), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1892. A scene from Jikkinshō (十訓抄) depicts Minamoto no Tsunenobu and others who are moved to tears by the sound of a koto played by a former court lady who has abandoned the world to live in seclusion in a dilapidated house. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Emperor Jimmu, from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1880. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Roku Son’ō Tsunemoto (also known as Minamoto no Tsunemoto), from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1879. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Minamoto no Yoshiie, from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1876. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Minamoto no Yoshimitsu Instructing Toyohara no Tokiaki in Music, from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1879. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Minamoto no Yoritomo and his retainers releasing cranes to mourn for the war dead in the Mutsu and Dewa Conquest, from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1879. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Saimyō-ji Tokiyori (also known as Hōjō Tokiyori), from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1880. Lay Priest Tokiyori of Saimyō-ji Temple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Kusunoki Masashige reading to his troops at the temple Shitennoji, from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1878. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Mori Motonari attacking Sue Harutaka at Itsukushima, from the series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (Dai nihon meishô kagami), 1880. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Warriors Trembling with Courage: Gosho no Gorōmaru captures Soga Tokimune, from Revenge of the Soga Brothers, 1886. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Lord Sadanobu threatens a demon in the palace at night, from New Forms of the Thirty-six Ghosts Prints, 1889. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Encountering a demon, from New Forms of the Thirty-six Ghosts Prints, 1889. Omori Hikoshichi carrying a woman across a river; as he does so, he sees that she has horns in her reflection. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Killing of a Nue, from New Forms of the Thirty-six Ghosts Prints, 1889. : Ii no Hayata killing a Nue at the imperial palace. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Rising moon over Mount Nanping (Nanpeizan shogetsu), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The Gion District (Gionmachi), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Woman watching the shadow of a pine branch cast by the Moon, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The village of the Shi clan on a moonlit night (Shikason tsukiyo), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Depicted is Shi Jin, featuring the Nine-Dragon tattoo from The Water Margin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Inaba Mountain moon (Inabayama no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. The young Toyotomi Hideyoshi leads a small group assaulting the castle on Inaba Mountain (The Siege of Inabayama Castle). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Mountain moon after rain (Ugo no sangetsu), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Soga Tokimune viewing a moonlit mountain after rainfall. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon of pure snow at Asano River (Asanogawa seisetsu no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Chikako was the daughter of Zeniya Gohei who was wrongfully imprisoned. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Cooling off at Shijo (Shijo noryo), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The cry of the fox, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Hakuzōsu is the kitsune who pretended to be the Buddhist priest. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Tsunenobu and the demon, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. The scene depicts a story where the courtier Minamoto no Tsunenobu was watching the autumn moon and composed the following verse based on Tang dynasty poetry: ‘I Listen to the Sound of the Cloth Being Pounded/ As the Moon Shines Serenely/ And Believe that There is Someone Else/ Who Has Not Yet Gone to Sleep.’ Whereupon, a massive demon appeared and replied with a poetic verse from Li Bai: ‘In the northern sky, geese fly across the Big Dipper; to the south, cold robes are pounded under the moonlight.’ Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Mount Yoshino midnight-moon (Yoshinoyama yowa no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Against the advice of his general Masashige, Emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339) was encouraged by courtier Sasaki Kiyotaka, for his own political gain, to fight the rebelling forces of Ashikaga Takauji at the battle of Minatogawa in 1336. As a result of losing the battle, Masashige committed suicide and the Emperor fled to Mount Yoshino, where Kiyotaka was also forced to commit suicide. Kiyotaka’s ghost haunted and harried the exiled courtiers, none of whom dared to face it. Finally it was confronted by Masashige’s daughter-in-law, the heroic Iga no Tsubone, who drove it away. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The moon of Ogurusu in Yamashiro (Yamashiro Ogurusu no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Featuring Akechi Mitsuhide. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Suzaku Gate moon (Suzakumon no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Hakuga Sammi is the Chinese reading of the name and court rank of Minamoto no Hiromasa (918-80), grandson of Emperor Daigo. He was a famous musician, equally adept at playing a variety of wind and string instruments. We see him here from the rear, wearing the robes and lacquered hat of a Heian courtier, and playing the yokobue, a transverse flute. He is outside the Suzaku Gate of the Daidairi enclosure in Kyoto, which contained the imperial palace and government offices. The identity of his companion is uncertain, but judging from his hat and beard he is probably a foreigner. Hiromasa’s skill on the flute was legendary and the beauty of his playing is recounted in numerous tales. One of them tells of him being robbed of all his possessions except a wooden flute (hichiriki). When he picked up the remaining flute and started to play, the sound carried through the streets to the ears of the robbers. They were so moved by its beauty that they repented their crime and returned Hiromasa’s possessions.Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Itsukushima moon (Itsukushima no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. A scene from The Tale of the Heike in which Taira no Kiyomori meets a prostitute composing waka poems on a small boat during his pilgrimage to Itsukushima Shrine. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Faith in the third-day moon (Shinko no mikazuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moon of the pleasure quarters (i.e., Yoshiwara) (Kuruwa no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon at the Yamaki Mansion (Yamaki yakata no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Kato Kagekado tries to kill Yamaki Kanetaka using his helmet as bait in the Battle of Ishibashiyama. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Chikubushima moon (Chikubushima no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Yugao chapter from The Tale of Genji (Genji yugao maki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Shown is the ghost of the most mysterious of Prince Genji’s lovers in The Tale of Genji, the 11th-century classic by Murasaki Shikibu. In Chapter 4, Genji is on the way to visit his old nurse when he is attracted by the white flowers of a gourd overrunning the garden of a dilapidated house. He asks a servant to fetch a bloom and it is returned on a fan inscribed with a poem referring to his ‘evening face’, the literal meaning of yūgao, the name of the flower (lagenaria siceraria). He courts the mysterious author of the poem, and takes her to a nearby villa, where she is visited in the middle of the night by the jealous spirit of one of Genji’s lovers; she breaks into a fever and within hours she is dead. Genji is overcome with grief and years later still longed for a further glimpse of the woman who faded as quickly as the white flowers in her garden. The print shows her ghost floating through her garden on the night of a full moon. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Mount Ji Ming moon (Keimeizan no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Kitayama moon (Kitayama no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Toyohara no Muneaki (ja), a master instrumentalist, blows his shō to escape the wolves. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Dawn moon of the Shinto rites (Shinji no zangetsu), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Mount Otowa moon (Otowayama no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. The spirit of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro appears at the Kiyomizu-dera. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Takakura moon (Takakura no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Hasebe Nobutsura watches as Prince Mochihito, disguised as a woman, leaves to escape his Taira clan pursuers. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Moon of the Milky Way (Ginga no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. This scene depicts the star-crossed lovers of the Qixi Festival in China, and the Tanabata festival in Japan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moon over the pine forest of Mio, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Takeda Shingen during his invasion of Suruga Province. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon of the enemy’s lair (Zokuso no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Yamato Takeru disguised himself as a girl to assassinate the brothers of the Kumaso leader. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Sumiyoshi full moon (Sumiyoshi no meigetsu), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Reading by the moon (Dokusho no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moon of Enlightenment (Godo no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. This scene depicts one of the Seven Luck Gods, Hotei, pointing at the Moon, in reference to Zen aphorism how pointing at the Moon is not the Moon itself. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Katada Bay moon (Katadaura no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Saitō Toshimitsu, who fled after being defeated at the Battle of Yamazaki. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Shizu Peak moon (Shizugatake no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Toyotomi Hideyoshi at the Battle of Shizugatake. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Joganden moon (Joganden no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Minamoto no Tsunemoto kills a sika deer that sneaks into the court with his yumi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Hidetsugu in exile, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Toyotomi Hidetsugu was imprisoned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in Mount Kōya. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon of the filial Son (Koshi no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moon of the Red Cliffs (Sekiheki no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Akashi Gidayu writing his death poem before committing Seppuku, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Akashi Gidayu was a retainer to Akechi Mitsuhide, who followed him in death, but not before writing his death poem. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Cloth-beating moon (Kinuta no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. A scene from the Noh play Kinuta. It depicts the sadness of a wife who protects her husband’s house while he is away. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon of the Lonely House (Hitotsuya no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Legend of onibaba who lives in Asajigahara. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Rendezvous by moonlight, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon of Kintoki’s mountain (Kintokiyama no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: A country couple enjoys the moonlight with their infant son, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. A man and a woman cool off for the evening under a trellis of calabash. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Musashi plain moon (Musashino no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Monkey-music moon (Sarugaku no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The moon’s invention (Tsuki no hatsumei), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Chofu village moon (Chofu sato no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The moon and the abandoned old woman (Obasute no tsuki), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The moon’s four strings (Tsuki no yotsu no o), from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. This scene depicts the famous poet and musician, Semimaru, tuning the strings of his lute at a mountain cottage. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Farmers celebrating the autumn moon, from One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1885. The haiku poet, Matsuo Basho, is said to have come upon two farmers celebrating the full moon. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

A courtesan sees herself reflected in the mirror as a skeleton: two demons look on, 1870s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

A Picture of the News from Kagoshima- Attack at School. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

A Picture of the News from Kagoshima- Attack at School. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Two images from Ban Danemon Naoyuki Conquers the Old Badger at Fukushima’s Mansion, 1866. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ and Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Battle before Kumamoto Castle, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Battle before Kumamoto Castle, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Battle before Kumamoto Castle, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Battle before Kumamoto Castle, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Carp with Wisteria, 1889. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Carp with Wisteria, 1889. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Chosen daihyoutei, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Chosen daihyoutei, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Geisha Accompanying Dancing Measles with Samisen, 1862. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Detail from Narihira and Nijo no Tsubone at the Fuji River, 1882. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

*Celebrating the New Year *, 1860. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

*Celebrating the New Year *, 1860. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kato Kiyomasa hunting tigers in Korea during the Imjim war, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kato Kiyomasa hunting tigers in Korea during the Imjim war, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Gikeiki Gojobashi no zu, Gojo Bridge, an Episode from the Life of Yoshitsune, 1881. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Gikeiki Gojobashi no zu, Gojo Bridge, an Episode from the Life of Yoshitsune, 1881. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Fudo Threatening Yuten with His Sword, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Fudo Threatening Yuten with His Sword, 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

triptych from Heroes and the Five Elements, 1867. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

triptych from Heroes and the Five Elements, 1867. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Shiei Riding a Carp over the Sea, from Sketches by Yoshitoshi, 1882. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Shiei Riding a Carp over the Sea, from Sketches by Yoshitoshi, 1882. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Taira No Kiyomori Seeing Skulls in the Snowy Garden, from A New Selection of Strange Events, 1882. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Taira No Kiyomori Seeing Skulls in the Snowy Garden, from A New Selection of Strange Events, 1882. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

triptych from Famous Places in the East Prints, 1883. The Ancient Incident of Umewaka and the Child Seller beside the Sumida River. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

triptych from Famous Places in the East Prints, 1883. The Ancient Incident of Umewaka and the Child Seller beside the Sumida River. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

From Chronicles of the Conquest of Kagoshima in Satsuma Province, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

From Chronicles of the Conquest of Kagoshima in Satsuma Province, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Susanoo slaying the Yamata no Orochi, from the Nihon-Ryakushi: Susanoo-no-Mikoto, 1887. The legendary sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi came from the tail of Yamata no Orochi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Susanoo slaying the Yamata no Orochi, from the Nihon-Ryakushi: Susanoo-no-Mikoto, 1887. The legendary sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi came from the tail of Yamata no Orochi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Fever, triptych depicting Kiyomori, suffering from fever, as he confronts Enma, the king of hell, and the ghosts of Kiyomori’s victims. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Fever, triptych depicting Kiyomori, suffering from fever, as he confronts Enma, the king of hell, and the ghosts of Kiyomori’s victims. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Saigo Takamori and two vassals at night in a boat at sea, watching lightning strike a Western fleet of ships, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Saigo Takamori and two vassals at night in a boat at sea, watching lightning strike a Western fleet of ships, 1877. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Bushu Rokugo funawatashi no zu, 1868. Picture shows the first arrival of Emperor Meiji to Yedo. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Bushu Rokugo funawatashi no zu, 1868. Picture shows the first arrival of Emperor Meiji to Yedo. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: From Nishiki-e (2), 1868. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: From Nishiki-e, 1868. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Conclusion

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi is remembered as the last great master of ukiyo-e, an artist who bridged the gap between traditional Japanese woodblock printing and the emerging modern art of the Meiji era. His work, characterized by its intense emotional depth, innovative use of color and composition, and exploration of psychological and supernatural themes, continues to captivate and inspire. Yoshitoshi’s legacy is one of resilience and creativity, as he transformed personal and societal challenges into some of the most powerful and enduring works in Japanese art.

You can explore a vast collection of Yoshitoshi’s work, e.g., on yoshitoshi.netꜛ or ukiyo-e.orgꜛ.

References and further reading

- yoshitoshi.netꜛ

- Yoshitoshi on ukiyo-e.orgꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Tsukioka Yoshitoshiꜛ

- Woldemar von Seidlitz, Dora Amsden, Ukiyo-e, 2016, Parkstone International, ISBN: 9781785257391

- Amy Reigle Newland, The Hotei encyclopedia of Japanese woodblock prints, 2005, Hotei Publishing, ISBN: 9789074822657

- Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing, 2002, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824825539

- Richard Lane, Masters of the Japanese print, their world and their work, 2021, Hassell Street Press, ISBN: 9781015300231

- Andreas Marks, Japanese Woodblock Prints - Artists, Publishers And Masterworks: 1680 - 1900, 2010, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 9784805310557

comments