Utagawa Hiroshige: The poet of landscapes

Among the famous ukiyo-e artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Kuniyoshi, there is another artist from the same period who deserves special attention: Utagawa Hiroshige. Hiroshige was a master of landscape prints, and his works are characterized by their serene beauty and poetic atmosphere. In this post, we briefly explore the life and art of this exceptional artist.

Shōno-juku, from Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, by Hiroshige, c. 1833–34. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Biography

Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川 広重), born Andō Tokutarō in 1797 in Edo (now Tokyo), Japan, is one of the most celebrated ukiyo-e artists, particularly renowned for his evocative and lyrical landscape prints (fūkei-ga). Hiroshige’s work captures the beauty of Japan’s natural scenery and the quiet poetry of everyday life, offering a glimpse into the landscapes, seasons, and culture of the Edo period.

Memorial portrait of Hiroshige by Kunisada, 1858. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Early life and training

Hiroshige was born into a samurai family in the Yayosu barracks in Edo. His father was a fire warden of the Yayosu district, a position of minor samurai rank. As a child, Hiroshige was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps, but he showed an early interest in art, and his talent was recognized at a young age.

At the age of 12, Hiroshige’s parents died, leaving him an orphan. He took over his father’s post as fire warden, but his passion for art persisted. In 1811, at the age of 14, he applied to become a student of Utagawa Toyohiro, a master of the Utagawa School. Toyohiro accepted him, and Hiroshige began his formal training in ukiyo-e.

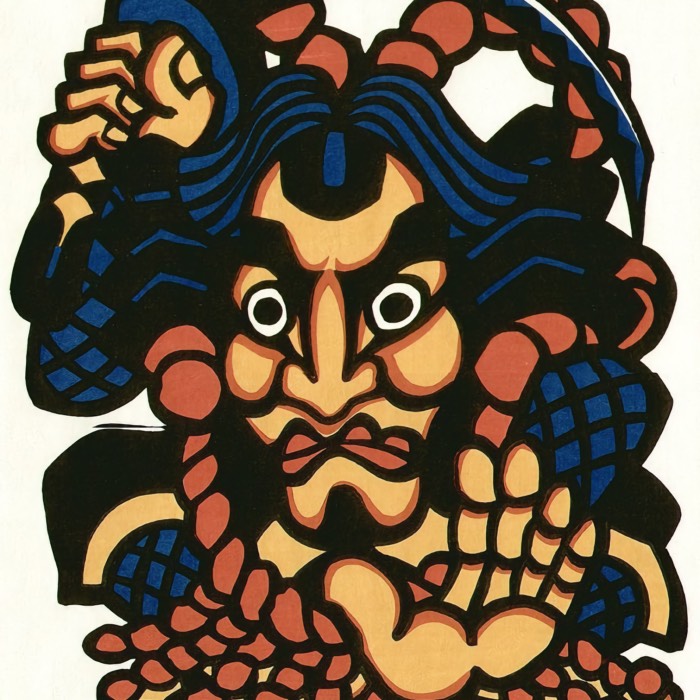

Under Toyohiro’s guidance, Hiroshige learned the techniques of woodblock printing, including drawing, composition, and the use of color. Although his early work consisted of portraits of kabuki actors (yakusha-e) and beautiful women (bijin-ga), Hiroshige soon developed a preference for landscape (fūkei-ga) and nature subjects (kachō-ga). This focus on landscapes would later define his career and distinguish him from other ukiyo-e artists.

Rise to prominence

Hiroshige’s early career was somewhat unremarkable, as he initially struggled to find a niche in the competitive world of ukiyo-e. However, in 1831, he achieved his first major success with the publication of the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi), which depicted scenes along the Tōkaidō, the famous road connecting Edo and Kyoto.

The series was an immediate success and established Hiroshige as a master of landscape art. His ability to capture the changing moods of the landscape, from misty mornings to moonlit nights, resonated with the public and marked the beginning of his rise to prominence. The Tōkaidō series was reprinted multiple times, and Hiroshige became known for his ability to depict the beauty and tranquility of Japan’s natural environment.

Over the next two decades, Hiroshige produced a vast number of landscape series, cementing his reputation as one of the leading ukiyo-e artists of his time. His work was characterized by its lyrical quality, with a focus on the subtleties of light, weather, and season.

Later years and legacy

In the 1850s, as Hiroshige entered the later stages of his career, he continued to produce highly regarded landscape series, including One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo Hyakkei), which remains one of his most celebrated works. This series depicted famous sites in Edo and is considered a masterpiece of ukiyo-e, capturing the essence of Edo’s urban and natural landscapes.

Hiroshige’s final years were marked by a continued dedication to his art, even as the ukiyo-e tradition faced challenges from the introduction of photography and Western art influences. He died in 1858 during a cholera epidemic, leaving behind a legacy that would profoundly influence both Japanese and Western art.

Hiroshige’s work played a crucial role in the Japonisme movement in Europe, where his prints were admired for their composition, use of color, and depiction of nature. Western artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and James McNeill Whistler drew inspiration from Hiroshige’s work, integrating elements of his style into their own.

Style and significance

Master of landscapes

Hiroshige is best known for his landscape prints (fūkei-ga), which are celebrated for their serene beauty and atmospheric effects. His landscapes are not just depictions of scenery; they are poetic expressions of nature, capturing the fleeting moments and subtle changes that define each scene.

Sokokura, from Seven Hot Springs of Hakone, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Sokokura, from Seven Hot Springs of Hakone, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Hiroshige’s compositions are carefully balanced and often include a sense of depth, achieved through the use of perspective and layering of elements. He frequently employed diagonal lines and asymmetry to create a dynamic flow within the image, guiding the viewer’s eye through the scene.

Hiroshige was a master at depicting different weather conditions and times of day. His use of light and shadow, as well as his ability to suggest mist, rain, snow, and moonlight, gives his prints a distinctive mood and atmosphere. These elements contribute to the emotional resonance of his landscapes, inviting viewers to experience the tranquility and beauty of nature.

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake, by Hiroshige, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Hiroshige often included human figures in his landscapes, portraying them as small but integral parts of the natural world. These figures, whether travelers on the road or fishermen by the shore, add a sense of scale and context to the scenes, emphasizing the harmony between people and their environment.

Use of color and line

Hiroshige’s use of color was subtle and refined, often characterized by the use of a limited palette to evoke specific moods. He frequently used shades of blue, green, and brown to depict the natural world, with the introduction of Prussian blue in the 1830s adding depth and vibrancy to his prints.

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge, by Hiroshige, c. 1857–58. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

His line work was delicate and precise, capable of capturing the fine details of a landscape, such as the texture of tree bark or the ripples on water. Hiroshige’s lines are fluid and natural, contributing to the overall harmony of his compositions.

Influence on Western Art

Hiroshige’s impact extended far beyond Japan. In the late 19th century, his prints, along with those of other ukiyo-e masters, were exported to Europe, where they had a profound influence on Western artists. The Japonisme movement, which celebrated Japanese art and aesthetics, was heavily inspired by Hiroshige’s work.

For instance, Vincent van Gogh was deeply influenced by Hiroshige’s use of color and composition. He even created copies of Hiroshige’s prints, incorporating elements of Hiroshige’s style into his own work. Claude Monet, one of the leading figures of Impressionism, admired Hiroshige’s ability to capture the changing light and atmosphere of a scene. Hiroshige’s influence can be seen in Monet’s focus on landscapes and his exploration of color and light. And James McNeill Whistler was another Western artist influenced by Hiroshige, particularly in his use of color harmonies and the integration of figures into landscapes. Whistler’s Nocturnes series reflects the subtle moodiness and atmospheric qualities found in Hiroshige’s prints.

Significance

Hiroshige’s significance lies in his ability to elevate landscape art to new heights, transforming the genre into a form of poetic expression. His work reflects a deep appreciation for the natural world and a sensitivity to the transient beauty of life. Hiroshige’s landscapes are not just representations of physical places; they are meditations on time, nature, and human existence.

His influence on Western art cannot be overstated. Hiroshige helped to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western art traditions, introducing new ways of seeing and depicting the world that resonated with artists across the globe.

Notable works

Throughout his career, Utagawa Hiroshige produced a vast body of work, including some of the most iconic images in Japanese art. Here are some of his most significant print series:

- Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi), 1833-1834 – A series, depicting the fifty-three post stations along the Tōkaidō road, is one of Hiroshige’s most famous works. Each print captures a unique moment along the journey, from bustling towns to serene countryside, showcasing Hiroshige’s mastery of landscape and atmosphere.

- The Eight Views of Ōmi (Ōmi Hakkei), 1834 – A series inspired by the traditional Eight Views of Xiaoxiang in China, this work depicts scenes around Lake Biwa in Ōmi Province. The prints combine elements of landscape and poetry, evoking a sense of nostalgia and contemplation.

- The Fifty-three Stations of the Kiso Kaidō (Kisokaidō Rokujūsan-tsugi), 1835-1838 – Another major series, this work focuses on the Kiso Kaidō, a road that connected Edo to Kyoto through the mountains. The prints highlight the rugged beauty of the Japanese countryside and the lives of the people who traveled the road. This was a collaborative series with Utagawa Kunisada.

- Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanjūrokkei), 1858 – A series of landscape prints featuring Mount Fuji, Japan’s iconic volcano. Hiroshige’s depictions of Mount Fuji capture the mountain in various seasons and weather conditions, showcasing its enduring presence in the Japanese landscape.

- One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo Hyakkei), 1856-1858 – A late masterpiece, this series depicts famous sites in Edo, capturing the beauty and character of the city through the changing seasons. The series is considered a quintessential example of Hiroshige’s ability to blend urban and natural landscapes.

Examples

Returning Sails at Tsukuda, from Eight Views of Edo, , Hiroshige, early-19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Man on Horseback Crossing a Bridge, from the series The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō, by Hiroshige, c. 1836-1837. This is View 28 and Station 27 at Nagakubo-shuku, depicting the Wada Bridge across the Yoda River. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Hakone, from The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, 1833-34. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Hakone, from The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, 1833-34. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

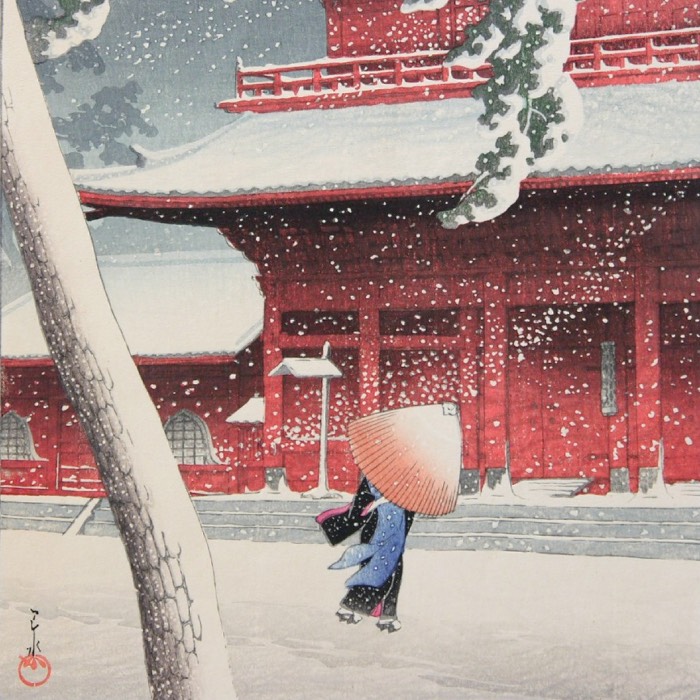

Kanbara, from The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, 1833-34. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kanbara, from The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, 1833-34. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Plum Garden in Kameido (Kameido Umeyashiki), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Futami Bay in Ise Province, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1858. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Sukiyagashi in the Eastern Capital, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1858. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Futamigaura in Ise Province, from hirty-six views of Mount Fuji, 1858. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

View of the Whirlpools at Awa triptych, from the series Snow, Moon and Flowers, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

View of the Whirlpools at Awa triptych, from the series Snow, Moon and Flowers, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

View of Kagurazaka and Ushigome bridge to Edo Castle, 1840. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

View of Kagurazaka and Ushigome bridge to Edo Castle, 1840. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Naruto Whirlpool, Awa Province, from Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces, 1855. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Sumida River, the Wood of the Water god, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1856. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moonlight View of Tsukuda with Lady on a Balcony, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Evening on the Sumida river, 1847-1848. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Moon over Ships Moored at Tsukuda Island from Eitai Bridge, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Kozuke Province, from Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces, 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Horikiri Iris Garden (Horikiri no hanashōbu), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Fudo Falls, Oji, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: View from Massaki of Suijin Shrine, Uchigawa Inlet, and Sekiya, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Yoroi Ferry, Koami-cho, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Heavy rain on a pine tree, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Heavy rain on a pine tree, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Fishing boats on a lake, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Fishing boats on a lake, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

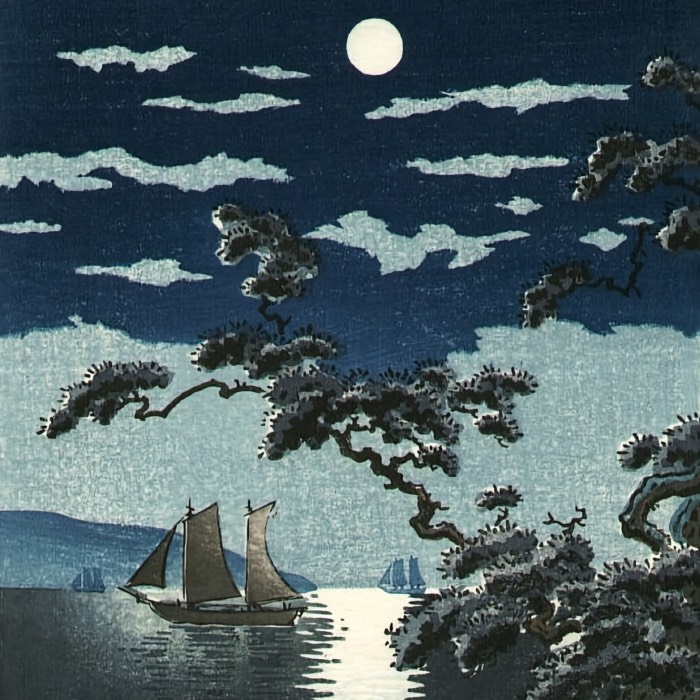

Full moon over a mountain landscape, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Full moon over a mountain landscape, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

View of a long bridge across a lake, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

View of a long bridge across a lake, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

A shrine among trees on a moor. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

A shrine among trees on a moor. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Dragon in clouds, 1830-1839. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Grey mullet and camellia, 1834-1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Grey mullet and camellia, 1834-1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Horse-mackerel and prawns, 1834-1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Horse-mackerel and prawns, 1834-1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Evening Bell, Mii Temple, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Evening Bell, Mii Temple, from Eight Views of Ōmi, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

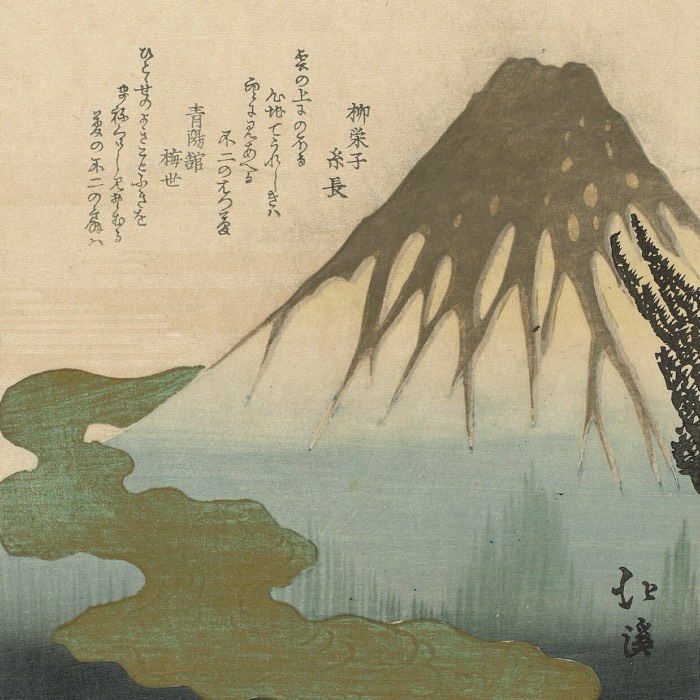

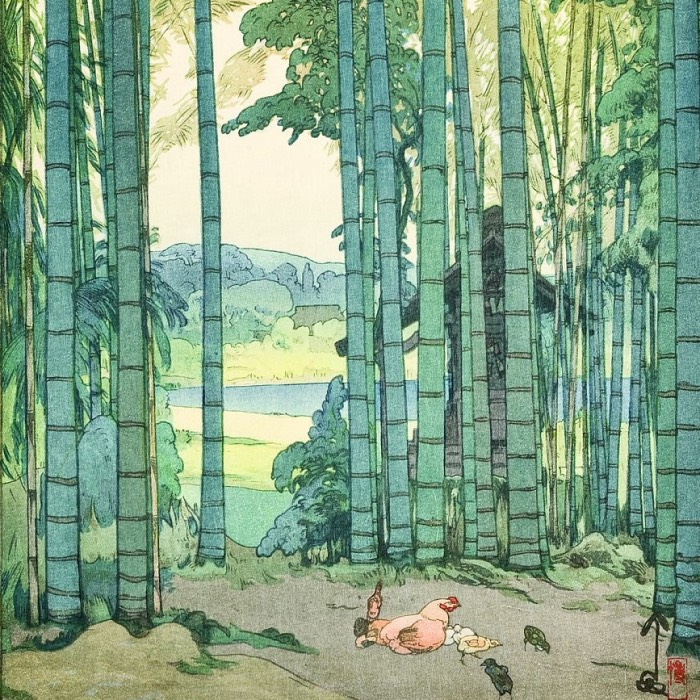

Back View of Mt.Fuji from Dream Mountain in Kai Province (Kai yumeyama urafuji), from *Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Back View of Mt.Fuji from Dream Mountain in Kai Province (Kai yumeyama urafuji), from *Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Valley of Approach at Oyama in Sagami Province (Sagami ōyama raigōdani), from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Valley of Approach at Oyama in Sagami Province (Sagami ōyama raigōdani), from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Mount Fuji seen from Kinegawa, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Mount Fuji seen from Kinegawa, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Sea at Satta, Suruga Province, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1858. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Suruga-chō, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Senzoku pond, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Nihonbashi: Clearing after Snow (Nihonbashi yukibare), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Kasumigaseki, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Ekōin Temple in Ryōgoku and Moto-Yanagi Bridge (Ryōgoku Ekōin Moto-Yanagibashi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Hatsune Riding Ground in Bakuro-chō (Bakuro-chō Hatsune no baba), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Shops with Cotton Goods in Ōdenma-chō (Ōtenma-chō momendana), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Yatsukōji, Inside Sujikai Gate (Sujikai uchi Yatsukōji), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Yatsukōji, Inside Sujikai Gate (Sujikai uchi Yatsukōji), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Kiyomizu Hall and Shinobazu Pond at Ueno (Ueno Kiyomizu-dō Shinobazu no ike, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Ueno Yamashita, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Shitaya Hirokōji, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Temple Gardens in Nippori (Nippori jiin no rinsen), from *One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Suwa Bluff in Nippori (Nippori Suwanodai), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The Ōji Inari Shrine (Ōji Inari no yashiro), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Kawaguchi Ferry and Zenkōji temple (Kawaguchi no watashi Zenkōji), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Mount Atago in Shiba (Shiba Atagoyama), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: New Fuji in Meguro (Meguro Shin-Fuji), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The Original Fuji in Meguro (Meguro Moto-Fuji), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Plum Orchard in Kamada (Kamada no umezono), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moto-Hachiman Shrine in Sunamura (Sunamura Moto-Hachiman), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Towboats Along the Yotsugi-dōri Canal (Yotsugi dōri yōsui hikifune), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Night View of Matsuchiyama and the San’ya Canal (Matsuchiyama San’yabori yakei), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Dawn Inside the Yoshiwara (Kakuchū shinonome), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Cherry Blossoms on the Banks of the Tama River (Tamagawa tsutsumi no hana), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: View of Nihonbashi itchōme Street (Nihonbashi Tōri itchōme ryakuzu), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Yatsumi Bridge (Yatsumi no hashi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Seidō and Kanda River from Shōhei Bridge (Shōheibashi Seidō Kandagawa), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The Pagoda of Zōjōji Temple and Akabane (Zōjōjitō Akabane), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Sumiyoshi Festival at Tsukudajima (Tsukudajima Sumiyoshi no matsuri), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Mitsumata Wakarenofuchi, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Ryōgoku Bridge and the Great Riverbank (Ryōgokubashi Ōkawabata), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The ‘Pine of Success’ and Oumayagashi on the Asakusa River (Asakusagawa shubi no matsu Oumayagashi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: The Ayase River and Kanegafuchi (Ayasegawa Kanegafuchi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The Ferry at Sakasai (Sasakai no watashi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Teppōzu and Tsukiji Monzeki Temple (Teppōzu Tsukiji Monzeki)Teppōzu and Tsukiji Monzeki Temple (鉄砲洲築地門跡, Teppōzu Tsukiji Monzeki. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Moon Viewing (Tsuki no Misaki), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Kinokuni Hill and Distant View of Akasaka and the Tameike Pond (Kinokunizaka Akasaka Tameike enkei), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Night View of Saruwaka (Saruwaka-machi yoru no kei), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: In the Akiba Shrine at Ukeji (Ukechi Akiba no keinai), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: The Maple Trees at Mama, the Tekona Shrine and Tsugihashi Bridge (Mama no momiji Tekona no yashiro Tsugihashi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Fireworks by Ryōgoku Bridge (Ryōgoku hanabi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Kinryūzan Temple in Asakusa (Asakusa Kinryūzan), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival (Asakusa tanbu Torinomachi mōde), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Fukagawa Susaki and Jūmantsubo (Fukagawa Susaki Jūmantsubo), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Minami Shinagawa and Samezu Coast (Minamishinagawa Samezu kaigan), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Meguro Drum Bridge and Sunset Hill (Meguro taikobashi Yūhi no oka), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Atagoshita and Yabu Lane (Atagoshita Yabukōji), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Bikuni Bridge in Snow (Bikunihashi setchū), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Sugatami Bridge, Omokage Bridge and Jariba at Takata (Takata Sugatami no hashi Omokage no hashi Jariba), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: View from the Hilltop of Yushima Tenjin Shrine (Yushima Tenjin sakaue chōbō), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Kitsunebi on New Year’s Night under the Enoki Tree near Ōji (Ōji shōzoku wenoki ōtsugomorihi no kitsunebi), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: View of the Paulownia Imperiales Trees at Akasaka on a Rainy Evening (Akasaka kiribatake uchū yūkei), from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Conclusion

In my opinion, Utagawa Hiroshige remains one of the most beloved and influential figures in the history of ukiyo-e. His landscapes, characterized by their lyrical beauty and atmospheric depth, have left an indelible mark on the ukiyo-e gerne and beyond. Hiroshige’s ability to capture the transient beauty of nature and the quiet poetry of everyday life distinguishes his work, making it resonate with viewers across generations. In a broader context, Hiroshige’s artworks are an expression of an aesthetic sensibility of the universal beauty of the natural world – much like haikus set in color.

References and further reading

- kuniyoshiproject.comꜛ

- Hiroshige on ukiyo-e.orgꜛ

- Woldemar von Seidlitz, Dora Amsden, Ukiyo-e, 2016, Parkstone International, ISBN: 9781785257391

- Amy Reigle Newland, The Hotei encyclopedia of Japanese woodblock prints, 2005, Hotei Publishing, ISBN: 9789074822657

- Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing, 2002, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824825539

- Richard Lane, Masters of the Japanese print, their world and their work, 2021, Hassell Street Press, ISBN: 9781015300231

- Andreas Marks, Japanese Woodblock Prints - Artists, Publishers And Masterworks: 1680 - 1900, 2010, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 9784805310557

comments