Katsushika Hokusai: The visionary of ukiyo-e

I this post, we briefly elucidate the life and work of the iconic Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), known for his groundbreaking contributions to the ukiyo-e genre. Hokusai’s innovative compositions, mastery of color and line, and wide-ranging exploration of subjects have left an indelible mark on the world of art, inspiring generations of artists and art enthusiasts.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa (神奈川沖浪裏, Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura), perhaps the most famous ukiyo-e print by Hokusai, 1831. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Biography

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾 北斎) was born in October 1760 in the Katsushika district of Edo (now Tokyo), Japan. Hokusai is perhaps the most famous ukiyo-e artist, celebrated for his iconic landscapes and his pioneering approach to composition and technique. His career spanned seven decades, during which he produced a vast body of work that continues to influence artists and art movements around the world.

Hokusai’s self-portrait as an old man. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Early life and training

Katsushika Hokusai was born to an artisan family, possibly as the son of a mirror maker named Nakajima Ise. From a young age, Hokusai was exposed to the craft and trade culture of Edo, a bustling urban center known for its vibrant art scene. Hokusai showed an early interest in drawing, and by the age of 14, he had begun his apprenticeship in woodblock carving, a common starting point for many aspiring ukiyo-e artists.

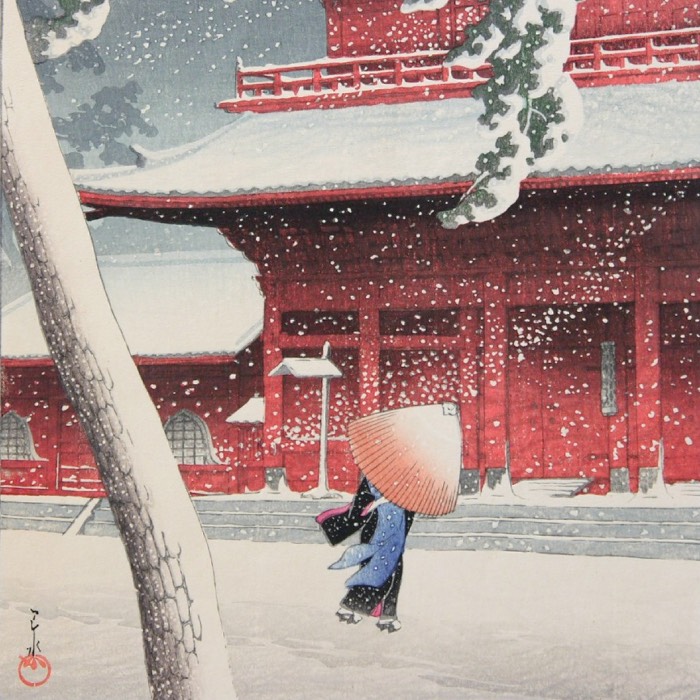

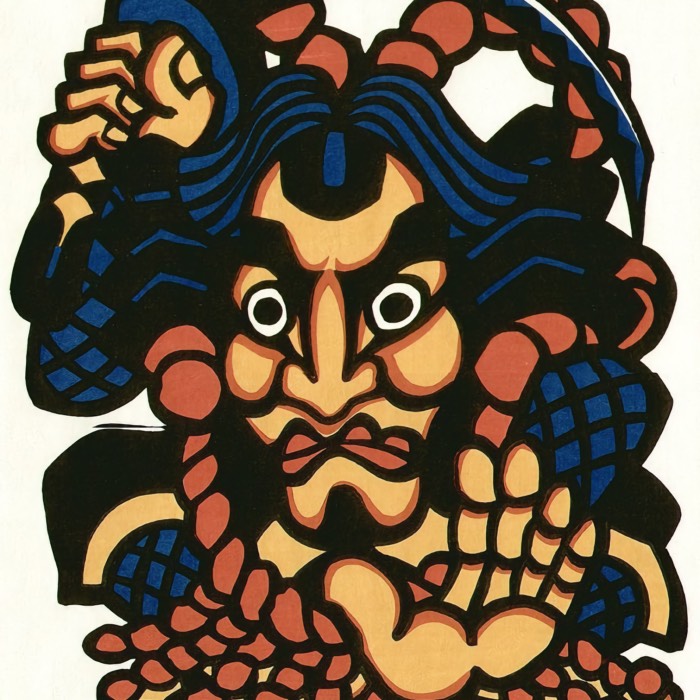

At around 18, Hokusai joined the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō, a prominent artist and founder of the Katsukawa School, known for his work in the ukiyo-e genre, particularly in portraits of kabuki actors (yakusha-e). Under Shunshō’s guidance, Hokusai learned the intricacies of ukiyo-e design, from the delicate art of sketching to the technical demands of preparing woodblocks for printing. It was during this period that he adopted the name “Katsushika Hokusai”, marking the beginning of his long and prolific career.

Hokusai’s early work focused primarily on yakusha-e (actor portraits) and bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women), adhering to the popular styles of the time. However, even in these early works, Hokusai’s unique approach to composition and attention to detail were becoming apparent.

A life of constant reinvention

Hokusai was a restless and highly inventive artist who frequently changed his style, subjects, and even his name. Over the course of his life, he adopted more than 30 different names, each marking a new phase in his artistic development. This habit of reinvention reflected his insatiable curiosity and desire to explore new artistic frontiers.

In the early 1790s, following the death of his master Shunshō, Hokusai began to break away from the Katsukawa School’s traditions. He experimented with Western techniques, such as perspective and shading, which he had encountered through imported European prints and books. These experiments broadened his artistic vocabulary and set the stage for his later masterpieces. In the early 1800s, Hokusai began to establish his own lineage of artists, known as the Hokusai School, which attracted a new generation of students and followers such as Totoya Hokkei.

Hokusai’s life was not without hardship. He faced numerous personal and financial difficulties, including the loss of his wife and children and periods of poverty. Despite these challenges, Hokusai remained fiercely dedicated to his art, often stating that his true artistic achievements were yet to come, even in his later years.

Peak of his career

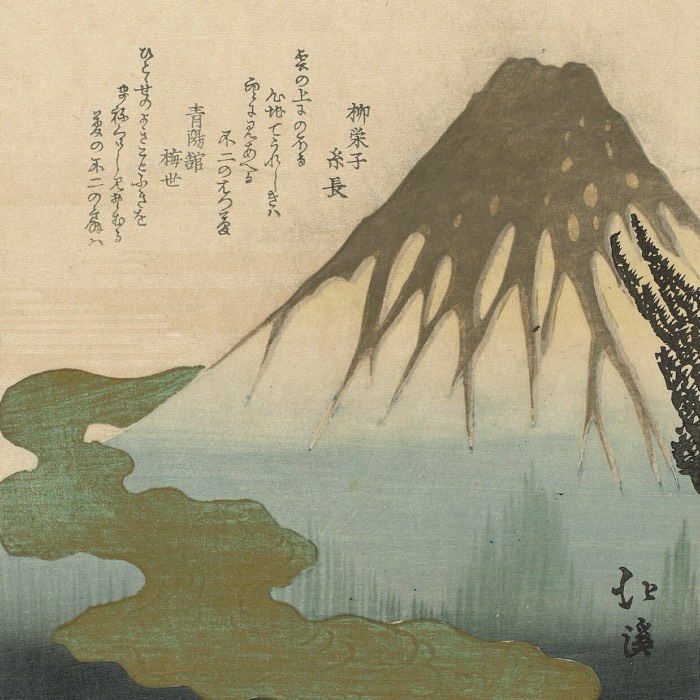

Hokusai reached the pinnacle of his career in the 1820s and 1830s, a period marked by the creation of some of his most famous works. It was during this time that he produced the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanjūroku-kei), which includes the iconic print The Great Wave off Kanagawa. This series not only solidified Hokusai’s reputation as a master of landscape art but also introduced the concept of the meisho-e (famous place print), focusing on well-known locations and natural landmarks.

Fukagawa Mannen-bashi shita (Under Mannen Bridge at Fukagawa), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Fukagawa Mannen-bashi shita (Under Mannen Bridge at Fukagawa), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

This period also saw the publication of Hokusai’s Hokusai Manga, a collection of sketchbooks that covered a wide range of subjects, from landscapes and animals to people and mythological creatures. The Manga became a major source of inspiration for both Japanese and Western artists, offering a comprehensive visual record of Hokusai’s creative genius.

Example pages from the Hokusai Manga, 1814. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example pages from the Hokusai Manga, 1814. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Hokusai’s fascination with Mount Fuji is evident in much of his work, and it reflects the cultural and spiritual significance of the mountain in Japanese society. His depictions of Fuji, seen from different perspectives and in various conditions, showcase his innovative use of color, composition, and line, which brought a new dynamism to ukiyo-e.

Later years and legacy

Even in his later years, Hokusai continued to work tirelessly, producing some of his most innovative and experimental works. His commitment to his craft was legendary; he is said to have proclaimed on his deathbed that if only he had more time, he would have become a true artist.

Hokusai’s influence extended beyond Japan, particularly during the Japonisme movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His works were among the first Japanese prints to be widely exported to Europe, where they profoundly influenced Western artists, including Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and Paul Gauguin. His mastery of composition, use of bold lines, and exploration of new perspectives left an indelible mark on the development of modern art.

Katsushika Hokusai died in May 1849 at the age of 88. He left behind a legacy as one of Japan’s greatest artists, whose work bridged the gap between traditional Japanese art and the emerging modern aesthetics of the 19th century.

Style and significance

Innovative use of composition

Hokusai was a pioneer in the use of composition in ukiyo-e. He often employed bold, unconventional perspectives, such as extreme close-ups and bird’s-eye views, to create dynamic and engaging images. His compositions broke away from the traditional, often symmetrical layouts of earlier ukiyo-e artists, introducing a sense of movement and depth that was both striking and novel.

Perhaps the most famous example of Hokusai’s innovative composition, The Great Wave off Kanagawa (神奈川沖浪裏, Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura) print depicts a towering wave about to crash down on three small boats, with Mount Fuji visible in the distance. The juxtaposition of the immense wave and the distant, serene mountain creates a powerful visual tension that has captivated viewers for generations.

Mastery of color and line

Hokusai’s use of color was both bold and nuanced. He was known for his ability to create depth and atmosphere through careful gradations of color and the use of different printing techniques. His works often featured a limited but striking color palette, with a particular emphasis on blues and greens, which became more vibrant with the introduction of Prussian blue pigment to Japan.

Edo Nihon-bashi, (Nihonbashi bridge in Edo), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Edo Nihon-bashi, (Nihonbashi bridge in Edo), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

His use of line was equally masterful. Hokusai’s lines were fluid and expressive, capable of conveying a wide range of textures and forms, from the delicate curves of a woman’s hair to the rough, jagged edges of a mountain. This combination of precise line work and vibrant color gave his prints a dynamic quality that set them apart from those of his contemporaries.

Exploration of a wide range of subjects

Hokusai’s work spanned a vast array of subjects, reflecting his insatiable curiosity and love for the natural world. His prints and paintings include:

- Landscapes (fūkei-ga, meisho-e): Hokusai is best known for his landscape prints, particularly those featuring Mount Fuji. His landscapes often depict scenes of everyday life set against the backdrop of Japan’s natural beauty, capturing the harmonious relationship between people and their environment.

- Nature and animals (kachō-ga): Hokusai had a deep appreciation for the natural world, which is evident in his detailed studies of animals, birds, and plants. His ability to capture the essence of his subjects with a few simple lines is a testament to his observational skills and artistic talent.

- Human figures and daily life (e.g., ōkubi-e): Hokusai’s prints frequently depicted scenes from daily life, including farmers working in fields, travelers on the road, and urban dwellers going about their business. These images offer a glimpse into the lives of ordinary people in Edo-period Japan.

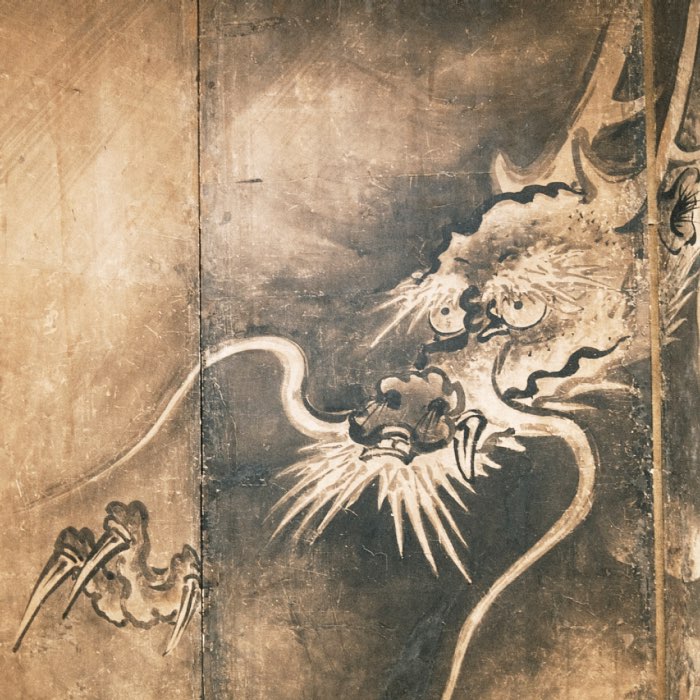

- Mythological and supernatural themes (yūrei-zu): Hokusai also explored themes from Japanese folklore and mythology, creating prints that featured gods, demons, and legendary heroes. His imaginative depictions of supernatural beings reveal his fascination with the mystical and the unknown.

- Erotica art (shunga): Hokusai was also known for his shunga prints, which depicted erotic scenes with humor and sensuality. These works were popular among Edo-period audiences and were often exchanged as gifts or kept as private collections.

Notable works

Katsushika Hokusai produced an extensive body of work throughout his lifetime, including some of the most iconic images in Japanese art. Below are a few of his most significant works:

- Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing (Ehon Ryakuga hayaoshie), 1812 – A series of instructional books on drawing and painting, featuring Hokusai’s distinctive style and approach to art.

- Hokusai Manga, first published in 1814 – A collection of sketches covering a wide range of subjects, from landscapes and animals to people and mythical creatures. The Manga served as a source of inspiration for both Japanese and Western artists.

- The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (Tako to Ama, Octopus(es) and the Shell Diver), first published in 1814 – A famous shunga print depicting an erotic encounter with an octopus, included in Kinoe no Komatsu, a three-volume book of shunga erotica.

- Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanjūrokkei), 1830 to 1832 – A series of landscape prints featuring Mount Fuji in various settings and seasons. Among the most famous prints in the series are:

- The Great Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura) – An iconic image of a towering wave about to crash down on three small boats, with Mount Fuji visible in the distance.

- Red Fuji (Akafuji) – A striking image of Mount Fuji tinged with red light at sunset.

- South Wind, Clear Sky (Gaifū kaisei) – A serene landscape featuring Mount Fuji under a clear blue sky.

- 108 Heroes of the Suikoden (Tsūzoku Suikoden gōketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori), 1827-1830 – A series of prints based on the Chinese novel Water Margin, featuring 108 heroic bandits and warriors.

- A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces (Shokoku taki meguri), 1833 – A series of prints depicting famous waterfalls from across Japan, showcasing Hokusai’s skill in capturing the power and beauty of nature.

- Oceans of Wisdom (Chie no umi), 1832-1834 – A series of ten fishing-themed prints.

- One Hundred Ghost Tales (Hyaku monogatari), 1833 – A series of prints depicting supernatural beings and ghost stories (yūrei-zu).

- Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges, 1834 – A series of prints featuring famous bridges from across Japan.

- One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku hyakkei), 1834-1835 – A series of landscape prints featuring Mount Fuji in various settings and moods.

Examples

Kajikazawa in Kai Province, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, by Hokusai, forst publication: 1830; this edition: circa 1930. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Tenma Bridge in Setsu Province, from Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges, by Hokusai. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Shunga example: The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, by Hokusai, 1814. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Amida Falls, from A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls, by Hokusai, 1829-33. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Gaifū kaisei (Fine Wind, Clear Morning), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Gaifū kaisei (Fine Wind, Clear Morning), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Fireworks in the Cool of Evening at Ryogoku Bridge in Edo, c. 1788–89. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Fireworks in the Cool of Evening at Ryogoku Bridge in Edo, c. 1788–89. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kirifuri waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke, from A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls, 1831-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kirifuri waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke, from A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls, 1831-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Cuckoo and Azaleas, 1834 from the Small Flower series, 1828. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Cuckoo and Azaleas, 1834 from the Small Flower series, 1828. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Ghost of Oiwa, from One Hundred Ghost Stories, 1826. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Ghost of Oiwa, from One Hundred Ghost Stories, 1826. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Chōshi in Shimosha, from Oceans of Wisdom, 1833. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Chōshi in Shimosha, from Oceans of Wisdom, 1833. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Fuji Seen from Kanaya on the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō Kanaya no Fuji), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Fuji Seen from Kanaya on the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō Kanaya no Fuji), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

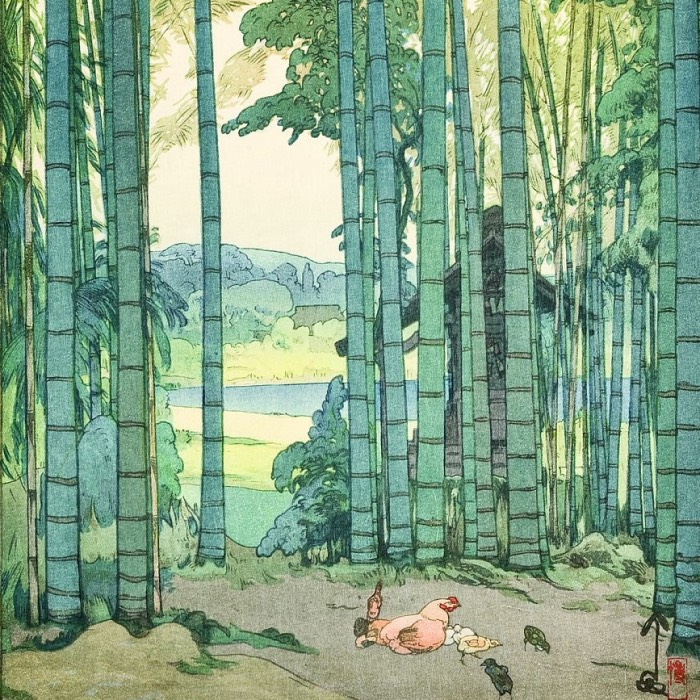

Lake Suwa in Shinano Province (Shinshū Suwako), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Lake Suwa in Shinano Province (Shinshū Suwako), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Bishū Fujimigahara (Fuji viewed from rice fields in Owari Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Bishū Fujimigahara (Fuji viewed from rice fields in Owari Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sunshū Ejiri (Ejiri in Suruga Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sunshū Ejiri (Ejiri in Suruga Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Honjo Tatekawa (The timberyard at Honjo), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Honjo Tatekawa (The timberyard at Honjo), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

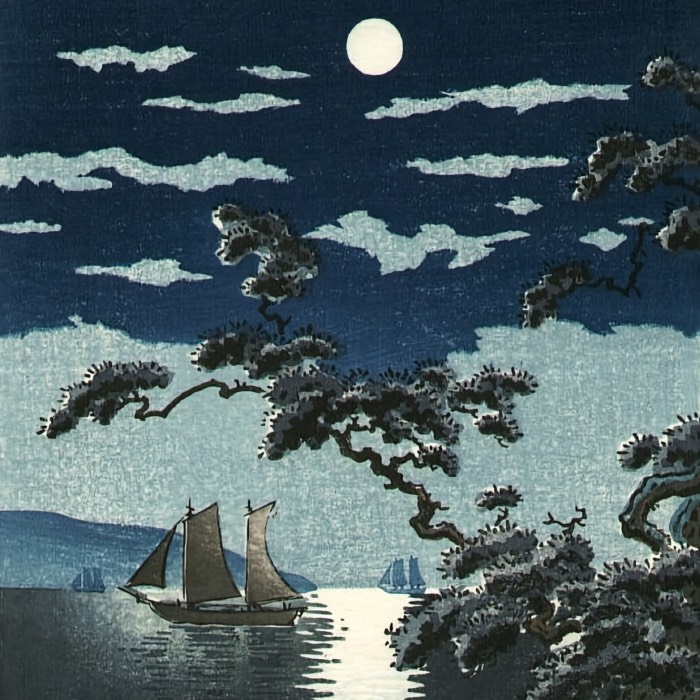

Jōshū Ushibori (Ushibori in Hitachi Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Jōshū Ushibori (Ushibori in Hitachi Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1830. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sarayashiki (A woman ghost appeared from a well), 1831. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sarayashiki (A woman ghost appeared from a well), 1831. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Peonies and Canary, 1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Peonies and Canary, 1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Aoyama Enza-no-matsu (The Cushion Pine at Aoyama), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Aoyama Enza-no-matsu (The Cushion Pine at Aoyama), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kōshū Inume-tōge (Inume Pass in Kai Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kōshū Inume-tōge (Inume Pass in Kai Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kōto Suruga-cho Mitsui-mise ryakuzu (A sketch of the Mitsui shop in Suruga in Edo), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kōto Suruga-cho Mitsui-mise ryakuzu (A sketch of the Mitsui shop in Suruga in Edo), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Ommayagashi yori ryōgoku-bashi yūhi mi (Sunset across the Ryōgoku bridge from the bank of the Sumida River at Onmayagashi), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Ommayagashi yori ryōgoku-bashi yūhi mi (Sunset across the Ryōgoku bridge from the bank of the Sumida River at Onmayagashi), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Koishikawa yuki no ashita (Tea house at Koishikawa. The morning after a snowfall), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Koishikawa yuki no ashita (Tea house at Koishikawa. The morning after a snowfall), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Gohyaku-rakanji Sazaidō (Sazai hall – Temple of Five Hundred Rakan), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Gohyaku-rakanji Sazaidō (Sazai hall – Temple of Five Hundred Rakan), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Onden no suisha, (Watermill at Onden), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Onden no suisha, (Watermill at Onden), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Tōkaidō Ejiri tago-no-uraryakuzu (Shore of Tago Bay, Ejiri at Tōkaidō), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Tōkaidō Ejiri tago-no-uraryakuzu (Shore of Tago Bay, Ejiri at Tōkaidō), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Soshū Enoshima, (Enoshima in Sagami Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Soshū Enoshima, (Enoshima in Sagami Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kazusa no kairo (The Kazusa Province sea route), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Kazusa no kairo (The Kazusa Province sea route), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Noboto-ura (Bay of Noboto), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Noboto-ura (Bay of Noboto), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Shinshū Suwa-ko (Mount Fuji Across Lake Suwa), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Shinshū Suwa-ko (Mount Fuji Across Lake Suwa), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sunshū Ōno-shinden (Ōno Shinden in Suruga Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sunshū Ōno-shinden (Ōno Shinden in Suruga Province), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Minobu-gawa ura Fuji (The back of Fuji from the Minobu river), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Minobu-gawa ura Fuji (The back of Fuji from the Minobu river), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-1832. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Miyatogawa nagawa (Fishing in the Miyato River), from the series Oceans of wisdom, 1832-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Miyatogawa nagawa (Fishing in the Miyato River), from the series Oceans of wisdom, 1832-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Machi-ami (Waiting Nets), from the series Oceans of wisdom, 1832-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Machi-ami (Waiting Nets), from the series Oceans of wisdom, 1832-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Washū Yoshino Yoshitsune uma arai no taki (The Waterfall Where Yoshitsune Washed His Horse at Yoshino in Yamato Province), from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, 1833-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Washū Yoshino Yoshitsune uma arai no taki (The Waterfall Where Yoshitsune Washed His Horse at Yoshino in Yamato Province), from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, 1833-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Mino no Yōrō no taki (Yōrō Waterfall in Mino Province), from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, 1833-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Mino no Yōrō no taki (Yōrō Waterfall in Mino Province), from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, 1833-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Toto Aoigaoka no taki (Aoigaoka Falls in the Eastern Capital), from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, 1833-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Toto Aoigaoka no taki (Aoigaoka Falls in the Eastern Capital), from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, 1833-1834. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Poppies Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Poppies Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Egrets from Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing, 1823. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Egrets from Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing, 1823. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Happo Nirami Hoozu, ceiling of Ganshoin temple at Obuse, wall painting. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Happo Nirami Hoozu, ceiling of Ganshoin temple at Obuse, wall painting. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Hawk on a ceremonial stand, ink on paper. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Hawk on a ceremonial stand, ink on paper. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Portrait of chino Hyogo seated at his writing desk, ink on paper. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Portrait of chino Hyogo seated at his writing desk, ink on paper. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Tanuki tea kettle, c. 1840s, ink on paper. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Example of Hokusai’s other (non-ukiyo-e) work: Tanuki tea kettle, c. 1840s, ink on paper. Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Conclusion

Katsushika Hokusai remains a towering figure in the world of ukiyo-e and beyond, known for his innovative compositions, mastery of color and line, and wide-ranging exploration of subjects. His works have not only left a lasting impact on Japanese art but have also influenced countless artists and movements around the world. Hokusai’s legacy endures through his iconic images, which continue to captivate and inspire generations of art lovers and creators. In my opinion, Hokusai’s work and significance can’t be overstated, and his contributions to the art world are truly remarkable, making him a visionary of his time and beyond.

A great source to explore Hokusai’s work are the hokusai-katsushika.orgꜛ and ukiyo-e.orgꜛ websites, which offer a vast collection of his prints.

References and further reading

- Hokusai on ukiyo-e.orgꜛ

- hokusai-katsushika.orgꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Hokusaiꜛ

- Woldemar von Seidlitz, Dora Amsden, Ukiyo-e, 2016, Parkstone International, ISBN: 9781785257391

- Amy Reigle Newland, The Hotei encyclopedia of Japanese woodblock prints, 2005, Hotei Publishing, ISBN: 9789074822657

- Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing, 2002, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824825539

- Richard Lane, Masters of the Japanese print, their world and their work, 2021, Hassell Street Press, ISBN: 9781015300231

- Andreas Marks, Japanese Woodblock Prints - Artists, Publishers And Masterworks: 1680 - 1900, 2010, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 9784805310557

comments