Utagawa Kuniyoshi: Master of warriors and fantastic imagery

Our next stop in the world of Japanese woodblock prints takes us to Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), a master of warriors and fantastic imagery. Kuniyoshi was one of the last great masters of the ukiyo-e tradition, known for his dynamic compositions, bold use of color, and imaginative depictions of warriors, monsters, and mythical creatures. In this post, we will explore the life and work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, as well as some of his most famous prints.

The three tiles in Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, c. 1844. This is one of Kunyoshi’s most famous ukiyo-e prints. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The three tiles in Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, c. 1844. This is one of Kunyoshi’s most famous ukiyo-e prints. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Biography

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川 国芳) was born in 1798 in Edo (now Tokyo), Japan, during the late Edo period. He is one of the most celebrated ukiyo-e artists, renowned for his dynamic depictions of legendary heroes, warriors (musha-e), mythical creatures (yūrei-zu), and historical events. Kuniyoshi’s work is characterized by its bold compositions, intricate details, and vivid imagination, making him a key figure in the ukiyo-e tradition and a pivotal artist in the history of Japanese art.

Kuniyoshi self-portrait from the shunga album Chinpen shinkeibai, 1839. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Early life and training

Kuniyoshi was born as Igusa Magosaburō into a modest family of silk dyers. His father was a silk dyer and craftsman, which likely influenced Kuniyoshi’s early interest in color and design. As a child, Kuniyoshi showed a talent for drawing and was apprenticed at the age of 14 to the prominent ukiyo-e master Utagawa Toyokuni I, the head of the Utagawa School, which was known for producing highly skilled artists specializing in actor prints and kabuki scenes (yakusha-e).

Women. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

During his apprenticeship, Kuniyoshi learned the fundamentals of ukiyo-e, including drawing, composition, and woodblock printing techniques. He quickly developed a reputation for his skill in drawing figures and scenes with great dynamism and energy. Toyokuni I recognized Kuniyoshi’s potential and gave him the artist name “Kuniyoshi”, incorporating the characters from his own name, a sign of high regard and respect.

Struggles and breakthrough

Kuniyoshi’s early career was marked by struggles. Despite his evident talent, he initially found it difficult to establish himself in the competitive ukiyo-e market. For several years, he faced financial difficulties and relied on odd jobs to support himself. However, Kuniyoshi’s fortunes changed dramatically in 1827 with the release of his series “The 108 Heroes of the Suikoden” (Tsūzoku Suikoden gōketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori).

From the Suikoden series, 1830. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

This series, based on the popular Chinese novel “Water Margin” (Suikoden in Japanese), depicted the rebellious heroes of the story in dynamic and dramatic poses, often in the midst of battle. The series was an immediate success, catapulting Kuniyoshi to fame and establishing him as a master of warrior prints (musha-e). His vivid portrayals of bravery, loyalty, and martial prowess resonated with the public, particularly in a time when the samurai class was declining, and nostalgia for the ideals of the warrior culture was strong.

Rise to prominence

Following the success of the Suikoden series, Kuniyoshi became one of the most sought-after ukiyo-e artists in Edo. He continued to produce a wide range of works, including more warrior prints, as well as landscapes (fūkei-ga), kabuki actors (yakusha-e), beautiful women (bijin-ga), and satirical images (mitate-e). Kuniyoshi was known for his versatility and ability to adapt his style to suit different genres, which helped him maintain his popularity throughout his career.

View from beneath the Shin Ōhashi Bridgeō (Shin Ōhashi kyōka no chōbō), from *Thirty-six Views of Fuji from the Eastern Capital (Tōto Fuji-mi san-jū-rokkei), c. 1843. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

View from beneath the Shin Ōhashi Bridgeō (Shin Ōhashi kyōka no chōbō), from *Thirty-six Views of Fuji from the Eastern Capital (Tōto Fuji-mi san-jū-rokkei), c. 1843. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Kuniyoshi’s work often reflected his deep interest in history, mythology, and folklore. He had a particular fascination with the supernatural, which is evident in his numerous prints featuring ghosts, demons, and mythical creatures. His imagination knew no bounds, and he frequently pushed the boundaries of ukiyo-e, experimenting with unusual compositions, exaggerated forms, and surreal imagery.

Later years and legacy

In his later years, Kuniyoshi continued to produce innovative and influential works. However, his career was not without challenges. In the 1840s, the Tokugawa shogunate implemented strict censorship laws that restricted the subjects and themes that ukiyo-e artists could depict. These laws made it difficult for Kuniyoshi to continue his usual work, as many of his most popular subjects — such as historical heroes and battles — were now off-limits.

Kajiwara Kagesue, Sasaki Takatsuna, and Hatakeyama Shigetada racing to cross the Uji River before the second battle of Uji during the Genpei War, 1849. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kajiwara Kagesue, Sasaki Takatsuna, and Hatakeyama Shigetada racing to cross the Uji River before the second battle of Uji during the Genpei War, 1849. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Despite these restrictions, Kuniyoshi adapted by incorporating more satirical and allegorical elements into his work, often using humor and subtext to comment on contemporary issues. His ability to navigate the complexities of censorship while maintaining his artistic integrity is a testament to his creativity and resilience.

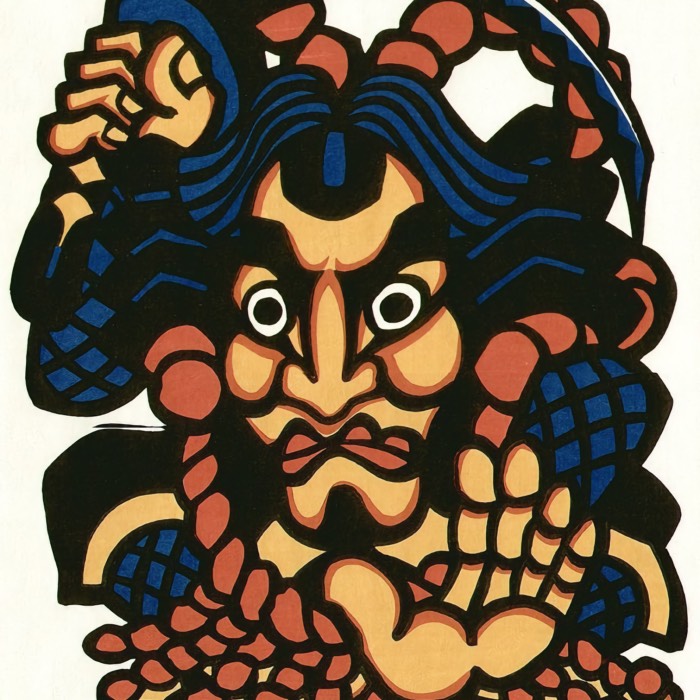

At first glance he looks very fierce, but he is actually a kind person, 1847-1848. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Utagawa Kuniyoshi passed away in 1861, leaving behind a vast and diverse body of work that continues to be celebrated for its artistic excellence and imaginative power. He is regarded as one of the last great masters of ukiyo-e and a pioneer who helped shape the future of Japanese art.

Style and significance

Dynamic composition and dramatic imagery

Kuniyoshi was a master of composition, known for his ability to create dynamic and dramatic scenes that captivated the viewer. His prints often featured bold diagonals, intricate details, and a sense of movement that brought his subjects to life. Whether depicting a fierce battle, a supernatural encounter, or a tranquil landscape, Kuniyoshi’s work was always infused with energy and emotion.

Kuniyoshi’s warrior prints (musha-e) are among his most celebrated works. He depicted legendary heroes and historical figures with exaggerated musculature, fierce expressions, and elaborate armor. His attention to detail in the depiction of weapons, armor, and battle scenes was unmatched, and his ability to convey the intensity of combat made his prints particularly popular.

Honjo Shigenaga parrying an exploding shell. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kuniyoshi had a deep interest in the supernatural and often explored themes of ghosts, demons, and mythical creatures in his work. His yūrei-zu prints in this genre are notable for their eerie atmosphere and imaginative compositions, often blending the grotesque with the fantastical.

Use of color and line

Kuniyoshi’s use of color was bold and striking. He often employed rich, deep tones to create contrast and emphasize the dramatic elements of his compositions. His skillful use of color helped to convey mood and atmosphere, whether it was the ominous gloom of a ghostly encounter or the vibrant energy of a battle scene.

His line work was equally masterful. Kuniyoshi’s lines were strong and expressive, capable of conveying both the physicality of his subjects and the intricate details of their surroundings. His ability to combine precise line work with dynamic compositions made his prints visually compelling and highly impactful.

A Picture of the Flourishing Theater District (Shibaimachi han’ei no zu, from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

A Picture of the Flourishing Theater District (Shibaimachi han’ei no zu, from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Satire and allegory

In response to the censorship laws of the 1840s, Kuniyoshi began incorporating satirical and allegorical elements into his work (mitate-e). He used humor, irony, and symbolism to critique contemporary society and politics, often disguising his commentary within seemingly innocuous scenes. This allowed him to continue expressing his ideas while avoiding direct confrontation with the authorities.

One of Kuniyoshi’s most famous series of satirical works features cats – an animal he was particularly fond of. These prints often depicted cats in humorous or anthropomorphized situations, sometimes serving as subtle allegories for human behavior or political events.

Cats forming the characters for catfish, 1841. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kuniyoshi also created parodies of historical events and famous stories, using them to comment on contemporary issues. These works were often layered with meaning, requiring the viewer to read between the lines to fully appreciate their significance.

Significance

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s significance in the history of ukiyo-e lies in his ability to innovate within the constraints of the genre while remaining deeply connected to its traditions. His work not only reflected the popular tastes of his time but also pushed the boundaries of what ukiyo-e could achieve, both in terms of subject matter and artistic technique.

Kuniyoshi’s influence extended beyond his own time, inspiring future generations of artists both in Japan and abroad. His dynamic compositions and imaginative use of subject matter influenced the development of manga and anime, as well as Western art movements such as Japonisme.

Kuniyoshi’s warrior prints and supernatural themes resonated with the cultural climate of the late Edo period, reflecting the public’s fascination with heroism, mythology, and the supernatural. His work provided a means of escapism during a time of social and political uncertainty, offering viewers a window into worlds of adventure, fantasy, and nostalgia.

Notable works

Utagawa Kuniyoshi produced a vast and diverse body of work throughout his career. Some of his most significant and celebrated pieces include:

- Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest (Kōsō go-ichidai ryaku zu), 1835-1836 – A series of prints depicting the life of the Buddhist monk Nichiren 1222–1282, founder of Nichiren Buddhism in Japan.

- Famous Views of the Eastern Capital (Tōto meisho), 1834 – A series of ten landscape prints portraying people in landscapes of Edo.

- The 108 Heroes of the Suikoden (Tsūzoku Suikoden gōketsu hyaku-hachi-nin no hitori), 1827-1830 – Another series of prints depicting the heroes of the “Water Margin” in dynamic battle scenes.

- Eight Hundred Heroes of Our Country’s Suikoden (Honchō Suikoden gōyū happyaku-nin no hitori), 1830-1836 – Another series of prints based on the Chinese novel “Water Margin”, featuring heroic outlaws in battle.

- Stories of Wise Women and Faithful Wives (Kenjo reppuden), 1841-1842 – A series of prints depicting famous female figures from history and legend.

- Fifty-Three Parallels for the Tōkaidō (1843–1845) – A series of prints inspired by Hiroshige’s “Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō”, featuring humorous and satirical scenes.

- Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety of Our Country (Honchō nijūshi-kō), 1843-1846 – A series of prints illustrating stories of filial piety from Chinese history, written by the Chinese Guo Jujing during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). It recounts the self-sacrificing behavior of twenty-four Chinese children who improved their parents’ lives or peacefully honored their deceased parents.

- Mirror of the Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami), 1844–1846 – A variation of the previous series.

- Untitled set of the six Crystal Rivers, 1847-1848 – A series of prints depicting the six Crystal rivers of Japan.

- Fidelity in Revenge, c. 1848 – Unfortunately, I don’t have any information about this series.

- Seichu Gishi Den (Stories of the True Loyalty of the Faithful Samurai), 1848 – A series of prints depicting scenes from the famous story of the Forty-Seven Ronin.

- The Twenty-four Chinese Paragons of Filial Piety (Morokoshi nijūshi-kō), 1848 – Another series of prints illustrating stories of filial piety from Chinese history.

- The Sixty-nine Post Stations of the Kisokaidō Road (Kisokaidō rokujūku tsugi), 1852-1853 – A series of prints depicting the post stations along the Kisokaidō road, a major highway in Japan.

- Portraits of the Faithful Samurai of True Loyalty (Seichū gishi shōzō), 1852 – Another series of prints depicting the Forty-Seven Ronin.

- The Twenty-Four Generals (Takeda Nijūshi-shō), 1853 – A series of prints depicting the twenty-four generals of the Takeda clan.

- Half-length portrait of Goshaku Somegoro, 1853 – A portrait of the actor Goshaku Somegoro.

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, 1844 – Kuniyoshi’s famous triptych depicting the sorceress Princess Takiyasha summoning a giant skeleton to confront her enemies.

- The mouse turned into a maid, 1847 – A humorous print depicting a mouse transformed into a maid by a sorcerer. Based on an ancient fable of Indian origin.

Examples

Left: Keyamura Rokusuke under the Hikosan Gongen waterfall, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Mouse Turned into a Maid, 1847. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

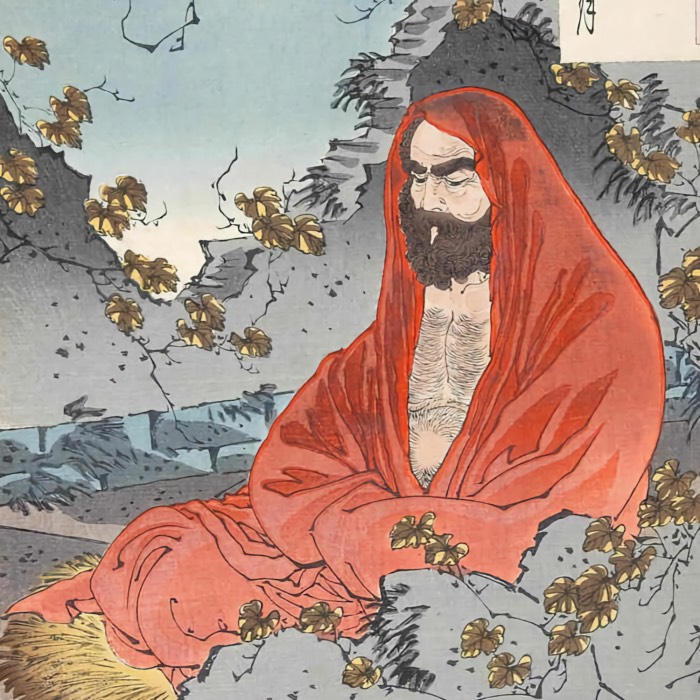

Praying for Rain at Reizen-ga-saki, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren Prays for Rain at the Promontory of Ryozangasaki in Kamakura in 1271. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Praying for Rain at Reizen-ga-saki, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren Prays for Rain at the Promontory of Ryozangasaki in Kamakura in 1271. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Pilgrims in the waterfall. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Pilgrims in the waterfall. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

On the shore of the Sumida River. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

On the shore of the Sumida River. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Mt. Fuji from the Sumida. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Mt. Fuji from the Sumida. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Takeda Nobushige from the series 24 Generals of Kai Province, 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: From the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1840. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: From the series Heroes of Our Country’s Suikoden, 1830. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Hanagami Danjo no jo Arakage fighting a giant salamander, 1834-1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Miyamoto Musashi killing a giant lizard, 1861. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Saito Oniwakamaru, the young Benkei, fights the giant carp at the Bishimon waterfall. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Hatsuhana doing penance under the Tonosawa waterfall, 1841-1842. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Portrait of Chicasei Goyō (Wu Yong) from Water Margin, 1827–1830. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Oda Nobunaga, 1830. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Yoshitsune and Benkei defending themselves in their boat during a storm created by the ghosts of conquered Taira clan warriors, 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Minamoto no Tametomo with a gunsen fan, 1851. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Four cats in different poses illustrating Japanese proverbs, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Acts 5-8 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act five at top right, act six at bottom right, act seven at top left, act eight at bottom left, 1836. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Banishment to Sado Island: Sutra title on the Waves at Kakuta, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren calms a storm at Kakuda. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Banishment to Sado Island: Sutra title on the Waves at Kakuta, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren calms a storm at Kakuda. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Night attack from Chūshingura, 1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Night attack from Chūshingura, 1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kasumigaseki in Edo, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kasumigaseki in Edo, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Foxes Being Trained in Disguise, 1840s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Foxes Being Trained in Disguise, 1840s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: From Three Kingdoms (Huatuo bone scraping Guan Yu arrow treatment). A wound from a poison arrow required the bone to be scraped. Without the use of anesthetic Guan Yu plays go to distract himself from the pain. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Kyumonryu Shinshin and Chokanko Chintasu. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Senkaji Chao wringing out his cloth. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Yan Qing the Graceful (Roshi Ensei) with all his body tattooed is lifting a heavy beam, 1861. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Konseimao Hanzui beset by demons. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Zhu Gui from the series The Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Suikoden. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

In the Snow at Tsukahara, Sado Island, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren walks in the snow on Sado Island. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

In the Snow at Tsukahara, Sado Island, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren walks in the snow on Sado Island. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Tōjō Komatsubara, Eleventh day of Eleventh month, 1264, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Tojo no Saemon Attacks Nichiren at Komatsubara in 1264. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Tōjō Komatsubara, Eleventh day of Eleventh month, 1264, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Tojo no Saemon Attacks Nichiren at Komatsubara in 1264. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Star of Wisdom Descends on the Thirteenth Night of the Ninth Month, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Star of Wisdom Descends on the Thirteenth Night of the Ninth Month, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Converting the Spirit of a Cormorant Fisherman, Isawa River, Kai, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren Praying for the Repose of the Soul of the Cormorant Fisher at the Isawa River in Kai Province. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Converting the Spirit of a Cormorant Fisherman, Isawa River, Kai, from the series Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest, 1835-1836. Nichiren Praying for the Repose of the Soul of the Cormorant Fisher at the Isawa River in Kai Province. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Taishun, from Mirror of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami). Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Taishun, from Mirror of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami). Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

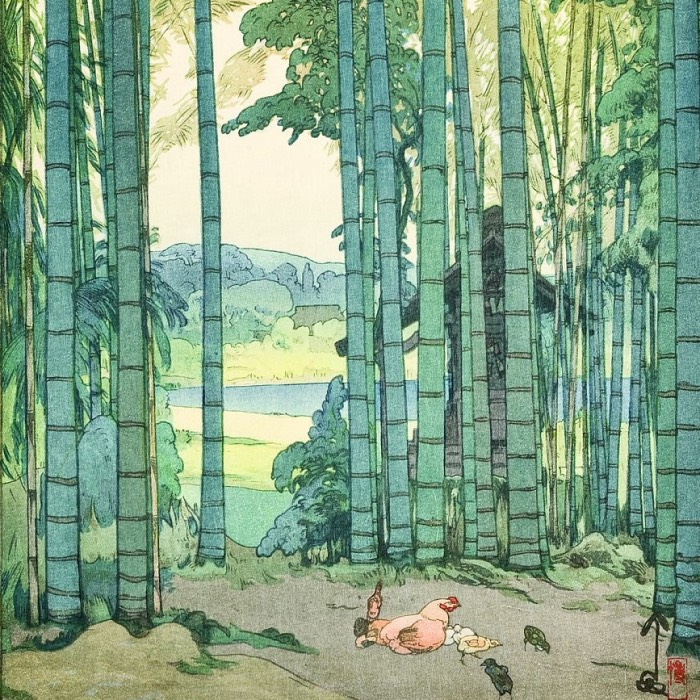

Mōsō, from Mirror of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami). Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Mōsō, from Mirror of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami). Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Kwakkyo, from Mirror of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami). Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Kwakkyo, from Mirror of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (Nijūshi-kō dōji kagami). Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: A Ken Game for Good Fortune in the New Year of the Monkey (Iroma sarutoshi haru no kotobuki ocha no ko ken), 1848. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: Comical Ken Game of Darumas (Dōke Daruma ken), 1847. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: Bizenkō Shutō, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Bizenkō Shutō, an iron truncheon in his mouth, tying his girdle on some steps under a brocade curtain. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: Byōtaichū Setsuei and Shōsharan, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: Hakujisso Hakushō, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Hakujisso Hakushō lifting a box of snakes above a foe with whom he is struggling. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: Hōtenrai (or Kōtenrai) Ryōshin, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Hōtenrai Ryōshin, in armor, discharging a huge cannon, the flaming linstock in his hand. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: Kikenji Tokyō, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: Kimmōken Dankeijū, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: Kinsempyōshi Tōryū, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: Chūsenko Teitokuson, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: Tammeijirō Genshōgo, from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, 1827-1830. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: Noodles from Shinano Province, from Famous Products of Mountain and Sea (Sankai meisan zukushi), c. 1833. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Hodogaya, Totsuka, Fujisawa and Hiratsuka Stations, from Famous Views of the *Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō go-jū-san eki roku shuku meisho), c. 1835. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Hodogaya, Totsuka, Fujisawa and Hiratsuka Stations, from Famous Views of the *Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō go-jū-san eki roku shuku meisho), c. 1835. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Maisaka, Arai, Shirasuka, Futakawa, Yoshida and Goyū Stations, from Famous Views of the *Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō go-jū-san eki roku shuku meisho), c. 1835. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Maisaka, Arai, Shirasuka, Futakawa, Yoshida and Goyū Stations, from Famous Views of the *Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō go-jū-san eki roku shuku meisho), c. 1835. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Mount Fuji off the coast of Tsukuda Island (Tsukuda oki kaisei no Fuji), from Thirty-six Views of Fuji from the Eastern Capital (Tōto Fuji-mi san-jū-rokkei), c. 1843. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Mount Fuji off the coast of Tsukuda Island (Tsukuda oki kaisei no Fuji), from Thirty-six Views of Fuji from the Eastern Capital (Tōto Fuji-mi san-jū-rokkei), c. 1843. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Snow at Benten Shrine and Kinryūzan Temple in Asakusa (Asakusa kinryūzan bentenyama setchû no zu), from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Snow at Benten Shrine and Kinryūzan Temple in Asakusa (Asakusa kinryūzan bentenyama setchû no zu), from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Cherry Blossoms at Tsukiji Temple, from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Cherry Blossoms at Tsukiji Temple, from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Picture of Meguro Fudo Shrine, from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Picture of Meguro Fudo Shrine, from an untitled series of famous places in Edo, 1853. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Ebb tide at Shubi no Matsu (Tōto Shubi no matsu no zu), from The Eastern Capital (Tōto), c. 1833. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Ebb tide at Shubi no Matsu (Tōto Shubi no matsu no zu), from The Eastern Capital (Tōto), c. 1833. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Rain at the man-made gorge of the Kanda River at Ochanomizu in Edo, 1830s. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Rain at the man-made gorge of the Kanda River at Ochanomizu in Edo, 1830s. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Left: The Kobuna-chō Tennō Festival (Kobuna-chō Tennô matsuri), from the Tennō Festival (Tennō matsuri), 1847-1850. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted). – Right: A Brief History of Otake Dainichi Nyorai – The woman who is an incarnation of the Dainichi Buddha (Otake Dainichi Nyorai Ryakuengi), 1849. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

The Transfer Ceremony at Ise Shrine (Ise Daijin miya-utsushi), 1849. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

The Transfer Ceremony at Ise Shrine (Ise Daijin miya-utsushi), 1849. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Great Memorial for Those Killed in the Fires (Shōshi daihōe zu), 1854-1855. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Great Memorial for Those Killed in the Fires (Shōshi daihōe zu), 1854-1855. Source: kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ (license: permission for non-commercial use is granted).

Conclusion

Utagawa Kuniyoshi remains one of the most influential and innovative figures in the history of ukiyo-e and an important figure of the Utagawa School. His dynamic compositions, imaginative subject matter, and ability to navigate the challenges of censorship have earned him a lasting legacy as a master of the genre. I think, that Kuniyoshi’s work continues to inspire artists and captivate audiences with its boldness, creativity, and emotional depth. His contributions to Japanese art, particularly with regard to warrior prints and supernatural imagery, have ensured his place as one of the greats in the ukiyo-e tradition.

References and further reading

- kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ

- Kuniyoshi on ukiyo-e.orgꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Utagawa Kuniyoshiꜛ

- Woldemar von Seidlitz, Dora Amsden, Ukiyo-e, 2016, Parkstone International, ISBN: 9781785257391

- Amy Reigle Newland, The Hotei encyclopedia of Japanese woodblock prints, 2005, Hotei Publishing, ISBN: 9789074822657

- Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing, 2002, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824825539

- Richard Lane, Masters of the Japanese print, their world and their work, 2021, Hassell Street Press, ISBN: 9781015300231

- Andreas Marks, Japanese Woodblock Prints - Artists, Publishers And Masterworks: 1680 - 1900, 2010, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 9784805310557

comments